The next morning, when they assembled at breakfast, after

Mr Campbell had read the prayers, Mary Percival said, “Did you hear that

strange and loud noise last night? I was very much startled with it;

but, as nobody said a word, I held my tongue.”

“Nobody said a word, because everybody was fast asleep, I presume,” said

Alfred; “I heard nothing.”

“It was like the sound of cart-wheels at a distance, with whistling and

hissing,” said Mary.

“I

think I can explain it to you, as I was up during the night, Miss

Percival,” said Captain Sinclair. “It is a noise you must expect every

night during the summer season; but one to which you will soon be

accustomed.”

“Why, what was it?”

“Frogs,—nothing more; except, indeed, the hissing, which, I believe, is

made by the lizards. They will serenade you every night. I only hope you

will not be disturbed by anything more dangerous.”

“Is it possible that such small creatures can make such a din?”

“Yes, when thousands join in the concert; I may say millions.”

“Well, I thank you for the explanation, Captain Sinclair, as it has been

some relief to my mind.”

After breakfast, Martin (we shall for the future leave out his surname)

informed Mr Campbell that he had seen Malachi Bone, the hunter, who had

expressed great dissatisfaction at their arrival, and his determination

to quit the place if they remained.

“Surely, he hardly expects us to quit the place to please him?”

“No,” replied Martin; “but if he were cankered in disposition, which I

will say Malachi is not, he might make it very unpleasant for you to

remain, by bringing the Indians about you.”

“Surely, he would not do that?” said Mrs Campbell.

“No, I don’t think he would,” replied Martin; “because, you see, it’s

just as easy for him to go further off.”

“But why should we drive him away from his property any more than we

leave our own?” observed Mrs Campbell.

“He says he won’t be crowded, ma’am; he can’t bear to be crowded.”

“Why, there’s a river between us.”

“So there is, ma’am, but still that’s his feeling. I said to him that if

he would go, I daresay Mr Campbell would buy his allotment of him, and

he seems quite willing to part with it.”

“It would be a great addition to your property, Mr Campbell,” observed

Captain Sinclair. “In the first place, you would have the whole of the

prairie and the right of the river on both sides, apparently of no

consequence now, but as the country fills up, most valuable.”

“Well,” replied Mr Campbell, “as I presume we shall remain here, or, at

all events, those who survive me will, till the country fills up, I

shall be most happy to make any arrangement with Bone for the purchase

of his property.”

“I’ll have some more talk with him, sir,” replied Martin.

The second day was passed as was the first, in making preparations for

erecting the house, which, now that they had obtained such unexpected

help, was, by the advice of Captain Sinclair, considerably enlarged

beyond the size originally intended. As Mr Campbell paid the soldiers

employed a certain sum per day for their labour, he had less scruple in

employing them longer. Two of them were good carpenters, and a sawpit

had been dug, that they might prepare the doors and the frames for the

window-sashes which Mr Campbell had taken the precaution to bring with

him. On the third day a boat arrived from the fort bringing the men’s

rations and a present of two fine bucks from the commandant. Captain

Sinclair went in the boat to procure some articles which he required,

and returned in the evening. The weather continued fine, and in the

course of a week a great deal of timber was cut and squared. During this

time Martin had several meetings with the old hunter, and it was agreed

that he should sell his property to Mr Campbell. Money he appeared to

care little about—indeed it was useless to him; gunpowder, lead, flints,

blankets, and tobacco, were the principal articles requested in the

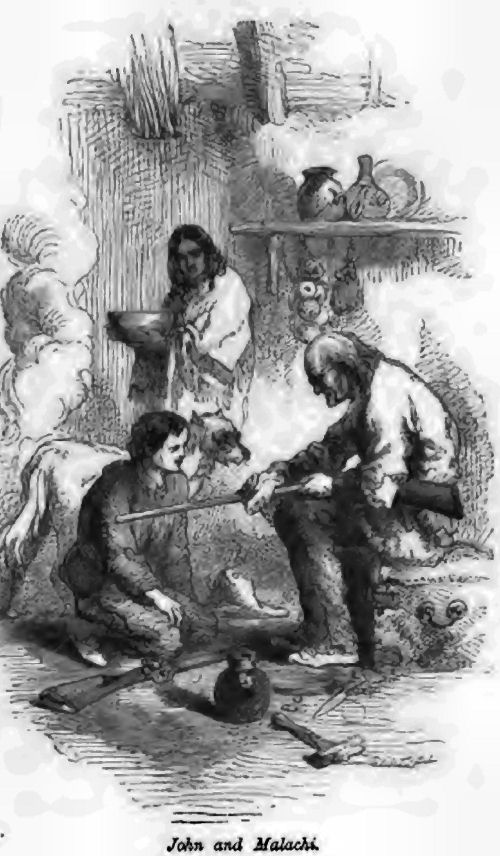

barter; the amount, however, was not precisely settled. An intimacy had

been struck up between the old hunter and John; in what manner it was

difficult to imagine, as they both were very sparing of their words; but

this was certain, that John had contrived to get across the stream

somehow or another, and was now seldom at home to his meals. Martin

reported that he was in the lodge of the old hunter, and that he could

come to no harm; so Mrs Campbell was satisfied.

“But what does he do there, Martin?” said Mrs Campbell, as they were

clearing the table after supper.

“Just nothing but look at the squaw, or at Malachi cleaning his gun, or

anything else he may see. He never speaks, that I know of, and that’s

why he suits old Malachi.”

“He brought home a whole basket of trout this afternoon,” observed Mary;

“so he is not quite idle.”

“No, miss, he’s fishing at daylight, and gives one-half to you and the

other to old Bone. He’ll make a crack hunter one of these days, as old

Malachi says. He can draw the bead on the old man’s rifle in good style

already, I can tell you.”

“How do you mean, Martin,” said Mrs Campbell.

“I

mean that he can fire pretty true, ma’am, although it’s a heavy gun for

him to lift; a smaller one would be better for him.”

“But is he not too young to be trusted with a gun, uncle?” said Mary.

“No, miss,” interrupted Martin, “you can’t be too young here; the sooner

a boy is useful the better; and the boy with a gun is almost as good as

a man; for the gun kills equally well if pointed true. Master Percival

must have his gun as soon as I am at leisure to teach him.”

“I

wish you were at leisure now, Martin,” cried Percival.

“You forget, aunt, that you promised to learn to load and fire a rifle

yourself,” said Mary.

“No, I do not; and I intend to keep my word, as soon as there is time;

but John is so very young.”

“Well, Mary, I suppose we must enlist too?” said Emma.

“Yes; we’ll be the female rifle brigade,” replied Mary, laughing.

“I

really quite like the idea,” continued Emma; “I will put up with no

impertinence, recollect, Alfred; excite my displeasure, and I shall take

down my rifle.”

“I

suspect you will do more execution with your eyes, Emma,” replied

Alfred, laughing.

“Not upon a catamount, as Martin calls it. Pray, what is a catamount?”

“A

painter, miss.”

“Oh! now I know; a catamount is a painter, a painter is a leopard or a

panther.—As I live, uncle, here comes the old hunter, with John trotting

at his heels. I thought he would come at last. The visit is to me, I’m

sure, for when we first met he was dumb with astonishment.”

“He well might be,” observed Captain Sinclair; “he has not often met

with such objects as you and your sister in the woods.”

“No,” replied Emma; “an English squaw must be rather a rarity.”

As

she said this, old Malachi Bone came up, and seated himself, without

speaking, placing his rifle between his knees.

“Your servant, sir,” said Mr Campbell; “I hope you are well.”

“What on earth makes you come here?” said Bone, looking round him. “You

are not fit for the wilderness! Winter will arrive soon; and then you go

back, I reckon.”

“No, we shall not,” replied Alfred, “for we have nowhere to go back to;

besides, the people are too crowded where we came from, so we came here

for more room.”

“I

reckon you’ll crowd me,” replied the hunter, “so I’ll go farther.”

“Well, Malachi, the gentleman will pay you for your clearing.”

“I

told you so,” said Martin.

“Yes, you did; but I’d rather not have seen him or his goods.”

“By goods, I suppose you mean us about you?” said Emma.

“No, girl, I didn’t mean you. I meant gunpowder and the like.”

“I

think, Emma, you are comprehended in the last word,” said Alfred.

“That is more than you are, then, for he did not mention lead,” retorted

Emma.

“Martin Super, you know I did specify lead on the paper,” said Malachi

Bone.

“You did, and you shall have it,” said Mr Campbell. “Say what your terms

are now, and I will close with you.”

“Well, I’ll leave that to Martin and you, stranger. I clear out

to-morrow.”

“To-morrow; and where do you go to?”

Malachi Bone pointed to the westward.

“You’ll not hear my rifle,” said the old hunter, after a pause; “but I’m

thinking you’ll never stay here. You don’t know what an Ingen’s life is;

it an’t fit for the like of you. No, there’s not one of you, ’cept this

boy,” continued Malachi, putting his hand to John’s head, “that’s fit

for the woods. Let him come to me. I’ll make a hunter of him; won’t I,

Martin?”

“That you will, if they’ll spare him to you.”

“We cannot spare him altogether,” replied Mr Campbell, “but he shall

visit you, if you wish it.”

“Well, that’s a promise; and I won’t go so far as I thought I would. He

has a good eye; I’ll come for him.”

The old man then rose up and walked away, John following him, without

exchanging a word with any of the party.

“My dear Campbell,” said his wife, “what do you intend to do about John?

You do not intend that the hunter should take him with him?”

“No, certainly not,” replied Mr Campbell; “but I see no reason why he

should not be with him occasionally.”

“It will be a very good thing for him to be so,” said Martin. “If I may

advise, let the boy come and go. The old man has taken a fancy to him,

and will teach him his wood craft. It’s as well to make a friend of

Malachi Bone.”

“Why, what good can he do us,” enquired Henry.

“A

friend in need is a friend indeed, sir; and a friend in the wilderness

is not to be thrown away. Old Malachi is going further out, and if

danger occurs, we shall know it from him, for the sake of the boy, and

have his help too, if we need it.”

“There is much good sense in Martin Super’s remarks, Mr Campbell,”

observed Captain Sinclair. “You will then have Malachi Bone as an

advanced guard, and the fort to fall back upon, if necessary to

retreat.”

“And, perhaps, the most useful education which he can receive to prepare

him for his future life will be from the old hunter.”

“The only one which he will take to kindly, at all events,” observed

Henry.

“Let him go, sir; let him go,” said Martin.

“I

will give no positive answer, Martin,” replied Mr Campbell. “At all

events, I will permit him to visit the old man; there can be no

objection to that:—but it is bedtime.”