Alfred and Martin brought in the wolf which Emma had

killed, but it was frozen so hard, that they could not skin it. Poor

little Trim was also carried in, but the ground was too hard frozen for

them to bury the body, so they put it into the snow until the spring,

when a thaw would take place. As for the wolf, they said nothing about

it, but they remained up when the rest of the family retired, and after

the wolf had been some time before the fire, they were able to take off

the skin.

On

the following morning, when the hunters went out, they were particularly

desired to shoot a wild turkey if they could, as the next day was

Christmas-day.

On

the following morning, when the hunters went out, they were particularly

desired to shoot a wild turkey if they could, as the next day was

Christmas-day.

“Let us take Oscar with us,” said Alfred; “he is very swift, and may run

them down; we never can get up with them in our snow-shoes.”

“I

wonder whether they will get a turkey,” said Emma, after the hunting

party had left.

“I

think it will be difficult,” said Mrs Campbell; “but they will try all

they can.”

“I

hope they will; for Christmas-day without a turkey will be very

un-English.”

“We are not in England, my dear Emma,” said Mr Campbell; “and wild

turkeys are not to be ordered from the poulterer’s.”

“I

know that we are not in England, my dear uncle, and I feel it too. How

was the day before every Christmas-day spent at Wexton Hall! What piles

of warm blankets, what a quantity of duffel cloaks, flannels, and

worsted stockings were we all so busy and so happy in preparing and

sorting to give away on the following morning, that all within miles of

us should be warmly clothed on that day. And, then, the housekeeper’s

room with all the joints of meat, and flour and plums and suet, in

proportion to the number of each family, all laid out and ticketed ready

for distribution. And then the party invited to the servants’ hall, and

the great dinner, and the new clothing for the school-girls, and the

church so gay with their new dresses in the aisles, and the holly and

the mistletoe. I know we are not in England, my dear uncle, and that you

have lost one of your greatest pleasures—that of doing good, and making

all happy around you.”

“Well, my dear Emma, if I have lost the pleasure of doing good, it is

the will of Heaven that it should be so, and we ought to be thankful

that, if not dispensing charity, at all events, we are not the objects

of charity to others; that we are independent, and earning an honest

livelihood. People may be very happy, and feel the most devout gratitude

on the anniversary of so great a mercy, without having a turkey for

dinner.”

“I

was not in earnest about the turkey, my dear uncle. It was the

association of ideas connected by long habit, which made me think of our

Christmas times at Wexton Hall; but, indeed, my dear uncle, if there was

regret, it was not for myself so much as for you,” replied Emma, with

tears in her eyes.

“Perhaps I spoke rather too severely, my dearest Emma,” said Mr

Campbell; “but I did not like to hear such a solemn day spoken of as if

it were commemorated merely by the eating of certain food.”

“It was foolish of me,” replied Emma, “and it was said thoughtlessly.”

Emma went up to Mr Campbell and kissed him, and Mr Campbell said, “Well,

I hope there will be a turkey, since you wish for one.”

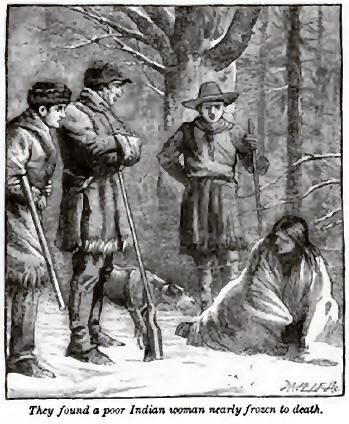

The hunters did not return till late, and when they appeared in sight,

Percival, who had descried them, came in and said that they were very

well loaded, and were bringing in their game slung upon a pole.

Mary and Emma went out of the door to meet their cousins. That there was

a heavy load carried on a pole between Martin and Alfred was certain,

but they could not distinguish what it consisted of. As the party

arrived at the palisade gates, however, they discovered that it was not

game, but a human being, who was carried on a sort of litter made of

boughs.

“What is it, Alfred!” said Mary.

“Wait till I recover my breath,” said Alfred, as he reached the door,

“or ask Henry, for I’m quite knocked up.”

Henry then went with his cousins into the house, and explained to them

that as they were in pursuit of the wild turkeys, Oscar had stopped

suddenly and commenced baying; that they went up to the dog, and, in a

bush, they found a poor Indian woman nearly frozen to death, and with a

dislocation of the ankle, so severe that her leg was terribly swelled,

and she could not move. Martin had spoken to her in the Indian tongue,

and she was so exhausted with cold and hunger, that she could just tell

him that she belonged to a small party of Indians who had been some days

out hunting, and a long way from where they had built their winter

lodges; that she had fallen with the weight which she had to carry, and

that her leg was so bad, she could not go on with them, that they had

taken her burden, and left her to follow them when she could.

“Yes,” continued Alfred; “left the poor creature without food, to perish

in the snow. One day more, and it would have been all over with her. It

is wonderful how she can have lived through the two last nights as she

was. But Martin says the Indians always do leave a woman to perish in

this way, or recover as she can, if she happens to meet with an

accident.”

“At all events, let us bring her in at once,” said Mr Campbell. “I will

first see if my surgical assistance can be of use, and after that we

will do what we can for her. How far from this did you find her?”

“About eight miles,” replied Henry; “and Alfred has carried her almost

the whole way; Martin and I have relieved each other, except once, when

I took Alfred’s place.”

“And so you perceive, Emma, instead of a wild turkey, I have brought an

Indian squaw,” said Alfred.

“I

love you better for your kindness, Alfred,” replied Emma, “than if you

had brought me a waggon-load of turkeys.”

In

the meantime, Martin and Henry brought in the poor Indian, and laid her

down on the floor at some distance from the fire, for though she was

nearly dead with the cold, too sudden an exposure to heat would have

been almost equally fatal. Mr Campbell examined her ankle, and with a

little assistance reduced the dislocation. He then bound up her leg and

bathed it with warm vinegar, as a first application. Mrs Campbell and

the two girls chafed the poor creature’s limbs till the circulation was

a little restored, and then they gave her something warm to drink. It

was proposed by Mrs Campbell that they should make up a bed for her on

the floor of the kitchen. This was done in a corner near to the

fireplace, and in about an hour their patient fell into a sound sleep.

“It is lucky for her that she did not fall into that sleep before we

found her,” said Martin; “she would never have awoke again.”

“Most certainly not,” replied Mr Campbell. “Have you any idea what tribe

she is of, Martin?”

“Yes, sir; she is one of the Chippeways; there are many divisions of

them, but I will find out when she wakes again to which she belongs; she

was too much exhausted when we found her, to say much.”

“It appears very inhuman leaving her to perish in that way,” observed

Mrs Campbell.

“Well, ma’am, so it does; but necessity has no law. The Indians could

not, if they would, have carried her, perhaps, one hundred miles. It

would have, probably, been the occasion of more deaths, for the cold is

too great now for sleeping out at nights for any time, although they do

contrive with the help of a large fire to stay out sometimes.”

“Self-preservation is the first law of nature, certainly,” observed Mr

Campbell; “but, if I recollect right, the savages do not value the life

of a woman very highly.”

“That’s a fact, sir,” replied Martin; “not much more, I reckon, than you

would a beast of burden.”

“It is always the case among savage nations,” observed Mr Campbell; “the

first mark of civilisation is the treatment of the other sex, and in

proportion as civilisation increases, so are the women protected and

well used. But your supper is ready, my children, and I think after your

fatigue and fasting you must require it.”

“I

am almost too tired to eat,” observed Alfred. “I shall infinitely more

enjoy a good sleep under my bear skins. At the same time I’ll try what I

can do,” continued he, laughing, and taking his seat at table.

Notwithstanding Alfred’s observation, he contrived to make a very hearty

supper, and Emma laughed at his appetite after his professing that he

had so little inclination to eat.

“I

said I was too tired to eat, Emma, and so I felt at the time; but as I

became more refreshed my appetite returned,” replied Alfred, laughing,

“and notwithstanding your jeering me, I mean to eat some more.”

“How long has John been away?” said Mr Campbell.

“Now nearly a fortnight,” observed Mrs Campbell; “he promised to come

here on Christmas-day. I suppose we shall see him to-morrow morning.”

“Yes, ma’am; and old Bone will come with him, I dare say. He said as

much to me when he was going away the last time. He observed that the

boy could not bring the venison, and perhaps he would

if he had any, for he knows that people like plenty of meat on

Christmas-day.”

“I

wonder whether old Malachi is any way religious,” observed Mary. “Do you

think he is, Martin?”

“Yes, ma’am; I think he feels it, but does not shew it. I know from

myself what are, probably, his feelings on the subject. When I have been

away for weeks and sometimes for months, without seeing or speaking to

anyone, all alone in the woods, I feel more religious than I do when at

Quebec on my return, although I do go to church. Now old Malachi has, I

think, a solemn reverence for the Divine Being, and strict notions of

duty, so far as he understands it—but as he never goes to any town or

mixes with any company, so the rites of religion, as I may call them,

and the observances of the holy feasts, are lost to him, except as a

sort of dream of former days, before he took to his hunter’s life.

Indeed, he seldom knows what day or even what month it is. He knows the

seasons as they come and go, and that’s all. One day is the same as

another, and he cannot tell which is Sunday, for he is not able to keep

a reckoning. Now, ma’am, when you desired Master John to be at home on

the Friday fortnight because it was Christmas-day, I perceived old

Malachi in deep thought: he was recalling to mind what Christmas-day

was; if you had not mentioned it, the day would have passed away like

any other; but you reminded him, and then it was that he said he would

come if he could. I’m sure that now he knows it is Christmas-day, he

intends to keep it as such.”

“There is much truth in what Martin says,” observed Mr Campbell; “we

require the seventh day in the week and other stated seasons of devotion

to be regularly set apart, in order to keep us in mind of our duties and

preserve the life of religion. In the woods, remote from communion with

other Christians, these things are easily forgotten, and when once we

have lost our calculation, it is not to be recovered. But come, Alfred,

and Henry, and Martin must be very tired, and we had better all go to

bed. I will sit up a little while to give some drink to my patient, if

she wishes it. Good night, my children.”