|

TOWARD the close of the

war, even before peace had been actually declared, the country began

slowly to shake off the lethargy from which it had not recovered

altogether since the panic of 1857. Industry revived, the current of

trade began to move again, and a period of development, which was to

endure for several years, was soon under way. The effect of the

revival upon the lumber industry was most pronounced. The average

price, which had been only twelve dollars a thousand up to 1863,

reached twenty-four dollars before the end of the following year.

The change marked the

beginning of a tremendous development of the Menominee River region,

the production of which was to mount upward within less than a score

of years from one hundred million to approximately seven hundred

million feet. More mills were erected, older mills were enlarged,

and on the lower reaches of the river and along the bay shore the

lumber area steadily expanded. Operations in the forests above were

extended with proportionate rapidity. This necessitated the creation

of a central organization to handle the enormous number of logs

driven down the stream and distribute them among the numerous

manufacturing plants and resulted in the incorporation of the

Menominee River Manufacturing Company, afterward called the

Menominee River Boom Company.

In 1865 I had built

piers in the river to facilitate the handling of timber, but these

proved to be inadequate for the growing requirements and during the

following year a freshet swept. several million feet of logs out

into the bay. This awakened the mill owners to the necessity of

concerted action, and the establishment of the boom, which had for

its prototype the Oldtown boom on the Penobscot, constructed and

managed by Jefferson Sinclair, followed soon after.

This placed

additional responsibilities upon my shoulders. There was no one else

among the mill owners who had had practical experience in this kind

of work, in which I had learned many valuable lessons from Mr.

Sinclair and the lumbermen of Maine, and I was accordingly made

president of the concern, an office which I still hold, and given

full direction of its affairs. It was no small task. To secure the

necessary flow of water and regulate the swift current of the river,

forty damns were built on the main stream and its tributaries, some

of which supply power for traction, lighting, and manufacturing

to-day. These were of the gravity type with a broad sloping base. In

constructing them we were without the advice of engineers and the

advantages of modern mechanical contrivances and materials, but they

have stood the test of a half-century. On the Peshtigo River I built

twenty-seven more damns, making sixty-seven in all - a record in

which I take some pride.

The Menominee River

Boom Company is no longer the important institution it was in the

halcyon days of lumbering. The millions of feet of pine and hemlock

logs, which sometimes extended from bank to bank for miles along the

stream, have dwindled to less than one-tenth of the original number,

as the forests have been stripped and the huge straight trunks free

of limbs have given way to small knotted timber, but the system

remains the same.

These were days of

large industrial enterprise and men of great capacity and breadth of

view were required to encompass and make the most of the

opportunities that began to appear upon the brightening horizon. And

such men were forthcoming. Some of them, it seems, were endowed with

almost prophetic vision and yet were sufficiently trained in the

school of experience to progress with safe and sure steps toward the

attainment of the dimly discernible ideals that have since been

realized. Many of these men it was my good fortune, by reason of the

position I held, to be associated with and to know.

Towering above all of

them physically as well as mentally, in energy, breadth of vision,

and masterful enterprise, was William B. Ogden, the first mayor of

Chicago. For ten years I was closely associated with him in business

and saw much of him at his home in Chicago and later on in New York.

During that time I had ample time to judge of him in an environment

of business men. To my mind he was one of the dominating figures of

the Middle West during this period and had as much if not more to do

with its development than any other man.

He was moderate,

almost abstemious, in his habits. He worked eighteen hours out of

the twenty-four, planning his schemes of constructive enterprise and

reviewing matters submitted to him for final decision. Only a small

part of the undertakings he had projected were carried out, but even

these gave him place as a man of very large business affairs. He was

one of the pioneers who built the railroad from Galena to Chicago.

He also built the Northwestern Railroad from Chicago to Green Bay

and was president of and a large stockholder in the company. In

Chicago and elsewhere his enterprises were almost without number,

and his activities as agent of wealthy capitalists in the United

States and abroad covered a. wide field.

When the panic of

1857 came, Mr. Ogden had outstanding paper to the amount of

$1,500,000, a much larger sum according to the scale of operations

at that time than it appears measured by present standards. When he

went to New York to arrange matters to tide himself over the crisis

he engaged Samuel J. Tilden as his attorney. Subsequently the two

men became very fast friends and Tilden was made a director in the

Northwestern Railroad Company. In such esteem was Mr. Ogden held in

Chicago that upon his return from this trip he was greeted by

bonfires all over the city.

In the fires of 1871,

at Chicago and Peshtigo, he lost upward of five million dollars,

possibly twice or thrice that sum. When the disaster overtook him

two of his clients, one a wealthy man in New York, another in

England, wrote to his brother, Mahlon Ogden, who was in charge of

his real estate operations, directing him to sell out their holdings

and devote the proceeds to the liquidation of Mr. Ogden's debts. By,

this display of friendship Mr. Ogden was deeply touched, and from

that time until his death in 1878 the portraits of his two

benefactors, who, as it happened, were not called upon to make the

sacrifice they proposed, hung in his house. Despite the losses he

suffered, he left a large estate.

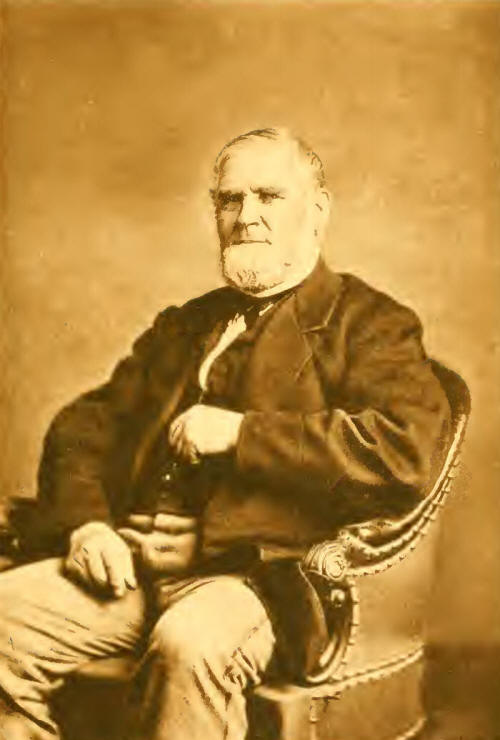

William B. Ogden

Iii the autumn of

1864 Mr. Ogden and Mr. Tilden, who were returning from an inspection

of their mines in the Lake Superior copper district, stopped at

Marinette on their way to Chicago and were my guests for thirty-six

hours, The national campaign was then in full swing. Both Mr. Ogden

and Mr. Tilden were of the Democratic faith, although they were in

favor of the preservation of the Union and upheld the principle of

protection, and had before leaving Chicago played a conspicuous part

in the nomination of George B. McLellan on the Democratic ticket.

They told me at the time that the platform upon which McLellan ran

was prepared in Mr. Ogden's library. It was the best, Mr. Tilden

said, that Vallandigham's wing of the party, the "copperheads,"

would accept. I gave Mr. Tilden a copy of the Green Bay Advocate

containing a copy of McLellan's letter of acceptance, and after

reading it he observed that McLellan had added the soldiers' plank

in accordance with a suggestion he had made to him to "tune it up

some."

A few years later I

had occasion to go to New York several times on business matters,

and on one of these visits, while stopping with Mr. Ogden at his

home, an imposing residence on the Harlem River just above the

aqueduct bridge, made the suggestion that, Tilden, who had then been

been governor of New York, was the strongest candidate the Democrats

could select for President. The same idea must have been lurking in

Mr. Ogden's mind, although I had never heard it expressed before,

for, when I made the remark, his face brightened.

"Stephenson," he said

eagerly ''will you support him?"

"Oh, no!" I replied.

"I am a Republican."

In 1870 Tilden was

nominated and, it is very generally admitted, was elected, although

counted out. From patriotic motives, it was said at the time, he

preferred to make no contest rather than stir up serious trouble.

From Marinette Mr.

Ogden and Mr. Tilden went to Peshtigo, where the former had a large

lumbering establishment. Using this as a nucleus it was his purpose

to erect a large plant for the manufacture of woodenware and other

products, but he encountered serious difficulty in the lack of a

manager in whom he had confidence to take charge of these

operations. For four years, since I had first met him in 1863, he

had tried to induce me to take part in the enterprise. At length, in

July, 1867, I bought fifty thousand dollars worth of stock and

became vice-president and general manager of the Peslitigo Company.

We began operations

on a large scale. The fifty thousand acres of timber lands which the

company had when I assumed direction of its affairs were increased

to one hundred and twenty-five thousand in the course of the next

five or six years. In addition to the water-mill at the village of

Peslitigo we erected at the mouth of the river a steam mill, the

largest and most complete establishment of its kind in the West. The

two had a combined capacity of from fifty to sixty million feet of

lumber a year, and on the first day of the operation of the new

plant, the men, in a working day of eleven hours and using selected

logs and putting forth their best efforts, sawed approximately

350,000 feet of lumber and 53,000 lath, a record for that time.

In 1868 we began the

erection of a factory for the manufacture of wooden pails. There

were two of these already in Wisconsin, one at, Two Rivers, owned by

Mann Brothers, and another at Metiasha, owned by E. D. Smith, whom

we induced to take an interest in our enterprise. We also entered

upon the manufacture of broom handles and clothes pins under the

direction of a man, whom we brought. from New Hampshire, reputed to

be the most skillful in the country in this branch of industry. The

magnitude of our operations may be gathered from the fact that at

one time we had in the yards drying two and one-half million feet of

basswood boards to be made into broom handles. In addition we built

twenty drying-houses, two large warehouses,— one of them three

hundred feet long and five stories in height,— and smaller

buildings. At Chicago we maintained a large lumber yard, and used

for the storage of woodenware the old sugar refinery on North Point.

Mr. Ogden also contemplated the establishment of a large tannery and

took up negotiations with one of the largest firms in New England

for that purpose, but before the plan could be carried out the great

fire in 1871 intervened.

Our work, however,

consisted of much more than the erection of buildings. The problem

of transportation still confronted us. It was necessary for us to

bring our manufactured products to the bay from Peslitigo, a

distance of seven miles, to construct a harbor where vessels could

be loaded, and to ship it thence to the market at Chicago. This

involved many difficult problems.

A railroad from the

village to Green Bay, equipped with locomotives which we obtained

from the Northwestern Railroad and transported on scows, provided

the first link. At the mouth of the Peslitigo River a private harbor

was made by driving piles out to deep water and filling in the

intervening spaces with slabs and edgings. This plan proved so

successful that it attracted the attention of the government

engineers who for three or four years came to make an annual

inspection; and, becoming convinced finally of the value of the

methods we had followed, adopted them for the construction of many

of the piers and harbors at lumber ports.

The transportation of

the lumber and other commodities to Chicago presented greater

difficulties. The railroad did not extend beyond Green Bay city and,

besides, the freight charges were prohibitive. On the other hand,

the cost of carrying lumber on ships was excessive. To reduce this

item of expense it occurred to me to use barges, a decided

innovation, as it was thought impossible up to this time to tow

these craft on the rough waters of Lake Michigan. We purchased two

tugs: the "Reindeer," which was brought from New York by way of

Oswego, and the "Admiral Porter," a larger vessel, which came

through Canada by way of the Welland Canal. Subsequently we disposed

of the "Porter" because it was not strong enough for our purposes,

trading it for a larger boat.

The barges we had

built at the shipyard at Trenton, near Detroit. There were six in

all, three with a capacity of one million feet of lumber each and

three that carried half this amount. These we proposed to tow in

pairs. While one of the larger and one of the smaller vessels were

in transit, another pair was at Chicago unloading and another at

Peshtigo taking on cargo. From the very outset the plan worked

successfully. Thus was established the first barge line on Lake

Michigan.

Having accomplished

this much, we decided to enlarge the tows and I went to Cleveland,

Detroit, and Bay City to purchase more barges to avoid the loss of

time required to build them; but there were none suitable for our

purposes. At this time there was only one barge line, a very small

one, on the lower lakes running from Bay City to Cleveland. The

captain of of the tug "Prindiville," —heralded abroad as the best

vessel of its kind in these waters,— who had charge of the line,

contended that barges could not be successfully towed on Lake

Michigan. When he left Bay City, he said, he encountered rough water

for a distance of only fifty miles and, if the wind were unfavorable,

he turned back. From the mouth of the river to Cleveland he was

exposed to rough weather for another fifty miles. His experiences

with these short stretches convinced him that towing on the open

lake where contrary winds and storms prevailed was an impossible

feat. He was somewhat taken aback when I informed him not only that

it could be done but that we were actually doing it successfully.

Our example was soon

followed by others. After we had operated our barges from Peslitigo

to Chicago for two years, four companies on the Menominee, including

the N. Ludington Company, which was still under my direction,

adopted the plan and we purchased the barge line operated by Theisen,

Filer and Robinson, of Manistique, Michigan. Extensive additions

were made to this equipment and in two or three years we had fifteen

barges in operation towing five at a time. We instituted another

innovation on Menominee by designing the tug ''Parrot" for the use

of slabs as fuel. On this item alone we effected a saving of five

thousand dollars a year. The vessel carried one hundred cords of

this wood, which was then inexpensive, sufficient to make the round

trip from Marinette to Chicago.

The establishment of

the barge lines raised the problem of signaling passing vessels,

especially during the night or in foggy weather when there was

danger of colliding with the tow. The usual signal of one whistle

gave warning of the approach of the tug, but not of the barges

behind. A number of years later, in 1884, when I was a member of the

House of Representatives, I filed with the Secretary of the Treasury

a petition recommending the adoption of a special signal for a tow.

Of the nine supervising inspectors of the Bureau of Navigation four

were in favor of the proposal and five opposed to it. I thereupon

took up the question directly with Judge Folger, then Secretary,

explaining to him the conditions, and pointing out the danger to

navigation not only from our own barges but from the tows of logs

which were brought from Canada in booms. Fortunately he had been on

Lake Michigan the year before and, while on his way from Chicago to

Sturgeon Bay on the revenue cutter "Andy Johnson," had met our tow.

He easily understood the situation and it was not difficult to win

him over to my position.

I proposed a signal

of three whistles at short intervals. He issued the order despite

the disagreement among the inspectors, and it was adopted. It has

always been the occasion of much satisfaction to me, not only that

my recommendation was followed, but that the signal is used to-day

in all waters under the jurisdiction of the United States and has,

possibly, obviated many dangers and saved many lives.

The progress we made

in the improvisation of new methods and the reduction of the cost of

transportation has since dropped into the background, and these

achievements are largely only of historical interest. With the

advent of the big steel freighters, the development of railroads,

and the establishment of important terminals, the entire problem has

been transformed and even the old wooden vessels are disappearing.

At the time, however, what we did was of great value not only to

ourselves but to others and perhaps it was but a step in the

direction of all that since has been attained.

Another important

improvement in connection with water transportation to and from

Green Bay which, though accomplished in later years, I may mention

here, was the construction of the Sturgeon Bay Canal, an artificial

channel across the peninsula jutting out into Lake Michigan from the

northeastern part of Wisconsin. Before the completion of this

waterway it was necessary for vessels from Green Bay ports to make a

wide detour around the barrier by way of Death's Door, the rocky

passage between the islands at the northern extremity.

The project of

building a canal across the narrow neck of land at Sturgeon Bay

called the portage had been under discussion for some years, but

nothing was done until the Peshtigo Company took the initiative in

the formation of a corporation to undertake the work of

construction. At the outset obstacles were encountered. The general

rate of interest on money was ten per cent. People who were expected

to take an interest in the completion of the improvement assumed an

attitude of indifference and declined to contribute to the fund we

attempted to raise for a preliminary survey. In Green Bay, the city

which was to be most benefited by it, the only subscription we

obtained was five dollars from one of the prominent lumbermen.

Nevertheless a

preliminary survey was made, largely through my efforts and at my

expense, but the route contemplated was abandoned because of the

discovery of a ledge of rock at the eleven-foot level, an

insuperable obstacle because the use of dynamite for under-water

blasting was unknown at the time. Later I succeeded in having the

government engineers make another survey for a route a mile and a

half in length. This was adopted, a grant of two hundred thousand

acres of land, odd sections lying for the most part in Marinette

County, was authorized and the company began work in the early

seventies.

General Strong,

secretary of the Peshtigo Company, Mr. Ogden, Jesse Spalding, and

myself had charge of the enterprise; but the actual direction of the

affairs of the corporation fell largely to me, as the others were

without the practical knowledge needed for work of this kind.

About midway in the

work of excavation we encountered a ridge, thirty feet above water

level, covered with a heavy growth of timber. In removing this we

came upon a cedar tree, fourteen inches in diameter at the butt,

buried under forty-three feet of earth. How long it had been there

is, of course, a matter of speculation. But in view of the depth of

the soil above it and the size of the trees that had taken root

there it seemed probable that it had been covered for two or three

centuries or more. In spite of its great age every branch, even the

bark, was perfectly preserved; and so great was the curiosity

aroused over it that we sent sections to various parts of the

country for examination, and scientists endeavored to solve the

problem of its antiquity.

The discovery

confirmed the conclusion I had reached several years before: that

cedar resisted decay much more effectively than other woods of the

northern region. While making repairs on the company's railroad from

the village of Peshtigo to the bay I found that a cedar tie, which

had been used inadvertently, was in a much better state of

preservation than others adjoining it, although they had all been

laid at the same time. This gave me the clue that was borne out by

the cedar tree unearthed in digging the canal, and I proposed to Mr.

Ogden and other railroad men that cedar, which was of little value

at the time for other purposes, be used for ties. My suggestion met

with opposition. Mr. Ogden contended that it was too soft, but

eventually he yielded to my judgment, others followed our example,

and in time the cedar tie became one of the staple products of all

northern lumbering establishments.

The canal was carried

through to completion as expeditiously and economically as any work

ever undertaken under like conditions; harbors were constructed and

the waterway was opened to traffic in 1873. The two hundred thousand

acres of land granted the company was at the time of little value.

Most of it was swampy or boggy and it had been for the most part

stripped of timber. We disposed of it at two auctions, at one of

which we sold 77,000 acres for $38,000. At present the tract would

be worth millions, but no one foresaw the agricultural development

that was to follow. In 1893 the canal was purchased by the

government for $103,000. |