|

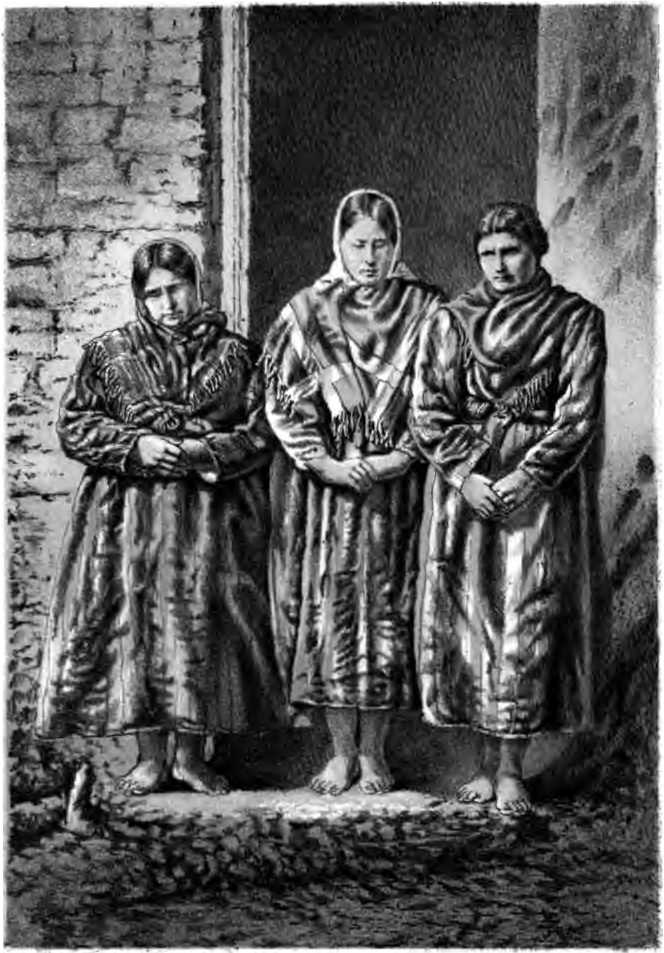

MOST of the writers on St

Kilda give a favourable account of the physical characteristics of the

inhabitants. “Both sexes,” says Martin, “are naturally very grave, and

of a fair complexion; such as are not fair are natives only for an age

or two, but their offspring proves fairer than themselves. There are

several of them would be reckoned among beauties of the first rank, were

they upon a level with others in their dress." The minister of

Ardnamurchan (Macaulay) expresses the same opinion in even stronger

terms. “The women,” he says, “are most handsome; their complexions fresh

and lively, as their features are regular and fine; some of them, if

properly dressed and genteelly educated, would be reckoned extraordinary

beauties in the gay world.” According to the author of ‘Travels in the

Western Hebrides,’ “the women are more handsome, as well as modest, than

those of Harris: they marry young, and address strangers with profound

respect.” He elsewhere states that, owing to the oily nature of their

sea-fowl food the St Kildans “emit a disagreeable odour;” but I am not

aware that this unpleasant characteristic has been referred to by any

recent visitor. Mr Morgan also alludes to the beauties of St Kilda, and

gives a graphic description of the “belle of the island;” but my

correspondent, Mr Grigor, pronounces the women to be “stout and squat;”

and although he admits that many of them have a blond complexion, he

considers them to be generally characterised by “an uncouth comeliness,

which is not very taking.” While Dr Macculloch acknowledges the good

physique of the males, his estimate of the women is not very favourable.

“The men,” he says, “were well-looking, and appeared, as they indeed

are, well fed; exceeding in this, as in their dress, their neighbours of

the Long Island, and bearing the marks of easy circumstances, or rather

of wealth. But the women, like the generality of that little-favoured

sex in this country, appeared harsh in feature, and were evidently

impressed, even in early life, by those marks so dreaded by Queen

Elizabeth, and recorded in the well-known epigram of Plato. This must be

the consequence of exposure to the weather; as there is no want of food

here as a cause, and as the children of both sexes might even be

considered handsome.” The youthful Henry Brougham does not seem to have

been favourably impressed by the appearance of the islanders. “ A total

want of curiosity,” he says, “a stupid gaze of wonder, an excessive

eagerness for spirits and tobacco, a laziness only to be conquered by

the hope of the above-mentioned cordials, and a beastly degree of

filth—the natural consequence of this —render the St Kildan character

truly savage!”

Mr Macdiarmid appears to

have been struck by the fresh-looking, rosy complexions of the

population generally ; the women, however, appearing to him, as they did

to Mr Grigor, to be “more than ordinarily stout.” In the case of both

sexes I observed a good many examples of something more than plumpness;

and I am very much inclined to agree with Captain Thomas in his opinion

that among both men and women there is more than the average amount of

good looks. Traces of a Scandinavian origin seemed to me as apparent

among the natives of St Kilda as in many other parts of the Western

Isles. I believe I came in contact with every inhabitant of the island;

and although I did not make an actual reckoning, I feel satisfied that a

majority exhibit the fair, or Scandinavian, aspect; while the rest are

characterised by the olive complexion, accompanied by dark hair and

eyes, which usually indicates the Celtic type of countenance. The

remarkably healthy look of the children in arms was the subject of

universal comment.

In general appearance,

the natives of St Kilda bear a strong resemblance to the inhabitants of

the Long Island —the men being somewhat less in height, but decidedly

fatter. In respect to weight, they are probably above the national

average, and they are said to lose flesh when placed upon the

comparatively low diet of the inhabitants of the Long Island. Martin

refers to the fact of the generation of his day (1697) having come short

of their immediate predecessors in point of strength and longevity; but

notwithstanding this circumstance, he informs us that “any one

inhabiting St Kilda is always reputed stronger than two of the

inhabitants belonging to Harris or the adjacent isles. Those of St

Kilda,” he continues, “have generally but very thin beards, and those,

too, do not appear till they arrive at the age of thirty, and in some

not till after thirty-five. They have all but a few hairs upon the upper

lip and point of the chin.” He elsewhere tells us that their sight is “

extraordinary good,” and that they can discern objects at a great

distance. Again, in the words of Mr Wilson, “although most of the men

were what we Southrons would call undersized, many of them were stout

and active, and several of them handsome-featured, with bright eyes, and

an expression of great intelligence.” He particularly refers to one of

“even noble countenance —a sort of John Kemble rasd ”—who presented a

picture of activity and strength combined.

Besides alluding to the

strength and healthiness of both sexes, as well as to their capacity for

long-continued exertion, Mr Sands makes special mention of the

brightness of their eyes and the whiteness of their teeth. The average

height of twenty-one male adults whom he measured was about five feet

six inches—the tallest being five feet nine inches, and the shortest

four feet

ST KILDA MAN.

ten and a half inches. In

addition to a woman who is subject to fits, and an aged male of weak

intellect, but quiet and peaceable when not contradicted, and who lives

by himself in one of the old thatched hovels, there is an elderly man

who lost his sight about six years ago. The poor imbecile contrives to

cultivate a small patch of ground, and to accompany his neighbours to

the fishing; while his blind brother-islesman sits cheerfully at his

cottage door, and is still able to sew and make gins. With these three

exceptions,- all the other members of the little community are at

present sound in both body and mind. In allusion to her recent visit to

the island, the “Bartimeus” of St Kilda said to Miss Macleod that “as

Solomon did not go to see the Queen of Sheba, the Queen of Sheba kindly

came to see Solomon! ”

Mr Wilson describes the

prevailing Dress of the males as very similar to that of the fishermen

of the Long Island—“small flat blue bonnets, coarse yellowish-white

woollen jerkins, and trousers, also of coarse woollen stuff, of a mixed

colour, similar to that of heather stalks.” Mr Muir informs us that he

found both males and females very decently and comfortably clothed, and,

in that respect at least, presenting a very favourable contrast to their

equivalents in the Western Islands generally. “ The dress of the

females,” he says, “has some peculiarities, the which it would be

difficult for any but a man-milliner, or one of their own sex, to

describe. A suit, consisting of a round coat, waistcoat, and trousers,

made of the coarse kelt manufactured from the short wiry wool of their

native sheep, and fashioned very much as such things are in the

Lowlands, is the dress universally worn by the men. Even among the

children we did not see a single kilt”

According to Martin, the

ancient habit of the St Kildans was of sheepskin, which, he says, “has

been worn by several of the inhabitants now living. The men at this day

(1697) wear a short doublet reaching to their waist, about that a double

plait of plad, both ends joined together with the bone of a fulmar. This

plad reaches no further than the knees, and is above the haunches girt

about with a belt of leather” (apparently an approach to the modern

kilt). “They wear short caps of the same colour and shape as the

Capuchins, but shorter; and on Sundays they wear bonnets. Some, of late,

have got breeches, which are wide and open at the knees. They wear cloth

stockings, and go without shoes in the summer time. Their leather is

dressed with the roots of tor-mentil. The women wear upon their heads a

linen dress, straight before, and drawing to a small point behind, below

the shoulders, a foot and a half in length; and a lock of about sixty

hairs hanging down each cheek, reaching to their breasts, the lower end

tied with a knot. Their plad, which is the upper garment, is fastened

upon their breasts with a large round buckle of brass, in form of a

circle. . . . They wear no shoes or stockings in summer; the only and

ordinary shoes they wear are made of the necks of solan geese, which

they cut above the eyes; the crown of the head serves for the heel, the

whole skin being cut close at the breast, which end being sewed, the

foot enters into it, as into a piece of narrow stocking. This shoe doth

not wear above five days, and, if the down side be next the ground, then

not above three or four days. . .' . Both sexes wear coarse flannel

shirts, which they put off when they go to bed.”

Lane Buchanan informs us

that the St Kildans “are possessed of an equal share of pride and

ambition of appearing gay on Sundays and holidays with other people;”

while Macculloch refers to the remarkable fact of a community so remote

having entirely conformed to the Lowland garb. “Not a trace of tartan,

kilt, or bonnet was to be seen; so much has convenience gained the

victory over ancient usage. The colours of the breachan might indeed

have still been retained: but all was dingy brown and blue.” Speaking of

the rapidity with which “fashion” travels, he elsewhere mentions that a

peculiar kind of shoe-string, which had been invented in London during

spring, had reached the distant shores of St Kilda by the following

summer. Bonnets have for some time been considered essential for full

dress by the female islanders; and the graceful handkerchief fastened

under the chin is said to be looked upon as vulgar! When the Rev. Neil

Mackenzie went to the island in 1830, his servant-maid, a native, asked

permission to take the hearth-rug to church, by way of a shawl.

Regarding her proposal as a joke, he innocently assented; and to his

infinite astonishment he beheld the girl in his own pew, enveloped in

the many-coloured carpet, the envied of an admiring congregation! All

the women in the island were eager candidates for the “ shawl ” on the

following morning, some of them offering to give “ten birds” for its

use.

Mr Macdiarmid supplies

the following account of the Sunday dress1 of

the St Kildans: “The men wore jackets and vests of their own making,

mostly of blue colour, woollen shirts, a few had linen collars, and the

remainder cravats on their necks; the prevailing headdress was a broad

blue bonnet The women’s dresses were mostly home-made, of finely spun

wool, dyed a kind of blue and brown mixture, and not unlike common

wincey. Every female wore a tartan plaid or large shawl over her head

and shoulders; and upwards of twenty of these plaids were of Rob Roy

tartan, all from the mainland. They were fastened in front by an

antiquated-looking brooch. Several of the women wore the common white

muslin cap or mutch; and I noticed one solitary bonnet, of romantic

shape, adorning the head

ST KILDA WOMEN.

of by no means the

fairest-looking female present. All the men, and a few of the women,

wore shoes; the rest of the women had stockings, or went barefooted.” Mr

Sands informs us that “ the men all wear trousers and vests of coarse

blue cloth, with blanket shirts. On Sundays, they wear jackets in

addition. Their clothes are made at hftme from wool plucked (not shorn)

from their own sheep, which is spun by the women with the ancient

spindle or more modern wheel. The women also dye the thread, and the men

weave it into cloth, and make it into garments for both sexes. The dress

of the women consists of a cotton handkerchief on the head, which is

tied under the chin, a gown of coarse blue cloth, or blue with a thin

purple stripe, fastened at the breast with an iron skewer.” (He

elsewhere says, “ with a large pin made from a fish-hook.”) “ The skirt

is tied round the waist, and is girded tightly above the haunches with a

worsted sash of divers dim colours,1 and is worn very short—their

muscular limbs being visible from near the knee. They wear neither shoes

nor stockings in summer. They go barefoot even to church; and on that

occasion don a plaid, which is worn square, and fastened in front with a

copper brooch, like a small quoit, made by the men from an old penny

beat out thin. All the women’s dresses are made by the men, who also

make their brogues or shoes ; for every female owns a pair, although she

prefers going without them in summer. . . . The brogues are sewed with

thongs of raw sheepskin, and look like clumsy shoes. The ancient

Highland brogue, which was open at the sides to let out the water, was

in use until a few years ago.” The same writer refers to the entire

absence of ornament in all their works, thereby differing from the

ordinary Highlander. “The only exception,” he says, “ to this, is in

some of their woollen fabrics, where there is a feeble attempt at colour.

And yet they seem fond of bright colours. But everything else appears

designed solely for utility. The women's brooches are perfectly plain,

and the large pins that fasten their gowns mere skewers. There are no

Celtic traceries or *uncouth sculptures ’ on their tombstones, or on any

building, or any attempt at wood-carving in boat or in house. The

aesthetic faculty, if it exists, seems never to have been developed.”

In Martin’s time, the

ordinary Food of the inhabitants of St Kilda appears to have been barley

and “ oat-bread baked with water,” fresh beef and mutton, and the

various kinds of sea-fowl, which were merely dried in the small stone

houses or “pyramids” erected for the purpose, without any salt or spice

to preserve them. With their fish and other food, they still use an

oleaginous accompaniment prepared from the fat of their fowls, termed

“giben,” also in a fresh state. It is melted down and stored in the

stomachs of the old gannets, like hog’s-lard in bladders. “They are

undone,” says Martin, “for want of salt, of which as yet they are but

little sensible. They use no set times for their meals, but are

determined purely by their appetites.” In one of his letters to the ‘

Scotsman/ Mr Sands states that the islanders usually dine as late as

five or six o’clock. That hour appears to be found the most suitable, in

consequence of their continuous absence—on fowling expeditions and other

avocations— during the greater part of the day. Martin made particular

inquiry respecting the number of solan geese consumed by the inhabitants

during the preceding year, and ascertained that it amounted to 22,600,

which he was informed was under the average. At that time, the common

drink was water or whey. According to the same writer, “ they brew ale

but rarely, using the juice of nettle-roots, which they put in a dish

with a little barley-meal dough. These sowens (t. e., flummery) being

blended together, produce good yeast, which puts their wort into a

ferment and makes good ale, so that when they drink plentifully of it,

it disposes them to dance merrily.”

Mr Wilson states that the

St Kildans are frequently very ill off during stormy weather, and at

those periods of the year when the rocks are deserted by their feathered

occupants. “Their slight supply of oats and barley,” he says, “would

scarcely suffice for the sustenance of life; and such is the injurious

effect of the spray in winter, even on their hardiest vegetation, that

savoys and German greens, which with us are improved by the winter’s

cold, almost invariably perish soon after the close of autumn. . . . The

flesh of the fulmar is a favourite food with the St Kildans, who like it

all the better on account of its oily nature. With it and other

sea-fowl, they boil and also eat raw a quantity of sourocks, or

large-leaved sorrel—a sad and watery substitute for the mealy potatoes

of more genial climes. But happy it is for those who, like many a poor

St Kildan, know and remember that *man does not live by bread alone.”

In his extracts from Mr Mackenzie’s Journal, we find the following

statement relative to the privations of the islanders during the month

of July 1841: “The people are suffering very much from want of food.

During spring, ere the birds came, they literally cleared the shore not

only of shell-fish, but even of a species of sea-weed that grows

abundantly on the rocks within the sea-mark.

“The flesh of puffins is

not only extensively used as food by the Icelanders, but it is also

considered to be the best of bait for cod-fish. Puffins are in great

repute for their feathers in Norway, and also for their flesh in some

country parts. Yet if the natives could read what Wecker (quoted in the

‘ Anatomy of Melancholy ’) says of such food, they would avoid these

melancholic meats.’ ‘ All finny fowl (he says) ‘ are forbidden ; ducks,

geese, and coots, and all those teals, curs, sheldrakes, and freckled

fowls that come in winter from Scandia, Greenland, etc., which half the

year are covered up with snow. Though these be fair in feathers,

pleasant in taste, and of a good outside, like hypocrites, white in

plumes and soft, yet their flesh is hard, black, unwholesome, dangerous,

melancholy meat.* . . . Puffin-pie sounds like an abomination, but it is

not bad if properly cooked. Experto crede. The backbone must be removed,

and the bird soaked in water for some hours before cooking it, or it

will taste of fish. Many seabirds are excellent eating, if this

precaution is observed. For instance, a cormorant roasted and eaten with

cayenne and lemon, is nearly as good as a wild duck, and better than a

curlew. A fisherman of my acquaintance has often told me that ‘a fat

gull is as good as a goose any day.’ ”—Elton’s Norway, pp. 92-94.

For a time then they were

better off, particularly as long as fresh eggs could be got. Now the

weather is coarse, birds cannot be found, at least in such abundance as

their needs require. Sorrel boiled in water is the principal part of the

food of some, and even that grass is getting scarce. All that was near

is exhausted, and they go to the rocks for it, where formerly they used

to go for birds only.”

Mr Wilson refers to

Macaulay’s important inquiry as to “whether St Kilda be a place proper

for a fishery? ” and reasonably concludes, from the enormous number of

sea-fowl, that the surrounding waters must be well stocked with fish.

According to Martin, the coasts of St Kilda and the lesser isles are

plentifully furnished with “ a variety of cod, ling, mackerel, congars,

braziers, turbot, greylords, and sythes; . . . also laiths, podloes,

herrings, and many more. Most of these are fished by the inhabitants

upon the rock, but they have neither nets nor long-lines. Their comfhon

bait is the lympets or patella, being parboiled ; they use likewise the

fowl called by them bouger (puffin), its flesh raw, which the fish near

the lesser isles catch greedily. Sometimes they use the bouger’s flesh

and the lympets at the same time upon one hook, and this proves

successful also.” Mr Wilson estimates the number of solan geese alone in

the colony of St Kilda at 200,000, their favourite food being herring

and mackerel; and, on the assumption that each of them is a feeding

creature for seven months in the year, he computes the summer sustenance

of this single species at no less than 214 millions of fish!1 “ Think of

this,” he remarks, “ye men of Wick, ye curers in Caithness, ye fair

females of the salting-tub. It is also a subject of very grave

consideration by all who take an interest in the forlorn St Kildans. A

second boat” (he adds) “would probably be of great advantage, and also a

good supply of hooks and lines.”

Mr Grigor considers the

St Kildans to be much better off, according to their habits of life,

than is generally supposed ; and Mr Kennedy, the catechist, assured him

that every one of them had some money laid past Captain Thomas informs

me that, in the year i860, they were able to pay a half-year’s rent in

advance. According to Mr Grigor, “ their food is principally the flesh

of marine birds—the gannet, fulmar, and puffin—of which the two first

are stored for the winter. They do not care for farinaceous food or

fish. They also eat mutton and beef in emergencies, and milk and eggs

always. There is plenty of good ling and cod to be got about the

islands, and the people have begun to cure.” For that purpose an

abundant supply of salt appears to be a great desideratum. In i860,

Captain Otter of the “ Porcupine”—engaged on the Admiralty

Survey—brought off sixteen cwt of excellent fish, which were sold for

^16, and the proceeds given to the inhabitants. About twelve years ago,

some of the younger men having resolved to fish, procured a suitable

boat and lines ; and at that time it was considered that, if no disaster

should occur, they ought to catch from three to four tons of fish, which

would be worth upwards of £50.

According to the ‘Fishing

Gazette' this is equal to 305,714 barrels, or much more than the total

average of herrings branded at all the north-east stations. To the

number indicated must be added what the cod and dogfish and other fowls

and fishes devour. The fruitfulness of the herring to balance this

enormous destruction by man, fish, and fowl is correspondingly great, as

the roe generally contains between 60,000 and 70,000 eggs.

According to Lane

Buchanan, the guillemot supplies the wants of the St Kildans when their

fresh mutton is exhausted. “Then the solan goose is in season; after

that the puffins, with a variety of eggs ; and when their appetites are

cloyed with this food, the salubrious fulmar, with their favourite young

solan goose (called goug), crowns their humble tables, and holds out all

the autumn. In winter they have a greater stock of bread, mutton,

potatoes, and salad, or reisted [salted] fowls, than they can consume.”

While the sea-birds are eaten in a fresh state during summer, they are

salted for consumption in winter. I have somewhere seen the number so

salted stated at 12,000, which is equal to about 150 birds for every

man, woman, and child. Mrs M'Vean mentions that every family has about

three or four barrels of fulmars salted for winter use, the flavour of

which she considers similar to that of salted pork. Their principal food

in summer is roasted puffin. “ For breakfast,” she observes, “ they have

some thin porridge or gruel, with a puffin boiled in it to give it a

flavour. Dinner consists of puffin again, this time roasted, with a

large quantity of hard-boiled eggs, which they eat just as the peasantry

eat potatoes; They use no vegetables, except a few soft potatoes, not

unlike yams. They consume very little meal, as their crops are not good,

and are liable to being swept off by the fierce equinoctial gales. ;

Bread is considered a great luxury, and is only used at christenings,

weddings, and the New Year. The latter is quite a time of feasting, as

each family kills a sheep, and bakes oatmeal cakes. The principal drink

is whey. No vegetables can be raised (as in Martin’s time), owing to the

showers of spray that dash over the island. Even kail plants are with

difficulty reared.”

Mr Sands also states that

“the St Kildans subsist chiefly on sea-fowl, the flesh of the fulmar

being preferred. This they eat both in a fresh and in a pickled

condition. The men when out in their boats dine on oat-cakes and

ewe-milk cheese, washed down with milk or whey. The women when herding

use the same viands. The sea-fowl must be nutritious, judging from, the

lusty looks, strength, and endurance of the people. They have a

prejudice against fish, and use it sparingly, alleging that it causes an

eruption on the skin. They care little for tea, but are fond of sugar,

and the women are crazy for sweets. The men are equally fond of tobacco,

although they consume it little, probably because it is too costly.”

Mr Macdiarmid specifies

the following as the ordinary diet of a St Kildan :—

Breakfast.—Porridge and

milk.

Dinner.—Potatoes, and the

flesh of the fulmar, or mutton, and occasionally fish.

Supper.—Porridge, when

they have plenty of meal.

He also mentions that

they take tea once or twice a week, and appear to be rather fond of it

“They seemed surprised,” he adds, “at the small quantity of tea sent to

them in proportion to the amount of sugar.” While he confirms Mr Sands’s

statement regarding the fondness of the men for tobacco, he says that he

“saw no signs whatever of the partiality for sugar and sweets which has

been attributed to them.” I believe, however, that, in common with the

other islanders of Scotland, and especially the Shetlanders, the

inhabitants of St Kilda have a very decided weakness for sweets. On the

occasion of my recent visit, in addition to a number of showy

picture-books for the children, I took a supply of sweets, for both

adults and juveniles, in the shape of peppermint-drops and “gundy” — a

species of strongly-flavoured “rock” — having previously ascertained, on

the best authority, that these two confections would be especially

acceptable; and judging from the demonstrations which accompanied the

distribution, the common opinion regarding the penchant in question

seemed to be fully corroborated. The large quantity of salt food

consumed by the St Kildans during winter has been suggested as the

possible cause of their addiction to sweets. Teetotalism does not appear

to have reached St Kilda. Mr Grigor partook of both wine and whisky at

the house of the cate-chist, and he was informed that some spirits were

to be found in every household—being only used, however, “on great

occasions, or medicinally.”

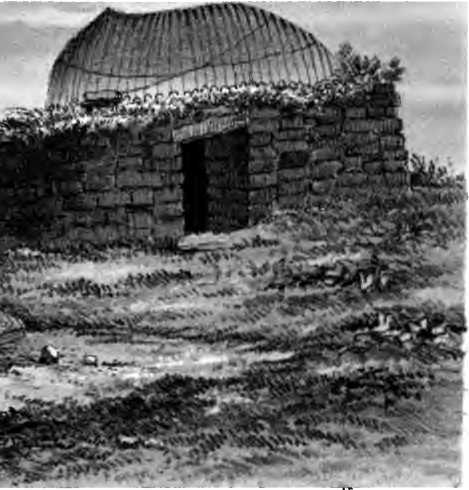

In Martin’s time, the St

Kilda Houses were of a low form, rounded at the ends, and with all the

doors to the north-east, to secure them from the tempestuous shocks of

the south-west winds. The walls were rudely built of stone, and the

roofs—of wood, covered with straw—secured by ropes of twisted heather,

to prevent the thatch from being carried away by the gales. They were

built in two rows, with a causeway between called “ the street” Mr

Wilson believes that the houses which existed up to the beginning of the

reign of George IV. were the same as those in which the inhabitants had

lived during the entire period of their authentic history. He describes

these primitive dwellings as consisting of “ a low narrow entrance

through the thick stone wall, leading to a first apartment, in which, at

least during the winter season, were kept the cattle; and then to a

second, in which the natives dwelt. These inner rooms, though small,

were free from the incumbrance of beds, for the latter were placed in,

or rather formed by deep recesses of the walls, like low and horizontal

open presses, into which they This primitive practice is referred to by

both Herodotus and Juvenal. crept at night, their scanty bedding being

placed upon stones, in imitation of the puffins.”1 The same author

attributes the improved system of house-building to an accomplished and

liberal Englishman, Sir Thomas Dyke Acland, who visited the island in

his yacht upwards of forty years ago, and left a premium of twenty

guineas with the minister (the Rev. Neil M'Kenzie) for the first person

who should demolish his old house and erect a new one on an improved

principle. A tenacious adherence to uniformity had long formed a

characteristic feature in the social polity of the inhabitants, and it

was some time before any one was bold enough to take a step in advance.

At length a comparatively energetic individual commenced the double work

of demolition and reconstruction, which resulted in a general movement;

and under the judicious superintendence of the worthy minister, “ the

ancient city of St Kilda was razed to its foundations, and one of modern

structure erected in its place.” When Mr Wilson visited the island in

1841, only a single roofless hut of the olden time remained to

illustrate the peculiar construction of these rude dwellings.

There are at present

eighteen inhabited houses on the island—viz., sixteen cottages with zinc

roofs, and two thatched huts, arranged in the form of a crescent, from

fifteen to twenty yards apart, and numbered from right to left. The

occupants of each of the cottages range from two to seven, while the two

huts are respectively tenanted by a bachelor and a spinster. The

cottages were built about fifteen years ago by Sir John Mac-pherson

Macleod, the late proprietor of St Kilda. Most of the other old huts

still stand, alternating with the cottages, and are used by the

inhabitants as byres and cellars.2 They are constructed of rough stones,

without mortar. The walls are of great thickness, varying from five to

eight feet, and about five feet high on the outside; or, rather, they

really consist of two strong dykes within a foot or two of each other,

the intermediate space being tightly packed with earth, so as to fill up

all the interstices. The doorway is very low—somewhere about three feet

in height—and in consequence of the great thickness of the double walls,

the entrance may be almost termed a passage, resembling, in miniature,

that of the celebrated Maeshowe in Orkney. The shape of the huts is

oval, and internally they are divided into two apartments by a removable

partition of loose stones. Most of them can boast of a small four-paned

window, which, however, admits a very limited amount of light, in

consequence of the great thickness of the walls. The door is secured by

a wooden lock, worked with a key of the same material.

COTTAGES.

and of ingenious

construction. “One feature,” says Mr Muir, “belonging to the houses

rather amused us. On our return from the day’s excursion, the people

being assembled in the church, we found the doors in most instances

secured by a large wooden lock, so ingeniously contrived that we were

utterly unable so much as to conjecture by what means it could be

opened. The thing, made up of a square of several sturdy bars immovably

jammed, ends and sides together, and without catch or keyhole, was

certainly a puzzle that would have honoured a Chubb or a Chinaman. Yet

more puzzling than the lock seemed the necessity for its existence.”

The roofs, which are of

thatch, are circular or somewhat rounded, and are secured by ropes of

straw with heavy stones attached to their extremities, as in many other

parts of the Hebrides, for the purpose indicated by Martin. Instead of

the thatch projecting beyond the walls, in accordance with the ordinary

practice, its edge springs from the inner side of the thick wall, and

thus counteracts the effects of the wind. In the case of a few of these

old houses, the walls contain boot-shaped vaults or recesses, similar to

those described by Martin, which were formerly used as beds, and which

are accessible through small apertures, about two feet from the floor,

resembling the mouth of a baker's oven. One of these, which I inspected

with the aid of a light, was certainly not very inviting. The fireplace

used to occupy the middle of the room, being a circular cavity in the

floor, round which the natives sat before smouldering ashes of dry turf,

cut or scraped together from the hills. Most of the smoke made its exit

through the doorway; but, owing to the scarcity of fuel, the smoke was

not very troublesome. The absence of chimneys, however, was to some

extent compensated for by the accumulation of soot on the under side of

the thatch. . Once a-year, usually in May—as is still the practice in

Lewis and other parts.of the Hebrides —the huts were unroofed, in order

to remove the lower portion of the sooty straw for the purpose of

manure, and in October a fresh coating of thatch was laid upon the part

that remained. The want of peat in St Kilda makes a glowing fire a rare

spectacle. Occasionally a log or other fragment of wood is cast upon the

island; but owing to the limited extent of shore, such godsends are not

very frequent The memoranda furnished to Mr Wilson by the Rev. Neil

M'Kenzie contain several allusions to the scarcity of fuel. Sometimes

when the islanders run short of turf, they are compelled to burn grass (phiteach)

as a substitute. In referring to the important subject of fuel, Mr

Macdiarmid very naturally speculates on the probable result of the

present disastrous but apparently unavoidable system of stripping the

turf from the pasture as a substitute for peat Many hundreds of acres

have already been thus bared; and only where a little soil is left on

the surface of the rock is there anything like an approach to the

original sward. In other parts of the Western Isles, such as Iona,

Tyree, and Canna, the deficiency of fuel is a very serious circumstance.

The author of the ‘Agriculture of the Hebrides’ says that “the man who

opens a colliery in the Hebrides, or opposite the mainland of the west

of Scotland north of Cantyre, will confer a greater favour on those

sequestered regions than the whole dictionary of praise can express. He

will literally kindle the flame of gratitude, and ‘ cheer the shivering

native’s dull abode.’ ”

Mr M'Kenzie gives the

following account of the domestic usages of the St Kildans, as they

continued up to a comparatively recent date (1863), when they took

possession of their present abodes: “The apartment next the door (as in

Martin’s time) is occupied by the cattle in winter, and the other by

themselves. Into their own apartment they begin early in summer to

gather peat-dust, which they use with their ashes, and moisten by all

the foul water used in making their food, etc. By these means the floor

rises gradually higher and higher, till it is, in spring, as high as the

side-wall, and in some houses higher. By the beginning of summer a

person cannot stand upright in any of their houses, but must creep on

all fours round the fire."

The modern cottages,

which, as already stated, were erected by the late proprietor of the

island in 1861-62, present a favourable contrast to these squalid

abodes, and in respect of house accommodation, the St Kildans may now be

regarded as far ahead of the inhabitants of the Long Island. Mr

Macdiarmid furnishes the following detailed account of their

construction: “The walls are well built, with hewn stones in the

corners, and about seven or eight feet high; chimney on each gable; roof

covered with zinc; outside of walls well pointed over with cement, and

apparently none the worse as yet of the many wild wintry blasts they

have withstood. Every house has two windows, nine panes of glass in

each, one window on each side of door; good, well-fitting door, with

lock. The interior of each house is divided into two apartments by a

wooden partition, and in some a bed-closet is opposite the

entrance-door. Every house I entered contained a fair assortment of

domestic utensils and furniture—kitchen-dresser, with plates,6

bowls, pots, kettles, pans, etc., wooden beds, chairs, seats, tables,

tin lamps, etc. There is a fireplace and vent in each end of the house,

which is certainly an improvement on the majority of Highland cottars’

dwellings, where the fire is often on the middle of the floor, and the

smoke finds egress by the door or apertures in the wall, or it may be a

hole in the roof.” The zinc plates are nailed down over wooden planks.

The minister told Dr Angus Smith that he considered the roofs to be a

failure, “ since it rained inside whenever it rained outside,” the

plates not being made to overlap sufficiently to produce perfect

security. When the inhabitants first took possession of these new

houses, they found them colder as well as airier than their former

abodes; but this is the ordinary experience among the humbler classes,

when they are persuaded to occupy improved dwellings. At the time of Mr

Wilson’s visit to St Kilda in 1841, the furniture was very scanty, each

house then having “ one or more bedsteads, with a small supply of

blankets, a little dresser, a seat or two with wooden legs, and a few

kitchen articles.” About twelve years later, an assortment of crockery

was furnished to the islanders by the Rev. Dr M'Lauchlan and a small

party of friends, on the occasion of an expedition to St Kilda; and

before they left the island, they were not a little amused to find

certain utensils, to which I cannot more particularly allude, freely

used as porridge-dishes!

On the 3d of October i860

a dreadful storm swept across St Kilda, and the roofs of some of the

houses were carried away by the gale. A large sum was collected in

Glasgow to provide for the destitution which it was believed to have

occasioned, and it was proposed to devote a portion of the fund to the

erection of new houses. It appears, however, that this was opposed and

prohibited by the proprietor, who himself sent masons and carpenters

from Skye the year following, for the purpose of building four houses,

each containing two rooms and two closets.

Besides the cottages of

the islanders, the little township of St Kilda embraces four other

fabrics of a more pretentious kind—to wit, the manse, church,7

store, and factor’s house. Situated on the north-east side of the bay,

about a hundred yards from the beach, and twice that distance from the

village, the manse is a one storeyed, slated building, with a porch, and

contains four apartments. It is protected on one side by a high wall by

way of shelter, and in front is an enclosed patch of tilled-ground,

where a rain-gauge is placed. On looking into the rooms* I was struck by

their unfurnished and comfortless aspect— the absence of a helpmate

being painfully apparent. The manse must have presented a better

appearance at the time of Mr Wilson’s visit. He describes the apartment

in which he was received by the minister as “ a neat enough room,

carpeted, and with chairs and tables, but with some appearance of damp

upon the walls, which, on tapping with our knuckles, we found had not

been lathed.”

At the same period, the

minister—or rather the prime minister—of St Kilda was the Rev. Neil

Mackenzie, now pastor of Kilchrenan, Argyllshire, who also acted in the

capacity of teacher, and who appears to have done everything in his

power to improve both the spiritual and physical condition of the

inhabitants. Some interesting extracts from his MS. memoranda relative

to the weather, the condition of the people, and the arrival of the

various sea-fowl, to which I have already referred, are printed in Mr

Wilson’s work.

The church, built at a

cost of about £600, is situated immediately behind the manse—a plain,

substantial structure, with a door and four windows. Like the manse, it

has a slated roof, but only an earthen floor—the pews consisting of rude

deal benches. On each side of the pulpit, which is accompanied by the

ordinary precentor’s desk, is an enclosed pew, of which one is for the

use of the elders, and the other for visitors. Two wooden chandeliers,

recently presented by Sir Patrick Keith-Murray, are suspended from the

ceiling, each charged with three excellent candles made from the tallow

of the sheep; and the islanders are summoned to worship by a small bell

which was recovered from a wreck.

The little burial-place,

elliptical in form, and surrounded by a wall, is situated behind the

village, and, like most Highland churchyards, is overgrown by nettles,

and otherwise in a very neglected condition. A better state of matters

appears to have prevailed at the close of the seventeenth century.

Martin says,—“They take care to keep the churchyard perfectly clean,

void of any kind of nastiness, and their cattle have no access to it”

With the solitary exception of a slab, erected by a former minister,

none of the tombstones bear any inscriptions. The ruins of one of the

ancient chapels—removed a few years ago—occupied the centre of the

burial-ground. One of the stones bearing an incised cross, which I

unfortunately neglected to look for, is built into the wall of a

cottage. Gray’s well-known lines seem peculiarly applicable to the

“God’s acre” of St Kilda

“Perhaps in this neglected

spot is laid

Some heart once pregnant with celestial fire;

Hands that the rod of empire might have swayed,

Or waked to ecstasy the living lyre:

But Knowledge to their eyes her ample page

Rich with the spoils of time did ne’er unroll;

Chill penury repressed their noble rage,

And froze the genial current of the soul.

Full many a gem of purest ray serene

The dark unfathomed caves of ocean bear :

Full many a flower is born to blush unseen,

And waste its sweetness on the desert air.”

Close to the

landing-place is the store, built of stone and lime, and with a slated

roof, in which feathers and oil—the staple exports of the island—are

deposited; and in its immediate neighbourhood is another very tolerable

house, resembling the manse in form, in which the factor resides during

his periodical sojourns. On the occasion

of my visit, we found

that it had been occupied, for upwards of a fortnight, by Miss Macleod

of Macleod, the sister of the proprietor of St Kilda, who returned with

us in the “Dunara.” As already mentioned, she had accompanied Lord and

Lady Macdonald in their yacht on the 15th of June, and had spent sixteen

days on the island, with the view of making herself acquainted with the

condition of the inhabitants. The scene at her departure was not a

little touching. While she was affectionately kissed by the women, the

men “lifted up” their voices. I was, however, fully prepared for this

display of attachment, having heard so much of the benevolent lady’s

acts of kindness at Dunvegan, where a woman, to whom I happened to speak

of Miss Macleod’s absence from Skye being a cause of regret in that

quarter, warmly informed me that she was “an angel in human form! ” |