The next morning, a little after daybreak, Martin and

John made their appearance, leading the magnificent dog which Captain

Sinclair had given to John. Like most large dogs, Oscar appeared to be

very good-tempered, and treated the snarling and angry looks of the

other dogs with perfect contempt.

“It is, indeed, a noble animal,” said Mr Campbell, patting its head.

“It’s a fine creature,” observed Malachi, “a wolf would stand no chance

against him, and even a bear would have more on its hands than it could

well manage, I expect; but, come here, boy,” said the old hunter to

John, leading the way outside of the door.

“You’d better leave the dog, John,” said Malachi, “the crittur will be

of use here, but no good to us.”

John made no reply, and the hunter continued, “I say it will be of use

here, for the girls might meet with another wolf, or the house might be

attacked; but good hunters don’t want dogs. Is it to watch for us, and

give us notice of danger? Why that’s our duty, and we must trust to

ourselves, and not to an animal. Is it to hunt for us? Why no dog can

take a deer so well as we can with our rifles; a dog may discover us

when we wish to be hidden; a dog’s track will mark us out when we would

wish our track to be doubted. The animal will be of no utility ever to

us, John, and may do us harm, ’specially now the snow’s on the ground.

In the summer-time, you can take him and teach him how to behave as a

hunter’s dog should behave; but we had better leave him now, start at

once.”

John nodded his head in assent, and then went indoors.

“Good-bye,” said John, going up to his mother and cousins; “I shall not

take the dog.”

“Won’t take the dog! well, that’s very kind of you, John,” said Mary,

“for we were longing to have him to protect us.”

John shouldered his rifle, made a sign to Strawberry-Plant, who rose,

and looking kindly at Mrs Campbell and the girls, without speaking,

followed John out of the hut. Malachi certainly was not very polite, for

he walked off, in company with John and the squaw, without taking the

trouble to say “Good-bye.” It must, however, be observed that he was in

conversation with Martin, who accompanied them on the way.

The winter had now become very severe. The thermometer was twenty

degrees below freezing point, and the cold was so intense, that every

precaution was taken against it. More than once Percival, whose business

it was to bring in the firewood, was frost-bitten, but as Mrs Campbell

was very watchful, the remedy of cold snow was always successfully

applied. The howling of the wolves continued every night, but they were

now used to it, and the only effect was, when one came more than usually

close to the house, to make Oscar raise his head, growl, listen awhile,

and then lie down to sleep again. Oscar became very fond of the girls,

and was their invariable companion whenever they left the house.

Alfred, Martin, and Henry went out almost daily on hunting excursions;

indeed, as there were no crops in the barn, they had little else to do.

Mr Campbell remained at home with his wife and nieces; occasionally, but

not very often, Percival accompanied the hunters; of Malachi and John

they saw but little; John returned about every ten days, but although he

adhered to his promise, his anxiety to go back to Malachi was so very

apparent, and he was so restless, that Mrs Campbell rather wished him to

be away, than remain at home so much against his will.

Thus passed away the time till the year closed in; confined as they were

by the severity of the weather, and having little or nothing to do, the

winter appeared longer and more tedious than it would have done if they

had been settled longer, and had the crops to occupy their attention;

for it is in the winter that the Canadian farmer gets through all his

thrashing and other work connected with his farm, preparatory for the

coming spring. This being their first winter, they had, of course, no

crops gathered in, and were, therefore, in want of employment. Mrs

Campbell and her nieces worked and read, and employed themselves in

every way that they could, but constantly shut up within doors, they

could not help feeling the monotony and ennui of

their situation. The young men found occupation and amusement in the

chase; they brought in a variety of animals and skins, and the evenings

were generally devoted to a narration of what occurred in the day during

their hunting excursions, but even these histories of the chase were at

last heard with indifference. It was the same theme, only with

variations, over and over again, and there was no longer much excitement

in listening.

“I

wonder when John will come back again,” observed Emma to her sister, as

they were sitting at work.

“Why he only left two days ago, so we must not expect him for some

time.”

“I

know that. I wonder if Oscar would kill a wolf, I should like to take

him out and try.”

“I

thought you had had enough of wolves already, Emma,” replied Mary.

“Yes, well, that old Malachi will never bring us any more news about the

Indians,” continued Emma, yawning.

“Why I do not think that any news about them is likely to be pleasant

news, Emma, and therefore why should you wish it.”

“Why, my dear Mary, because I want some news; I want something to excite

me, I feel so dull. It’s nothing but stitch, stitch, all day, and I am

tired of always doing the same thing. What a horrid thing a Canadian

winter is, and not one-half over yet.”

“It is very dull and monotonous, my dear Emma, I admit, and if we had

more variety of employment, we should find it more agreeable, but we

ought to feel grateful that we have a good house over our heads, and

more security than we anticipated.”

“Almost too much security, Mary; I begin to feel that I could welcome an

Indian even in his war-paint, just by way of a little change.”

“I

think you would soon repent of your wish, if it were gratified.”

“Very likely, but I can’t help wishing it now. When will they come home?

What o’clock is it? I wonder what they’ll bring, the old story I

suppose, a buck; I’m sick of venison.”

“Indeed, Emma, you are wrong to feel such discontent and weariness.”

“Perhaps I am, but I have not walked a hundred yards for nearly one

hundred days, and that will give one the blues, as they call them, and I

do nothing but yawn, yawn, yawn, for want of air and exercise. Uncle

won’t let us move on account of that horrid wolf. I wonder how Captain

Sinclair is getting on at the fort, and whether he is as dull as we

are.”

To

do Emma justice, it was seldom that she indulged herself in such

lamentings, but the tedium was more than her high flow of spirits could

well bear. Mrs Campbell made a point of arranging the household, which

gave her occupation, and Mary from natural disposition did not feel the

confinement as much as Emma did; whenever, therefore, she did shew

symptoms of restlessness or was tempted to utter a complaint, they

reasoned with and soothed, but never reproached her.

The day after this conversation, Emma, to amuse herself, took a rifle

and vent out with Percival. She fired several shots at a mark, and by

degrees acquired some dexterity; gradually she became fond of the

exercise, and not a day passed that she and Percival did not practise

for an hour or two, until at last Emma could fire with great precision.

Practice and a knowledge of the perfect use of your weapon gives

confidence, and this Emma did at last acquire. She challenged Alfred and

Henry to fire at the bull’s-eye with her, and whether by their gallantry

or her superior dexterity, she was declared victor. Mr and Mrs Campbell

smiled when Emma came in and narrated her success, and felt glad that

she had found something which afforded her amusement.

It

happened that one evening the hunters were very late; it was a clear

moonlight night, but at eight o’clock they had not made their

appearance; Percival had opened the door to go out for some firewood

which had been piled within the palisades, and as it was later than the

usual hour for locking the palisade gates, Mr Campbell had directed him

so to do. Emma, attracted by the beauty of the night, was at the door of

the house, when the howl of a wolf was heard close to them; the dogs,

accustomed to it, merely sprang on their feet, but did not leave the

kitchen fire; Emma went out, and looked through the palisades to see if

she could perceive the animal, and little Trim, the terrier, followed

her. Now Trim was so small, that he could creep between the palisades,

and as soon as he was close to them, perceiving the wolf, the courageous

little animal squeezed through them and flew towards it, barking as loud

as he could. Emma immediately ran in, took down her rifle and went out

again, as she knew that poor Trim would soon be devoured. The

supposition was correct, the wolf instead of retreating closed with the

little dog and seized it. Emma, who could now plainly perceive the

animal, which was about forty yards from her, took aim and fired, just

as poor Trim gave a loud yelp. Her aim was good, and the wolf and dog

lay side by side. Mr and Mrs Campbell, and Mary, hearing the report of

the rifle, ran out, and found Percival and Emma at the palisades behind

the house.

“I

have killed him, aunt,” said Emma, “but I fear he has killed poor little

Trim; do let us go out and see.”

“No, no, my dear Emma, that must not be; your cousins will be home soon,

and then we shall know how the case stands; but the risk is too great.”

“Here they come,” said Percival, “as fast as they can run.”

The hunters were soon at the palisade door and admitted; they had no

game with them. Emma jeered them for coming back empty-handed.

“No, no, my little cousin,” replied Alfred, “we heard the report of a

rifle, and we threw down our game, that we might sooner come to your

assistance if you required it. What was the matter?”

“Only that I have killed a wolf, and am not allowed to bring in my

trophy,” replied Emma. “Come, Alfred, I may go with you and Martin.”

They went to the spot, and found the wolf was dead, and poor Trim dead

also by his side. They took in the body of the little dog, and left the

wolf till the morning, when Martin said he would skin it for Miss Emma.

“And I’ll make a footstool of it,” said Emma; “that shall be my revenge

for the fright I had from the other wolf. Come, Oscar, good dog; you and

I will go wolf-hunting. Dear me, who would have thought that I should

have ever killed a wolf—poor little Trim!”

Martin said it would be useless to return for the venison, as the wolves

had no doubt eaten it already; so they locked the palisade gate, and

went into the house.

Emma’s adventure was the topic of the evening, and Emma herself was much

pleased at having accomplished such a feat.

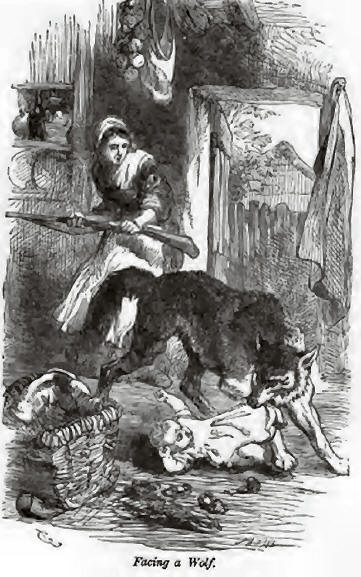

“Well,” said Martin, “I never knew but one woman who faced a wolf except

Miss Emma.”

“And who was that, Martin?” said Mrs Campbell.

“It was a wife of one of our farmers, ma’am; she was at the outhouse

doing something, when she perceived a wolf enter the cottage-door, where

there was nobody except the baby in the cradle. She ran back and found

the wolf just lifting the infant out of the cradle by its clothes. The

animal looked at her with his eyes flashing; but having its mouth full,

it did not choose to drop the baby, and spring at her; all it wanted was

to get clear off with its prey. The woman had presence of mind enough to

take down her husband’s rifle and point it to the wolf, but she was so

fearful of hurting the child, that she did not put the muzzle to its

head, but to its shoulder. She fired just as the wolf was making off,

and the animal fell, and could not get on its feet again, and it then

dropped the child out of its mouth to attack the mother. The woman

caught the child up, but the wolf gave her a severe bite on the arm, and

broke the bone near the wrist. A wolf has a wonderful strong jaw, ma’am.

However, the baby was saved, and neighbours came and despatched the

animal.”

“What a fearful position for a mother to be in!” exclaimed Mrs Campbell.

“Where did that happen?”

“On the White Mountains, ma’am,” replied Martin. “Malachi Bone told me

the story; he was born there.”

“Then he is an American.”

“Well, ma’am, he is an American because he was born in this country, but

it was English when he was born, so he calls himself an Englishman.”

“I

understand,” replied Mrs Campbell, “he was born before the colonies

obtained their independence.”

“Yes, ma’am, long before; there’s no saying how old he is. When I was

quite a child, I recollect he was then reckoned an old man; indeed, the

name the Indians gave to

him proves it. He then was called the ‘Grey Badger.’”

“But is he so very old, do you really think, Martin?”

“I

think he has seen more than sixty snows, ma’am; but not many more; the

fact is, his hair was grey before he was twenty years old; he told me so

himself, and that’s one reason why the Indians are so fearful of him.

They have it from their fathers that the Grey Badger was a great hunter,

as Malachi was more than forty years ago; so they imagine as his hair

was grey then, he must have been a very old man at that time back, and

so to them he appears to live for ever, and they consider him as

charmed, and to use their phrase ‘great medicine.’

I’ve heard some Indians declare that Malachi has seen one hundred and

fifty winters, and they really believe it. I never contradicted them, as

you may imagine.”

“Does he live comfortably?”

“Yes, ma’am, he does; his squaw knows what he wants, and does what she

is bid. She is very fond of the old man, and looks upon him, as he

really is to her, as a father. His lodge is always full of meat, and he

has plenty of skins. He don’t drink spirits, and if he has tobacco for

smoking, and powder and ball, what else can he want?”

“Happy are they whose wants are so few,” observed Mr Campbell. “A man in

whatever position in life, if he is content, is certain to be happy. How

true are the words of the poet:—

“Man wants but little here below,

Nor wants that little long!”

“Malachi Bone, is a happier man than hundreds in England who live in

luxury. Let us profit, my dear children, by his example, and learn to be

content with what Heaven has bestowed upon us. But it is time to retire.

The wind has risen, and we shall have a blustering night. Henry, fetch

me the book.”