|

| |

|

Biographical Sketch of

Robert Stevenson

Civil

Engineer, by Alan Stevenson (1851) |

|

Robert Stevenson was

born at Glasgow on the 8th June 1772, and died at Edinburgh on the 12th

July 1850, in the seventy-ninth year of his age. His father, Alan

Stevenson, was a partner in a West India House in Glasgow, and died in

the island of St Christopher, while on a visit to his brother, who

managed the business abroad. His only son Robert, the subject of this

memoir, was then an infant, and, with his mother, was ultimately left in

circumstances of the greatest difficulty; for the same epidemic fever

which deprived him of his father carried off his uncle also, at a time

when his loss operated most disadvantageously on the business which he

had superintended, and very many years elapsed before any funds in which

my father had an interest were realised. His mother's circumstances now

compelled her to take advantage of a charity school for him during his

infancy; and the high spirit of the man is well brought out by the fact

that he devoted his first earnings in life, at the Cumbrae Lighthouse,

to the repayment to that institution of what he viewed as a debt. In

this manner was my father's early education conducted, although, as the

sequel shows, with success, yet under circumstances which could not by

any means be called favourable. This success was chiefly due to the

energy of his mother, Jane Lillie, who was a woman of great prudence and

remarkable fortitude, based on deep convictions of religion. It appears,

from some memoranda left by my father for the information of his family,

that his mother had intended him for the ministry, with a view to which

he had been sent to the school of a famous linguist of his day, Mr

Macintyre. Circumstances, however, occurred which entirely changed his

prospects and pursuits. Soon after he had attained his fifteenth year,

his mother was married to Mr Thomas Smith, who had commenced life as a

tinsmith and lampmaker in Edinburgh, and who, being an ingenious

mechanician, afterwards directed his attention to the subject of

lighthouses. So successful were Mr Smith's endeavours to improve the

mode of illumination, by substituting oil lamps with parabolic mirrors

for the open coal-fires which formerly served for beacons to the

mariner, that his improvements attracted the notice of Professor Robison

and Sir David Hunter Blair, and he was appointed engineer to the

Northern Lighthouse Board, immediately after its constitution by the Act

of 1786. In these pursuits my father had rendered himself useful to Mr

Smith, who intrusted him, at the early age of nineteen, with the

superin-tendenoe of the erection of a lighthouse on the island of Little

Cumbrae in the river Clyde, according to a plan which Mr Smith had

furnished to the Trustees for the Clyde Navigation.' This connection

soon led to his adoption as Mr Smith's partner in business, and in 17.09

to his marriage with his eldest daughter; and as the entire management

of the lighthouse business had already for some years, with the

concurrence of the Board, devolved upon him, lie naturally succeeded Mr

Smith as engineer, an office which he resigned in 1843, after having

fulfilled its arduous duties for about half a century.

During the cessation of the works at Cumbrae in winter, Mr Stevenson,

who, even at that time, had determined to follow out the profession of a

civil engineer, and had begun to feel the want of systematic, training,

applied himself, it appears, with great zeal to the practice of

surveying and architectural drawing, and to the study of the

mathematical and physical sciences, at the Andersonian Institution at

Glasgow. Of the kindness of Dr Anderson, who presided over that

institution, he ever entertained a most grateful remembrance, and often

spoke of him as one of his best advisers and kindest friends. In the

manuscript memoranda already noticed, he thus records his obligations to

him. It was " the practice of Professor Anderson kindly to befriend and

forward the views of his pupils ; and his attention to me, during the

few years I had the pleasure of being known to him. was of a very marked

kind, for he directed my attention to various pursuits, with, the view

to my coming forward as an engineer."

After completing the Cumbrae Lighthouse, he was engaged under Mr Smith

in erecting lighthouses on the Pentland Skerries in Orkney, in returning

from whence, in 1794, he made a narrow escape from shipwreck in the

sloop Elizabeth of Stromness. The Elizabeth had proceeded as far as

Kinnaird Head on her southward voyage, and was then becalmed when within

about three miles of the shore. The captain kindly landed my father, who

continued his journey to Edinburgh by land. A very different fate,

however, awaited his unfortunate shipmates. A violent gale came on,

which drove the Elizabeth back to Orkney, where she was totally wrecked,

and all on board perished!

Notwithstanding his active duties in summer, he was so zealous in the

pursuit of knowledge that he contrived, during several successive

winters, on his return from Orkney, to attend the philosophical classes

at the University of Edinburgh. In this manner he attended Professor

Playfair's second and third mathematical courses, two sessions of

Professor Robison's natural philosophy, two courses of chemistry under

Mr Hope, and two of natural history under Professor Jameson. To these he

added a course of moral philosophy under Dugald Stewart, and also a

course of logic, and one of agriculture. "I was prevented, however," he

remarks, in the manuscript memoranda, "from taking my degree of M.A. by

my slender knowledge of Latin, in which my highest book was the Orations

of Cicero, and

by my total want of Greek." Such zeal in the pursuit of knowledge under

so many discouragements, and views so enlarged of the benefits and value

of a liberal education, were characteristics of a mind of no ordinary

vigour.

The most important work of Mr Stevenson's life is the Bell Rock

Lighthouse. Of the progress of that great undertaking he has left a

lasting memorial and most interesting narrative in his " Account," a

quarto volume of upwards of 500 pages, which was written to his

dictation by his only daughter. But there are some circumstances

connected with the early history of

that work which, while they could not properly have found a place in his

own narrative, have been noticed in the above-mentioned manuscript

memoranda, from which I shall transcribe a few paragraphs detailing his

early efforts and disappointments whilst designing that lighthouse:—

"All know the difficulties of the erection of the

Eddystone Lighthouse, and the casualties to which that edifice had been

liable; and in comparing the two situations, it was generally remarked

that the Eddystone was barely covered by the tide at high

water, while

the Bell Rock was barely uncovered at low

locder.

"I had much to contend with in the then limited state of

my experience; and I had in various ways to bear up against public

opinion as well as against interested parties. I was in this state of

things, however, greatly supported, and I would even say often

comforted, by Mr Clerk of Eldin, author of the System of Breaking the

Line in Naval Tactics. Mr Clerk took great interest in my models, and

spoke much of them in scientific circles—he carried men of science and

eminent strangers to the model-room which 1 had provided in Merchants'

Hall, of which he sometimes carried the key, both when I was at home and

while I was abroad. He introduced me to Lord Webb Seymour, to Admiral

Lord Duncan, and to Professors Robison and Playfair, and others. Mr

Clerk had been personally known to Smeaton, and used occasionally to

speak oi him to me."

It is impossible to read this little narrative without feeling a respect

for Mr Clerk's hearty enthusiasm, and perceiving the beneficial

influence which a kindly disposition, when thus united with an active

and inventive mind like his, is calculated to produce on the prospects

and pursuits of a young man, by stimulating an honourable emulation and

discouraging a desponding spirit.

"But at length," the memorandum continues, "all

difficulties with the public as well as with the better informed few,

were dispelled by the fatal effects of a dreadful storm from the X.E,

which occurred in December 1799, when it was ascertained that no fewer

than seventy sail of vessels were stranded or lost, with many of their

crews, upon the coast of Scotland alone ! Many of them, it was not

doubted, might have found a safe asylum in the Firth of Forth, had there

been a lighthouse upon the Bell Rock, on which, indeed, it was generally

believed the York, of 74 guns, with all hands, perished, none being left

to tell the tale! The coast for many miles exhibited portions of that

fine ship. There was now, therefore, but one voice,—'There must be a

lighthouse erected on the Bell Rock.'

Previous to this dreadful storm I had prepared my pillar

formed model, a section of which is shown in Plate VII. of the Account

of the. Bell Rock Lighthouse. Early

in the year 1800, I for the first time landed on the rock to see the

application of my model to the situation for which it was designed and

made. On this occasion I was accompanied by my friend Mr James Haldane,

architect, whose pupil I had been for architectural drawing. Our landing

was at low water of a spring-tide, when a good spare of

rock was above water, and then the realities of its danger were amply

exemplified by the numerous relics which were found in its crevices,

such as a ship's marking-iron, a piece of a kedge-anchor and a cabin

stove, a bayonet, cannon-ball, silver shoebuckle, crowbars, pieces of

money, and other evidences of recent shipwreck. I haft no sooner set

foot upon the rock than I laid aside all idea of a pillar-formed

structure, fully convinced that a building on similar principles with

the Eddystone would be found practicable.

"On my return from this visit to the rock, I immediately

set to work in good earnest with a design of a stone lighthouse, and

modelled it. Of this design a section is also given in Plate VII. above

noticed. I accompanied this design with a report or memorial to the

Lighthouse Board, which I gave in the Appendix of my 'Account' at p.

410. The pillar formed plan 1 estimated at £15,000, and the stone

building at £12,000.1 Put

still I found that I had not made much impression on the board on the

score of expense, for they feared it would cost much more than forty or

fifty thousand pounds. Here, therefore, the subject rested with the

Board for a time.

In order to fortify his views, he father requested the Board to take the

advice of Mr Telford, and ultimately of Mr Ronnie, who concurred with

him in thinking a stone tower practicable. But it appears that still the

banks would not advance money on the security, and the Board resolved to

apply for an Act of Parliament.

"To the very last the bankers were in doubt as to their

security on the dues for so great and hazardous an undertaking; and the

bill included an authority to borrow £25,000 from the Exchequer. I

attended this bill through Parliament. Mr Rennie and myself were

examined; but the only plans and information otherwise before the

Committee were those already noticed, which I had laid before the Board

in 1800.

"The Lighthouse Act having obtained the royal assent, I

began to feel a new responsibility. The erection of a lighthouse on a

rock about twelve miles from land, and so low in the water that the

foundation-course must be at least on a level with the lowest tide, was

an enterprise so full of uncertainty and hazard, that it could not fail

to press on my mind. I felt regret that I had not had the opportunity of

a greater range of practice to fit me for such an undertaking. But I was

fortified by an expression of my friend Mr Clerk, in one of our

conversations upon its difficulties. This

work,' said he, 'is unique, and can be little forwarded by experience of

ordinary masonic operations. In this case, Smeaton's Narrative must be

the text-book, and energy and perseverance the

pratique"

Mr Rennie, also, who had been appointed to advise with my father in case

of emergency, was not behind in administering comfort, and wrote to him,

during the progress of the work, in the following cheering terms: "Poor

old fellow" (alluding to the name of Smeaton), "I hope he will now and

then take a peep of us, and inspire you with fortitude and courage to

brave all difficulties and all dangers, to accomplish a work which will,

if successful, immortalise you in the annals of fame."

How well Mr Stevenson met the demands which, in the course of his great

enterprise, were made on his perseverance, fortitude, and self-denial,

the history of the operations, and their successful completion,

abundantly show. The work was, indeed, in all respects, peculiarly

suited to his tastes and habits; and Mr Clerk truly, although perhaps

unconsciously, characterised the man, in his terse statement of what

would be required of him. No one can read his account of the Bell Rock

Lighthouse without perceiving the justness of this estimate of his

character. His daily cheerful participation in all the toils and hazards

which were, for two seasons, endured in the floating light-ship, and

afterwards in the timber house or beacon, over which the waves broke

with prodigious force, and caused a most alarming twisting movement

of its main supports, were proofs not merely of calm and enduring

courage, but of great self-denial and enthusiastic devotion to his

calling. In one occasion in particular, his fortitude and presence of

mind were most severely tried, and well they stood the- test. I shall

give the narrative of this most interesting adventure in his own words;

but I cannot do so without expressing the regret I have so often felt,

that, from some mistaken delicacy, he had been induced throughout his

"Account" to speak of himself in the third person as "the writer." This

has encumbered the style with artificial phraseology, has damped the

ardour of the narrator, and in some instances has led to an awkward

ambiguity. The following passage possesses great interest:—

"Soon after the artificers landed they commenced work;

but the wind coming to blow hard, the Smeaton's boat and crew, who had

brought their complement of eight men to the rock, went off to examine

her riding-ropes, and see that they were in proper order. The boat had

no sooner reached the vessel than she went adrift, carrying the boat

along with her; and both had even got to a considerable distance before

this situation of things was observed, every one being so intent upon

his own particular duty that the boat had not been seen leaving the

rock. As it blew hard, the crew, with much difficulty, set the mainsail

upon the Smeaton, with a view to work her up to the buoy, and again lay

hold of the moorings. By the time that she was got round to make a tack

towards the rock, she had drifted at least three miles to leeward, with

the boat astern; and having both the wind and tide against her, the

writer perceived, with no little anxiety, that she could not possibly

return to the rock till long after its being overflowed ; for, owing to

the anomaly of the tides, formerly noticed, the Bell Rock is completely

under water before the ebb abates to the offing.

"In this perilous predicament, indeed, he found himself

placed between hope and despair ; but certainly the latter was by much

the most- predominant feeling of his mind,—situate upon a sunken rock,

in the middle of the ocean, which, in the progress of the flood-tide,

was to be laid under water to the depth of at least twelve feet in a

stormy sea. There were this morning in all thirty-two persons on the

rock, with only two boats, whose complement, even in good weather, did

not exceed twenty-four sitters ; but to row to the floating light with

so much wind, and in so heavy a sea, a complement of eight men for each

boat was as much as could with propriety be attempted, so that in this

way about one-half of our number was unprovided for. Under these

circumstances, had the writer ventured to despatch one of the boats, in

expectation of either working the Smeaton sooner up towards the rock, or

in hopes of getting her boat brought to our assistance, this must have

given an immediate alarm to the artificers, each of whom would have

insisted upon taking to his own boat, and leaving the eight artificers

belonging to the Smeaton to their chance. Of course, a scuffle might

have ensued, and it is hard to say, in the ardour of men contending for

life, where it might have ended. It has even been hinted to the writer

that a party of the pi'damn were

determined to keep exclusively to their own boat against all hazards.

"The unfortunate circumstance of the Smeaton and her boat

having drifted was, for a considerable time, only known to the writer,

and to the lamling-master, who removed to the further point of the rock,

where he kept his eye steadily upon the progress of the vessel. While

the artificers were at work, chiefly in sitting or kneeling postures,

excavating the rock, or boring with the junipers, and while their

numerous hammers, and the sound of the smith's anvil, continued, the.

situation of things did not appear so awful. In this state of suspense,

with almost certain destruction at hand, the water began to rise upon

those who were at work on the lower parts of the sites of the beacon

arid lighthouse. From the run of sea upon the rock, the forge fire was

also sooner extinguished this morning than usual, and the volumes of

smoke having ceased, objects in every direction became visible from all

parts of the rock. After having had about three hours' work, the men

began, pretty generally, to make towards their respective boats for

their jackets and stockings, when, to their astonishment, instead of

three they found only two boats, the third being adrift with the Smeaton.

Not a word was uttered by any one, but all appeared to be silently

calculating their numbers, and looking to each other with evident marks

of perplexity depicted in their countenances. The landing-master,

conceiving that blame might be attached to him for allowing the. boat to

leave the. rock, still kept at a distance. At this critical moment, the

author was standing upon an elevated part of Smith's Ledge, where he

endeavoured to mark the progress of the Smeaton, not a little surprised

that the crew did not cut the praam adrift, which greatly retarded her

way, and amazed that some, effort was not making to bring at least the

boat, and attempt our relief. The workmen looked stead fastly upon the

writer, and turned occasionally towards the vessel, still far to

leeward. All this passed in the most perfect silence, and the melancholy

solemnity of the, group made an impression never to be

effaced from his mind.

"The writer had ail along been considering various

schemes—providing the men could be kept under command—which might be put

in practice for the general safety, in hopes that the Smeaton might be

able to pick up the boats to leeward, when they were obliged to leave

the rock. He was, accordingly, about to address the artificers on the

perilous nature of their circumstances, and to propose that all hands

should unstrip their upper clothing when the higher parts of the rock

were laid under water; that the seamen should remove every unnecessary

weight and encumbrance from the boats; that a specified number of men

should go into each boat, and that the remainder should hang by the

gunwales, while the boats were to be rowed gently towards the Smeaton,

as the course to the Pharos or floating light lay rather to windward of

the rock. Put when he attempted to speak, his mouth was so parched that

his tongue refused utterance, and he now learned by experience that the

saliva is as necessary as the tongue itself for speech. He then turned

to one of the pools on the rock and lapped a little water, which

produced an immediate relief. But what was his happiness when, on rising

from this unpleasant beverage, some one called out 'a boat! a boat!' and

on looking around, at no great distance, a large boat was seen through

the haze making towards the rock. This at once enlivened and rejoiced

every heart. The timeous visitor proved to be James Spink, the Bell Bock

pilot, who had come express from Arbroath with letters. Spink had for

some time seen the Smeaton, and had even supposed, from the state, of

the weather, that all hands were on board of her, till ho approached

more nearly and observed people upon the rock. Upon this fortunate

change of circumstances sixteen of the artificers were sent at two trips

in one of the boats, with instructions for Spink to proceed with them to

the floating light. This

being accomplished, the remaining sixteen followed in the two boats

belonging to the service of the rock. Every one felt the most perfect

happiness at leaving the Bell Rock this morning, though a very hard and

even dangerous passage to the floating light still awaited us, as the

wind by this time had increased to a pretty hard gale, accompanied with

a considerable swell of sea. The boats left the rock about nine, but did

not reach the vessel till twelve o'clock noon, after a most disagreeable

and fatiguing passage of three hours. Every one was as completely

drenched in water as if he had been dragged astern of the boats."

The state of suffering and discomfort as well as danger on board the

floating light, which lay moored off the rock during the first two

seasons of the work, before the timber Beacon was used as a habitation,

is described in the following passage, which presents a striking

illustration of the continual anxiety that must have existed in the

minds of those engaged in the work, and of the frequent calls for

energetic and courageous exertion.

"About two o'clock p.m.

a great alarm was given throughout the ship, from the effects of a very

heavy sea which struck her, and almost filled the waist, pouring down

into the berths below, through every cliink and crevice of the hatches

and skylights. From the motion of the vessel being thus suddenly

deadened or checked, and from the flowing in of the water above, it is

believed there was not an individual on board who did not think, at the

moment, that the vessel had foundered and was in the act of sinking. The

writer could withstand this no longer, and as soon as she again began to

range to the sea, he determined to make another effort to get upon deck.

"It being impossible to open any of the hatches in the

fore part of the ship in communicating with the deck, the watch was

changed by passing through the several berths to the companion-stair

leading to the quarter-deck. The writer, therefore, made the best of his

way aft, and on a second attempt to look out, ho succeeded, and saw

indeed an astonishing sight. The seas or waves appeared to be ten or

fifteen feet in height of unbroken water, and every approaching billow

seemed as if it would overwhelm our vessel, but she continued to rise

upon the waves, and to fall between the seas in a very wonderful manner.

It seemed to be only those, seas which caught her in the act of rising

which struck her with so much violence, and threw such quantities of

water aft. On deck there was only one solitary individual looking out,

to give the alarm in the event of the ship breaking from her moorings.

The seaman on watch continued only two hours ; he had no greatcoat nor

overall of any kind, but was simply dressed in his ordinary jacket and

trousers; his hat was tied under his chin with a napkin, and he stood

aft the foremast, to which he had lashed himself with a gasket or small

rope round his waist, to prevent his falling upon deck or being washed

overboard. Upon deck everything that was moveable was out of sight,

having either been stowed below previous to the gale, or been washed

overboard Some trifling parts of the quarter-boards were damaged by the

breach of the sea, and one of the boats upon deck was about one third

full of water, the oyle-hole or drain having been accidentally stopped

up, and part of the gionwale had received considerable injury. Although

the previous night had been a very restless one, it had not the effect

of inducing sleep in the writer's berth on the succeeding one; for

having been so much tossed about in bed during the last thirty hours, he

f< wild no easy spot to turn to, and his body was all sore to the touch,

which ill accorded with the unyielding materials with which his bed

place was surrounded.

"This morning about eight o'clock the writer was

agreeably surprised to see the scuttle of his cabin skylight removed,

and the bright rays of the sun admitted. Although the ship continued to

roll excessively and the sea was still running very high, yet the

ordinary business on board seemed to be going forward on deck. It was

impossible, to steady a telescope so as to look minutely at the progress

of the waves, and trace their brcach upon the Bell Bock, but the height

to which the cross-running waves rose in sprays, when they met each

other, was truly grand, and the continued roar and noise of the sea was

very perceptible to tho ear. To estimate the height of the sprays at 40

or 50 feet would surely be within the mark. Those of the workmen who

were not much afflicted with sea-sickness came upon deck, and the

wetness below being dried up, the cabins were again brought into a

habitable state. Every one seemed to meet as if after a long absence,

congratulating his neighbour upon the return of good weather, little

could be said as to the comfort of the vessel; but after riding out such

a gale, no one felt the least doubt or hesitation as to the safety and

good condition of her moorings. The master and mate were extremely

anxious, however, to heave in the hempen cable, and see the state of the

clinch or iron ring of the chain cable. But the vessel rolled at such a

rate that the seamen could not possibly keep their feet at the windlass,

nor work the handspokes, though it had been several times attempted

since the gale took off.

'"About twelve noon, however, the vessel's motion was

observed to be considerably less, and the sailors were enabled to walk

upon deck with some degree of freedom. But to the astonishment of every

one it was soon discovered that the floating light was adrift! The

windlass was instantly manned, and the men soon gave out that there was

no strain upon the cable. The mizzen sail, which was bent for the

occasional purpose of making the vessel ride more easily to the tide,

was immediately set, and the other sails were also hoisted in a short

time, when, in no small consternation, we bore away about one mile to

the south-westward of the former station, and there let go the best

bower-anchor and cable, in twenty fathoms water, to ride until the swell

of the sea should foil, when it might be practicable to grapple for the

moorings, and find a better anchorage for the ship.

" As soon as the deck could be cleared the cable-end was

hove up, which had parted at the distance of about 50 fathoms from the

chain moorings. On examining the cable, it wan found to be considerably

chafed, but where the separation took place, it appeared to be worn

through, or cut shortly off. How to account for this would be difficult,

as the ground, though rough and gravelly, did not, after much sounding,

appear to contain any irregular parts. It was therefore conjectured that

the cable must have hooked some piece of wreck, as it tlid not appear

from the state of the wind and tide that the vessel could have fouled her

anchor when she veered round with the wind, which had shifted in the

course of the night from N. E. to N.N.W.

"Be this as it may, it was a circumstance quite out of

the power of man to prevent, as, until the ship drifted, it was found

impossible to heave up the cable. But what ought to have been the

feeling of thankfulness to that Providence which regulates and appoints

the lot of man, when it is considered that if this accident had happened

during the storm, or in the night after the wind had shifted, the

floating light must inevitably have gone ashore upon the Bell Rock. In

short, it is hardly possible to conceive any case more awfully

distressing than our situation would have been, or one more disastrous

to the important undertaking in which we were engaged."

The Beacon or Barrack, which was afterwards erected on the rock as a

substitute for the floating li-lit, was inhabited by Mr Stevenson and

twenty-eight men. It was a singular habitation, somewhat resembling a

pigeon-house, perched on logs, on which the tide rose sixteen feet in

calm weather, and was exposed to the assault of every wave. Of the

perils and discomforts of such a habitation, the following passages give

a lively picture :—

"This scene" (the sublime appearance of the waves) "he

greatly enjoyed while sitting at his window. Each wave approached the

Beacon like a vast scroll unfolding, and in passing discharged a

quantity of air which he not only distinctly felt, but was even

sufficient to lift the leaves of a book which lay before him.....

"The gale continues with unabated violence to-day, and

the sprays rise to a still greater height, having been carried over the

masonry of the building, or about 90 feet above the level of the sea. At

four o'clock this morning it was breaking into the cook's berth (on the

Beacon), when he rang the alarm-bell, and all hands turned out to attend

to their personal safety. The floor of the smith's or mortar gallery was

now completely burst up by the force of the sea, when the whole of the

deals and the remaining articles upon the floor were swept away, such as

the cast-iron mortar-tubs, the iron hearth of the forge, tho smith's

bellows, and even his anvil, were thrown down upon the rock. The

boarding of the cook house, or storey above the smith's gallery, was

also partly carried away, ami the brick and plaster work of the

fireplace shaken and loosened. It was observed during this gale that the

beacon- house had a good deal of tremor, but none of that 'twisting

motion,' occasionally felt and complained of before the additional

wooden struts were set up for the security of the principal beams; hut

this effect hail more especially disappeared ever since the attachment

of the great horizontal iron bars in connection with these supports,

instead of the chain-braces shown in Plate Till. Before the tide rose to

its full height to-day, some of the artificers passed along the bridge

into the lighthouse, to observe the effects of the sea upon it, and they

reported that they had felt a slight tremulous motion in the building

when great seas struck it in a certain direction about high-water mark.

On this occasion the sprays were again observed to wet the balcony, and

even to come over the parapet 'Wall into

the interior of the light-room. In this state of the weather, Captain

Wilson and the crew of the ' Floating Light' wore much alarmed for the

safety of the artificers upon the rock, especially when they observed

with a telescope that the floor of the smith's gallery had been carried

away, and that the triangular cast-iron sheer-crane was broken down. It

was quite impossible, however, to do anything for their relief until the

gale should take off.

"The writer's cabin measured not more than 4 feet 3

inches in breadth on the floor : and though, from the oblique direction

of the beams of the Beacon it widened towards the top, yet it did not

admit of the full extension of his arms when he stood on the floor;

while its length was little more than sufficient for suspending a

cot-bed during the night, calculated for being triced tip to the roof

during the day, which left free room for the admission of occasional

visitants. His folding-table was attached with hinges immediately under

the. small window of the apartment; and his books, barometer,

thermometer, portmanteau, and two or three camp-stools, formed the bulk

of his movables. His diet being plain, the paraphernalia of the table

were proportionately simple ; though everything had the appearance of

comfort and even of neatness, the walls being covered with green cloth,

formed into panels with red tape, and his bed festooned with curtains of

yellow cotton stuff. If, on speculating on the abstract wants of man in

such a state of exclusion, one were reduced to a single book, the sacred

volume, whether considered for the striking diversity of its story, the

morality of its doctrine, or the important truths of its Gospel, would

have proved by far the greatest treasure."

The great merit due to Mr Stevenson, as the architect of the Bell Rock

Lighthouse, lies in his bold conception of, and confident unshaken

belief in, the possibility of executing a tower of masonry on the Bell

Hock, which being left dry only at very low tides, and covered at high

water to the depth of sixteen feet, obviously presented much greater

difficulty than the Eddystone. But his mechanical skill in carrying on

the work is also deserving of high praise. Not only did he conceive the

plan of the jib and balance

cranes—which

he applied, with much advantage, in the erection of the tower—but his

zeal, ever alive to the possibility of improving on the conceptions of

his great master, Smeaton, led him to introduce some very advantageous

changes in the arrangements of the masonry of the tower ; and, in

particular, as described below, he converted the floors of the

apartments into conservative ties, while in the Eddystone they exert an

outward thrust, which the architect counteracted by metallic chains

imbedded in a groove tilled with molten lead.

"The floor-courses of the Bell Bock Lighthouse lay

horizontally upon the walls, as will be seen the sections in Hates VII.

and XVI. They consisted in all of eighteen blocks, but only sixteen were

laid in the first instance, as the centre stones were necessarily left

out, to allow the shaft of the balance-crane to pass through the several

apartments of the building. In the same manner also the stone which

formed the interior side of the man-hole was not laid till after the

centre stone was in its place and the masonry of the walls completed.

The number of stones above alluded to are independently of the sixteen

joggle pieces with which the principal blocks of the floors were

connected, as shown in the diagrams of Plates VII. and XIII. The floors

of the Eddystone Lighthouse, on the contrary, were constructed of an

arch form, and the haunches of the arches bound with chains, to prevent

their pressing outward to the injury of the walls. In this, Mr Smeaton

followed the construction of the dome of St Paul's; and this mode might

also be found necessary at the Eddystone, from the want of stones in one

length to form the outward wall and floor, in the, then state of the

granite quarries of Cornwall At Mylnetield quarry, however, there was no

difficulty in procuring stones of the requisite dimensions; and the

writer foresaw many advantages that would arise from having the stones

of the floors to form part of the outward walls without introducing the

system of arching. In particular, the pressure of the floors upon the

walls would thus be perpendicular ; for as the stones were prepared in

the sides with groove

and feather, after

the manner of the common house-floor, they would, by this means, form so

many girths, binding the exterior walls together, as will be understood

by examining the diagrams and section of Plate VII., with its

letterpress description; agreeably to which, he had modelled the floors

in his original designs for the Bell Rock, which were laid before the

Lighthouse Board in the year 1800."

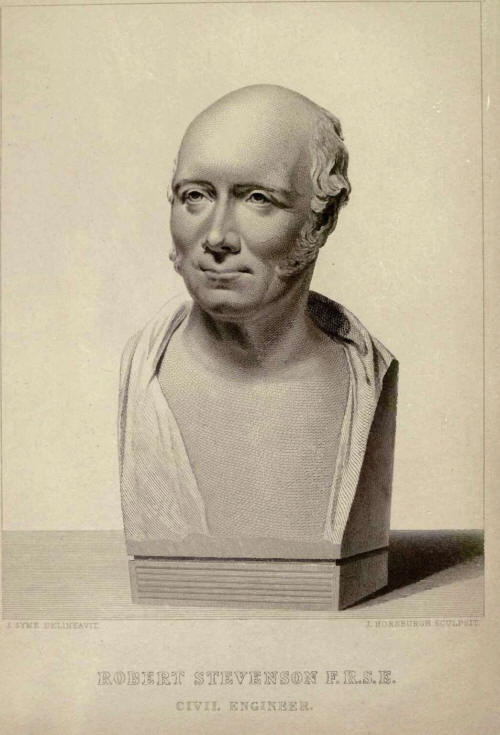

The Commissioners entertained a high sense of my father s services at

the Bell Rock Lighthouse; and as many of them took a deep interest in

the whole of that remarkable work, and paid occasional visits to it

during its progress, they were well able to appreciate the ability and

zeal with which he devoted himself to this arduous task. It was moved by

the late Sir William Rao, Baronet, then Lord Advocate of Scotland, at a

meeting held in the lighthouse itself on the 19th .July 1824—"That a

bust of Mr Robert Stevenson be obtained and placed iu the library of the

Bell Rock Lighthouse, in testimony of the sense entertained by the

Commissioners of his distinguished talent and indefatigable zeal in the

erection of that lighthouse." A beautiful bust, in marble, by Samuel

Joseph, from which the plate prefixed to this memoir was taken, was

accordingly placed in the library of the lighthouse. From its striking

resemblance, it recalls in a very pleasing manner the memory of my

father, coupled with many of bis counsels delivered on the spot during my

frequent visits to the Bell Bock in his company.

It appears, from the minutes of the Commissioners, that my father

performed his first tour of inspection of the lighthouses, and made the

Annual Report to the Board, in the year 1707. During the long period of

his incumbency which followed, he designed and executed twenty-three

lighthouses in the district of the Commission, many of them in

situations which called for much forethought and great energy. All his

works were characterised by the same sagacity and comprehensive views,

and exhibit successive stages of improvement, equally indicative of the

growing prosperity of the Board, and the alacrity and zeal with which

their engineer laboured in his vocation. In no country has the Catoptric system

of illuminating lighthouses been brought to so high a degree of

perfection as in Scotland; and in consequence of information which he

received from Colonel Colby, of the invention of the Dioptric light

by Fresnel, my father was the first to bring the merits of that system

before the Commissioners of Northern Lighthouses, in his

Report

of December 1821. Whether we consider the accuracy and beauty of the

optical apparatus, the arrangements of the buildings, or the discipline

observed by the light-keepers of the Northern Lighthouses, we cannot

fail to recognise the impress of that energetic and comprehensive cast

of mind which directed the whole. With the strictest propriety my father

may be said to have created and perfected the lighthouse system of

Scotland. His merits indeed, in this respect, were generally

acknowledged in other quarters; and many of the Irish lighthouses, and

several lighthouses in our colonies, were fitted up with apparatus

prepared under his superintendence. "While writing on this subject, I

can hardly omit to quote the ©pinion of the Astronomer-Royal, formed

after having inspected lighthouses, both in this country and in France.

Mr Airev says, in his Report to the Royal Commission on Lighthouses,

dated October 10, 1860:—"This lighthouse (Girdleness, in Aberdeenshire)

contains two systems of lights. The lower, at about two-fifths the

height of the building, consists of thirteen parabolic reflectors, of

the usual form. I remarked in these that, by a simple construction which

I have not seen elsewhere, great facility is given for the withdrawal

and safe return of the lamps, for adjusting the lamps, and cleaning the

mirrors;" and, in closing his Report, he adds, "It is the best

lighthouse that I have seen." In the course of his labours as engineer

to the Lighthouse Board, my father's attention was much given to the

subject of distinction anion-lights, a matter of the utmost importance

in narrow seas, where many lights are required. He was the inventor of

two useful distinctions—the intermittent and Flashing lights,

for the latter of which he received from the late King of the

Netherlands a gold medal, as a mark of his Majesty's approbation. In the

first of those distinctions the light is suddenly obscured and as

suddenly revealed to sight, at unequal intervals of time, in a manner

which completely distinguishes it from the ordinary revolving light,

which from darkness gradually increases

in power till it reaches its brightest phase, and then gradually

declines until it is again obscured. The flashing light exhibits, by

means of a rapid revolution of the frame which carries the lamps, and a

peculiar arrangement in their position, a sudden flash of great power,

once in five seconds of time.

Besides his official duties as engineer to the Lighthouse Board, he took

a large share in the general engineering of his day, and acted on many

occasions in conjunction with Bennie, Nimmo, Telford, and afterwards

with Walker and Cubitt, with all of whom he ever maintained a friendly

intercourse. Soon after the peace in 1815 the public mind was naturally

directed to the improvement of our internal resources, which the long

continuance of the Continental war had thrown unduly into the shade.

Roads, bridges, harbours, canals, and railways, soon became topics of

public attention and general interest; and my father's known sagacity

and energy rendered him a useful adviser on many of those subjects. In

the course of his professional life he designed and executed several

important bridges, such as those of Stirling, Marykirk, Annan, and the

Hutcheson Bridge over the Clyde at Glasgow^. Of the latter. Mr Fenwick,

of the Royal Military Academy, Woolwich, in the preface to his work on

the Mechanics

of Construction, published

in 1861, says:—"The London and Waterloo bridges in the metropolis, which

rank among tho finest structures of the elliptical

arch, and

Stevenson's Hutcheson Bridge at Glasgow, which is one of the best

specimens of the segmental

arch,

together with many others, have supplied me with a variety of problems

for illustration." In 1826 he gave a design to the corporation of

Newcastle for raising on the existing bridge another roadway, on a high

level, to communicate with the higher parts of the town ; being the very

idea since so successfully carried out by the late Mr Robert Stephenson

in his justly celebrated " high-level railway viaduct."

The beautiful approaches to the City of Edinburgh from the east, by the

Calton Hill, known as the London and Regent Roads, were designed by my

father, and executed under his direction; and 1 mention this the more

willingly, as it seems difficult to conceive anything finer than the

splendid entrance by the High School and Jail, to what Sir Walter Scott

has called "our own romantic town."'3 He

also surveyed and traced the lines of many canals and railways, which

have since been executed, more or less, in accordance with the advice

contained in his numerous printed reports. We may especially mention his

projected canal, and afterwards railway, on

one level, between

Edinburgh and Glasgow; his great Strathmore Canal and Railway, on one

level, which would have connected the towns of Perth, Forfar, Arbroath,

Montrose, and Brechiu, and his railway from Stockton to Darlington. In

1818 the Highland Society of Scotland offered a premium of fifty guineas

for the best essay on the construction of railroads. Many competing

treatises were given in, and the Society placed the whole of them in the

hands of my father for his opinion and report on their merits, "together

with such remarks of his own as he might judge useful.'" The result of

his examination is given at great length in the Transactions of the

Society,4 accompanied

by "notes," in which he makes several valuable suggestions. Before the

period alluded to, the rails in use had been almost invariably made of

cast-iron or timber; but my father, in his notes, says,—"I have no

hesitation in giving a decided preference to malleable iron, formed into

bars from twelve to twenty feet in length, with flat sides and parallel

edges, or in

the simple state in which they come from the rolling mills of the

manifacturer." He

also recommends that they should be fixed into guides or chairs of iron,

supported on props placed at distances in no case exceeding three feet,

and that they should he connected with a clamp-joint, so as to preserve

the whole strength of the material. It is not a little singular that

this description, given about forty years ago, may, to use engineering

phraseology, be not inaptly called a "specification of the permanent

way" of our best railways at the present day. The following letter,

written in 1821, shows the value which Mr George Stephenson, who has

been justly styled the pioneer of railway engineers, attached to my

father's suggestions, while it is, at the same time, interesting, as

showing the very moderate estimate which the great railway engineer then

cutertained of the performance of the locomotive engine—a machine which

was destined afterwards in his hands to become so important in changing

the inland communication of the whole civilised world :—

Killingworth Colliery, June 28,

1821.

R obERt

Stevenson, Esq.

Sir.—With

this you will receive 3 copies

of a specification of a patent malleable-iron rail invented by John

Kirkinshaw of Bedlington, near Morpeth. The hints were got from your

Report on Railways, which you were so kind as to send me by favour of Mr

Cookson some, time ago. Your reference to Tindale-fell Railway led the

inventor to make some experiments on malleable-iron bars, the result of

which convinced him of the superiority of the malleable over the cast

iron—so much so, that he took out a patent. Those rails are so much

liked in this neighbourhood, that I think in a short time they w ill do

away the cast-iron railways. They make a fine line for our engines, as

there are so few-joints compared with the other. I have lately started a

new locomotive engine, with come improvements on the others which you

saw: it Las far surpassed my expectations. I am confident a railway on

which my engines can work is far superior to a canal. On

a long and favourable, railway I would stent my engines to travel 00

miles per day with from 40 to 80 tons of goods. They would work nearly

fourfold cheaper than horses where coals are not very costly. I merely

make these observations, as I know you have been at more trouble than

any man I know of in searching into the utility of railways; and I

return you my sincere thanks for your favour by Mr Cookson.

If you should be in this neighbourhood, I hope you would

not pass Killingworth Colliery, as I should be extremely glad if you

could spend a day or two with me.—I am, sir, yours most respectfully,

(Signed) G. Stephenson.

In the same notes my father also suggests a new form of stone tracks

used for easing the draught on common roads. Specimens of it were laid

down under his direction on the South Bridge and Pleasance, and a sample

of it may he seen at Liberton hill, near Edinburgh. Within the last few

years it has been proposed to lay such stone tracks on several of the

turnpike roads throughout the country.

In 1825 he proposed a form of suspension bridge, applicable to small

spans, in which the roadway passes above the

chains, and the necessity for tall piers is avoided. The Suspension

Bridge, over the Ilhone at Geneva, and other bridges, have been

constructed on this principle. For timber bridges he also proposed a new

form of arch of a beautiful and simple construction, in which what might

be called the ring-courses of the arch are formed of layers of thin

planks bent into the circular form and stiffened by king-pod

pieces, on

which the level roadway rests. This form of bridge has since come into

very general use on railways. His proposal to adopt the cycloidal curve

for the vertical profiles of seawalls, which he carried into execution

at Trinity, near Edinburgh, and his design for securing constant

motion, by

causing the hydrostatic pressure of the varying level of the tide to

toll a bell, as a warning signal for the Carr Rock Beacon, are further

instances of the inventive turn of his mind.

There is scarcely a harbour or a navigation in Scotland about which at

some time he did not give valuable advice; and he was also often

consulted in England and Ireland—on the Severn, Mersey, Dee, Wear, Tees,

Erne, and other rivers and harbours. His published reports and

contributions to engineering knowledge extend, when collected, to four

thick quarto volumes ; and during his long life of industry he did much

which, like a large portion of the labours of all professional men, was

never known beyond the sphere immediately affected by it.

In addition to his professional exertions, he took an active part in

advancing the interests of science in so far as lay in his power, and

was one of the original promoters of the Astronomical Institution, out

of which has grown the present establishment of the Royal Observatory.

In 1815 he became a Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh; and he

afterwards joined the Geological Society of London, and the Wernerian

and Antiquarian Societies of Scotland. In 1816 he published his memoir

on the alveus or bed of the German Ocean, in which he showed, by an

appeal to many evidences, that the sea was gradually encroaching on the

land, and that the sand-banks in the German Ocean are the result (if the

degradation of the adjoining shores. In this memoir, which has been

quoted by Lyell, Cuvier, and others, he estimates the sand-banks in the

German Ocean as equal to the cubic contents of a stratum of that sea

fourteen feet in thickness. In the year 1812, while engaged on the Pee

at Aberdeen, in making certain observations under a remit from the Court

of Session, he discovered the interesting fact, which has since become

so well known, that the salt water of the ocean flows lip the beds of

rivers in a stream quite distinct from the outflowing fresh water,

which, owing to its smaller specific gravity, floats on the surface. In

order to test the truth of his hypothesis, he had an instrument hastily

fitted up by an optician in Aberdeen, by which he found that while the

water on the surface was fresh, that raised from the bottom was

perfectly salt. This instrument, now termed a hydrophore, is often

employed in engineering and scientific inquiries for drawing specimens

of water from different depths in rivers and estuaries. He also made

several contributions to the Encyclopaedia

Britannica, to

the Edinburgh

Encyclopaedia, and

to various scientific journals of the day; and gave (in a series of

Letters which appeared in the

Scots Magazine in

1817, a lively and instructive account of a tour through the

Netherlands, in which he described some of the most interesting

engineering works connected with the drainage and embankment of Holland.

Sagacity, fortitude, and perseverance were very prominent points of Mr

Stevenson's character. In private life he was a man of sterling worth ;

and whether we regard him as a husband, a father, or a friend, he was

equally distinguished by the absence of selfishness and by his great

generosity. His exertions in forwarding the progress of young men

through life were extensive and unwearied ; and few men had more solid

grounds than he for indulging in the pleasing reflection that, both in

his public and private capacity, he had consecrated to beneficial ends

every talent committed to his trust. Many of his personal friends have

recorded the pleasant satisfaction with which they continued through

life to look back upon the days spent in Mr Stevenson's company on board

the lighthouse tender, on the occasion of his making his annual

inspection of the lighthouses. On one of those voyages made in 1814 he

was accompanied by Sir Walter Scott, who has given a graphic description

of it in his autobiography, from which I shall quote a single passage,

giving an amusing account of the first landing made by the Commissioners

on the rock on which the Skerryvore lighthouse has since been erected.

"Having crept upon deck about four in the morning," says

Sir Walter, "I find we are beating to windward off the Isle of Tyree,

with the determination, on the part of Mr Stevenson, that his

constituents should visit a reef of rocks called Skerry Vhor, where he

thought it would be essential to have a lighthouse. Loud remonstrances

on the part of the Commissioners, who, one and all, declare they will

subscribe to his opinion, whatever it may he, rather than continue the

infernal buffeting. Quiet perseverance on the part of Mr S., and great

kicking, bouncing, and squabbling upon that of the yacht, who seems to

like the idea of Skerry Vhor as little as the Commissioners. At length,

by dint of exertion, come in sight of this long ride of rocks (chiefly

under water), on which the tide breaks in a most tremendous style. There

appear a few low broad rocks at one end of the reef, which is about a

mile in length. These are never entirely under water, though the surf

dashes over them. To go through all the forms, Hamilton, Duff, and I

resolve to land upon these bare rocks in company with Mr Stevenson. Pull

through a very heavy swell with great difficulty, and approach a

tremendous surf dashing over black, pointed rocks. Our rowers, however,

get the boat into a quiet creek between two rocks, where we contrive to

land well wetted. I saw nothing remarkable in my way excepting several

seals, which we might have shot, but, in the doubtful circumstances of

the landing, we did not care to bring guns. We took possession of the

rock in name of the Commissioners, and generously bestowed our own great

names on its crags and creeks. The rock was carefully measured by Mr S.

It will be a most desolate position for a lighthouse, the Bell Rock and

Eddy stone a joke to it, for the nearest land is the wild island of

Tyree, at fourteen miles distance. So much for the Skerry Vhor."

On landing at the Bell Rock Lighthouse, the great poet inscribed in the

Album some lines which will be found in the vignette of the lighthouse

prefixed to this memoir.

My father was a man of sincere and unobtrusive piety; and although

warmly attached to the Established Church of Scotland, of which for

nearly forty years he had been an elder, he had no taint of bigotry or

of party feeling. A high sense of duty pervaded his whole life; and he

died calmly in that blessed hope and peace which only an indwelling and

personal belief in the merits of a Redeemer can impart to any son of our

guilty race.

At a Statutory General Meeting of the Board of Northern Lighthouses,

which was held on the 13th July 1850, the day after his death, the

Commissioners recorded their respect for his talents and virtues in the

following Minute :—

"The Secretary having intimated that Mr Robert Stevenson,

the late Engineer to the Board, died yesterday morning,

"The Board, before proceeding to business, desire to

record their regret at the death of this zealous, faithful, and able

officer, to whom is due the honour of conceiving and executing the great

work of the Bell

Rock

Lighthouse, whose services were gratefully acknowledged on his

retirement from active duty, and will be long remembered by the Board;

and to express their sympathy with his family on the loss of one who was

most estimable and exemplary in all the relations of social and domestic

life. The Board direct that a copy of this resolution be transmitted to

Mr Stevenson's family, and communicated to each Commissioner, to the

different light-keepers, and the other officers of the Board."

A. S,

August 8,

1861 |

|