The first attempt at establishing a

stagecoach service in Scotland occurred on 6th August 1678, when the

magistrates of Glasgow entered into an agreement with William Hume, an

Edinburgh merchant, whereby he would "Have in readiness ane

sufficient strong coach, to be drawn by sax able horses, to leave

Edinbro ilk Monday morning, and return again (God willing) ilk Saturday

night". By way of a minor perk, the burgesses of Glasgow

were always to receive preference, so if the coach was full and one or

more of these illustrious gentlemen desired to reach Edinburgh, somebody

had to get off. Since the fare was 4 pounds 16 shillings Scots (8

shillings sterling) in the Summer months and 5 pounds 8 shillings (9

shillings sterling) in the Winter months, it stands to reason that the

sort of individual who could afford the trip would not easily be ejected

from his seat. The first attempt at establishing a

stagecoach service in Scotland occurred on 6th August 1678, when the

magistrates of Glasgow entered into an agreement with William Hume, an

Edinburgh merchant, whereby he would "Have in readiness ane

sufficient strong coach, to be drawn by sax able horses, to leave

Edinbro ilk Monday morning, and return again (God willing) ilk Saturday

night". By way of a minor perk, the burgesses of Glasgow

were always to receive preference, so if the coach was full and one or

more of these illustrious gentlemen desired to reach Edinburgh, somebody

had to get off. Since the fare was 4 pounds 16 shillings Scots (8

shillings sterling) in the Summer months and 5 pounds 8 shillings (9

shillings sterling) in the Winter months, it stands to reason that the

sort of individual who could afford the trip would not easily be ejected

from his seat.

To ensure that the service continued come

what may, the Glasgow magistrates allowed Hume the sum of 200 merks a

year for five years, with two years being paid in advance. Hume's

undertaking was that the coach would run as agreed and without fail

whether or not any passengers required the service. To ensure that the service continued come

what may, the Glasgow magistrates allowed Hume the sum of 200 merks a

year for five years, with two years being paid in advance. Hume's

undertaking was that the coach would run as agreed and without fail

whether or not any passengers required the service.

Unfortunately, Hume's stagecoaching

empire did not last beyond the agreed period and for a long time there

was no regular service. By 1713 the sum total of Scotland's contribution

to the world of coaching were two stagecoaches plying between Edinburgh

and Leith, and a once-a-month coach from Edinburgh to London, which was

twelve to sixteen days on the road, depending on conditions.

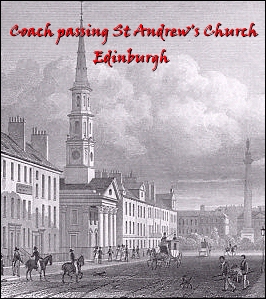

When a service was re-established between

Edinburgh and Glasgow the vehicles, described by those used to southern

coaches as "of the clumsiest construction",

were drawn by four horses in good weather and six in bad. The passengers

almost always had to leave the contraption at the bottom of a hill and

climb on foot until able to join it again. Generally, and unless

anything untoward happened, the journey between the two main cities took

around eleven or twelve hours, progressing at the rate of three and

three-quarters miles per hour, stoppages allowed for. There were two

main stoppages and a variable number of minor ones. Each time the

passengers dined and took tea, and a convention arose that the gentlemen

making the trip always treated the ladies.

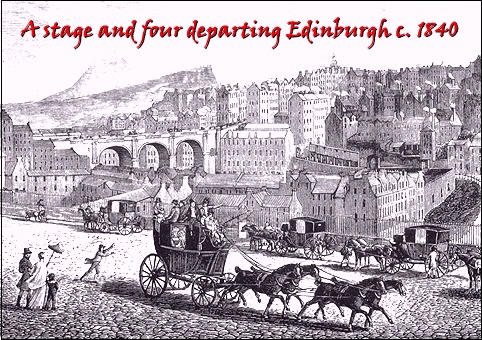

This daily service continued unabated for

almost 30 years, until 1790 when the coaches were replaced by chaises

drawn by two horses. These chaises reduced the travelling time by around

four hours to seven and a half, and by 1799 these were in turn

superseded by improved coaches drawn by six horses and capable of doing

to the trip in six hours. The first of this kind was the Royal

Telegraph, which started on 10th January of that year and was

owned by John Gardner of the Star Inn, Glasgow. This daily service continued unabated for

almost 30 years, until 1790 when the coaches were replaced by chaises

drawn by two horses. These chaises reduced the travelling time by around

four hours to seven and a half, and by 1799 these were in turn

superseded by improved coaches drawn by six horses and capable of doing

to the trip in six hours. The first of this kind was the Royal

Telegraph, which started on 10th January of that year and was

owned by John Gardner of the Star Inn, Glasgow.

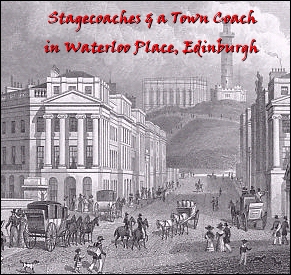

In the years that followed, up until the

advent of the railway in the 1830s, the number of stagecoaches making

the daily run between the capital and the industrial capital increased

to twelve, each carrying between ten and fourteen passengers and

completing the journey in five hours. Also, experiments were carried out

wherein coaches were drawn by two horses and changing six times instead

of four was for a while considered to be the best arrangement, even

reducing the journey time in some cases to three hours and forty

minutes. But the greatest time-saving of all came with the establishment

of the early morning stagecoach, which started at six o’clock and

allowed the passengers to make a return trip in one day. In the years that followed, up until the

advent of the railway in the 1830s, the number of stagecoaches making

the daily run between the capital and the industrial capital increased

to twelve, each carrying between ten and fourteen passengers and

completing the journey in five hours. Also, experiments were carried out

wherein coaches were drawn by two horses and changing six times instead

of four was for a while considered to be the best arrangement, even

reducing the journey time in some cases to three hours and forty

minutes. But the greatest time-saving of all came with the establishment

of the early morning stagecoach, which started at six o’clock and

allowed the passengers to make a return trip in one day.

Although the coming of the railway

largely put an end to the stagecoaches on the Edinburgh to Glasgow run,

other parts of Scotland would remain purely horse-drawn for some time to

come. In the next article we will look at the peculiar problems

besetting those who attempted to establish a transport system in the

Highlands. |