It may appear strange that, after having been in

possession of the estate for ten years, and considering that he had

younger children to provide for, Mr Campbell had not laid up a larger

sum; but this can be fully explained.

As

I before said, the estate was in very bad order when Mr Campbell came

into possession, and he devoted a large portion of the income to

improving it; and, secondly, he had expended a considerable sum in

building almshouses and schools, works which he would not delay, as he

considered them as religious obligations. The consequence was, that it

was not until a year before the claim was made to the estate that he had

commenced laying by for his younger children; and as the estate was then

worth 2,000 pounds per annum more than it was at the time that he came

into possession of it, he had resolved to put by 5,000 pounds per annum,

and had done so for twelve months. The enormous legal expenses had,

however, swallowed up this sum, and more, as we have already stated; and

thus he was left a poorer man by some hundreds than he was when the

property fell to him. The day after the valuation the eldest son, Henry,

made his appearance; he seemed much dejected, more so than his parents,

and those who knew him, would have supposed. It was, however, ascribed

to his feeling for his father and mother, rather than for himself.

Many were the consultations held by Mr and Mrs Campbell as to their

future plans; but nothing at all feasible, or likely to prove

advantageous, suggested itself to them. With only sixteen or seventeen

hundred pounds, they scarcely knew where to go or how to act. Return to

his profession Mr Campbell knew that he could not, with any chance of

supporting his family. His eldest son, Henry, might obtain a situation,

but he was really fit for nothing but the bar or holy orders; and how

were they to support him till he could support himself? Alfred, who was

now a master’s mate, could, it is true, support himself, but it would be

with difficulty, and there was little chance of his promotion. Then

there were the two other boys, and the two girls growing up fast; in

short, a family of eight people. To put so small a sum in the funds

would be useless, as they could not live upon the interest which it

would give, and how to employ it they knew not. They canvassed the

matter over and over, but without success, and each night they laid

their heads upon the pillow more and more disheartened. They were all

ready to leave the Hall, but knew not where to direct their steps when

they left it; and thus they continued wavering for a week, until they

were embraced by their son Alfred, who had made all speed to join them

as soon as the ship had been paid off. After the first joy of meeting

between those who had been separated so long was over, Mr Campbell said,

“I’m sorry, Alfred, that I could not give your messmates any fishing.”

“And so am I, and so were they, for your sakes, my dear father and

mother; but what is, is—and what can’t be helped, can’t—so we must make

the best of it; but where’s Henry and my cousins?”

“They are walking in the park, Alfred: you had better join them; they

are most anxious to see you.”

“I

will, mother; let us get over these huggings and kissings, and then we

shall be more rational: so good-bye for half an hour,” said Alfred,

kissing his mother again, and then hastening out of the room.

“His spirits are not subdued, at all events,” observed Mrs Campbell. “I

thank God for it.”

Alfred soon fell in with his brother and his cousins, Mary and Emma, and

after the huggings and kissings, as he termed them, were over, he made

inquiries into the real state of his father’s affairs. After a short

conversation, Henry, who was very much depressed in his spirits, said,

“Mary and Emma, perhaps you will now go in; I wish to have some

conversation with Alfred.”

“You are terribly out of heart, Harry,” observed Alfred, after his

cousins had left them. “Are things so very bad?”

“They are bad enough, Alfred; but what makes me so low-spirited is, that

I fear my folly has made them worse.”

“How so?” replied Alfred.

“The fact is, that my father has but 1,700 pounds left in the world, a

sum small enough; but what annoys me is this. When I was at college,

little imagining such a reverse of fortune, I anticipated my allowance,

because I knew I could pay at Christmas, and I ran in debt about 200

pounds. My father always cautioned me not to exceed my allowance, and

thinks that I have not done so. Now, I cannot bear the idea of leaving

college in debt, and, at the same time, it will be a heavy blow to my

poor father, if he has to part with 200 pounds, out of his trifling

remainder, to pay my debt. This is what has made me so unhappy. I cannot

bear to tell him, because I feel convinced that he is so honourable, he

will pay it immediately. I am mad with myself, and really do not know

what to do. I do nothing but reproach myself all day, and I cannot sleep

at night. I have been very foolish, but I am sure you will kindly enter

into my present feelings. I waited till you came home, because I thought

you had better tell my father the fact, for I feel as if I should die

with shame and vexation.”

“Look you, Harry,” replied Alfred, “as for outrunning the constable, as

we term it at sea, it’s a very common thing, and, all things considered,

no great harm done, when you suppose that you have the means, and intend

to pay; so don’t lay that to heart. That you would give your right hand

not to have done so, as things have turned out, I really believe; but,

however, there is no occasion to fret any more about it, I have received

three years’ pay, and the prize-money for the last eighteen months, and

there is still some more due, for a French privateer. Altogether it

amounts to 250 pounds, which I had intended to have made over to my

father, now that he is on a lee-shore; but it will come to the same

thing, whether I give it to you to pay your debts, or give it to him, as

he will pay them, if you do not; so here it is, take what you want, and

hand me over what’s left. My father don’t know that I have any money,

and now he won’t know it; at the same time he won’t know that you owe

any; so that squares the account, and he will be as well off as ever.”

“Thank you, my dear Alfred; you don’t know what a relief this will be to

my mind. Now I can look my father in his face.”

“I

hope you will; we are not troubled with such delicate feelings on board

ship, Harry. I should have told him the truth long before this. I

couldn’t bear to keep anything on my conscience. If this misfortune had

happened last cruise, I should have been just in your position; for I

had a tailor’s bill to pay as long as a frigate’s pennant, and not

enough in my pocket to buy a mouse’s breakfast. Now, let us go in again

and be as merry as possible, and cheer them up a little.”

Alfred’s high spirits did certainly do much to cheer them all up; and

after tea, Mr Campbell, who had previously consulted his wife, as soon

as the servant had quitted the room, entered on a full explanation of

the means which were left to them; and stated that he wished in his

difficulty to put the question before the whole family, and ascertain

whether any project might come into their heads upon which they might

decide and act. Henry, who had recovered his spirits since the

assistance he had received from Alfred, was desired to speak first. He

replied:

“My dear father and mother, if you cannot between you hit upon any plan,

I am afraid it is not likely that I can assist you. All I have to say

is, that whatever may be decided upon, I shall most cheerfully do my

duty towards you and my brothers and sisters. My education has not been

one likely to be very useful to a poor man, but I am ready to work with

my hands as well as with my head to the best of my abilities.”

“That I am sure of, my dear boy,” replied his father.

“Now, Alfred, we must look to you as our last hope, for your two cousins

are not likely to give us much advice.”

“Well, father, I have been thinking a good deal about it, and I have a

proposal to make which may at first startle you, but it appears to me

that it is our only, and our best resource. The few hundred pounds which

you have left are of no use in this country, except to keep you from

starving for a year or two; but in another country they may be made to

be worth as many thousands. In this country, a large family becomes a

heavy charge and expense; in another country, the more children you

have, the richer man you are. If, therefore, you would consent to

transport your family and your present means into another country,

instead of being a poor, you might be a rich man.”

“What country is that, Alfred?”

“Why, father, the purser of our ship had a brother, who, soon after the

French were beaten out of the Canadas, went out there to try his

fortune. He had only three hundred pounds in the world; he has been

there now about four years, and I read a letter from him which the

purser received when the frigate arrived at Portsmouth, in which he

states that he is doing well, and getting rich fast; that he has a farm

of five hundred acres, of which two hundred are cleared; and that if he

only had some children large enough to help him, he would soon be worth

ten times the money, as he would purchase more land immediately. Land is

to be bought there at a dollar an acre, and you may pick and choose.

With your money, you might buy a large property; with your children, you

might improve it fast; and in a few years, you would, at all events, be

comfortable, if not flourishing, in your circumstances. Your children

would work for you, and you would have the satisfaction of knowing that

you left them independent and happy.”

“I

acknowledge, my dear boy, that you have struck upon a plan which has

much to recommend it. Still there are drawbacks.”

“Drawbacks!” replied Alfred; “yes, to be sure there are. If estates were

to be picked up for merely going out for them, there would not be many

left for you to choose; but, my dear father, I know no drawbacks which

cannot be surmounted. Let us see what these drawbacks are. First, hard

labour; occasional privation; a log-hut, till we can get a better;

severe winter; isolation from the world; occasional danger, even from

wild beasts and savages. I grant these are but sorry exchanges for such

a splendid mansion as this—fine furniture, excellent cooking, polished

society, and the interest one feels for what is going on in our own

country, which is daily communicated to us. Now, as to hard labour, I

and Henry will take as much of that off your hands as we can; if the

winter is severe, there is no want of firewood; if the cabin is rude, at

least we will make it comfortable; if we are shut out from the world, we

shall have society enough among ourselves; if we are in danger, we will

have firearms and stout hearts to defend ourselves; and, really, I do

not see but we may be very happy, very comfortable, and, at all events,

very independent.”

“Alfred, you talk as if you were going with us,” said Mrs Campbell.

“And do you think that I am not, my dear mother? Do you imagine that I

would remain here when you were there, and my presence would be useful?

No, no! I love the service, it is true, but I know my duty, which is, to

assist my father and mother: in fact, I prefer it; a midshipman’s ideas

of independence are very great—and I had rather range the wilds of

America free and independent than remain in the service and have to

touch my hat to every junior lieutenant, perhaps for twenty years to

come. If you go, I go, that is certain. Why, I should be miserable if

you went without me; I should dream every night that an Indian had run

away with Mary, or that a bear had eaten up my little Emma.”

“Well, I’ll take my chance of the Indian,” replied Mary Percival.

“And I of the bear,” said Emma. “Perhaps he’ll only hug me as tight as

Alfred did when he came home.”

“Thank you, Miss, for the comparison,” replied Alfred, laughing.

“I

certainly consider that your proposal, Alfred, merits due reflection,”

observed Mrs Campbell. “Your father and I will consult, and perhaps by

to-morrow morning we may have come to a decision. Now we had better all

go to bed.”

“I

shall dream of the Indian, I am sure,” said Mary.

“And I shall dream of the bear,” added Emma, looking archly at Alfred.

“And I shall dream of a very pretty girl that I saw at Portsmouth,” said

Alfred.

“I

don’t believe you,” replied Emma.

Shortly afterwards Mr Campbell rang the bell for the servants; family

prayers were read, and all retired in good spirits.

The next morning they all met at an early hour; and after Mr Campbell

had, as was his invariable rule, read a portion of the Bible, and a

prayer of thankfulness, they sat down to breakfast. After breakfast was

over, Mr Campbell said—

“My dear children, last night, after you had left us, your mother and I

had a long consultation, and we have decided that we have no alternative

left us but to follow the advice which Alfred has given; if, then, you

are all of the same opinion as we are, we have resolved that we will try

our fortunes in the Canadas.”

“I

am certainly of that opinion,” replied Henry.

“And you, my girls?” said Mr Campbell.

“We will follow you to the end of the world, uncle,” replied Mary, “and

try if we can by any means in our power repay your kindness to two poor

orphans.”

Mr

and Mrs Campbell embraced their nieces, for they were much affected by

Mary’s reply.

After a pause, Mrs Campbell said—

“Now that we have come to a decision, we must commence our arrangements

immediately. How shall we dispose of ourselves? Come, Alfred and Henry,

what do you propose doing?”

“I

must return immediately to Oxford, to settle my affairs, and dispose of

my books and other property.”

“Shall you have sufficient money, my dear boy, to pay everything?” said

Mr Campbell.

“Yes, my dear father,” replied Henry, colouring up a little.

“And I,” said Alfred, “presume that I can be of no use hers; therefore I

propose that I should start for Liverpool this afternoon by the coach,

for it is from Liverpool that we had better embark. I shall first write

to our purser for what information he can procure, and obtain all I can

at Liverpool from other people. As soon as I have anything to

communicate, I will write.”

“Write as soon as you arrive, Alfred, whether you have anything to

communicate or not; at all events, we shall know of your safe arrival.”

“I

will, my dear mother.”

“Have you money, Alfred?”

“Yes, quite sufficient, father. I don’t travel with four horses.”

“Well, then, we will remain here to pack up, Alfred; and you must look

out for some moderate lodgings for us to go into as soon as we arrive at

Liverpool. At what time do the ships sail for Quebec?”

“Just about this time, father. This is March, and they will now sail

every week almost. The sooner we are off the better, that we may be

comfortably housed in before the winter.”

A

few hours after this conversation, Henry and Alfred left the Hall upon

their several destinations. Mr and Mrs Campbell and the two girls had

plenty of employment for three or four days in packing up. It was soon

spread through the neighbourhood that they were going to emigrate to

Canada; and the tenants who had held their farms under Mr Campbell, all

came forward and proffered their waggons and horses to transport his

effects to Liverpool, without his being put to any expense.

In

the meantime a letter had been received from Alfred, who had not been

idle. He had made acquaintance with some merchants who traded to Canada,

and by them had been introduced to two or three persons who had settled

there a few years before, and who were able to give him every

information. They informed him what was most advisable to take out; how

they were to proceed upon their landing; and what was of more

importance, the merchants gave him letters of introduction to English

merchants at Quebec, who would afford them every assistance in the

selecting and purchasing of land, and in their transport up the country.

Alfred had also examined a fine timber-ship, which was to sail in three

weeks; and had bargained for the price of their passage, in case they

could get ready in time to go by her. He wrote all these particulars to

his father, waiting for his reply to act upon his wishes.

Henry returned from Oxford, having settled his accounts, and with the

produce of the sale of his classics and the other books in his pocket.

He was full of spirits, and of the greatest assistance to his father and

mother.

Alfred had shown so much judgment in all he had undertaken, that his

father wrote to him stating that they would be ready for the ship which

he named, and that he might engage the cabins, and also at once procure

the various articles which they were advised to take out with them, and

draw upon him for the amount, if the people would not wait for the

money. In a fortnight they were all ready; the waggons had left with

their effects some days before. Mr Campbell wrote a letter to Mr Douglas

Campbell, thanking him for his kindness and consideration to them, and

informing him that they should leave Wexton Hall on the following day.

He only begged, as a favour, that the schoolmaster and schoolmistress of

the village school should be continued on, as it was of great importance

that the instruction of the poor should not be neglected; and added,

that perceiving by the newspapers that Mr Douglas Campbell had lately

married, Mrs Campbell and he wished him and his wife every happiness,

etcetera, etcetera.

Having despatched this letter, there was nothing more to be done,

previous to their departure from the Hall, except to pay and dismiss the

few servants who were with them—for Mrs Campbell had resolved upon

taking none, out with her.

That afternoon they walked round the plantation and park for the last

time. Mrs Campbell and the girls went round the rooms of the Hall to

ascertain that everything was left tidy, neat, and clean. The poor girls

sighed as they passed by the harp and piano in the drawing-room, for

they were old friends.

“Never mind, Mary,” said Emma; “we have our guitars, and may have music

in the woods of Canada without harp or piano.”

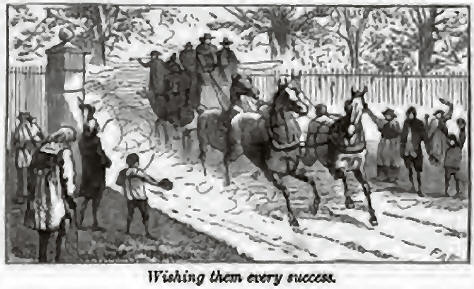

The following morning, the coach, of which they had secured the whole of

the inside, drove up to the Hall door, and they all got in, the tenants

and poor people standing round them, all with their hats in their hands

out of respect, and wishing them every success as they drove away

through the avenue to the park gates. The Hall and the park itself had

been long out of sight before a word was exchanged.

They checked their tears, but their hearts were too full for them to

venture to speak.

The day afterwards they arrived at Liverpool, where Alfred had provided

lodgings. Everything had been sent on board, and the ship had hauled out

in the stream. As they had nothing to detain them on shore, and the

captain wished to take advantage of the first fair wind, they all

embarked, four days after their arrival at Liverpool; and I shall now

leave them on board of the London

Merchant, which was the name of the vessel, making all their little

arrangements previous to their sailing, under the superintendence of

Alfred, while I give some little more insight into the characters, ages,

and dispositions of the family.