|

KING JAMES III. was only thirty-five when he was

murdered in 148 A.D., having reigned for twenty-eight years.

The battle did not last long after the King had fled

from the field. The rebels won the victory, and soon after, Prince James was

crowned, under the title of James IV.

But at first no one knew what had happened to James

iii. At this time Scotland was beginning to be famous for her ships and her

brave sea-captains. Sir Andrew Wood, one of the bravest of these

sea-captains, was lying in the Forth with his ships. As the King could be

nowhere found, the lords began to think that perhaps he had taken refuge in

one of Sir Andrew's boats. So they sent messengers to Sir Andrew, asking him

if the King were with him.

'He is not here,' replied Sir Andrew. 'Search my ship

if you do not believe me.'

So the messengers went back. But the Prince and the

lords were not content. They again sent to Sir Andrew commanding him to come

ashore.

Sir Andrew came as he was commanded. He was a very

handsome man, and was grandly dressed. As he came into the room he looked so

splendid that the Prince ran to him crying, 'Sir, are you my father?'

'No,' answered Sir Andrew, the tears running down his

cheeks, 'no, I am not your father. But I was his true servant, and the enemy

of all those who rebelled against him.'

At these words the Prince turned away sadly, for he

had most unwillingly risen against his father.

'Do you know where the King is?' asked the lords sternly, for they did not

like to be spoken of as rebels. I do not,' replied Sir Andrew scornfully.

Still the lords did not believe him. 'Is he not in your ship?' they asked

again.

'He is not,' replied Sir Andrew. 'But would to God he were there safely, and

I should defend and keep him from the traitors who murdered him. I hope to

see the day when they shall be hanged for their evil deeds.'

These bold answers made the lords very angry, and when Sir Andrew had gone

back to his ship, they called all the sea-captains of Leith together, and

ordered them to fight Sir Andrew and to take him prisoner.

But the captains refused, and another brave sailor, called Sir Andrew

Barton, spoke up bravely, 'There are not ten ships in Scotland,' he said, '

fit to fight Sir Andrew's two, for lie is well practised in war, and his men

are hard to beat on land or sea.'

Later, Sir Andrew Wood came to great honour, for James IV. was fond of

ships, and was glad that Scotland should have brave sailors like Andrew Wood

and Andrew Barton.

James saw, too, that it was necessary for Scotland to have a navy. For an

island lying in the sea must have ships to guard her shores, and also to

carry goods to other countries. People were at this time slowly beginning to

learn that a country was richer and happier when at peace, and that it was

much better to trade with other nations, than to fight with them. They were

also finding out that Europe was not the whole world, and many brave sailors

had sailed into far, unknown seas, and discovered strange lands, and had

come home with curious tales of the wonderful countries and peoples they had

seen. So James built ships, and encouraged his people to fish in far seas,

and to trade with distant countries, and soon the Scottish flag was known

and respected far and wide.

Among the ships which James built was one called the Great Michael. It was

the greatest ship that had ever been known. All the carpenters in Scotland

worked upon her for a year and a day, till she was ready to put to sea. All

the forests of Fife were cut down to get wood for the building of this

monster, which cumbered all Scotland to get her to sea, says one old writer.

King James was so interested in this great ship that he used daily to go on

board to watch how the work was going on, and would often dine there with

his lords. At last she was finished, and sailed proudly out on the waters of

the Forth. Then the King commanded that cannon should be fired at her sides,

to see if the vessel was strong enough to stand fire. And the Great Michael

was so well and strongly built, that the cannon did little harm to her.

The English, too, had great ships, and they used to attack the Scots

whenever they met upon the sea. They would even come right up the Scottish

Sea, as the Firth of Forth was then often called. King James was very angry

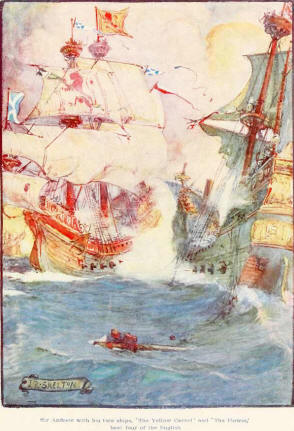

at this, and he sent Sir Andrew Wood against the English; and Sir Andrew,

with his two ships, the Yellow Garvel and the Flower, beat five of the

English, and carried their captains and men prisoner to the King.

When King Henry heard how his ships had been taken, he was very angry. He

sent through all England, saying, that whoever would go to fight Sir Andrew,

and bring him prisoner, should have great honour, and a thousand pounds in

gold. So Stephen Bull, a daring sailor, said that he would go and would

bring Sir Andrew, alive or dead, a prisoner to King Henry.

Stephen Bull, with three great ships, sailed away till he came to the Firth

of Forth. There he found some fishing-boats, whose crews he took prisoner.

Then he sailed on again, but still could see nothing of Sir Andrew. Very

early one summer morning, however, an English sailor on the look-out saw two

ships far away. Stephen Bull made some of the fishermen, whom lie had taken

prisoner, climb the mast, so that they might see whether it was Sir Andrew

or not.

But the fishermen, not wishing to betray their own countryman, said that

they did not know.

'Tell me truly,' said Stephen, 'and whether we win or lose, you shall have

your lives and liberty.'

Then the men confessed that the ships were the Yellow Carvel and the Flower.

Hearing that, Stephen was very glad. He ordered a cask of wine to be brought

up, and all the men and captains cheered, and drank to their victory, of

which they felt sure. Then Stephen sent each man to his post, and prepared

to meet the enemy.

Sir Andrew Wood, on the other hand, came sailing along, little expecting to

meet any English. But when he saw three ships coming towards him in battle

array, 'Ha,' he said, 'yonder come the English who would make us prisoners

to the King of England. But, please God, they shall fail in their purpose.'

He, too, ordered a cask of wine to be brought, and every mail to his fellow,

and, speaking brave words to them, Sir Andrew sent each man to his post.

By this time the sun had risen high, and shone brightly upon the sails. The

English ships were great and strong, and had many guns, but the Scots were

not afraid, and they sailed on towards the English. Soon cannon boomed, and

the fight began. All that long summer day the battle raged, the heavy smoke

darkening the blue sky. The people who lived on the shore watched and

wondered, till at last night fell, and the fighting ceased. But next

morning, as soon as it was light, the trumpets sounded, and once more the

battle began. So fiercely did it rage, that neither captains nor sailors

took heed of where the ships went. They drifted with the tide, and the

fight, which had begun in the Forth, finished near the mouth of the Tay. It

ended in victory for the Scots.

Instead of being taken prisoner to Henry, Sir Andrew took Stephen Bull and

all his men, and led them before King James.

King James thanked and rewarded Sir Andrew greatly, then he sent Stephen and

his men back to England. 'And tell your King,' he said, 'that we have as

manful men, both by sea and land, in Scotland, as he has in England. Tell

him to send no more of his captains to disturb my people. If he does, they

shall not be treated so well next time.'

And King Henry was well pleased neither with the news, nor with the message.

|