|

IT soon became quite plain that Charles, like his

father and grandfather before him, was bent on making Scotland Episcopalian.

The Presbyterians, seeing this, sent a minister called James Sharpe to

London, to beg the King not to force them to do what they thought was wrong.

But Sharpe betrayed those who sent him. He went over to the King's side,

and, soon after he came back to Scotland, he was rewarded by being made

Archbishop of St. Andrews.

Then Charles ordered all the ministers in Scotland to

become Episcopalian, or to leave their churches. Three hundred and fifty

left, rather than yield. So many churches were thus made empty, that there

were not clergymen enough to fill them. All kinds of ignorant men were then

sent as 'curates,' to preach to the people, instead of their ministers.

These men had 'little learning, less piety, and no sort of discretion,' and

the people would not listen to them. Rather than do that, they followed

their ministers into wild hills and glens, and there, among the heather and

the broom, they sang and prayed as well as in any church.

These meetings were called Conventicles. Conventicle

is formed from two Latin words, con, together, and venire, to come, so that

it means a coming together. To go to a Conventicle was against the law, and

those who did go, went in fear of their lives, for soldiers rode through all

the country looking for such meetings. When they were discovered, the people

were killed, tortured, fined, and ill- treated in every possible way.

Yet the Presbyterians would not give in. The more they

were persecuted, the more they clung to their own form of worship.

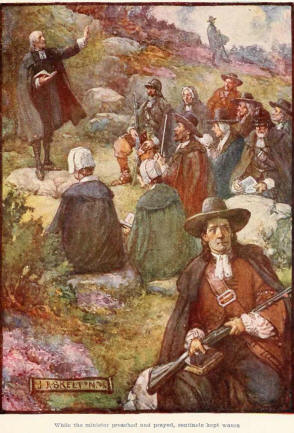

At first people went to the Conventicles unarmed, so

when they were discovered, they were scattered and killed without being able

to resist. But soon they began to arm themselves. Men went to these mountain

churches with guns in their hands, helmets upon their heads, and swords by

their sides. And while the minister preached and prayed, sentinels kept

watch, ready to give the alarm at the first sign of danger.

Among the lonely hills, under the open sky, the voices

of men and women rang out, and the words of the grand old psalms rose

straight to heaven :-

Unto the hills I lift my eves, from whence my help

will grow,

Eve' to the Lord which framed the heavens, and made the deeps

below.

He will not let my feet to slip, my watchman neither sleeps.

Behold the Lord of Israel, still His flock in safety keeps.

The Lord is

my defence, lie doth about me shadow east;

By day nor night, the sun nor

moon, my limbs shall burn nor blast.

He shall preserve me from all ill,

and me from sin protect;

My going in and coming forth He ever shall

direct.'

Then suddenly there is a cry from the watchers.

Through the glen comes the glint of red coats, the gleam of steel.

The women fly for shelter, the men stand to their

arms. The echoes of the hills are awakened by the sound of shots, the clash

of swords, the cries of the wounded. Then silence falls again. All is over.

The soldiers ride away with their prisoners. The lonely valley is once more

still. Only on the trampled blood-stained heather, there lie those who have

walked through the valley of the shadow of death, those who have gone to

dwell in the house of the Lord for ever. Then when evening falls, sorrowing

comrades creep back to lay them in their last resting-place upon the lonely

hill-side.

Many a green spot among the hills was marked with

gravestones, many a peaceful Sabbath morning was turned into a day of

mourning and tears, and at last, maddened by cruelty and oppression, the

Covenanters broke into rebellion. They gathered an army, and about three

thousand marched on Edinburgh. But finding that the people there were arming

against them, they turned aside to the Pentland hills. There, at a place

called Rullion Green, they met the royal troops.

The Covenanters were weary with long marching. They

were hungry and wet. Most of them were but poor peasants, undrilled and

badly armed. But cruelty had made them frantic, and filled with religious

madness they faced the enemy, singing the seventy-eighth Psalm:-

Why art thou, Lord, so long from us,

In all this

danger deep?

Why doth Thine anger kindle thus,

At Thine own pasture

sheep?

Lord, call Thy people to Thy thought,

Which have been Thine so

long;

The which Thou hast redeem'd and bought

From bondage sore and

strong.

Lift up Thy feet and come in haste,

And all Thy foes deface,

Which now

at pleasure rob and waste

Within Thy holy place.

Amid Thy congregation

all

Thine enemies roar, O God!

They set as signs on every well

Their banners splayed abroad.

When wilt Thou, Lord, once cud this shame,

And cease Thine enemies strong?

Shall they always blaspheme Thy name,

And rail on Thee so long?

Why dost Thou draw Thy hand aback,

And hide it in Thy ]ap?

Oh, pluck it out, and be not slack

To give Thy foes a rap.'

The Royalists were led by General Dalyell—Bloody

Dalyell the people called him, because he was so fierce and cruel to the

Covenanters. He was a strange, savage old man. After the death of Charles i.,

be never cut his hair or shaved. his long white beard reached below his

waist, and his clothes were of so quaint a fashion that the children

followed him in the streets to stare at him, as if he were a circus clown.

He had fought in many foreign wars, and now with the psalm-singing was

mingled the sound of strange oaths as the armies closed.

The Covenanters fought with a desperate courage; twice

they beat back the Royalist troops. But the King's soldiers were mostly

gentlemen, well drilled and well armed. The Covenanters were wearied

peasants, and at last they gave way, and fled in the gathering darkness. Not

many were killed in this little battle, but the prisoners who were taken

were put to death with cruel tortures.

In vain Charles tried to crush out the spirit of

Presbyterianism. Middleton, who had ruled for Charles, had been cruel and

bad enough, but after him came the Duke of Lauderdale, a Scotsman, who made

for himself a name to be hated by Scotsmen. He was a big, ugly, coarse,

red-haired man. He hunted, and tortured, and killed the Presbyterians, and

all the time he was a Presbyterian himself!

A terrible Highland army, called the Highland Host,

was now raised and sent against the Covenanters. For three months these wild

mountain men did their worst. They robbed, plundered, and burned, until at

last even their masters grew afraid, and sent them back to their mountains

again. They went back loaded with spoil, as if from the sacking of cities.

Clothes, carpets, furniture of all kinds, pots and pans, silver plate,

anything and everything upon which they could lay hands, they carried off,

leaving their wretched victims penniless, homeless wanderers.

The cruelty and horror of the time at last grew so

bad, that a company of nobles and gentlemen went to London to speak to the

King, and to tell him of the dreadful things which were happening. Charles

listened to what they had to say; then he replied, 'I see that Lauderdale

has been guilty of many bad things against the people of Scotland, but I

cannot find that he has acted anything contrary to my interest.'

So the persecution still went on. Archbishop Sharpe,

the man whom the Covenanters had sent to plead with Charles, had become one

of their bitterest enemies. He helped and encouraged Lauderdale, and at

last, some of the Covenanters, maddened with cruelty and injustice, killed

him as he was driving along a road across a lonely moor.

Many of the Covenanters were sorry for this murder.

But they were all blamed for it, and had to suffer much in consequence. When

they had the chance, and the power, the Covenanters did other cruel and

wicked things. But they were mad, really mad, with suffering. They looked on

all who were not of the Covenant as the enemies of God, and sons of Belial,

and to destroy them was a holy work. So the unhappy years passed on. Now and

again, Charles seemed to try to be kind to the Covenanters. Men there would

come days even more cruel than those that had passed. Many poor wretches

wandered in wild places, living in holes and caves, many fled from the

country and took refuge in Holland. Still the days of battle and blood went

on—the 'killing time' it was called. At last, in 1685 A.D., Charles died.

Charles was clever, but he was a bad man and a bad King. How even his

friends regarded him you can guess from the following lines which were

written by one of them:-

Here lies our sovereign Lord the King

Whose word

no man relies on,

Who never said a foolish thing,

And never did a wise

one.'

|