To pass from the

Highlands to the Borders is of the nature of an anti-climax. Nothing

here was lofty enough to give shelter to such snow plants as may

have retreated up their sides. The southern uplands are moorland and

sub-alpine.

What rare wild

flowers there are, may best be shaded off by what are missing. No

rare saxifrages, no snowy gentian, no rock speedwell, no mountain

forget-me-not, of the northern alpine area, grows on those more

moderate heights with their shallower glens.

I am settled by the

Border stream, and looking forward to a long walk over the hills.

This is in the yearly round. It has been my delight to make myself

as much at home on the heights above the Tweed as on those of the

Perthshire Tay and the Forfar Isla and Esks.

Several days are

spent in getting myself into condition. In my day and night fishing

I have done a good deal of tumbling up and down the banks; but

climbing is a thing apart, and needs a training by itself.

I start up one of the

wild side-glens of this portion of the valley. The burn,

innocent-looking as it is to-day, responds like an untamed colt to

the lightest lash of a cloud, by breaking into a gallop, or clean

taking the bit between its teeth and careering headlong down.

Oppressively desolate

and lonely at first, these glens take possession of one after a

while, and become wonderfully attractive. A day with the rod is

pleasant, if only as a strong contrast to casting along the milder

course of the Tweed. One gets used to the crossing and recrossing of

the sheep over the stony channel. So, too, do the trout. The

paddling of the “trotters” does not seem to scare or keep them from

taking the hook.

Countless little

springs, without the strength to form a channel or a current to lend

them character, sipe through the grass on to the road, to find some

hidden way into the stream. Their moist track down the slope is

marked by the purple of hairy sedum, by the pink of alpine willow

herb, and the yellow of the marsh buttercup.

The goal is

Windlestrae Law—the highest hill in the neighbourhood. The peak—more

than two thousand feet above—is, as yet, hidden from sight by

intervening ridges. A slope, not very steep in itself, is so beset

with shrubs as to put one’s endurance to the test. There is no

escaping a wide belt of heather. Ling, in this case, certainly

deserves its name, being longer than usual.

Heather, when

knee-deep, so that one cannot very conveniently lift each step clear

over the top, is very troublesome to walk among. From its recumbent

habit, it has a nasty tendency to catch one just above the boot.

Three feet of ling,

two of which are trailing, is not only a drag, but very much of a

trap as well.

In case of undue

haste, one is apt to be tripped up and rolled over and over among

the pink blossom. The latter experience mainly overtakes one in

running down-hill. Climbing is too serious a business in itself for

any such frivolity.

The moist places are

thickly dotted with sphagnum, both stout and fragile; and of all

pleasant shades, from very pale to ruby-tipped. The fleecy water

variety floats out on the little dark pools of the peat. Much of

it—more, I think, than ever I saw before—is in fruit. In my mental

register, that experience is noted down as “A day among the

sphagnums.” In my little map, which no one ever sees, Windlestrae is

named Sphagnum Hill.

A day among the

cloudberries, too. These smallest of our native brambles seem

well-nigh to cover the summit. Many bear fruit. Some are in flower—a

very pretty white blossom, like the rest of the brambles. One entire

cloudberry, root and all, I put into my buttonhole, and wear for the

rest of the day.

The boggy

ground—rather too boggy, in some places, for comfort—seems to suit

the plant. It is pretty widely distributed under similar conditions,

and is perhaps more characteristic of these uplands than any other

form. It is as near an approach to an alpine as we are likely to

find. Since there can be no rivalry between a moss and a wild

flower, Windiestrae also appears on my map as “Cloudberry Hill.”

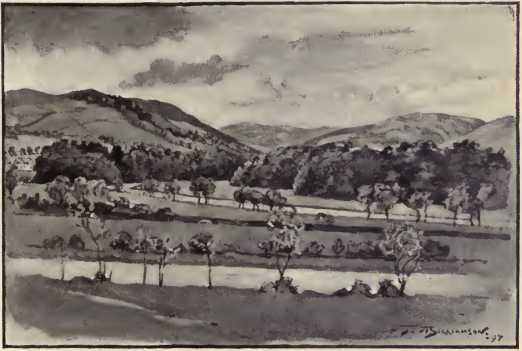

A very early hour of

the second morning after finds me dropping behind a curtaining

ridge, out of sight of the placid Tweed. Before me, a pastoral

region slopes down to form the banks of the stream, and melts away

over the gently rounded hilltops. .

The vale is

suggestive of undefined emotions and pensive thoughts. Appealing to

the imaginative and impressionable of bygone days, it has found

utterance in sad and tragic ballads. Who says that a scene may not

have a character? Is it fancy that there are lines of ineffaceable

sorrow? I sit down by Yarrow-side to rest. The way left behind,

though not long,—only ten miles,—needed a good deal of stiff

climbing.

The whole morning had

been delightful. As yet there is no hint of change to quicken the

pace :—only a little mist on the distant hills ahead, whence the

gentle airs come. A leisurely saunter along the even ground will be

a pleasant contrast to the ups and downs.

The lake is a part,

the eye of the scene. . As in the case of other eyes, much of the

expression is there —reflection among the rest. Its shadows are

reflections, in the deeper sense. Sad St. Mary’s! A good deal is in

that “sad.” In its silent depths, memories lie. When I come in

sight, it is in one of its quieter moods, not cheerful; it never

is—only still.

Even as I look, the

aspect changes: the trouble comes to the surface, the face darkens,

the spirit of gloom sweeps over it with a moan. Out of the dark

cloud comes the rain. Storm on St. Mary’s has something of a human

outburst in it. Rain falls with the bitter significance of tears.

Five minutes are long

enough to wet one through. The seven miles to “Tibbie’s” become a

dogged walk with water—water everywhere, from cap and finger-tips to

boots. The Selkirk coach has just come in, full of' passengers.

There is no getting near the fire, and the floor looks miserable

with the drippings.

A lull tempts me out

again. Along the shores of “the Lake of Lowes” the mist-winged storm

comes along worse than ever. Now all is natural. The sadness has

dropped behind—only, the wildness is in the mountain fastness, from

which the wind and the mist come forth, to play roughly on the

plain.

The ascending road

leads into the midst of the fray—into the very presence of the

raider. The storm takes visible form in the mist which sweeps

past—swirls, lifts for a moment to reveal a few yards of the

hillside, and then, for a like brief interval, settles round,

wrapping me to my very clothes.

Two hours later, when

I am beginning to think that I have been the plaything of the

elements about long enough, I come suddenly on shelter. I do not see

the cottage until I can almost touch it. In some of the stiller

moments of the storm I must have passed unawares; but the veil

lifts, and there it is.

The thought of

lodging had not troubled me when I started, nor in the earlier hours

of the day. If it came, good and well; if not, then the earth was

big enough. But I had not reckoned on this. Certain who preceded me,

tell of their experience in the same neighbourhood :—,

“As there were large

quantities of the common bracken, we unanimously resolved to bivouac

there for the night; and having partaken of our evening meal, and

drunk from the clear gushing stream, we laid ourselves down to

sleep, with the sky above as our curtain, and the majestic hill at

our backs and on either side as our bed-posts. Our love for the

romantic seemed now to be indulged to the full; and what strange

thoughts came into our heads as we peeped out through the ferns

which grew so thickly around us!

“One by one we

dropped to sleep; but scarce had we shut our eyes, when our hands,

which we had left outside the covering as barometers, told us of a

change of weather. We should soon have been drenched had we not

taken up our beds and adjourned to a hut, which, to all appearance,

served as a maternity hospital for all the sheep in the

neighbourhood.

“It was now twelve

o’clock, with the rain pouring in torrents, and the wind whistling

in fitful gusts through our fragile domicile, and one of our

sorrowing friends was heard to whisper—

"Sic a niglit As

ne’er puir sinner was abroad in.”

Sic another night was

this, and such mayhap would have been my fate had the storm delayed

its coming. In my weakness, the prospect of a tighter roof brings a

sense of relief. I had been here before.

A shepherd’s cottage

has been converted into a sort of hostelry, for the behoof of

passers through the defile. In old days it might have been called a

“Spital.” The house is full; there is not much to fill. I might not

have been lodged at all, but that it was a night

Wherein the cub-drawn

bear would couch,

The lion and the belly-pinched wolf

Keep their fur dry.

Even the four dogs are inside.

The shepherd’s wife

not only takes me in, but clothes me. The suit is her husband’s. I

never saw the wearer, who was away at Peebles Fair with the season’s

lambs; but I have good reason to suppose that he is twice my weight.

For two whole days I

live and move and have my being in these clothes. I revel in them,

tent in them, roll about in them, insist that my own are not dry,

until the kindly lender laughingly asks if I would like to take them

away with me.

Anglers gather in

from the streams, or are blown in by the gusts which set every door

a-rattling and every inmate a-shivering. No one has been successful.

Rising water seldom yields a basket. Trout are too much concerned in

looking after themselves, and in seeking the eddies which are last

to be blotted out.

These men have been

tempted up from Moffat by the rain-bearing clouds, which blew from

that direction, and had got more than they wanted. The coach rattles

up and takes them off. The house is left to those who are to stay

there.

“I would just hae to

be doin’ wi’ a seat at the kitchen fire, as the room was let to a

lady and gentleman frae Liverpool.”

That is how my

hostess puts it. Worse fate by far might have befallen me.

Happily, the

gentleman overhears, and courteously invites me to join them. The

blind is drawn, the lamp lit, and chairs placed round the table. In

a rubber of whist we forget the storm, or only hear it at intervals,

to the increase of our sense of comfort by contrast. The louder it

raves, the more we hug ourselves. Had you ever a rubber of whist

under similar conditions ? If so, you. will know all it means.

I am abroad, bright

and early. Never fresher morning broke over these or any other

hills. The son, a shepherd like his father, is called in, and gives

minute directions how to go so as to avoid the peat-hags. I am sure

I understand him, and so take my way up the slope. The sundew grows

in moist places; so does the water forget-me-not, the rarest of its

kind to be found on these hills.

Of course I do not

avoid the peat-hags. Indeed I get into the very midst of them; and

having once lost a track, at best so faintly indicated that only a

shepherd could follow, I never recover it. More than once I have to

descend my own height on to a treacherous-looking black bottom,

rendered none the firmer by yesterday’s rain. By sheer persistenceI

somehow bore my way to Loch Skene.

The mountain sorrel

is everywhere. The small crowded flowers, rising above the

kidney-shaped leaves, are effective, from the reddish tint they

share with the rest of the family. Natural beauty owes much to lowly

agents. The wilds could better spare many a brighter flower. This is

a sub-alpine that passes into the lower alpine regions, and after

that reappears, to give a welcome touch of colour to the arctic

lowlands. It is thus interesting, as being one of the northernly

tending arctic alpines.

The mossy saxifrage,

so familiar in our gardens for its cushions of much-cut leaves, is

the commonest of the few — three, I think — sub-alpine species

growing on these hills. The other two are the starry and

opposite-leaved saxifrages.

Still another plant —

the alpine enchanter’s nightshade—is characteristic. The ordinary

species covers the floor of some of the woods lower down. Neither is

to be regarded as strictly lowland ; and the alpine form may only be

the other, modified by changed conditions. Both have in their

fantastic flowers a certain weird suggestiveness of their name,

especially when growing in the shade.

Somewhere around, a

friend, who had his home by the Tweed-side, once made an experiment.

He was a rare man, such as one meets among the common herd only

twice or thrice in a lifetime. Dearly he loved these, alpine fairy

plants; and he had a strong wish to get others to care for them as

well, and to take a pleasure in climbing the hills to look at them.

Out of very

unpromising elements he formed an Alpine Club, which exists to this

day, although its pure and noble guide is gone. There are those who

reserve such words as unpractical for such schemes as these; but

this one, happily, for those who became a part of it, took shape.

Some who ran the ordinary risks of becoming sordid, feel all the

better for a day on the hills which overlook their homes and dwarf

their everyday lives.

My friend, naturally,

wished to see his favourites as often as possible. But it was a long

way to come ; and, living so far apart as they did, he could visit

only two or three at a time. He was, for all the world, like a man

whose children are scattered, and who grieves that he can no longer

have them all together as he used to do. So he fixed upon a common

home, and spent a few summer days in tenderly gathering two or three

of each, and placing them as near together as their differing habits

would allow.

One can picture the

scene. 1 think, by patient search, could pick it out. And it would

be worth finding; for if ever spot on earth was hallowed by the

purity and simplicity of man, that spot was.

It would be bordered

by a channel, whose rocky shelving, laid bare by the rude torrent,

gave root-hold to the starry saxifrage. It would include a marshy

area, tender with the blue of forget-me-not, white with mountain

avens, and touched with the red of sundew. It would possess a

shadow, quaintly pretty with the spikes of enchanter’s nightshade;

and a rough track lit with the scarlet fruit of the stone bramble,

and overrun with the white purple - tipped blossoms of the wood

vetch. These at least.

Alas ! for the best

laid schemes. His face wore a half-vexed, half-amused look as he

told me the sequel. One day he reached his paradise, to find it

despoiled; and, some time afterward, he learned the cause. Certain

botanists from Edinburgh, with vascula of greedy dimensions, came by

chance that way, and doubtless reported the spot as an extremely

rich floral area.

Loch Skene is flanked

on one side by Whitcoom, which shows its summit just over the

sub-alpine region — some two thousand six hundred feet above

sea-level. This mountain is interesting as forming the culminating

height in these parts; moreover, it stands at the touching point of

Selkirk, Peebles, and Dumfries.

In these uplands,

Whitcoom holds a position similar to that of those other culminating

heights which at once attach and separate Aberdeen, Perth, and

Forfar. It is the hilly centre and stronghold in the south, as they

are in the north.

What is not found

here need scarcely be looked for elsewhere. And yet the chief

rarities its slopes have to offer are the alpine meadow rue, the

cranberry, and the veined willow.

If they fell within

the popular notion of wild flowers, it would delight me to talk

about the ferns; the rather as I regard these hills as the fern

garden of Scotland, just as I regard the northern hills as the

alpine garden. If some of the rarer forms are absent, those which

are there, abound.

The brittle fern, the

most graceful of all the forms—and what is rarity, compared with

grace, except to the dry - as - dust naturalist — is, in many

places, as common as the bracken or the grass.

The male parsley fern

waves above the wastes of stones, and hides away the rudeness under

its feathery fronds : the oblong Woodsia is common here—a corrie or

linn, in the flank of this same Whitcoom, is a favourite haunt;

while the filmy fern, in countless numbers, seems to filter every

drip of water.

Before leaving the

hostelry, I open the visitors’ book and run down row upon row of

uninteresting names. On turning over a page, my eye is arrested by

the sketch of a tourist’s back, with fishing - basket and other

belongings of sport and travel strapped thereon as if for final

departure. The man who did this knew the use of his pencil.

The lines beneath,

which I quote, less because of their literary merit—the author was

not so much at home with the pen—than for the pathos and human

interest behind a rude form, ran thus—

Scottish lakes are

bonnie,

Scottish hills are high,

So are Scots hotel bills—

Scotland, good-bye!