THE garden is a natural nursery; and the older it is, the larger its

share in the wild flowers of the surrounding country-side is likely

to be. Only by canopying the whole over and setting guards at the

gate could escapes be prevented, and the line between native and

cultivated kept sharp and distinct.

Seeds

rise on the lightest breeze, and may be borne miles away before they

come to rest. And if by field-side, or the margin of the wood they find

conditions to suit them, they will spring. At the autumn thinning,

clumps are thrown over the wall, which take root on the other side and

spread away outward, surely if slowly.

Sometimes an aesthetic member of a family will plant a cutting of some

favourite flower in one of her woodland or stream-side haunts. And, long

after, the touch of a vanished hand is seen there by some curious

passer-by.

It is

not many years since gentle hands scattered English wildlings over a

Scots park, and planted garden flowers in a Scots woodland. And there

they are now to witness if I lie. I could take anyone to the scene and

point them out. By the somewhat sad fortune which banishes daughters

from their homes when a property changes hands, the planters are no

longer there to watch their coming and going, as they did for many

seasons.

And

there they are likely to remain. I thought at the time that greater care

might have been taken in the choosing: that double flowers and those of

strange hues might have been left out.

But

nature will be sure to put that right by and by. The plants will revert

to the simpler state : will yield up all their petals save one outer

rim; will agree on some single hue, probably that they wore before their

captivity: and so recover their lost likeness to their wild brethren.

And, in years to come, delighted wanderers over the grass, or within the

shades, will wonder why this corner is so much richer than the rest of

the scene of which it forms a part. •

Frequently I come upon a curious patch of confusion, where a few

cultivated plants are struggling and fairly well holding their own, amid

a promiscuous crowd of such pushing plebeians as groundsel, chickweed,

and purple dead nettle. A ridge, not more than a foot high, enclosing a

space, is all that tells of the site of some peasant’s cottage, pulled

down, not too soon, probably, for the wellbeing of its inmates.

In

one of my walks I saw a daffodil growing on the banks of a rill. The

leaves were long and green, the flowers large, yellow, and single. The

whole plant was so healthy and happy-looking that I thought I had never

seen a daffodil before. Plainly it was better satisfied with its fresh

surrounding, than if it had been in some dry and dusty enclosure. No

wonder, seeing that it is naturally a lover of such moist places.

The

scene was shut in from the world on every side by a tree-crested ridge.

Few came by in a day. The nearest cottage was a long field’s-breadth

away. I looked for some trace of recent planting. The turf was firm, as

though long undisturbed.

For

miles around there was no wild daffodil besides. I question if the

county, had it been searched from end to end,—I had been over most of

it,—would have yielded such another clump. In some strange way, the

flower had got there. The scene suggested an aesthetic origin.

Only

yesterday I plucked a crimson sprig from a wild American currant, to

lighten up a little natural bouquet of brown wood moss and green

hawthorn leaf. The bush was growing vigorously and flowering freely in

the middle of a wood, a mile and a half from any town.

How

far this element goes to swell the sum of our wild flowers it were

extremely difficult to say. But it seems fairly certain that, were all

the escapes from gardens deducted, a less bulky volume would contain the

natives.

To

those who have watched the process—who have all but seen the flight of

the seeds over the garden wall; who have certainly been at the birth of

the strange seedlings, under the shadow of the wood, or on the moist

stream-side bank ; who have traced, season by season, the creeping of

the garden parings away from the wall—the possible additions from this

source will seem scarcely capable of exaggeration. And, on each

discovery, they will turn over the pages of their handbook with fresh

interest and curiosity.

I

have seen many such escapes, both swiftwinged and slow-footed, that are

likely to make good their hold and increase their distance from the

source, until the connection is broken. I could run over many more that

happened not so long ago. These are now as well able to look after

themselves as their neighbours, and are securely sandwiched »in print,

between two of the oldest inhabitants.

The

pace would be quickened, and many another surprise greet one by the way,

but that a garden flower in the wilds is no sooner detected than

uprooted, and transferred within some other enclosure. I have often

marked the showy fugitive, and next time I came by have missed it. A

check on the too rapid increase of quickly-spreading species is not

altogether a disadvantage, and a second check on the less ready

admission of aliens might be a further benefit. It seems a pity to

confuse, so as almost to lose sight of, our native lowland flora.

But

for this acquisitiveness there is no reason why “ none - so - pretty,”

which is at once the commonest garden plant, and one of the three

British alpines absent from Scotland, should not be familiar at the

roadside. Almost invariably it marks the site of abandoned cottages, and

blooms round the outside of old garden walls; and so far from being

discontented, it seems rather glad to get back to a wild state again.

I

find the neighbourhood of ancient fortresses often rich in their wild

flowers.

Within the enclosure of Craigmillar Castle grows the French sorrel.

Thence it seems to have spread into the south of Scotland and the north

of England.

The

date of its coming was the sixteenth century. The vanished hand, in this

case, that of Mary Queen of Scots. Amid her amiable weaknesses, Mary

seems to have included a liking for plants, and may almost be traced

from place to place by the relics she has left behind. Archangelica

appeared in 1568, a year or two after the return from France, and may

with some probability also be credited to Mary.

A

Forfarshire den which I am in the habit of visiting, is noted among dens

for its depth of shade, and the wealth of the flowering and flowerless

plants. There true wildlings grow along with many a suspicious native.

Everyone knows that Solomon’s seal is much more difficult to get rid of

than to plant. On being carried or thrown out of the garden, it will run

its stolons under the outside soil in quite a get-rid-of-me-if-you-can

sort of way. At one time it must have been placed there with a view of

enriching the flora of the den.

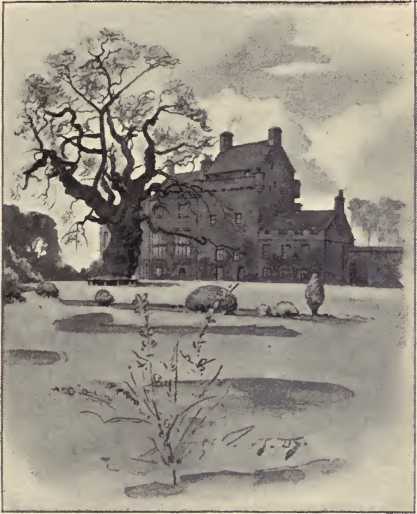

Now

it chances that on the top of the rock, a hundred feet or more above,

there stands a castle of more than ordinary interest, as contesting with

another the honour of being “ The bonnie house o’ Airlie.” The vanished

hand may have stretched from there. We cannot now deny the plant a place

among our Scottish wild flowers, without including many another of the

same den in our

Index Ex-purgatorius.

A

defile of much more modest dimensions seems even richer than this,

inasmuch as the many rarities are gathered into a narrower space. It has

been called a paradise of flowers. I always suspect these paradises,

where the wildlings I had searched for, separately, over many miles, are

all huddled within a few yards, and mingled with other flowers not

growing elsewhere outside an enclosure. I find myself asking for a

reason.

Early

in the year the rocks dipping steeply down to the cool water are covered

over with the great heart-shaped leaves, and brightened with the big

yellow flowers of Leopard’s bane. A faint sweet smell woos me aside to

the violets growing among the grasses of a bank. Though acquainted with

every yard of the country, I know no other bank on which the sweet

violet nods. Why should it be here ?

Not

fifty yards away, on the very edge of the rocks o’ertopping the

Leopard’s bane, is another castle of sixteenth-century date, once in

possession of the Grahams, kinsmen of “Bonnie Dundee.” Not much more

than a stone’s - throw away, a quaint building marks the site of

Claver-house itself.

It

may be that there were hands gentle enough for the work even in that

rude fortress, and that these things may have been planted much about

the same time that Mary was enriching the garden of Craigmillar Castle.

At all events, this place was inhabited, and either the gentle or the

simple must have placed them there. It

may be that there were hands gentle enough for the work even in that

rude fortress, and that these things may have been planted much about

the same time that Mary was enriching the garden of Craigmillar Castle.

At all events, this place was inhabited, and either the gentle or the

simple must have placed them there.

If

one looks for rare things in the neighbourhood of castles, the rude

engagements of whose inhabitants left them neither time nor taste for

trifles, and whose women had often to unsex themselves; much more

confidently may he turn to the peaceful surroundings of monasteries, and

the placid lives of monks. So much is said against these persons, who,

if the truth were kown, were probably neither better nor worse than

modern divines, that it is pleasant to record something in their favour.

And naturalists have reason to be grateful to them for more than one

service.

On

the north bank of the Tay, not far from the bridge, there are certain

banks and woods widely known for the luxuriance of their flowers. The

primroses are taller and more sweetly pale and scented than elsewhere,

and, contrary to their habit, grow so close together, as to preserve

through April and May an almost unbroken sheet of colour. The atmosphere

is delightful.

Hither the Dundee maidens appear, to gather, not one by one, but in

handfuls; and, furnished all too soon with what they come for, linger

about until the evening, and return with baskets which freshen the

streets and the jaded passers-by. p Above the pale and lowly primroses

rise, upon their stalks, the darker-coloured cowslips. Now, the cowslip

is not nearly so common in Scotland as in England; partly, perhaps, for

the want of dry permanent pasture.

Such

cowslips, as we have, frequently find niches for themselves in the

curious corners of woods. Nor do the Scots cowslips look quite the same

as those found growing on the English meadows. The smaller paler flowers

of the latter give it a more truly wild look. Here the whole plant is

larger, and more like the garden variety. This may be partly accounted

for by its woodland haunts, where the struggle for existence is not so

keen as in the meadow; or, when growing in the open, may point to a more

suspicious origin.

It

might be too much to say that the cowslip is not native to Scotland.

But, wherever it grows in such abundance, in company with a profusion of

common flowers of the sweeter kinds, the hand of man has probably had

something to do with it. And the only hands, vanished all of them, that

could have so enriched these Balmerino banks, and so added to the charm

of the scene and the happiness of the lives to come after, belonged to

the monks of the adjacent monastery.

Where

primroses and cowslips have grown so long together in sweet fellowship,

one may pretty confidently start on the pleasant hunt for oxlips. If

Oberon knows a bank whereon the oxlip grows, depend upon it, the cowslip

is in the meadow, and the primrose in the wood hard by. This form is

easily picked out, even at a distance, by the larger flower of the

primrose on the common stalk of the cowslip.

Hybrids between closely-related species, in plants as well as animals,

are doubtless commoner than we are aware of. All that is needful, in

many cases, is that the parent forms mingle freely on the same scene.

But this is not always so easy to detect, nor does it occur in the same

marked degree. Violets, albeit approaching as closely as primrose and

cowslip do, on the common margin of wood and meadow, modestly veil their

attachment. If oxlips are not more frequently observed in Scotland, it

is simply for the lack of cowslips.

A

rarer and more undoubted legacy of these Balmerino monks is “the lily of

the valley.” Unhappily, it is an example also of the tendency of

attractive plants, when they are sweet-scented as well, to disappear

behind the garden wall. There is reason to believe that its tenure of

Balmerino is already a thing of the past. The same fate must have

attended it elsewhere. Like

“

none-so-pretty,” it remains and thrives when the last stone of the

cottage has fallen, and, by the aid of its underground stolons, spreads

marvellously amid the rubbish.

It is

so rare in Scotland, that many lovers of wild flowers who have searched

the country well-nigh all over, never saw it growing wild. Here its

presence suggests the vanished hand.

Guide-books tell us that, common in England, it thins out toward these

boreal regions. As if it were the most natural thing in the world for a

wild flower, at once so lovely and shelter-loving, to select the shade

and rich depths of southern woodlands.

A

closer acquaintance with its true nature shows the preference to be

rather strange than otherwise. So far from being delicate, it is one of

the hardiest of wild flowers; so far from being a shy woodland plant, it

has no objection to stare the sun in the face.

The

lily of the valley can, on occasion, become the lily of the mountain.

Travellers to Norway find it growing in great abundance on bare rocks,

near the perpetual snow-line.

Like

many another, it may have come too late to the edge of the channel, and

been debarred from crossing by the inflowing of the water. Afterward, it

may have been introduced into English woods, mainly through the gardens;

and much about the same time to the banks of the Tay. Nor are these the

only gifts we owe to the monks; nor the rarest flowers that grow, or

grew but yesterday, around the old monastery of Balmerino. |