Although it was now the middle of May, it was but a few

days before their departure that there was the least sign of verdure, or

the trees had burst into leaf; but in the course of the three days

before they quitted Quebec, so rapid was the vegetation, that it

appeared as if summer had come upon them all at once. The heat was also

very great, although, when they had landed, the weather was piercing

cold; but in Canada, as well as in all Northern America, the transitions

from heat to cold, and from cold to heat, are very rapid.

My

young readers will be surprised to hear that, when the winter sets in at

Quebec, all the animals required for the winter’s consumption are at

once killed. If the troops are numerous, perhaps three or four hundred

bullocks are slaughtered and hung up. Every family kill their cattle,

their sheep, pigs, turkeys, fowls, etcetera, and all are put up in the

garrets, where the carcases immediately freeze hard, and remain quite

good and sweet during the six or seven months of severe winter which

occur in that climate. When any portion of meat is to be cooked, it is

gradually thawed in lukewarm water, and after that is put to the fire.

If put at once to the fire in its frozen state, it spoils. There is

another strange circumstance which occurs in these cold latitudes; a

small fish, called the snow-fish, is caught during the winter by making

holes in the thick ice; and these fish, coming to the holes in thousands

to breathe, are thrown out with hand-nets upon the ice, where they

become in a few minutes frozen quite hard, so that, if you wish it, you

may break them in half like a rotten stick. The cattle are fed upon

these fish during the winter months. But it has been proved—which is

very strange—that if, after they have been frozen for twenty-four hours

or more, you put these fish into water and gradually thaw them as you do

the meat, they will recover and swim about again as well as ever. To

proceed, however, with our history.

Mr

Campbell found that, after all his expenses, he had still three hundred

pounds left, and this money he left in the Quebec Bank, to use as he

might find necessary. His expenditure had been very great. First, there

was the removal of so large a family, and the passage out; then he had

procured at Liverpool a large quantity of cutlery and tools, furniture,

etcetera, all of which articles were cheaper there than at Quebec. At

Quebec he had also much to purchase: all the most expensive portion of

his house; such as windows ready glazed, stoves, boarding for floors,

cupboards, and partitions; salt provisions, crockery of every

description, two small waggons ready to be put together, several casks

of nails, and a variety of things which it would be too tedious to

mention. Procuring these, with the expenses of living, had taken away

all his money, except the three hundred pounds I have mentioned.

It

was on the 13th of May that the embarkation took place, and it was not

until the afternoon that all was prepared, and Mrs Campbell and her

nieces were conducted down to the bateaux,

which lay at the wharf, with the troops already on board of them. The

Governor and his aides-de-camp, besides many other influential people of

Quebec, escorted them down, and as soon as they had paid their adieux,

the word was given, the soldiers in thebateaux gave

three cheers, and away they went from the wharf into the stream. For a

short time there was waving of handkerchiefs and other tokens of

good-will on the part of those who were on the wharf; but that was soon

left behind them, and the family found themselves separated from their

acquaintances and silently listening to the measured sound of the oars,

as they dropped into the water.

And it is not to be wondered at that they were silent, for all were

occupied with their own thoughts. They called to mind the beautiful park

at Wexton, which they had quitted, after having resided there so long

and so happily; the hall, with all its splendour and all its comfort,

rose up in their remembrance; each room with its furniture, each window

with its view, was recalled to their memories; they had crossed the

Atlantic, and were now about to leave civilisation and comfort behind

them—to isolate themselves in the Canadian woods—to trust to their own

resources, their own society, and their own exertions. It was, indeed,

the commencement of a new life, and for which they felt themselves

little adapted, after the luxuries they had enjoyed in their former

condition; but if their thoughts and reminiscences made them grave and

silent, they did not make them despairing or repining; they trusted to

that Power who alone could protect—who gives and who takes away, and

doeth with us as He judges best; and if hope was not buoyant in all of

them, still there was confidence, resolution, and resignation. Gradually

they were roused from their reveries by the beauty of the scenery and

the novelty of what met their sight; the songs, also, of the Canadian

boatmen were musical and cheering, and by degrees, they had all

recovered their usual good spirits.

Alfred was the first to shake off his melancholy feelings and to attempt

to remove them from others; nor was he unsuccessful. The officer who

commanded the detachment of troops, and who was in the same bateaux with

the family, had respected their silence upon their departure from the

wharf—perhaps he felt as much as they did. His name was Sinclair, and

his rank that of senior captain in the regiment—a handsome, florid young

man, tall and well made, very gentleman-like, and very gentle in his

manners.

“How very beautiful the foliage is on that point, mother,” said Alfred,

first breaking the silence, “what a contrast between the leaves of the

sycamore, so transparent and yellow, with the sun behind them, and the

new shoots of the spruce fir.”

“It is indeed very lovely,” replied Mrs Campbell; “and the branches of

the trees, feathering down as they do to the surface of the water—”

“Like good Samaritans,” said Emma, “extending their arms, that any

unfortunate drowning person who was swept away by the stream might save

himself by their assistance.”

“I

had no idea that trees had so much charity or reflection, Emma,”

rejoined Alfred.

“I

cannot answer for their charity, but, by the side of this clear water,

you must allow them reflection, cousin,” replied Emma.

“I

presume you will add vanity to their attributes?” answered Alfred; “for

they certainly appear to be hanging over the stream that they may look

and admire themselves in the glassy mirror.”

“Pretty well that for a midshipman; I was not aware that they use such

choice language in a cockpit,” retorted the young lady.

“Perhaps not, cousin,” answered Alfred; “but when sailors are in the

company of ladies, they become refined, from the association.”

“Well, I must admit, Alfred, that you are a great deal more polished

after you have been a month on shore.”

“Thank you, cousin Emma, even for that slight admission,” replied Alfred

laughing.

“But what is that,” said Mary Percival, “at the point, is it a

village—one, two, three houses—just opening upon us?”

“That is a raft, Miss Percival, which is coming down the river,” replied

Captain Sinclair. “You will see when we are nearer to it, that perhaps

it covers two acres of water, and there are three tiers of timber on it.

These rafts are worth many thousand pounds. They are first framed with

logs, fastened by wooden tree-nails, and the timber placed within the

frame. There are, perhaps, from forty to a hundred people on this raft

to guide it down the stream, and the houses you see are built on it for

the accommodation of these people. I have seen as many as fifteen houses

upon a raft, which will sometimes contain the cargoes of thirty or forty

large ships.”

“It is very wonderful how they guide and direct it down the stream,”

said Mr Campbell.

“It is very dexterous; and it seems strange that such an enormous mass

can be so guided, but it is done, as you will perceive; there are three

or four rudders made of long sweeps, and as you may observe, several

sweeps on each side.”

All the party were now standing up in the stern-sheets of the bateaux to

look at the people on the raft, who amounted to about fifty or sixty

men—now running over the top to one side, and dragging at the sweeps,

which required the joint power of seven or eight men to each of them—now

passing again over to the opposite sweeps, as directed by the steersman.

The bateaux kept

well in to the shore, out of the way, and the raft passed them very

quickly. As soon as it was clear of the point, as their course to Quebec

was now straight, and there was a slight breeze down the river, the

people on board of the raft hoisted ten or fifteen sails upon different

masts, to assist them in their descent; and this again excited the

admiration of the party.

The conversation now became general, until the bateaux were

made fast to the shores of the river, while the men took their dinners,

which had been prepared for them before they left Quebec. After a repose

of two hours, they again started, and at nightfall arrived at Saint

Anne’s, where they found everything ready for their reception. Although

their beds were composed of the leaves of the maize or Indian corn, they

were so tired that they found them very comfortable, and at daylight

arose quite refreshed, and anxious to continue their route. Martin

Super, who, with the two youngest boys, had been placed in a separate

boat, had been very attentive to the comforts of the ladies after the

debarkation; and it appeared that he had quite won the hearts of the two

boys by his amusing anecdotes during the day.

Soon after their embarkation, the name of Pontiac being again mentioned

by Captain Sinclair, Mrs Campbell observed—

“Our man Super mentioned that name before. I confess that I do not know

anything of Canadian affairs; I know only that Pontiac was an Indian

chief. Can you, Captain Sinclair, give us any information relative to a

person who appears so well known in the province?”

“I

shall be happy, Mrs Campbell, as far as I am able, to satisfy you. On

one point, I can certainly speak with confidence, as my uncle was one of

the detachment in the fort of Detroit at the time that it was so nearly

surprised, and he has often told the history of the affair in my

presence. Pontiac was chief of all the Lake tribes of Indians. I will

not repeat the names of the different tribes, but his own particular

tribe was that of the Ottawas. He ruled at the time that the Canadas

were surrendered to us by the French. At first, although very proud and

haughty, and claiming the sovereignty of the country, he was very civil

to the English, or, at least, appeared so to be; for the French had

given us so bad a reputation with all the northern tribes, that they had

hitherto shown nothing but the most determined hostility, and appeared

to hate our very name. They are now inclined to quiet, and it is to be

hoped their fear of us, after the several conflicts between us, will

induce them to remain so. You are, perhaps, aware that the French had

built many forts at the most commanding spots in the interior and on the

lakes, all of which, when they gave up the country, were garrisoned by

our troops, to keep the Indians under control.

“All these forts are isolated, and communication between them is rare.

It was in 1763 that Pontiac first showed his hostility against us, and

his determination, if possible, to drive us from the lakes. He was as

cunning as he was brave; and, as an Indian, showed more generalship than

might be expected—that is, according to their system of war, which is

always based upon stratagem. His plan of operation was, to surprise all

our forts at the same time, if he possibly could; and so excellent were

his arrangements, that it was only fifteen days after the plan was first

laid, that he succeeded in gaining possession of all but three; that is,

he surprised ten out of thirteen forts. Of course, the attacks were made

by other chiefs, under his directions, as Pontiac could not be at all

the simultaneous assaults.”

“Did he murder the garrisons, Captain Sinclair?” said Alfred.

“The major portion of them: some were spared, and afterwards ransomed at

high prices. I ought to have mentioned, as a singular instance of the

advance of this chief in comparison with the other Indians, that at this

time he issued bills of credit on slips of bark, signed with his totem,

the otter; and that these bills, unlike many of more civilised society,

were all taken up and paid.”

“That is very remarkable in a savage,” observed Mrs Campbell; “but how

did Pontiac contrive to surprise all the forts?”

“Almost the whole of them were taken by a singular stratagem. The

Indians are very partial to, and exceedingly dexterous at, a game called

the ‘Baggatiway’: it is played with a ball and a long-handled sort of

racket. They divide into two parties, and the object of each party is to

drive the hall to their own goal. It is something like hurly in England,

or golf in Scotland. Many hundreds are sometimes engaged on both sides;

and the Europeans are so fond of seeing the activity and dexterity shown

by the Indians at this game, that it was very common to request them to

play it, when they happened to be near the forts. Upon this, Pontiac

arranged his plan, which was that his Indians should commence the game

of ball under the forts, and after playing a short time, strike the ball

into the fort: of course, some of them would go in for it; and having

done this two or three times, and recommenced the play to avoid

suspicion, they were to strike it over again, and follow it up by a rush

after it through the gates; and then, when they were all in, they would

draw their concealed weapons, and overpower the unsuspicious garrison.”

“It was, certainly, a very ingenious stratagem,” observed Mrs Campbell.

“And it succeeded, as I have observed, except on three forts. The one

which Pontiac directed the attack upon himself, and which was that which

he was most anxious to obtain, was Detroit, in which, as I have before

observed, my uncle was garrisoned; but there he failed, and by a

singular circumstance.”

“Pray tell us how, Captain Sinclair,” said Emma; “you don’t know how

much you have interested me.”

“And me, too, Captain Sinclair,” continued Mary.

“I

am very happy that I have been able to wear away any portion of your

tedious journey, Miss Percival, so I shall proceed with my history.

“The fort of Detroit was garrisoned by about three hundred men, when

Pontiac arrived there with a large force of Indians, and encamped under

the walls; but he had his warriors so mixed up with the women and

children, and brought so many articles for trade, that no suspicion was

created. The garrison had not heard of the capture of the other forts

which had already taken place. At the same time the unusual number of

the Indians was pointed out to Major Gladwin, who commanded the fort,

but he had no suspicions. Pontiac sent word to the major, that he wished

to ‘have a talk’ with him, in order to cement more fully the friendship

between the Indians and the English; and to this Major Gladwin

consented, appointing the next day to receive Pontiac and his chiefs in

the fort.

“Now it so happened, that Major Gladwin had employed an Indian woman to

make him a pair of mocassins out of a very curiously marked elk-skin.

The Indian woman brought him the mocassins with the remainder of the

skin. The major was so pleased with them, that he ordered her to make

him a second pair of mocassins out of the skin, and then told her that

she might keep the remainder for herself. The woman having received the

order, quitted the major; but instead of leaving the fort, remained

loitering about till she was observed, and they inquired why she did not

go. She replied, that she wanted to return the rest of the skin, as he

set so great a value on it; and as this appeared strange conduct, she

was questioned, and then she said, that if she took away the skin then,

she never would be able to return it.

“Major Gladwin sent for the woman, upon hearing of the expressions which

she had used, and it was evident that she wanted to communicate

something, but was afraid; but on being pressed hard and encouraged, and

assured of protection, she then informed Major Gladwin, that Pontiac and

his chiefs were to come into the fort to-morrow, under the plea of

holding a talk; but that they had cut the barrels of their rifles short,

to conceal them under their blankets, and that it was their intention,

at a signal given by Pontiac, to murder Major Gladwin and all his

officers who were at the council; while the other warriors, who would

also come into the fort with concealed arms, under pretence of trading,

would attack the garrison outside.

“Having obtained this information, Major Gladwin did all he could to put

the fort into a state of defence, and took every necessary precaution.

He made known to the officers and men what the intentions of the Indians

were, and instructed the officers how to act at the council, and the

garrison how to meet the pretended traders outside.

“About ten o’clock, Pontiac and his thirty-six chiefs, with a train of

warriors, came into the fort to their pretended council, and were

received with great politeness. Pontiac made his speech, and when he

came forward to present the wampum belt, the receipt of which by the

major was, as the Indian woman had informed them, to be the signal for

the chiefs and warriors to commence the assault, the major and his

officers drew their swords half out of their scabbards, and the troops,

with their muskets loaded and bayonets fixed, appeared outside and in

the council-room, all ready to present. Pontiac, brave as he really was,

turned pale: he perceived that he was discovered, and consequently, to

avoid any open detection, he finished his speech with many professions

of regard for the English. Major Gladwin then rose to reply to him, and

immediately informed him that he was aware of his plot and his murderous

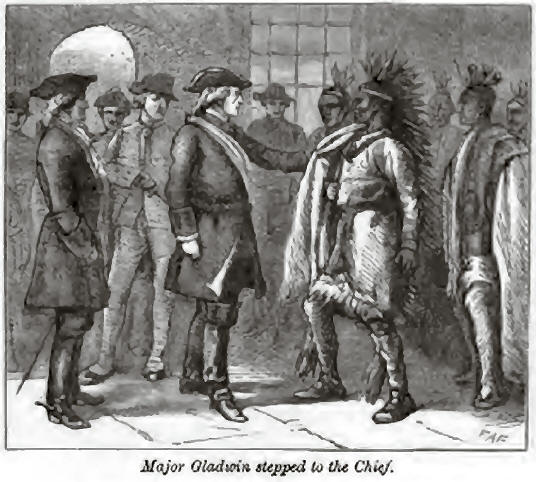

intentions. Pontiac denied it; but Major Gladwin stepped to the chief,

and drawing aside his blanket, exposed his rifle cut short, which left

Pontiac and his chiefs without a word to say in reply. Major Gladwin

then desired Pontiac to quit the fort immediately, as otherwise he

should not be able to restrain the indignation of the soldiers, who

would immolate him and all his followers who were outside the fort.

Pontiac and his chiefs did not wait for a second intimation, but made

all the haste they could to get outside of the gates.”

“Was it prudent in Major Gladwin to allow Pontiac and his chiefs to

leave, after they had come into the fort with an intent to murder him

and his men?” said Henry Campbell. “Would not the major have been

justified in detaining them?”

“I

certainly think he would have been, and so did my uncle, but Major

Gladwin thought otherwise. He said that he had promised safe conduct and

protection to and from the fort before he was aware of the conspiracy;

and, having made a promise, his honour would not allow him to depart

from it.”

“At all events, the major, if he erred, erred on the right side,”

observed Alfred. “I think myself that he was too scrupulous, and that I

in his place should have detained some of them, if not Pontiac himself,

as a hostage for the good behaviour of the rest of the tribes.”

“The result proved that if Major Gladwin had done so, he would have done

wisely; for the next day Pontiac, not at all disarmed by Major Gladwin’s

clemency, made a furious attack upon the fort. Every stratagem was

resorted to, but the attack failed. Pontiac then invested it, cut off

all their supplies, and the garrison was reduced to great distress. But

I must break off now, for here we are at Trois Rivières, where we shall

remain for the night. I hope you will not find your accommodation very

uncomfortable, Mrs Campbell: I fear as we advance you will have to put

up with worse.”

“And we are fully prepared for it, Captain Sinclair,” replied Mr

Campbell; “but my wife and my nieces have too much good sense to expect

London hotels in the wilds of Canada.”

The bateaux were

now on shore, and the party landed to pass the night at the small

stockaded village of Trois Rivières.