On the Monday morning, Alfred and Martin went to the

cow-house, and slaughtered the bullock which they had obtained from the

commandant of the fort. When it was skinned it was cut up, and carried

to the store-house, where it was hung up for their winter consumption.

As

the party were sitting down to dinner, they were greeted by Captain

Sinclair and a young lieutenant of the garrison. It hardly need be said

that the whole family were delighted to see them. They had come overland

in their snow-shoes, and brought some partridges, or grouse, as they are

some times called, which they had shot on their way. Captain Sinclair

had obtained leave from the commandant to come over and see how the

Campbells were getting on. He had no news of any importance, as they had

had no recent communication with Quebec or Montreal; all was well at the

fort, and Colonel Forster had sent his compliments, and begged, if he

could be useful, that they would let him know. Captain Sinclair and his

friend sat down to dinner, and talked more than they ate, asking

questions about everything.

“By-the-bye, Mr Campbell, where have you built your pigsties?”

“Inside the palisade, next to the fowl-house.”

“That is well,” replied Captain Sinclair, “for otherwise you may be

troubled by the wolves, who are very partial to pork or mutton.”

“We have been

troubled with them,” replied Emma; “at least with their howlings at

night, which make me tremble as I lie awake in bed.”

“Never mind their howling, Miss Emma; we have plenty of them round the

fort, I can assure you; unless attacked, they will not attack you, at

least I never knew an instance, although I must confess that I have

heard of them.”

“You will, of course, sleep here to-night?”

“Yes, we will, if you have a bear or buffalo skin to spare,” replied

Captain Sinclair.

“We will manage it, I have no doubt,” said Mr Campbell.

“And if you could manage, Captain Sinclair,” said Emma, somewhat archly,

“as you say that they are not dangerous animals, to bring us in a few

skins to-night, it would make the matter easy.”

“Emma, how can you talk such nonsense?” cried Mary Percival. “Why should

you ask a guest to undertake such a service? Why have you not proposed

it to Alfred or Henry, or even Martin?”

“We will both try, if you please,” replied Alfred.

“I

must put my veto on any such attempts, Alfred,” said Mr Campbell. “We

have sufficient danger to meet, without running into it voluntarily, and

we have no occasion for wolves’ skins just now. I shall, however,

venture to ask your assistance to-morrow morning. We wish to haul up the

fishing-punt before the ice sets in on the lake, and we are not

sufficiently strong-handed.”

During the day, Captain Sinclair took Alfred aside to know if the old

hunter had obtained any information relative to the Indians. Alfred

replied, that they expected him every day, but as yet had not received

any communication from him. Captain Sinclair stated that they were

equally ignorant at the fort as to what had been finally arranged, and

that Colonel Forster was in hopes that the hunter would by this time

have obtained some intelligence.

“I

should not be surprised if Malachi Bone were to come here

to-morrow morning,” replied Alfred. “He has been away a long while, and,

I am sure, is as anxious to have John with him as John is impatient to

go.”

“Well, I hope he will; I shall be glad to have something to tell the

Colonel, as I made the request upon that ground. I believe, however, he

was very willing that I should find an excuse for coming here, as he is

more anxious about your family than I could have supposed. How well your

cousin Mary is looking.”

“Yes; and so is Emma, I think. She has grown half a head since she left

England. By-the-bye, you have to congratulate me on my obtaining my rank

as Lieutenant.”

“I

do indeed, my dear fellow,” replied Captain Sinclair. “They will be

pleased to hear it at the fort. When will you come over?”

“As soon as I can manage to trot a little faster upon these snow-shoes.

If, however, the old hunter does not come to-morrow, I will go to the

fort as soon as he brings us any news.”

The accession to their party made them all very lively, and the evening

passed away very agreeably. At night, Captain Sinclair and Mr Gwynne

were ushered into the large bedroom where all the younger male portion

of the family slept, and which, as we before stated, had two spare

bed-places.

The next morning, Captain Sinclair would have accompanied the Misses

Percival on their milking expedition, but as his services were required

to haul up the fishing-punt, he was obliged to go down, with all the

rest of the men, to assist; Percival and John were the only ones left at

home with Mrs Campbell. John, after a time, having, as usual, rubbed

down his rifle, threw it on his shoulder, and, calling the dogs which

lay about, sallied forth for a walk, followed by the whole pack except

old Sancho, who invariably accompanied the girls to the cow-house.

Mary and Emma tripped over the new-beaten snow-path to the cow-house,

merry and cheerful, with their pails in their hands, Emma laughing at

Captain Sinclair’s disappointment at not being permitted to accompany

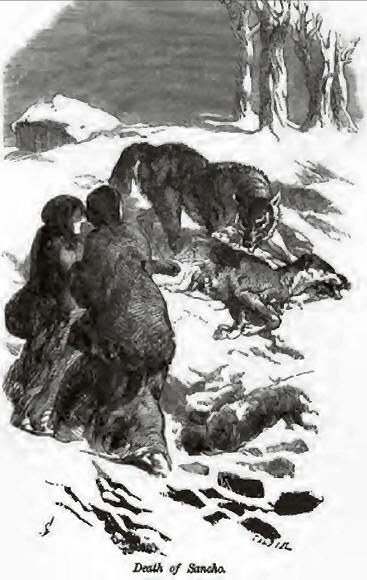

them. They had just arrived at the cow-house, when old Sancho barked

furiously, and sprang to the side of the building behind them, and in a

moment afterwards rolled down the snow heap which he had sprung over,

holding on and held fast by a large black wolf. The struggle was not

very long, and during the time that it lasted the girls were so

panic-struck, that they remained like statues within two yards of the

animals. Gradually the old dog was overpowered by the repeated snapping

bites of the wolf, yet he fought nobly to the last, when he dropped

under the feet of the wolf, his tongue hanging out, bleeding profusely

and lifeless. As soon as his adversary was overpowered, the enraged

animal, with his feet upon the body of the dog, bristling his hair and

showing his powerful teeth, was evidently about to attack the young

women. Emma threw her arm round Mary’s waist, advancing her body so as

to save her sister. Mary attempted the same, and then they remained

waiting in horror for the expected spring of the animal, when of a

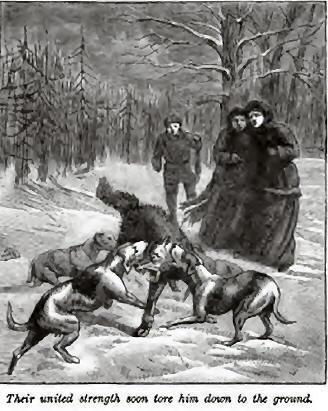

sudden the other dogs came rushing forward, cheered on by John, and flew

upon the animal.

Their united strength soon tore him down to the ground, and John coming

up, as the wolf defended himself against his new assailants, put the

muzzle of his rifle to the animal’s head, and shot it dead.

The two sisters had held up during the whole of this alarming struggle;

but as soon as they perceived the wolf was dead and that they were safe,

Mary could stand no longer, and sank down on her knees, supporting her

sister, who had become insensible.

If

John showed gallantry in shooting the wolf, he certainly showed very

little towards his cousins. He looked at Mary, nodded his head towards

the wolfs body, and saying “He’s dead,” shouldered his rifle, turned

round and walked back to the house.

On

his return, he found that the party had just come back from hauling up

the punt, and were waiting the return of the Misses Percival to go to

breakfast.

“Was that you who fired just now, John?” said Martin.

“Yes,” replied John.

“What did you fire at?” said Alfred.

“A

wolf,” replied John.

“A

wolf! where?” said Mr Campbell.

“At the cow-lodge,” replied John.

“The cow-lodge!” said his father.

“Yes; killed Sancho!”

“Killed Sancho! why, Sancho was with your cousins!”

“Yes,” replied John.

“Then, where did you leave them?”

“With the wolf,” replied John, wiping his rifle very coolly.

“Merciful Heaven!” cried Mr Campbell, as Mrs Campbell turned pale; and

Alfred, Captain Sinclair, Martin, and Henry, seizing their rifles,

darted out from the house, and ran with all speed in the direction of

the cow-house.

“My poor girls!” exclaimed Mr Campbell.

“Wolfs dead, father,” said John.

“Dead! Why didn’t you say so, you naughty boy?” cried Mrs Campbell.

“I

wasn’t asked,” replied John.

In

the meantime the other party had gained the cow-house; and, to their

horror, beheld the wolf and dog dead, and the two young women lying on

the snow, close to the two animals; for Mary had fainted away shortly

after John had walked off. They rushed towards the bodies of the two

girls, and soon discovered that they were not hurt. In a short time they

were recovered, and were supported by the young men to the house.

As

soon as they arrived, Mrs Campbell took them into their room, that they

might rally their spirits, and in a quarter of an hour returned to the

party outside, who eagerly inquired how they were.

“They are much more composed,” replied Mrs Campbell; “and Emma has begun

to laugh again; but her laugh is rather hysterical and forced; they will

come out at dinnertime. It appears that they are indebted to John for

their preservation, for they say the wolf was about to spring upon them

when he came to their assistance. We ought to be very grateful to Heaven

for their preservation. I had no idea, after what Martin said about the

wolves, that they were so dangerous.”

“Why, ma’am, it is I that am most to blame, and that’s the fact,”

replied Martin. “When we killed the bullock I threw the offal on the

heap of snow close to the cow-lodge, meaning that the wolves and other

animals might eat it at night, but it seems that this animal was hungry,

and had not left his meal when the dog attacked him, and that made the

beast so rily and savage.”

“Yes; it was the fault of Martin and me,” replied Alfred. “Thank Heaven

it’s no worse!”

“So far from its being a subject of regret, I consider it one of

thankfulness,” replied Mr Campbell. “This might have happened when there

was no one to assist, and our dear girls might have been torn to pieces.

Now that we know the danger, we may guard against it for the future.”

“Yes, sir,” replied Martin; “in future some of us will drive the cows

home, to be milked every morning and evening; inside the palisade there

will be no danger. Master John, you have done well. You see, ma’am,”

continued Martin, “what I said has come true. A rifle in the hands of a

child is as deadly a weapon as in the hands of a strong man.”

“Yes, if courage and presence of mind attend its uses,” replied Mr

Campbell. “John, I am very much pleased with your conduct.”

“Mother called me naughty,” replied John rather sulkily.

“Yes, John, I called you naughty, for not telling us the wolf was dead,

and leaving us to suppose that your cousins were in danger; not for

killing the wolf. Now I kiss you, and thank you for your bravery and

good conduct.”

“I

shall tell all the officers at the fort, what a gallant little fellow

you are, John,” said Captain Sinclair; “there are very few of them who

have shot a wolf, and what is more, John, I have a beautiful dog, which

one of the officers gave me the other day in exchange for a pony, and I

will bring it over, and make it a present to you for your own dog. He

will hunt anything, and he is very powerful—quite able to master a wolf,

if you meet with one. He is half mastiff and half Scotch deerhound, and

he stands as high as this,” continued Captain Sinclair, holding his hand

about as high as John’s shoulder.

“I’ll go to the fort with you,” said John, “and bring him back.”

“So you shall, John, and I’ll go with you,” said Martin, “if master

pleases.”

“Well,” replied Mr Campbell, “I think he may; what with Martin, his own

rifle, and the dog, John will, I trust, be safe enough.”

“Certainly, I have no objection,” said Mrs Campbell, “and many thanks to

you, Captain Sinclair.”

“What’s the dog’s name?” said John.

“Oscar,” replied Captain Sinclair. “If you let him walk out with your

cousins, they need not fear a wolf. He will never be mastered by one, as

poor Sancho was.”

“I’ll lend him sometimes,” replied John.

“Always; when you don’t want him yourself, John.”

“Yes, always,” replied John, who was going out of the door.

“Where are you going, dear,” said Mrs Campbell.

“Going to skin the wolf,” replied John, walking away.

“Well, he’ll be a regular keen hunter,” observed Martin. “I dare say old

Bone has taught him to flay an animal. However I’ll go and help him, for

it’s a real good skin.” So saying, Martin followed John.

“Martin ought to have known better than to leave the offal where he

did,” observed Captain Sinclair.

“We must not be too hard, Captain Sinclair,” said Alfred. “Martin has a

contempt for wolves, and that wolf would not have stood his ground had

it been a man instead of two young women who were in face of him. Wolves

are very cunning, and I know will attack a woman or child when they will

fly from a man. Besides, it is very unusual for a wolf to remain till

daylight, even when there is offal to tempt him. It was the offal, the

animal’s extreme hunger, and the attack of the dog—a combination of

circumstances—which produced the event. I do not see that Martin can be

blamed, as one cannot foresee everything.”

“Perhaps not,” replied Captain Sinclair, “and ‘all’s well that ends

well.’”

“Are there any other animals to fear?” inquired Mrs Campbell.

“The bear is now safe for the winter in the hollow of some tree or under

some root, where he has made a den. It will not come out till the

spring. The catamount or panther is a much more dangerous animal than

the wolf; but it is scarce. I do think, however, that the young ladies

should not venture out, unless with some rifles in company, for fear of

another mischance. We have plenty of lynxes here; but I doubt if they

would attack even a child, although they fight when assailed, and bite

and claw severely.”

The Misses Percival now made their appearance. Emma was very merry, but

Mary rather grave. Captain Sinclair, having shaken hands with them both,

said—

“Why, Emma, you appear to have recovered sooner than your sister!”

“Yes,” replied Emma; “but I was much more frightened than she was, and

she supported me, or I should have fallen at the wolf’s feet. I yielded

to my fears; Mary held up against hers; so, as her exertions were much

greater than mine, she has not recovered from them so soon. The fact is,

Mary is brave when there is danger, and I am only brave when there is

none.”

“I

was quite as much frightened as you, my dear Emma,” said Mary Percival;

“but we must now help our aunt, and get dinner ready on the table.”

“I

cannot say that I have a wolfish appetite this morning,” replied Emma,

laughing; “but Alfred will eat for me and himself too.” In a few minutes

dinner was on the table, and they all sat down without waiting for

Martin and John, who were still busy skinning the wolf.