|

In the year 1800,

owing principally to this country’s wars with France and Spain, the

average price of wheat per quarter was 113s. 10d.: in 1801 it rose

to 119s. 6d. In 1803, owing to Nelson’s victories, the price

suddenly fell to 58s. 10d., gradually rising again to 126s. 6d. in

1812, when Napoleon was at the height of his power; but falling

again to 65s. 7d. in 1815, the year that Waterloo was fought and

won.

These rapid rises and falls in the price of the principal article of

food must have been very distressful to a country like this, which

cannot support its population entirely from its own soil. But "it’s

an ill wind that blows nobody good”! for “necessity is the mother of

invention”; and to this severe ordeal we can trace the great impetus

given to agricultural improvement in the early part of this century.

Land that had never grown corn was brought into cultivation. Mosses

were drained, limed, and plowed. Hedges and stripes of plantations

were planted for protection and shelter. Schemes and methods of all

sorts were mooted and tried. Some succeeded, some failed, but all

tended to bring experience, and with experience success in the end.

The land-owners, farmers, labourers, lawyers, merchants, doctors,

chemists, clergy, and all sorts and conditions of people, vied with

each other, and gave sound or foolish advice.

The Royal Agricultural Society was the outcome of this fever of

excitement, and taking the matter judiciously up, gave it a

healthier and wiser tone; and, strange as it may seem, the Sheriff

of Hamilton proved one of their most active and successful agents,

and threw himself heart and soul into his work, and trudged on foot

no less than 4000 miles— north, east, south, and west—in all

directions, to gain information from practical and successful

experimentors.

I have read his work with much delight and profit. Copies of it are

now very rare, but Mr James Calder, coal agent in West Calder,

happens to have one, which he prizes much. It is a book I have

quoted from in Chapter I., viz., “Treatise on Mosses, by Wm. Aiton,

Air, 1811.”

West Calder was not behind in this fit of activity. In fact, the

whole east end of the parish was improved and beautified by it.

I am also indebted to Mr Wm. Clarkson, of West Calder, for the loan

of a book, (bought at the Rev. Dr Muckersy’s sale,) which contains a

very interesting account of some of those improvements and their

immediate results, which I will quote for the benefit of the farming

interest. I regret I cannot abridge the article without spoiling it,

for it repeats some things already recorded in these chapters.

The book in question is—“The Literary and Statistical Magazine for

Scotland. Vol. I. Edinburgh: Macready, Skelly & Co. 1817.

Statistical Account of West Calder.

Note.—The Editor has to regret that, from the want of the materials,

he is obliged to delay one or two very important Statistical

articles which he intended to publish in this Number. The following

statements connected with the Parish of West Calder are correct; and

as he is able to give a particular account of the Parish Bank,

instituted in 1807, for which the minister has had many

applications, he trusts that this Statistical Report, though not

completed in the present Number, will be interesting to the public.

Statistical Report of the Parish of West Calder, Presbytery of

Linlithgow, Synod of Lothian and Tweedale, and County of MidLothian.

The parish is bounded by the parishes of Carnwath and Cambusnethan,

in the county of Lanark, on the south-west and west; by Whitburn and

Livingston, in the county of Linlithgow, on the north; by Mid-Calder

on the east; and by Dunsyre and Linton on the south.

Its greatest breadth from north to south, in the line of the

village, which is nearly two miles from the boundry on the east, is

seven miles, and its greatest length from east to west is nearly ten

miles; but the breadth to the west varies from three miles to one.

A continuation of the Pentland Hills, here called “Carin Hills,”

limits the prospect on the south, while the parish stretches

considerably beyond the greatest height of the first range of those

hills. Within this, and also within the Carnwath boundary, lies an

extensive moor, on high ground, for nine miles from south-east to

north west, which, at an average, may be two miles in breadth. This,

after deducting some cultivated acres surrounding a few houses, is

occupied by sheep -farmers, and fit for sheep-pasture alone. The

remaining part of the parish is arable ground.

The soil, west from the village, rests on a stiff tenacious yellow

till, and consists of a thin stratum of black earth mixed with sand.

On the east side of the village the soil is better, and mixed with

clay. The crops chiefly raised are oats, potatoes, rye-grass, ila.x,

and, of late, a few turnips. Barley and pease are now seldom raised

to any extent. Some attempts have been made to raise wheat, but

though nothing was wanting, either in the skill of the farmer or in

the manure employed, they have not been repeated. The expense is

found to be as great as in a kindlier soil, it’ not greater; the

comparative quality may require a reduction of 10 per cent.; the

quantity is less in the proportion of 7 to 10, and the soil, even by

this imperfect crop, is brought nearer to its unimproved state than

in places more adapted to it. The lowness of the rent is the only

thing which can be considered as a compensation for these

disadvantages; but even with this the cultivation of wheat is not

persisted in, the best proof that it is not profitable. No crop,

indeed, in this parish, hay excepted, will pay more than the expense

of rearing it, and the farmers have, therefore, to look to the

produce of the dairy, and to the cattle which they can sell yearly

for their rent.

The hardship under which the farmer labours with respect to corn is,

that when the price is above the average he has little to sell; and

in crops like those of 1782, 1800, and 1816, he has not meal for his

family beyond Whitsunday. Under all these disadvantages the

improvement of this parish has been advancing rapidly for 20 years

past, while the rents, at a general average, have not risen so much

as in a richer soil. The rents here are scarcely doubled, while in

many other places they are four times what they were 30 years ago.

The general tendency to improvement has been impelled here by many

causes. Several proprietors have very judiciously, though at great

expense, improved their own estates. It is not probable that in

every instance they have had a fair rent out of the return; but in

the rapid rise in the value of land, they could have done more than

pay themselves by the sale. The enterprise of the farmers, on the

other hand, has been aided by the great rise in cattle, and on the

produce of the dairy, by the advantage of the Edinburgh market, and

by the opportunity they have of driving coals to the lime kilns, 10

miles off' and bringing lime in return. The lime is used in compost

on lea, and in a few instances among the farmers it is laid on

fallow; but this last, except among the gentlemen improvers, is not

likely to be a general practice.

The average crop of the richest and best cultivated ground in the

parish, taken for four years, may be about six boll3 per acre. The

substantial improvement both in the face of the country and on the

soil, for 20 years past, lias been made by enclosing and planting.

In the judicious manner in which these operations are conducted,

they serve for draining, for shelter, and for ornament. The

principal improvers in these respects, as well as in cultivating the

soil, are Lord Hermand of Hermand, Mr Young of Harburn, Mr

Cunningham of Gavieside, and Mr Mowbray of Little Harwood. A great

deal was also done by the late Mr Davie of Brotherton, and the late

Mr GIoag of Limelield. The estates of these gentlemen, since the

author of this report knew the parish, have been new-modelled and

completely changed. Within these three last years, Mr Douglas, who

resides in London, and is the proprietor of Baads, the most

extensive estate in the parish, has also begun to sub-divide his

farms by belts of planting, sufficiently enclosed.

Among the most enterprising of our heritors are Lord Hermand and Mr

Young of Harburn. The former has improved almost every part of his

estate, and made considerable plantations on the banks of a small

river that runs through liis property, and in most other places

where they can be employed for shelter 01* beauty. Mr Young has done

everything towards the improvement of his property, which wood,

water, and substantial enclosing can accomplish. If others have

clone as much to the improvement of the soil, it must be allowed

that he has done more in making Harbum a finished and delightful

residence.

The following authentic account of his (Mr Young’s) florin deserves

to be recorded. It is taken from his letter to Mr George Rennie, and

published in the Irish Farmers Journal, Sept. 22, 1816. After

several attempts, which were not very successful, he was persuaded

by Dr Robertson to make a trial of raising florin on a piece of very

indifferent land, nearly 20 acres, which the doctor himself

selected; the upper part, exceeding 13 acres, being a dry heathy

moor, the under part 6|- acres of very indifferent moss, not worth a

shilling per acre.

What follows is in his own words :—

“I began paring and burning the upper part of this field in the

common way, but the ashes produced by the operation were by no means

abundant, and the lower or mossy part of the field, I found, could

not be treated in the same manner to any advantage. Resolving to

confine my florin .plantation to the lower part, I got the whole

very carefully trenched a full spade deep, with a proper inclination

towards a large drain; and, for the purpose of covering the surface,

I cut down a small kind of clayey gravel in the irnmediate

neighbourhood, which 1 mixed with ashes from the upper part, and 78

bolls of unslaked lime, spreading the whole on the surface of the

trenched moss, upon which, in spring, 1814, I planted from strings

in the usual way, and it was rolled and occasionally weeded in the

course of the summer.

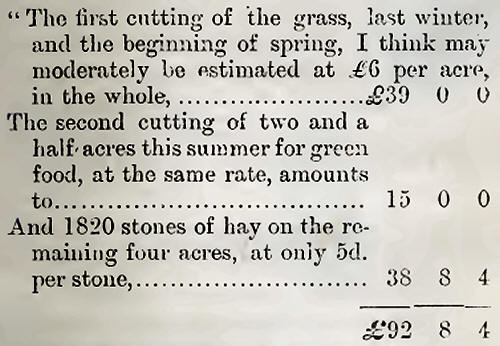

“In the beginning of November last, I began to cut the crop of

grass, and gave it in abundance to my cattle and horses, to whom it

afforded a liberal supply of green food till the end of February

last, with a few short interruptions from the frost and snow. I

cannot tell you what quantity of grass was produced in each acre,

but I can assert with confidence that it was at least equal to a

heavy crop of clover and ryegrass.

“In the beginning of July last, the crop of florin on the 6½ acres,

has again become so luxuriant, that I was induced, contrary to all

instructions from my preceptor, Dr Richardson, to mow it for a crop

of hay, at the same time with the ordinary crop of clover and

ryegrass crops of the country, and it has been treated in exactly

the same way, producing hay, as I think, of a superior quality,

perfectly dry; the same bulk of florin hay, when weighed against

clover and ryegrass, in perfect good order, being uniformly a fifth

less in weight.

“Of the same six acres and a half. I only made four acres into hay,

using the remainder, as I am now doing, for green food. The produce

of the four acres, before it was put up in a stack, was carefully

weighed by John Cay, tenant in Broadshaw, an intelligent fanner, who

attests its weight to be 1820 stones, or 455 tons per acre. The

whole operation oil the field b^ing performed at his sight, I was

desirous that he should also weigh the produce, and see the stack

put up, as he was formerly, when my overseer, a great unbeliever in

the virtues of this grass, though the success of my experiment, I

believe, has now converted him to the florin faith.

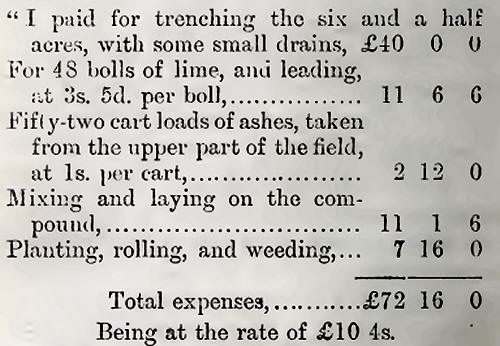

“The expense of trenching was

considerably more than it ought to have been, but it was done with

particular care and attention.

“I intended originally to have given much more lime, but I was

persuaded by a gentleman more skilled in such matters than I

pretended to be, that the above quantity, with the ashes and clay,

was sufficient.

Subject to the ordinary expense of

cutting, making, and Leading home the produce; and I can assure you

that there is no difficulty whatever in mowing the grass with a

scythe. —Harburn, August 19, 1815.”

The Irish mode of burning clay was attempted in this parish in the

summer of 1814. Both the gentlemen improvers and farmers entered

into it with great avidity. It was a proof, if any were wanting, of

the readiness with which Scotch farmers adopt a new plan, when there

is any promise of success. This plan was, however, immediately

abandoned. The tilly subsoil of this parish seems to be altogether

unfit for the operation. There is little doubt, however, in all

cases where paring and burning afford more ashes than is necessary

for the field, that burning the bog, mixed with moss, clay, and

decayed vegetable substances, in the Irish manner, will produce more

ashes, and that they may be used to a better purpose for turnips

elsewhere, than spreading them where they are burned. A prudent

farmer, therefore, may find many detached places on his farm, from

which he may add a few acres yearly to his turnip husbandry, and

leave as much soil in the place from which it is taken as will

permit it to return to grass as before.

These observations, however, are only applicable to places in a farm

where, from the quantity of bog, moss and clay, the produce of ashes

will be much greater than necessary to manure the surface from which

they are taken.

The rent of arable land is from 15s. to 25s. per acre. One or two

farms are let from 28s. to 33s. |