|

MR. WILSON'S PASTORS.-AN

ADDRESS.-HIS MARRIAGE. - HIS HOME. - TEMPERANCE. - HARRISON CAMPAIGN.-

HIS COURSE IN THE GENERAL COURT.

BY the dismissal of Rev.

E. D. Moore from his pastoral office at Natick, and by his consequent

departure from that town, Mr. Wilson lost the daily counsel and

encouragement of a sincere and valuable friend, who sympathized with him

in his political views, and had confidence in his ultimate success. The

kindest social relations still subsist between these two gentlemen; and

it is doubtless gratifying in a high degree to Mr. Wilson's earliest

living pastor to see his expectations in regard to one of his society in

Natick so fully realized.

The Rev. Samuel Hunt, an

able minister and a steady advocate of human freedom, succeeded Mr. Mr.

Moore in July, 1839, and continued as Mr. Wilson's pastor until 1850. He

also felt a profound regard for the spiritual we1fire of his

distinguished parishioner, and aided him in his researches. He rejoiced

in the noble stand which his friend took against the aggressions of

proslaver power, and labored with the clergy and the churches of his

association to sustain him, He was well aware of Mr. Wilson's

intellectual energy and growth, of his integrity, of his sincere

devotion to the cause of freedom; and he predicted his political

success. He endeavored so to guide him as to make it sure.

Under the faithful ministry of Mr. Hunt, the

mind of Mr. Wilson became seriously impressed with the momentous

relations between himself and his Maker, so that he not only listened

with profound attention to the instructions of the sacred desk, but

sometimes took an active part in religious meetings. He taught for

several years a Bible-class in the sabbath school with great acceptance;

and the members of that class are now, for the most part, intelligent

and progressive members of the church.

On his part, Mr. Wilson encouraged and

supported Mr. Hunt in the arduous labors of his ministry: he sympathized

with him both in joy and sorrow; and the tie that early bound their

hearts together still remains unbroken. On the presentation of a watch

to Mr. Hunt at his retirement from his pastorate at Natick, Mr. Wilson

made the following beautiful and affectionate address: -

"RESPECTED FRIEND, - The relations which

have existed between us for eleven years having now been dissolved, we

have assembled here to-night to express our high appreciation of your

services as a pastor, our profound respect for your character as a man,

and our personal regard for you as a friend. We are here also to pass a

few fleeting moments in your society; to exchange with you a few parting

words; to take you once more by the hand; and, with hearts overflowing

with emotion, to bid you farewell.

Could these friends have controlled events,

the chain that bound us together in the relation of pastor and people

would have remained unbroken: you would have continued with us and of

us. Having passed your days with us in the performance of your duties,

participating in our joys and sharing in our sorrows, when your 'race of

existence was run,' we would have you repose in the bosom of our

mother-earth with the people of your early choice, - in yonder spot,

hallowed and consecrated as the last resting- place of this people and

their children.

"But it has been ordered otherwise. We must acquiesce in an event we

could not avert. You are to leave us to seek other fields of labor, to

form new relations, to gather around you other friends. But, sir,

wherever you may go, be assured that you will bear with you our warmest

wishes that Heaven will shower upon your pathway its choicest blessings.

Wherever in the providence of God you may be summoned to labor, may

friends - true-hearted, Steadfast friends - cluster around you to cheer

you onward in every beneficent effort to advance the cause of religion

and humanity! You

will leave behind you, sir, in retiring from the place you have so long

filled, many evidences of your deep and abiding interest in our present

prosperity and future welfare. The recollection of your many acts of

kindness will be cherished by us with unabated affection until the

hearts upon which these acts are engraved shall cease to beat forever.

Desirous that you should carry with you some

parting token of our friendship, your friends have purchased the watch I

hold in my hand, and have commissioned me to present it to you. In their

behalf I beg you to accept it. Take it, sir; cherish it, not for its

intrinsic worth (for it is of slight value), but as a trifling tribute

to your worth, and memento of the respect, esteem, and affection of its

donors. As a memorial of our friendship, I trust you will not consider

it altogether valueless. It will not beat more accurately the passing

moments than will the pulsations of our hearts ever beat responsive to

the friendship we entertain for you.

We fondly indulge the hope, sir, that in

after-life, amid its pressing cares and duties, it will sometimes remind

you of the friends of those

'Earlier days and calmer hours,

When heart with heart delights to blend.'

In the calm and quiet of your study, where

the world and its cares are shut out, as the ear shall hear it beat the

fleeting seconds, or the eye see it mark the passing hours, may it

recall to mind reminiscences of the past! - recollections of these

scenes; of this place, where were passed the first years of your

ministry; where were spent so many years of your early manhood, - that

portion of existence when impressions are most indelibly engraved upon

the mind and heart; where your children were born; and where your home

was blessed and made joyous by the grace, love, and piety of the wife of

your bosom, the pure and gentle being, the loved and lost one, who now

sleeps far away amid the scenes of her youth, but whose memory will over

be fondly cherished by this people; for

'None knew her but to love her,

Nor named her but to praise.'"

On the twenty-eighth day of October, 1840,

Mr. Wilson was united in marriage, by the Rev. Mr. Hunt, with Miss

Harriet Malvina Howe of Natick. She was the daughter of Mr. Amasa and

Mrs. Mary (Toombs) Howe, and was descended on her mother's side from Mr.

Daniel Toombs, an early settler of the town of Hopkinton. She was a lady

of good education, refined in sentiment, gentle in manner, and

remarkable for the sweetness of her disposition. By her unostentatious

way of' doing good, she made religion lovely. Her thoughts were noble;

and her influence upon the society in which she moved was like the

fragrance of flowers. She could not but make her home happy; and her

husband had a just appreciation of her excellence. For him, in his toils

and trials, her clear voice was an inspiration. In her he beheld a

pattern of true womanhood, and for her sake he longed to deserve well of

his country. To her sweet influence over him may be in part attributed

that delicate and profound respect which he entertains for woman, that

sincere regard which he manifests for her intellectual and social

elevation. His ideal of' womanly virtue and devotion was realized in her

pure and lovely life of trust and duty.

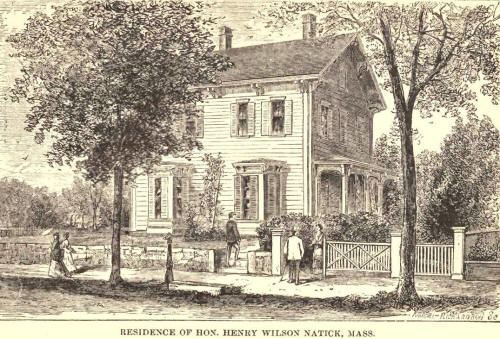

Three or four years subsequent to his

marriage, Mr. Wilson built on Central Street, in Natick, the neat and

commodious dwelling-house which he has since occupied. It is furnished

with republican simplicity, yet with elegance and taste. To its

hospitalities his friends and neighbors always find a cordial welcome;

and the absence of luxury and parade is more than compensated by smiles

of cheerfulness, and words of good will. On the eleventh day of'

November, 1846, the hearts of the parents were gladdened by the birth of

a son, whom they named Henry Hamilton. He was their only child.

In principle and in practice, Mr. Wilson has

always been opposed to the use of intoxicating liquors as a beverage;

and to his strictly temperate habits may in part be ascribed that robust

health and physical strength which he now so eminently possesses. As

early as 1831 he joined a temperance society in Farmington; and in

public and in private he has ever exerted his influence to dissuade his

fellow-men from the use of stimulating drink.

In a speech in Tremont Temple, Boston,

April, 1867, he said, -

"I shall strive ever and always to promote

and advance that great cause of our common humanity. It is no merit in

me that has made rue a life-long friend of temperance. God in his

providence gave me no taste, no desire, for intoxicating liquors; and

every day of my life, as I grow older and see the measureless evils of

drunkenness, I thank my God that he gave me no desire for that which

degrades and levels down our common humanity.

"From my cradle to this hour I have seen,

felt, realized the curse of intemperance. When my eyes first saw the

light, when I came to recognize any thing, I saw and felt some of the

evils of intemperance; and all my life long to this hour, and now, my

heart has been burdened with anxieties for those of my kith and kin that

I loved dearly. With no desire for the intoxicating cup, with the evils

of intemperance about and around me, and with a life burdened with

anxieties for dear and loved ones, it is no wonder, ladies and

gentlemen, that I have abhorred drunkenness, while I have loved and

pitied its victims."

Aware of his regard for temperance, and

having confidence in his ability as a thinker, his friends in Natick,

advocating what was known as the "Fifteen-gallon Law," presented his

name in 1839 as a candidate for the General Court. He failed by a very

few votes of an election, and continued quietly manufacturing shoes, and

studying the condition of his country. No representative was sent that

year from Natick; and the party in opposition to that law placed Marcus

Morton in the executive chair of the State.

In 1840 occurred the celebrated presidential

campaign, in which William Henry Harrison, ''the hero of the Thames and

the Tippecanoe," was brought forward by the Wings in opposition to Mr.

Van Buren, then president. The experiments of the government upon the

currency had embarrassed the financial operations of the country, and

had seriously affected the industrial interests of the North, and

reduced the wages of the working-people. Hard times came on. The

laboring-classes murmured against the measures of the government, and

keenly criticised the course of the president and his cabinet. Mr.

Wilson, ever on the side of the working-men, felt the pressure, and saw

the ruinous tendency of Mr. Van Buren's financial policy and, although

he had hitherto sympathized with the Democratic party, now came

prominently forward with the Whigs, and espoused the cause of Mr.

Harrison. "Having entered life on the working-man's side," says the

author of "Men of our Times," "and having known by by his experience the

working -man's trials, temptations, and hard struggles, he felt the

sacredness of a poor man's labor, and entered public life with a heart

to take the part of the toiling and the oppressed."

Up to that period, no political campaign in

this country had so aroused the enthusiasm of the people. Mass-meetings

were held in churches, halls, and groves; log-cabins were erected, and

sometimes mounted on wheels, and drawn from town to town; banners with

mottoes were unfolded, and immense processions of all ranks and classes

bearing torchlights were formed. The ablest speakers took the stand; and

eloquence and patriotic songs set forth the virtues and exploits of "the

hero of North Bend" before the people.

"Tippecanoe and Tyler too" rang as a war-cry

through the Union. Mr. Wilson shared in the enthusiasm. He studied well

the course of legislation as presented in "The Washington Globe," and

made his first campaign-speech in the Methodist meeting-house at Natick

in opposition to Mr. Amasa Walker, who was an advocate of a specie

currency and of the general policy of the national administration. The

ability of Mr. Wilson as a public speaker was at once acknowledged. He

was invited to discuss the questions of the day in many other places;

and, during the campaign, made more than sixty speeches in the

neighboring towns and cities. In Charlestown, Cambridge, Roxbury,

Lowell, Lynn, Taunton, and other towns and cities, he addressed large

and enthusiastic audiences with telling effect; so that the general

exclamation was, "How came this Natick shoemaker to know so much more

than we do on national questions?"

The answer might have been, "This Natick

shoemaker was studying 'The Federalist' and the proceedings of Congress

while you were asleep.

In some instances, attempts were made to

interrupt him in his speaking; but holding himself steadily to the point

in question, and to his good nature, of which the fund seemed

inexhaustible, he manfully maintained his ground, and carried his

audiences with him. He spoke extemporaneously, but never without careful

preparation. He read the best models of American eloquence, - such as

Adams, Everett, Otis, Channing, Webster; and, after committing parts of

his speeches to memory, he would sometimes retire to Deacon Coolidge's

old oak-grove, and there rehearse them to himself alone. He is

remembered by those who heard him in this campaign as a young mail lithe

and agile form, of an intellectual cast of countenance, clear

complexion, earnest, searching voice, and sparkling eyes. He usually

bent over the desk in speaking, as if to come as closely in contact with

his audience as he could. His object seemed to be to reveal the thought

of his hearer to himself; and herein lies one secret of a speaker's

power. He also defended his positions by a very frequent appeal to

facts; and one who well remembers him at that time avers, "He had a very

winning way in presenting them."

At the close of the campaign, he had the

pleasure of seeing Mr. Harrison, for whom he had spoken so many times,

elected to the presidential chair by a large majority, two hundred and

thirty-four to Mr. Van Buren's sixty electoral votes, - while he himself

was chosen a representative from the town of Natick to the General Court

of Massachusetts. The legislative hall is now his academy; the

constitution is his text-book, and liberty his teacher.

When he entered the House of

Representatives, he observed that an honest farmer, twenty years his

senior, had drawn one of the most eligible seats in the hall; and he at

once offered him three dollars for an exchange. The farmer gladly took

the money; for one seat to him who never spoke was just as good as

another. But, some time afterwards, he referred to the circumstance as

revealing the pride of the young member. "No," said one who better knew

his spirit: it reveals his foresight. He gave you three dollars for your

seat in order that he might be in the best position to hear the

arguments of other members, and also to present his own with most

effect. This style of doing things, if carried on, will give him

influence here." It was carried on. He entered upon his legislative

career with the determination of bestowing his whole time and attention

upon the business coming before him. With sleepless vigilance he watched

every transaction, listened to every speaker, and followed every

question. He was a working-man; he entered the legislative hall to work;

he did not fail to work; and workers win.

It is noticeable that his first legislative

speech was in favor of the working-man. It was delivered Jan. 25, 1841,

on a bill to exempt laborers' wages from attachment in certain cases. He

said the honest poor of the State would deprecate the passage of such a

law: it would protect dishonesty. The class of men who lived upon the

earnings of others were daily increasing. There were many men, too, who

judged of morality by law alone. Such a law would impair the credit of

the poor man. He hoped this bill would be considered on its merits

alone, with no intermixture of party-spirit, he sympathized with the

poor men with whom he had been reared, and with whom he now was. He

moved to strike out the enacting clause.

Inured as he had been to hard and

unremitting labor, and with sympathies alive to human suffering, it was

natural that Mr. Wilson should be opposed to the whole system of

domestic servitude. His mind revolted at the wrongs the bondman bore in

a boasted land of liberty: he keenly felt the cruelty of that code of

laws that held him subject, and without redress, to the caprice of an

insolent and hard-hearted master. The instincts of a noble nature, the

teachings of the gospel, the training he himself had undergone, the

philanthropic spirit of the age, the opinions of the founders of the

Constitution, all conspired to lead him to abominate the traffic in

human blood, and the tyranny of subjecting innocent men and women to

servile labor. The more he thought upon it, the more iniquitous appeared

the system: it despoiled the slave of his just rights; it demoralized

the master; it impoverished his country. At the same time, he saw that

the slave-power, ever intolerant and exacting, had long held ascendency

in Congress; had by the craftiest plans extended its territory so as to

maintain that ascendency; and, while menacing the North, had

contaminated the source of political power, and brought the free States,

to a great extent, into subserviency to its schemes of aggression.

Such, it is believed, were Mr. Wilson's

views and sentiments at this period; and, if he did not enter the

abolition ranks, it was not because he was opposed to their leading

principles, but because he hoped to exert a stronger influence towards

the ultimate redemption of the slave by acting with the progressive men

in the Whig part. In the legislature his voice was ever heard, his vote

was ever cast, on behalf of the rights of those in bondage. In the House

of Representatives, in 1841, he advocated the repeal of the law, which

has been termed the last of the slave code in this State, forbidding the

intermarriage of blacks and whites; and, in the next session, made

another strong speech in opposition to the law, maintaining that it was

founded on inequality and caste. He declared "that the bill was not

inspired by political, but by humane motives and, though it might be

defeated then, it would ultimately be enacted. It was only a question of

time." This obnoxious law was repealed at the next session of the

legislature. In November, 1842, Mr. Wilson was a candidate for the State

Senate; but the Whig party was that year defeated in his county, as it

was in the State. There being no election of governor by the people, the

legislature, in January, 1848, elected Marcus Morton for a second term.

In 1844 Mr. Wilson obtained a senatorial seat, and took all part in the

deliberations of that body, ever ranging himself upon the side of'

progress and reform. He made an elaborate report on military affairs,

and carried it through the Senate.

He was again a member of the same body in

1845, where he again labored successfully for the improvement of the

military system of the State, and also to improve the condition of the

colored people. He strenuously advocated the right of negroes to seats

in the railroad-car, from which they had in several cases been

insolently ejected; and also their right to admission to our public

schools, from which prejudice had excluded them.

A bill reported to the Senate, providing

that any child unlawfully excluded from the public schools should be

entitled to recover damages, had been rejected. Moving the next day a

reconsideration of this vote, Mr. Wilson made all speech in behalf of

the bill, in which he said that he considered it the most important one

which had come up that session.. "It concerned," said he, "the rights

and feelings of a large but humble portion of our people, whose

interests should be watched over and cared for by the legislature; whose

imperative duty it was, when complaints were made of the invasion or the

rights of the poorest and the humblest, to provide a remedy that should

be full and ample to secure and guard all his rights." He said the

common-school system, the pride and glory of Massachusetts, was based

upon the principle of perfect equality, and that the distinction set up

at Nantucket aimed a blow at its very existence. The colored people

said, and rightly, that their feelings were trifled with, and their

rights disregarded. Denouncing the spirit that excluded colored children

from the full and equal benefits of common schools, he said, "It is the

same which has drenched the world with blood for six thousand years,

made a slave- holder in South Carolina, and a slave-pirate on the coast

of Africa." He said that those whose rights he wished to guard and

secure had but little influence or power; while those who opposed them

had both, and were only too willing to use them for their own

aggrandizement. It was more popular to keep along with the current of

prejudice, than, by resisting it, to be denounced as a "radical or

abolitionist." "In retiring from the legislature," he said, "I am

sustained by the consciousness that I have never uttered a word or given

a vote against the rights of any human being. I had far rather have the

warm and generous thanks of one poor orphan-boy down on the Island of

Nantucket, that I may never see, nor even know, than to have the

approbation of every man in the Commonwealth, whether in this chamber or

out of it, who would deny to any child the full and equal benefits of

our public schools."

Such sentiments are creditable to the

senator's heart. They had their effect on the Senate. Mr. Wilson's

motion was adopted by a large majority: the bill was committed to the

judiciary committee, which reported a similar bill that became the law

of the State. Thus slowly, through the influence of the friends of

freedom, Massachusetts came to see and to acknowledge the rights of a

long abused and shamefully-neglected race of people. Between the lofty

and the lowly there was need of a mediator, who by his intellect could

reach the one, and by his band of toil the other; and such was Henry

Wilson. "Then on!

for this we live, -

To smite the oppressor with the words of power;

To bid the tyrant give

Back to his brother Heaven's allotted hour." |