Once more was the ground covered with snow to the depth

of three feet. The cattle were littered down inside the enclosure of

palisades round the cow-house; the sheep were driven into the inclosed

sheep-fold, and the horses were put into a portion of the barn in the

sheep-fold which had been parted off for them. All was made secure, and

every preparation made for the long winter. Although there had been a

fall of snow, the severe frost had not yet come on. It did, however, in

about a fortnight afterwards, and then, according to the wishes of the

Colonel, six oxen were killed for the use of the fort, and taken there

by the horses on a sledge; this was the last task that they had to

fulfil, and then Alfred bade adieu to the officers of the fort, as they

did not expect to meet again till the winter was over. Having

experienced one winter, they were more fully prepared for the second;

and as Malachi, the Strawberry, and John were now regular inmates of the

house (for they did not keep a separate table), there was a greater

feeling of security, and the monotony and dreariness were not so great

as in the preceding winter; moreover, everything was now in its place,

and they had more to attend to—two circumstances which greatly

contributed to relieve the ennui arising

from continual confinement. The hunting-parties went out as usual; only

Henry, and occasionally Alfred, remained at home to attend to the stock,

and to perform other offices which the increase of their establishment

required. The new books brought by Henry from Montreal, and which by

common consent had been laid aside for the winter evenings, were now a

great source of amusement, as Mr Campbell read aloud a portion of them

every evening. Time passed away quickly, as it always does when there is

a regular routine of duties and employment, and Christmas came before

they were aware of its approach.

It

was a great comfort to Mrs Campbell that she now always had John at

home, except when he was out hunting, and on that score she had long

dismissed all anxiety, as she had full confidence in Malachi; but

latterly Malachi and John seldom went out alone—indeed, the old man

appeared to like being in company, and his misanthropy had entirely

disappeared. He now invariably spent his evenings with the family

assembled round the kitchen fire, and had become much more fond of

hearing his own voice. John did not so much admire these evening

parties. He cared nothing for new books, or indeed any books. He would

amuse himself making mocassins, or working porcupine-quills with the

Strawberry at one corner of the fire, and the others might talk or read,

it was all the same, John never said a word, or appeared to pay the

least attention to what was said. His father occasionally tried to make

him learn something, but it was useless. He would remain for hours with

his book before him, but his mind was elsewhere. Mr Campbell, therefore,

gave up the attempt for the present, indulging the hope that when John

was older he would be more aware of the advantages of education, and

would become more attentive. At present, it was only inflicting pain on

the boy without any advantage being gained. But John did not always sit

by the kitchen fire. The wolves were much more numerous than in the

preceding winter, having been attracted by the sheep which were within

the palisade, and every night the howling was incessant. The howl of a

wolf was sufficient to make John seize his rifle and leave the house,

and he would remain in the snow for hours till one came sufficiently

near for him to fire at, and he had already killed several when a

circumstance occurred which was the cause of great uneasiness.

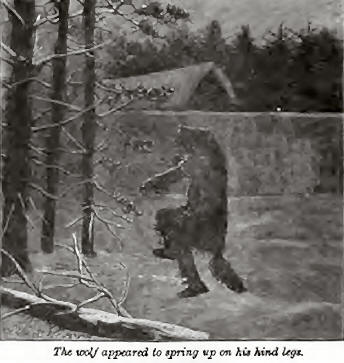

John was out one evening as usual, crouched down within the palisades,

and watching for the wolves. It was a bright starry night, but there was

no moon, when he perceived one of the animals crawling along almost on

its belly, close to the door of the palisade which surrounded the house.

This surprised him, as, generally speaking, the animals prowled round

the palisade which encircled the sheep-fold, or else close to the

pigsties which were at the opposite side from the entrance door. John

levelled his rifle and fired, when, to his astonishment, the wolf

appeared to spring up on his hind legs, then fall down and roll away.

The key of the palisade door was always kept within, and John determined

to go in and fetch it, that he might ascertain whether he had killed the

animal or not. When he entered Malachi said, “Did you kill, my boy?”

“Don’t know,” replied John; “come for the key to see.”

“I

don’t like the gate being opened at night, John,” said Mr Campbell; “why

don’t you leave it, as you usually do, till to-morrow morning; that will

be time enough?”

“I

don’t know if it was a wolf,” replied John.

“What, then, boy? tell me,” said Malachi.

“Well, I think it was an Indian,” replied John; who then explained what

had passed.

“Well, I shouldn’t wonder,” replied Malachi; “at all events the gate

must not be opened to-night, for if it was an Indian you fired at, there

is more than one of them; we’ll keep all fast, John, and see what it was

to-morrow.”

Mrs Campbell and the girls were much alarmed at this event, and it was

with difficulty that they were persuaded to retire to rest.

“We will keep watch to-night at all events,” said Malachi, as soon as

Mrs Campbell and her nieces had left the room.

“The boy is right, I have no doubt. It is the Angry Snake and his party

who are prowling about, but if the boy has hit the Indian, which I have

no doubt of, they will make off; however, it will be just as well to be

on our guard, nevertheless. Martin can watch here, and I will watch in

the fold.”

We

have before observed that the lodge of Malachi, Martin, and his wife,

was built within the palisade of the sheep-fold, and that there was a

passage from the palisade round the house to that which surrounded the

sheep-fold, which passage had also a palisade on each side of it.

“I

will watch here,” said Alfred; “let Martin go home with you and his

wife.”

“I

will watch with you,” said John.

“Well, perhaps that will be better,” said Malachi; “two rifles are

better than one, and if any assistance is required there will be one to

send for it.”

“But what do you think they would do, Malachi?” said Mr Campbell; “they

cannot climb the palisades.”

“Not well, sir, nor do I think they would attempt it unless they had a

large force, which I am sure they have not; no, sir, they would rather

endeavour to set fire to the house if they could, but that’s not so

easy; one thing is certain, that the Snake will try all he can to get

possession of what he saw in your store-house.”

“That I do not doubt,” said Alfred; “but he will not find it quite so

easy a matter.”

“They’ve been reconnoitring, sir, that’s the truth of it, and if John

has helped one of them to a bit of lead, it will do good; for it will

prove to them that we are on the alert, and make them careful how they

come near the house again.”

After a few minutes’ more conversation, Mr Campbell, Henry, and Percival

retired, leaving the others to watch. Alfred walked home with Malachi

and his party to see if all was right at the sheep-fold, and then

returned.

The night passed without any further disturbance except the howling of

the wolves, to which they were accustomed.

The next morning, at daybreak, Malachi and Martin came to the house,

and, with John and Alfred, they opened the palisade gate, and went out

to survey the spot where John had fired.

“Yes, sir,” said Malachi; “it was an Indian, no doubt of it; here are

the dents made in the snow by his knees as he crawled along, and John

has hit him, for here is the blood. Let’s follow the trail. See, sir, he

has been hard hit; there is more blood this way as we go on. Ha!”

continued Malachi, as he passed by a mound of snow, “here’s the

wolf-skin he was covered up with; then he is dead or thereabouts, and

they have carried him off, for he never would have parted with his skin,

if he had had his senses about him.”

“Yes,” observed Martin, “his wound was mortal, that’s certain.”

They pursued the track till they arrived at the forest, and then,

satisfied by the marks on the snow that the wounded man had been carried

away, they returned to the house, when they found the rest of the family

dressed and in the kitchen. Alfred shewed them the skin of the wolf, and

informed them of what they had discovered.

“I

am grieved that blood has been shed,” observed Mrs Campbell; “I wish it

had not happened. I have heard that the Indians never forgive on such

occasions.”

“Why, ma’am, they are very revengeful, that’s certain, but still they

won’t like to risk too much. This has been a lesson to them. I only wish

it had been the Angry Snake himself who was settled, as then we should

have no more trouble or anxiety about them.”

“Perhaps it may be,” said Alfred.

“No, sir, that’s not likely; it’s one of his young men; I know the

Indian customs well.”

It

was some time before the alarm occasioned by this event subsided in the

mind of Mrs Campbell and her nieces; Mr Campbell also thought much about

it, and betrayed occasional anxiety. The parties went out hunting as

before, but those at home now felt anxious till their return from the

chase. Time, however, and not hearing anything more of the Indians,

gradually revived their courage, and before the winter was half over

they thought little about it. Indeed, it had been ascertained by Malachi

from another band of Indians which he fell in with near a small lake

where they were trapping beaver, that the Angry Snake was not in that

part of the country, but had gone with his band to the westward at the

commencement of the new year. This satisfied them that the enemy had

left immediately after the attempt which he had made to reconnoitre the

premises.

The hunting-parties, therefore, as we said, continued as before; indeed,

they were necessary for the supply of so many mouths. Percival, who had

grown very much since his residence in Canada, was very anxious to be

permitted to join them, which he never had been during the former

winter. This was very natural. He saw his younger brother go out almost

daily, and seldom return without having been successful; indeed, John

was, next to Malachi, the best shot of the party. It was, therefore,

very annoying to Percival that he should always be detained at home

doing all the drudgery of the house, such as feeding the pigs, cleaning

knives, and other menial work, while his younger brother was doing the

duty of a man. To Percival’s repeated entreaties, objections were

constantly raised by his mother; they could not spare him, he was not

accustomed to walk in snow-shoes.

Mr

Campbell observed that Percival became dissatisfied and unhappy, and

Alfred took his part and pleaded for him. Alfred observed very truly

that the Strawberry could occasionally do Percival’s work, and that if

it could be avoided, he should not be cooped up at home in the way that

he was; and, Mr Campbell agreeing with Alfred, Mrs Campbell very

reluctantly gave her consent to his occasionally going out.

“Why, aunt, have you such an objection to Percival going out with the

hunters?” said Mary. “It must be very trying to him to be always

detained at home.”

“I

feel the truth of what you say, my dear Mary,” said Mrs Campbell, “and I

assure you it is not out of selfishness, or because we shall have more

work to do, that I wish him to remain with us; but I have an instinctive

dread that some accident will happen to him, which I cannot overcome,

and there is no arguing with a mother’s fears and a mother’s love.”

“You were quite as uneasy, my dear aunt, when John first went out; you

were continually in alarm about him, but now you are perfectly at ease,”

replied Emma.

“Very true,” said Mrs Campbell; “it is, perhaps, a weakness on my part

which I ought to get over; but we are all liable to such feelings. I

trust in God there is no real cause for apprehension, and that my

reluctance is a mere weakness and folly. But I see the poor boy has long

pined at being kept at home; for nothing is more irksome to a

high-couraged and spirited boy as he is. I have, therefore, given my

consent, because I think it is my duty; still the feeling remains, so

let us say no more about it, my dear girls, for the subject is painful

to me.”

“My dear aunt, did you not say that you would talk to Strawberry on the

subject of religion, and try if you could not persuade her to become a

Christian? She is very serious at prayers, I observe; and appears, now

that she understands English, to be very attentive to what is said.”

“Yes, my dear Emma, it is my intention so to do very soon, but I do not

like to be in too great a hurry. A mere conforming to the usages of our

religion would be of little avail, and I fear that too many of our good

missionaries, in their anxiety to make converts, do not sufficiently

consider this point. Religion must proceed from conviction, and be

seated in the heart; the heart, indeed, must be changed, not mere

outward form attended to.”

“What is the religion of the Indians, my dear aunt?” said Mary.

“One which makes conversion the more difficult. It is in many respects

so near what is right, that Indians do not easily perceive the necessity

of change. They believe in one God, the Fountain of all good; they

believe in a future state and in future rewards and punishments. You

perceive they have the same foundation as we have, although they know

not Christ; and, having very incomplete notions of duty, have a very

insufficient sense of their manifold transgressions and offences in

God’s sight, and consequently have no idea of the necessity of a

mediator. Now it is, perhaps, easier to convince those who are entirely

wrong, such as worship idols and false gods, than those who approach so

nearly to the truth. But I have had many hours of reflection upon the

proper course to pursue, and I do intend to have some conversation with

her on the subject in a very short time. I have delayed because I

consider it absolutely necessary that she should be perfectly aware of

what I say before I try to alter her belief. Now, the Indian language,

although quite sufficient for Indian wants, is poor, and has not the

same copiousness as ours, because they do not require the words to

explain what we term abstract ideas. It is, therefore, impossible to

explain the mysteries of our holy religion to one who does not well

understand our language. I think, however, that the Strawberry now

begins to comprehend sufficiently for me to make the first attempt. I

say first attempt, because I have no idea of making a convert in a week,

or a month, or even in six months. All I can do is to exert my best

abilities, and then trust to God, who, in His own good time, will

enlighten her mind to receive His truth.”

The next day the hunting party went out, and Percival, to his great

delight, was permitted to accompany it. As they had a long way to go—for

they had selected the hunting ground—they set off early in the morning,

before daylight, Mr Campbell having particularly requested that they

would not return home late.