|

“Now children,” said Mrs.

Morelle, while she and the children were at breakfast, "since we are

safe on shore, we can begin to talk about our plans. It is now about the

middle of June. Mr. Morelle will not arrive in London until September.

So that we have two months and a half to spend in rambling about. And

the question is where we shall go.”

“You must decide that mother,” said Florence,

“Yes,” replied Mrs. Morelle, “I will decide it, but first I wish to hear

what you all have to say about it. You may all propose the plans which

you would prefer, and then I will take the subject into consideration

and decide.”

The children then all began to talk about the different tours which they

had heard the passengers speak of on board the ship, toward the end of

the voyage, when they had become well enough to tak6 out their maps and

guide-books, and to consult together about the tours which they were to

make. Florence said that there was a beautiful region called the lake

country, full of mountains and lakes, which lay to the north of

Liverpool, in the counties of Cumberland and Westmoreland. The Isle of

Wight was proposed too, which is a very charming island lying off the

southern coast of England, and a great place of resort for parties

travelling for health or pleasure.

John said that for his part he would like to go directly to Paris. His

motive for this was partly the long and rapid journey by railway and

steamboat which it would require, but chiefly because he wished to see

the performances at the Hippodrome, a famous place in Paris for

equestrian shows, of which he had heard very glowing accounts before he

left America.

When it came to Grimkie's turn to propose a plan, he said that what he

should like best, if he thought that his aunt and Florence would like

it, would be to go to the Orkney Islands.

“To the Orkney Islands!" exclaimed Mrs. Morelle in a tone of surprise;

"why they are beyond the very northern extremity of Scotland."

“Yes, Auntie, I know they are," said Grimkie; “that is the reason why I

want to go and see them."

Mrs. Morelle paused a moment, and seemed to be thinking.

“Florence,” said she, at length, “go into our bedroom and get my little

atlas. You will find it on the table there. I took it out of the trunk

this morning.

Mrs. Morelle always carried a small atlas with her, especially when

travelling with the children, for she found that occasions were

continually arising in which it was necessary, or at least very

desirable, to refer to the map.

Florence went out, and in a few minutes returned bringing the atlas with

her.

Mrs. Morelle took the atlas and opened it at the map of Scotland. After

examining the map attentively, she turned to the map of North America.

“The Orkney Islands extend as far up as latitude fifty-nine and a half,”

said she, “and the lower point of Greenland is only sixty. So that you

would take us to within half a degree of the latitude of Greenland.”

“Yes, Auntie,” said Grimkie, “that is just it. To think that we can go

so far north as that and have good roads and good comfortable inns all

the way.”

“But we should have to go a part of the way by sea,” said Mrs. Morelle.

“The Orkneys are islands at some distance from the main land.”

“Only six miles, Auntie,” said Grimkie. “It is only across the Pentland

Firth, and that is only six miles wide.”

“But are not the seas in that region very stormy?” .

“Yes, Auntie,” said Grimkie, “they are the stormiest seas in the world.

Those are the seas that the old Norsemen used to navigate, between the

coasts of Norway and Scotland, and the Orkney and Shetland Islands and

Iceland. The Norsemen were the greatest sailors in the world. They lived

almost always on the water, and the harder it blew the better they liked

it. I want to go and see where they used to sail.”

Grimkie had recently been studying history at the Chateau, and it was

there that he had learned about the wonderful exploits which those old

sea kings, as they were sometimes called, used to perform in the ships

in which they navigated these stormy northern seas. They were very rude

and violent men, and they seemed to consider that they had a right to

everything that they could find, no matter where, provided they were

strong enough to take it. The richest or the most daring among them, who

found means to build or buy one or more vessels, would enlist a party of

followers, and with this horde make descents upon any of the coasts in

all those regions, and plunder the people of their cattle, or seize

their little town. Sometimes they would take possession of certain

places on the coast and make agreements with the people living there,

that if they would give them a certain portion of their cattle every

year, they would protect them from any other marauders who might come to

rob them. This the people would consent to do, and thus the foundation

was laid for territorial governments, on the different coasts adjoining

these northern seas.

In process of time the Norsemen and their descendants extended their

incursions not only to the islands north of Scotland and to Scotland

itself, but also to the coasts of England and Ireland, and at last even

of France, where they settled a country, which, from their occupancy of

it, received the name of Normandy, which name it retains to the present

day.

It was among these rude men, and in these boisterous and terrible seas,

where a dismal twilight reigns almost supreme for half the year, and

winds and fogs and ice, and sweeping and impetuous tides, have almost

continual possession of the sea, that the progenitors of the present

race of British and American seamen had their origin. The case is often

referred to in history, as affording a conspicuous illustration of the

effect which the encountering of difficulty and danger produces, in

stimulating the exertions of men, and developing the highest capacities

of their nature.

“There is another reason," said Grimkie, “why I should like to go now to

the Orkney Islands, and that is because it is so near the summer

solstice. I have a great desire to get as far north as I can in the time

of the summer solstice. Even here the sun rises now between three and

four, and it is quite light at two. In the Orkneys there can scarcely be

any night at all."

Grimkie it seems had been studying astronomy as well as history, at the

Chateau, and so he was quite learned about the summer solstice and other

such things. It may be well, however, for me to explain, for the sake of

the younger portion of my readers, that the phrase summer solstice

refers, for the northern hemisphere, to that portion of the year, when

the sun, in his apparent motion, comes farthest to the north, as the

winter solstice relates to that portion of the year when the sun

declines farthest to the south.

The summer solstice occurs on the twenty-first or twenty-second of June,

and the winter solstice on the twenty-first or twenty-second of

December.

In the summer solstice the days are longest and the nights shortest. In

the winter solstice the days are shortest and the nights longest— that

is, to all people living in northern latitudes.

Now it is a very curious circumstance, the cause of which it would be

somewhat difficult to explain without showing it by means of a globe,

that the difference in length between the days and the nights increases

greatly the farther north we go. On or near the equator the difference

is very little, at any part of the year. The days throughout the whole

year are very nearly twelve hours long, and the nights too. At the pole,

however, if it were possible for any one to reach the pole, the day

would continue during the whole twenty-four hours for six months in the

year, and then the night would continue through the whole twenty-four

hours during the remaining six months. In the latitude of the southern

part of Greenland, the days, at the time of the summer solstice, are

more than eighteen hours long, and the nights not quite six.

There is another remarkable phenomenon too, to be observed in high

northern latitudes, in the time of the summer solstice, which Grimkie

was very desirous of verifying by his own observation, and that is the

long continuance of the twilight, and the very early appearance of the

dawn. The reason of this is that the path of the sun is so oblique to

the horizon, or in other words the sun goes down in so slanting a

direction, that it is a long time after sunset before he gets low enough

to withdraw his light entirely from view.

“I should think,” said Grimkie, “that in the Orkney Islands it would be

light nearly all night. The sun does not set there now till after nine

o’clock, and it rises again before three, and so I should think the

twilight would not be over before the dawn would begin. And I want to go

and see if it really is so.”

“It would be very curious indeed,” said Florence, “to have it light all

night, and no moon I should like to see it myself, if it really is so."

“But then,” she added, after a pause, “we should have to sit up all

night to see it.”

“No,” said Grrimkie. “We might get up from time to time, and look out

the window. Or perhaps we might be travelling all night somewhere, and

then we should see it.”

After some farther conversation, Mrs. Morelle said that she would not

decide at once in respect to Grimkie’s plan, but would wait until she

had obtained some farther information.

“Or rather,” she said, “until you have obtained some farther information

for me. After breakfast you may go to a bookstore and buy a good

travelling map of Scotland, and also a railway guide. Florence and John

may go with you, if they please. Then some time during the day you may

study out the different ways of going, and see which you think is the

best way. You must find out where the steamer sails from too, to take us

across the six miles of water. Then at dinner to-day you can tell me

what you have found out, and show me by the map, exactly which way we

shall have to go, and what sort of conveyances we shall have for the

different portions of the journey. Then when I have all the facts before

me I can decide.”

Grimkie accordingly bought the map and the guide book, and he spent more

than two hours that day in studying them so as to make himself as

thoroughly acquainted as possible with every thing pertaining to the

route. Mrs. Morelle did not assist him in these researches. In fact she

was out shopping during most of the time while Grimkie was making them.

Besides she thought it best to leave him to investigate the case as well

as he could himself, in the first instance, without any aid.

Accordingly, when the party were assembled for dinner that day,,and just

before the waiter brought the dinner in, Mrs. Morelle asked Grimkie what

sort of report he had to make about the way of reaching the Orkney

Islands.

“I have some bad news for you, in the first place,” said Grimkie. "We

shall have a great deal more than six miles to go in a steamer.” "How is

that?” asked Mrs. Morelle.

“Because there is no steamer that goes across in the shortest place,”

said Grimkie. “There is a sail boat that goes that way, to take the

mails, but we could not go in the sail boat very well. The only large

steamer is one that goes from Edinburgh. The only places where it stops

are Aberdeen and Wick. Wick is the last place it touches at. And from

Wick to Kirkwall, which is the town where we land in the Orkneys, it is

about sixty miles. So that we should have a steamer voyage of five or

six hours to take.” "That is bad news indeed,” said Mrs. Morelle. "But

then there is one thing favorable about it,” continued Grimkie, “and

that is that there is only six miles of the voyage that is in an open

sea. We should be sheltered by the land on one side all the way,

excepting for about six miles We might at any rate go as far as Wick;

and then see how the weather is. If the sea is smooth and calm, then we

might go on board the steamer. If not we might wait for the next steamer

or give it up altogether. All the way from here to Wick there will he no

difficulty. It will be a very pleasant journey.”

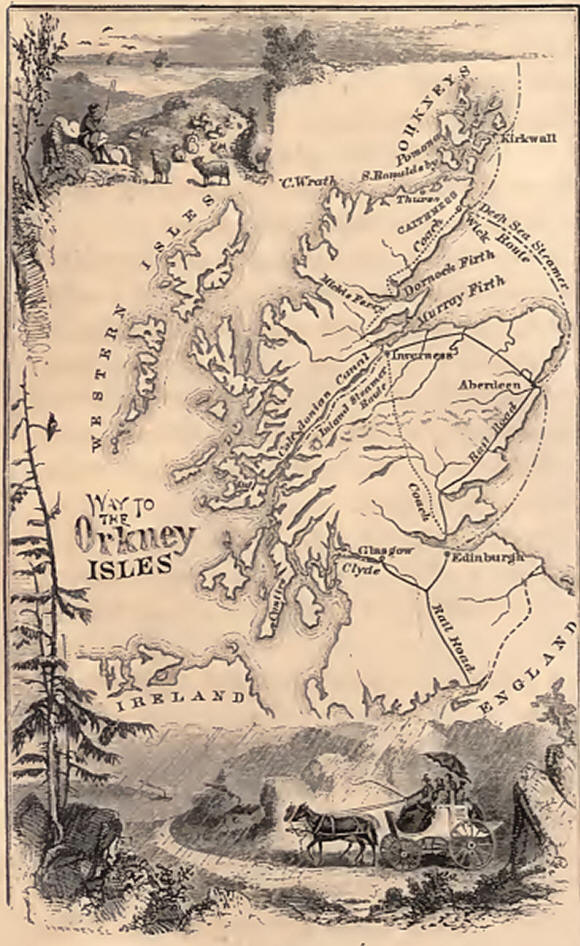

Grimkie then unfolded his map in order to

explain to his aunt the general features of the country so far as they

affected the different modes of travelling to the north of Scotland.

“Here is Wick,” said Grimkie, pointing to the situation of that town on

the northwest coast of Scotland. It lies as the reader will see by the

map, north of a great bay formed by the union of Murray and Dornock

Firths. Grimkie pointed out the situation of Wick and also that of

Inverness, which lies in the bottom of the bay, at the head of Murray

Firth.

“The steamer,” he says, “sails from Edinburgh once a week. She touches

at Aberdeen, for that is directly in her way, on the eastern coast.”

Here Grimkie pointed out the situation of Aberdeen.

“But she does not go to Inverness,” continued Grimkie, “although that is

a very large and important town, because that would take her too much

out of her way. So she steers right across the mouth of the bay, where

she must be in the open sea for some time, and makes for Wick. There she

takes in freight and passengers, and then sails again north along the

coast to the Orkney Islands. The town where she stops in the Orkneys is

Kirkwall. After that she sails on and goes to the Shetland Islands,

fifty or sixty miles farther over the open sea.”

“But Grimkie,” said Mrs. Morelle, “why did not you propose to go to the

Shetland Islands instead of the Orkneys, while you were about it? You

would be still more among the Norsemen's seas there, and the nights

would be still shorter.”

“Ah!” said Grimkie, “that was my discretion, Auntie. I should like very

much to go on to the end of the route, and to see the Shetland ponies,

but I knew that you and Florence would not like so long a voyage, and so

I only proposed going to the Orkneys.”

“That was discretion indeed,” said Mrs. Morelle. “But tell us the rest

of the plan. How about getting to Wick?”

“The next stage this side of Wick,” said Grimkie, “is Inverness. From

Inverness to Wick we should go by stage-coach. That we should all like.

You said the other day, on board ship, that you would like one more good

ride in an English stage-coach, and here is an excellent chance. The

road winds in and out to pass round the locks and firths, and then

coasts along the sea delightfully. At least so my guide book says. There

is one splendid pass which it goes through, equal to Switzerland.”

“I should like that very much,” said Mrs. Morelle. “And now how about

getting to Inverness?” ,

“There are three ways,” said Grimkie. “We can go by the railroads on the

eastern side of the island, or by coaches and posting up through the

center, or by inland steam navigation on the western side.”

Grimkie then went on to explain what he had learned by long study of the

maps and guide books during the day. The information which he

communicated was substantially as follows: The western part of Scotland

north of Glasgow is so mountainous, and so intersected in every

direction with long and narrow bays setting in from the sea, and also

with inland lakes, that no railroad can well be made there. By

connecting these lakes, however, and by cutting across one or two narrow

necks of land, and making canals and locks along the sides of some rapid

rivers, a channel of inland navigation has been opened, by which

steamers can pass all the way from Glasgow to Inverness, through the

very heart of the country. The route of the steamers in taking this

voyage, for some portion of the way, lies along the shore of the sea,

but it is in places where the water is so sheltered by islands and by

lofty promontories and headlands, that the ocean swell has very little

access to it in any part of the way.

On the eastern coast, on the other hand, the country is comparatively

smooth and well cultivated, and a line of railroad extends on this side

all the way from Edinburgh to Inverness. Thus the party might, as

Grimkie explained the case to them, either go up to Inverness from

Edinburgh by railroad, on the eastern side, through a smooth and

beautiful country filled with green and fruitful fields,, and with

thriving villages and towns,—or by steamboat from Glasgow on the western

side, among dark mountains and frowning precipices, and wild but

beautiful solitudes. Florence voted at once and very eagerly in favor of

the mountains.

“Then there is a third course still that we can take," said Grimkie; “we

can go up through the center of the island."

“And how shall we travel in that case?” asked Mrs. Morelle.

"There is no railroad yet through the center," said Grimkie, “and no

steamboat route. So we should have to go by coach, or else by a hired

carriage."

“And what sort of a country is it?” asked Florence.

“Some parts of it are very beautiful" said Grimkie, “and some parts are

very wild. We should go through the estates of some of the grandest

noblemen in Great Britain. The guide book says that one duke that lives

there planted about twenty-five millions of trees on his grounds, but I

don’t believe it.”

“It may be so" said Mrs. Morelle.

“Twenty-five millions is a great many,” said Grimkie.

“I don’t see where he could get so many trees,” said John.

“Probably he raised them from seed in his own nurseries,” said Mrs.

Morelle.

“He could not have nurseries big enough to raise so many,” said John.

“Let us see,” said Grimkie. “Suppose he had a nursery a mile square and

the little trees grew in it a foot apart. We will call a mile five

thousand feet. It is really more than five thousand feet, but we will

call it that for easy reckoning. That would give us five thousand rows

and five thousand trees in a row—five thousand times five thousand.”

Grimkie took out his pencil and figured with it for a moment, on the

margin of a newspaper, and then said,

“It makes exactly twenty-five millions. So that if he had a nursery a

mile square, and planted the trees afoot apart, he would have just

enough.”

“Never mind the Duke of Athol's trees,” said Mrs. Morelle. “Let us

finish planning our journey.”

But here the door opened and two waiters came in bringing the dinner. So

the whole party took their seats at the table. Afterward, while they

were sitting at the table, Mrs. Morelle asked Grimkie what he had

concluded upon as the best way for them to take of all the three which

he had described, in case they should decide to go to the Orkney

Islands.

“You see, Auntie,” said he, “we shall of course go by railway from here

to Glasgow, and it will make a pleasant change to take the steamboat

there. It is a beautiful steamboat and excellently well managed. It is

used almost altogether for pleasure travelling, and every thing is as

nice in it as a pin. Then it must be very curious to see the green glens

and the sheep pastures, and the highland shepherds on the mountains, as

we are sailing along. Then when we got to Inverness we shall change

again into the stage-coach, to go to Wick, and at Wick we shall take the

deep sea steamer. So we shall have a series of pleasant changes all the

way.”

“I am not sure how pleasant the last one will be,” said Mrs. Morelle.

“If we have pleasant weather and a smooth sea, I think it will be very

pleasant indeed" said Grimkie. “It will be amusing to think how far we

are going away, and also to see what kind of people there will be going

to the Orkney and Shetland Islands.”

“But suppose it should not be pleasant weather and a smooth .sea.”

“Then we will not go,” said Grimkie. “We will stop at Wick and come back

again, if we do not wish to wait for the next steamer. It will be a very

curious and interesting journey to Wick, even if we do not go any

farther at all.”

Mrs. Morelle said that she would consider the subject, and give her

decision the next morning.

The next morning she told the children that she had concluded to go, and

to follow the plan which Grimkie had marked out for the journey.

“But there is one thing that we must not overlook,” said she. “We must

be sure that we have got money enough. So you must make a calculation

how long it will take us to go, and how much it will cost. Of course you

can not calculate exactly, but you can come near enough for our purpose.

When you have made the calculation, put down the items on paper and show

it to me.”

Grimkie made the calculation as his aunt had requested. He did not

attempt to estimate the expense of each day precisely. That would have

been impossible. He reckoned in general the hotel expenses, all the way,

at so much a day, from the number of days which it would require, and

then from the railway guide and other books he found what the fares

would be for the travelling part of the work. He also made a liberal

allowance for porterage, coach hire, and other such things. When he had

made out his account he gave it to Mrs. Morelle, and she' showed it to

the keeper of the hotel, and asked him if he thought that was a just

estimate. Mr. Lynn, after examining it carefully, said that he thought

it was a very good estimate indeed, and that the allowances were all

liberal; and as the total came entirely within the amount which Mrs.

Morelle had with her in sovereigns, she concluded that it would be safe

to proceed.

The party accordingly went to the station that very afternoon and took

passage for Carlisle, a town near the frontier of Scotland, and on the

way to Glasgow. |