|

THE Dunlop Street Theatre

had now been in existence for twenty-two years. During that period, the

city had changed its aspect. The ragged lanes and wasted patches were

now the sites of villas and pleasure grounds. St. Enoch Croft had grown

into a beautiful park, and Queen Street had become the fashionable

centre of residence, handsome villas lining the street. Glasgow, with

that taste for art which has made it so justly famous, felt that the

time had arrived for the erection of some edifice worthy to represent

the city's interest in dramatic art. From the commercial point of view,

it was deemed a feasible scheme to build a new theatre, and accordingly,

in 1804, at the extreme westward end of the city, in Queen Street,

operations were commenced. The position occupied was close to the

present

Royal Exchange, the

western boundary of the theatre running nearly in line with the North

Court, off Exchange Square. The committee of merchants included the

names of Laurence Craigie, John Hamilton, Dugald Bannatyne, William

Penny, and Robert Dennistoun. At the top of Queen Street West, was an

unsightly spot of earth, on which stood a decayed farmhouse. This

building was purchased from the Magistrates, as also a piece of ground

stretching northwards towards St. Vincent Place. The entire cost was

estimated at £18,500, and subscription shares were sold at £25 each. In

twelve months' time the building was completed, and for its description

we may be pardoned the use of Mr. Baynhain's account in his admirable

epitome of The Glasgow Stage.

"The front was

composed of an arcade basement, supporting six Ionic columns, 30

feet in height, with corresponding pilasters, entablatures and

appropriate devices. The principal vestibule led to the boxes by a

double flight of stairs, and was separated from the corridors by a

screen interspersed with Corinthian columns. The proscenium was

thirty feet wide and decorated with antique ornaments, and the stage

balconies were tastefully executed."

Seating 1,500 people, the

house was supposed to hold £260, the yearly rental being fixed at

£1,200. Upon its boards, in due course, appeared some of the greatest

stars of the day—the Kembles, the erratic Cooke, Kean, Macready, Munden,

Mathews the elder, Mrs. Siddons, Miss Farren, handsome Jack Bannister,

Mrs. Jordan, Dowton, Fawcett, Elliston, Braham, Liston, Miss Stephens,

Charles Mayne Young, Sinclair, Miss Tree, Catalini, Emery, (grandfather

of Miss Winifred Emery), and Mrs. Glover.

In speaking of the Queen

Street Theatre, any history would be incomplete that did not mention the

Black Bull tavern, so famous for its rendezvous. The tavern stood in

Argyle Street, at the corner of Virginia Street, on the site of Mann

Byars & Co's warehouse. It remained there up till 1858, after an

existence of eighty years, and during that time it had been the

discussion club for city politics, city improvements, hunting, theology,

and the drama. It was the home of all clubs of repute, and under its

roof foregathered the leading lights of the political, commercial,

sporting, and dramatic world, in the old days when men drank hard and

were less respectable, but more reputable. Here, too, Jackson and Aitken,

the old managers of the Dunlop Street house, must have negotiated their

application for the management of the new theatre. And successfully, as

it proved, for the theatre was let to them provisionally, upon their

promising to secure the very best histriones for the new house. That

famous comedy, The Honneymoon, the swan song of the unfortunate Tobin,

was the opening play. After passing through all the drudgery of "the

unaccepted," tired out with waiting, and sick at heart, he had gone on a

voyage for health. In his absence, his brother had been successful in

placing it on a London stage, where it became the talk of the town. But,

alas for the vanity of human wishes, when the news was carried to the

ship as she arrived at a West Indian port, the unfortunate Tobin was

beyond the reach of any human agency. The play produced an equally

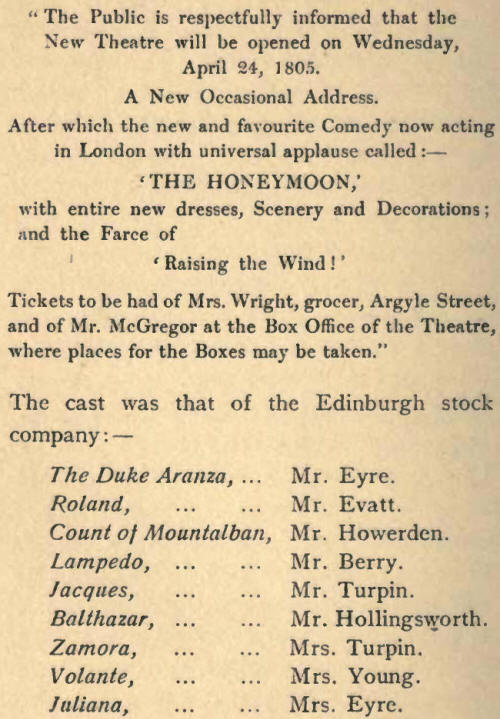

successful impression in Glasgow. The opening bill read:—

There were only four

performances given per week—on Mondays, WVednesdays, Fridays, and

Saturdays.

The first star to perform

here was Miss Duncan (Mrs. Davidson), the original Juliana. of The

Honeymoon, who appeared on June 24th as Lady Teazle. Shortly after this,

Harry Johnston occupied its boards. Previously, he had filled a short

engagement with Jackson at the Dunlop Street house. Born at Lanark, and

reared in London, he made his first appearance as an actor at the age of

eighteen. His first big success was made at Edinburgh in Home's Douglas,

in which he appeared as young Norval. Just at that time the revolution

in stage costumes had commenced, and Johnston chose the occasion to

dress somewhat differently from his predecessors in the part. Formerly

it had been played in trews and Scots jacket. Johnston donned full

Highland costume—kilt, breastplate, shield, claymore, and bonnet, and,

on his first appearance, was greeted with thunderous plaudits. The

Edinburgh public considered him the best Scotsman they had ever seen on

the stage. His style was largely moulded upon that of G. F. Cooke, of

whom he was not entirely unreminiscent.

Aitken, having now

seceded from the management, Jackson entered into partnership with an

actor named Rock, only to find his invariable fate pursue him. Within

twelve months of his taking over the management of the theatre, the end

of all came, and poor Jackson, ruined in health and wealth, went over to

the great majority.

It was not till June of

1807 that the first real star came to Queen Street Theatre, when George

Frederick Cooke, "the greatest living actor of the day," was billed to

appear. Opening in Richard III., he appeared as Peregrine in John Bull,

Petruchio in Taming of the Shrew, and Sir Pertina MacSycophant in The

Man of the World. Intense excitement prevailed during his visit. His

reputation was unique: he was one of the greatest drinkers of his day.

He had reached the age of forty-five before he took London by storm as a

Shakespearean actor, and that in the character of Richard III. This took

place at Covent Garden, where the directors gave him a free benefit, the

profits of which amounted to over £560. Macready writes of him:

"My remembrance of

George Frederick Cooke, whose peculiarities added so much to the

effect of his performance, served to detract from my confidence in

assuming the crook-back tyrant. Cooke's varieties of tone seemed

limited to a loud harsh croak descending to the lowest audible

murmur: but there was such significance in each inflection, look,

and gesture, and such impressive earnestness in his whole bearing,

that he compelled your attention and interest. He was the Richard pf

the day, and in Shylock, Iago, Sir Arch. MacSarcasm, and Sir

Pertinax MacSycophant, he defied competition. His popularity far

exceeded that of Kemble."

Cooke's drinking habits

often led him into amusing contretemps with his audience. Upon one

occasion, when he was being constantly interrupted by a young officer in

the stage box, Cooke, stopping the play for a moment, went close up to

him, and addressed him thus: "D---- you, sir. Sir, the King (God bless

him) can make any fool an officer; but it is only the great God Almighty

that can make an actor."

Once in a public house he

quarrelled with a soldier. "Come out," roared Cooke, "and I'll fight

you." "You're a gentleman," pleaded the soldier; "you've money, and

everybody will take your side." "Look ye here," cried Cooke, turning out

his pockets, "here's £300, all I have in the world—there," and

staggering towards the hearth, he threw the bank notes into the fire.

"Now, I'm as poor as you: come out and fight, you villain."

Time after time the

public would read the announcement that Mr. Cooke could not appear in

consequence of "a sudden serious indisposition." Upon his appearance

after these intimations, he would be greeted with cheers, groans,

laughter, and cries of "Apology." Stepping forward with a solemn stride

and a mournful look, he would bow very low, and, with hand upon his

heart, make the invariable speech, "Ladies and gentlemen, I have had an

attack of my old coin plaint." The appeal never failed to set his

audience into a good humour again. He died in New York. At his final

performance there, his memory having failed him in the Fair Penitent, he

was forced to withdraw. When he came off the stage, he said, "I knew how

it would be. This comes of playing when I am sober."

In 1814, the management

of the Queen Street house came into the hands of the ever-popular Harry

Johnston, who had now become notorious as the man who thrashed the

Prince of Wales. The incident is worthy of mention. The future George

the Fourth had presumed to force his way into Mrs. Johnston's

dressing-room at Drury Lane. Johnston followed him quietly, and

administered a sound horse whipping. He was placed in custody, but

managed to escape; then, disguised as an old soldier, he left London on

foot for Newcastle. Later, having failed as a director of the Dublin

Theatre Royal, he came over to the Queen Street Theatre, which he

managed for a year. In his later days he was compelled, through

persistent bad luck, to live upon the kindness of his brother actors,

till he died at Lambeth. Twelve months after the Drury Lane escapade,

his wife figured in the Divorce Court, the co-respondent being the

celebrated orator and Deputy Master of the Rolls, Richard Curran.

On the 10th March, 1815,

Edmund Kean made his first appearance here under Johnston's regime. The

scene was a memorable one. All the boxes were taken a week before, and

temporary ones had to be erected on the stage. The professors from the

University and all the litterati of Edinburgh, including Francis

Jeffrey, were present, and a phenomenal crowd, which completely barred

all passage through Queen Street, had been waiting for hours before the

time of admission. Upon his second visit, in April, his repertoire

included Richard III., Othello, Sir Giles Overeach, Romeo, Penruddock

(Wheel of Fortune), and Zanga in The Revenge.

But his visit in 1820 was

not attended with the same friendly auspices. Having figured in an

action for divorce, as co-respondent, the plaintiff, Alderman Cox,

secured damages against Kean. To do Kean every justice, it was alleged

that the affair had been prearranged to extort heavy damages from the

actor. The press had been unanimous in denunciation, and the public,

taking up the cry, hissed him whenever he appeared. While resting at

Bute Cottage, Rothesay, he was Offered an engagement at Queen Street,

and opened up there for a six nights' appearance with Richard, when a

house crowded with men and boys greeted him, no women being present. Not

a word of the play was heard, the piece being acted in dumb show. The

performance of Othello met with as little success, and Brutus fared

little better. Wednesday being his last night, he, in response to the

cheering, made a speech: "Ladies and gentlemen. When I used to visit

this city, it was always a rich harvest to me, but this time, there has

been a great falling off. That, I suppose, is owing to a certain event

which has already cost me £999 more than it was worth. I am going to

America (cries of "No! No!") to perform again. if I ever return to this

country I shall certainly pay you a visit, for old kindness I never

forget. For the present I bid you a respectful farewell." When he

returned in September, he was well received, although no ladies were

present in the audience.

His next engagement, in

1827, was memorable to Kean, for the news that his son Charles would

make his debut at Drury Lane on 1st October. Previously he had said, "If

Charles tries to be an actor, I will cut his throat. I will be the first

and last actor of the name." He was playing Reuben Glenroy in Town and

Country when he heard the news, and he was unable to finish his part.

However, the tender heart of the parent came out, for he sent Lee up to

London to see " how the boy got on," and received the gratifying message

that Charles had been fairly successful.

It was in 1828 that the

new star, Charles Kean, came to Glasgow, but he did not meet with an

altogether gratifying reception. Coming to personal matters, Charles did

not .approve of his father's selection of a disreputable companion, who

was living with Kean at Bute. Meantime, the manager, in his desire for

good business, hit upon a plan to draw the crowd. He persuaded the elder

Kean to accept a one night's engagement, studiously avoiding to tell him

that it was for his son's benefit, or that they were playing together.

Lee tells the story:

"Kean got into a

terrible passion upon making the discovery, and wanted to leave the

house; but he was urged not to show spite against his own son, and

persuaded to go on. The tragedy was Brutus, Kean playing the title

role, and his son, Titus, when the Theatre Royal held the largest

audience it had ever seen. In the wings and on the stage itself

there were 250 persons. Only when the father was passing out on his

way home did he speak. 'I hope to see you, Charles, at Bute

to-morrow There will be it crust of bread and cheese for you there.'

To which Charles politely replied, 'Thank you, Father,' but never

went, going to Belfast instead."

Five years afterwards,

they met on the boards of Covent Garden, Kean appearing as Othello to

Charles' Iago. The elder made some friendly advances, and everything

went well till the third act, when he came to the celebrated speech,

"Villain," at which words Kean's voice broke down, and, falling upon his

son's shoulder, he whispered, "Get me off, Charles, I'm dying. Speak for

me." He died two months afterwards at Richmond, 13th May, 1833.

Springing out of bed, with the old fire upon him, lie cried, "A horse, a

horse, my kingdom for a horse!" and his last words were taken from the

dying speech of Octavia in The Foundling of the Forest. "Farewell,

Flo-Floranthe."

The next big engagement

was that of Miss O'Neil (21st August, 1818) in Venice Preserved, in

which she appeared as Belvidera. For this attraction the prices were

raised, which caused a somewhat tumultuous audience to hiss Johnston,

but in the end their better nature prevailed.

A novelty was announced

for 18th September, 1818:-

"Grand Crystal Lustre

of the front Roof of the Theatre, the largest of any of this time in

Scotland, will in place of the Wicks and the Candles and the Oil

Lamps be Illuminated with Sparkling Gas."

A phenomenal audience

greeted this innovation, the house presenting a brilliant appearance

with the elite and generality of the city arranged in its best finery.

The band struck up the National Anthem, the audience joined in the

chorus, when, as if by magic the gas was turned on, "leaving some of

them to fancy that they had been ushered into a new world—a perfect

Elysium on earth."

The programme on this

occasion consisted of Mozart's Don Giovanni, with John Corri conducting,

and a company of Italian artistes.

Although the fact is not

generally known, Rob Roy was produced in Glasgow nine months previous to

its Edinburgh performance. This was for the benefit of W. H. Murray, of

the latter city, on June 10th, 1818. Murray played the Bailie to the Rob

of Yates (the father of the late Edmund Yates). The event remained

unnoticed by the local press, although the play enjoyed a run of four

nights.

In 1817, Sheridan Knowles

came to Glasgow with his father, and taught elocution at his classrooms

in Reid's Court, off the Trongate. John Tait, the theatrical printer and

bill inspector, two years later introduced him to Macready. Knowles was

never a thrifty man, and, though he was getting two guineas per session

from his pupils, he was always in strained circumstances. Scenting a

possible means of raising the wind, he got Tait to despatch his MS. of

Virginius to Macready. The idea was a successful one. Macready accepted

it and paid him £400 for a twenty nights' run. Twelve years afterwards

found Knowles still as impecunious. Then he wrote The Hunchback, sent it

off to the same manager, and it was at once accepted. In rehearsing it,

Farren was stricken down with paralysis. Kean was too old to act, and

Macready himself declined the part. In despair, they sent for Knowles,

who played the part of Master Walter, and the piece became the hit of

the season. But Knowles was never fully appreciated by the Glasgow

public. When, at the end of one season, he starred with Miss Ellen Tree,

and the curtain rose on his William Tell, there were only fifty people

in the auditorium. A Glasgow critic wrote of him:

"He is an actor

though not of the very, highest class. He could not for a moment

measure spears with Kean, but with most other living performers he

need not fear comparison."

James Aitken (the father

of Miss M. A. Aitken) made his debut as Macbeth on 13th February, 1820.

He was the son of a York Street upholsterer, and had been a divinity

student, having in the course of his studies taken elocution lessons

under Sheridan Knowles.

Amongst those who were

present at his first appearance were Dr. Chalmers and Edward Irving.

Macbeth proved a big success, being repeated nine times during the

following three weeks. The part in which Aitken was best remembered was

Vanderin' Steenic in the drama of The Rose of Etrick Vale. Through all

the vicissitudes native to this profession, he gradually sunk into the

part of walking gentleman at Covent Garden. Then he quarelled with John

Kemble, and returned to Glasgow to teach elocution. Combining this with

frequent appearances as a public reciter, he finally passed away in

obscurity. He died at Paisley on 19th September, 1845, having contracted

a. severe chill after a public engagement.

A powerful rival to the

Queen Street managers rose up in the person of Mr. Kinloch, who took a

theatre in Dunlop Street, then christened the Caledonian (1823), where

he produced the hit of those days, a play founded on Pierce Egan's Tom

and Jerry, making a clear profit on his season's work of £2,000.

The year 1825 brought the

eccentric J. H. Alexander before the Glasgow public. Having had a

somewhat varied career as tragedian, low comedian, character actor, and

heavy gent, he went into management at Carlisle, and in 1822 he took the

minor theatre hitherto managed by Kinloch. In 1825, hearing the

Caledonian Theatre was in the market, he resolved to secure it. Seymour,

the stage manager at Queen Street, managed to forestall him, and

obtained possession. When Alexander arrived, he discovered he was too

late, but it was not long before he had completed his plan of campaign.

The building was not wholly occupied. Underneath was a cellar tenanted

by a cotton dealer and potato merchant. Settling terms with this man of

business, Alexander took up his abode therein. Seymour opened the

Caledonian upstairs with Macbeth. Meantime Alexander christened his

cellar "The Dominion of Fancy," and opened up the same night with The

Battle of Inch. In the words of Mr. Baynham:

"Macbeth was acted

nearly throughout to the tuneful accompaniment of the shouts of the

soldiery, the clanging of dish covers, the clashing of swords, the

banging of drums, with the fumes of blue fire every now and then

rising thro' the chinks of the planks from the stage below to the

stage above. The audience laughed, and this stimulated the wrath of

the combative managers. Any new sensation will draw an audience, and

the fact of getting extraordinary effects unrehearsed, and certainly

never seen before, drew large audiences."

The rivals besought

magisterial aid to save themselves from each other, with the result that

Seymour was allowed to open four nights a week, and Alexander two

nights, Saturday and Monday, the best of the whole week. An appeal to

the Court of Session only brought a confirmation of the Magistrates'

decision. Then the struggle for supremacy took place. When "The Dominion

of Fancy" opened, its performance was subordinated to the noise of a

brass band playing upstairs in Seymour's house. Following upon this came

another appeal, and the instructions that "Neither party was to annoy

the other, and, on any more complaints being brought, both places would

be ordered to be closed."

Seymour's people next

lifted the planking and poured water on the audience below. The climax

was reached at the production of Der Freischufz, which was staged by

both houses. Seymour's party mustered in strong force and took full

advantage of the gaps in the planks to spoil the performance below. In

the incantation scene, the dragon could not spit out his fiery fumes,

and he was held by the tail till his fire had burned out. The

skeleton-hunters were disturbed in their wild career: the curtain could

not fall, and the cast had to be told to come off the stage. The magic

circle was broken; Zaniel and his skeleton horseman had to walk off with

the rest. To complete the devastation, the curtain came down with a

crash, and the accompanying volumes of dust nearly suffocated the

spectators. So ended this tale of rivalry. But it was not a failure, by

any means. The public deserted the Queen Street Theatre and came to see

the fun. Toni and Jerry ran for a month, being played at both houses

simultaneously during one of the weeks. And after such events who shall

say that the Scots lack any sense of humour!

The late proprietor of

the Theatre Royal, Queen Street, having disappeared with the keys of

that house, leaving behind a bill for six months' rent, the entry of Mr.

Frank Seymour could not by any manner of euphemism be called an

impressive one. This gentleman was compelled to go through the

green-room window to open the door of the theatre.

Opening with Liston in

Kennedy's comedy, Sweethearts and Wives and the farce, X. Y. Z., the

engagement proved so successful that he determined to renovate the

place. During the progress of these repairs, the company played at the

old, quarters in Dunlop Street. When the re-decoration was completed, he

opened with a strong bill consisting of that hardy perennial, Rob Roy.

One of his most successful shows was the production of Aladdin, on 10th

May, 1826, for which the attractions were eighteen new scenes, a

military band, fifty supernumaries, magic properties, and a flying

palace built on a platform thirty feet long by eight feet broad, one of

the biggest hits of the Glasgow stage. Another notable engagement was

that of Andrew Ducrow, who brought a double company of a hundred ladies

and gentlemen, a stud of forty horses, pack of hounds, and a stage for

the equestrian spectacle, "A Stag Hunt." The house was burned down on

10th January, 1829. The proprietor's losses were largely covered by

insurance, but a sum of £2,000 was lost through destruction of music,

books, papers, etc. A ball was given at the Assembly Rooms, Ingram

Street, at which £1,000 was realised for the benefit of Seymour.

On 2nd October, 1829,

Seymour opened a new house in York Street, for which he claimed the

patent of the Theatre Royal. His opening star was Edmund Kean, in the

part of Shylock; Braham, Rae, Macready, and a host of others following

in succession. The experiment was a failure, however, the York Street

house remaining open only during a period of eighteen months.

Meantime J. H. Alexander

had returned to Dunlop Street, and, after having made vast alterations

in that house, opened his season with Dimond's Royal Oak, or the Days of

Charles the Second, himself playing the part of the King. It was during

this season that he again came into rivalry with his old opponent,

Seymour, at the York Street Theatre. It was Alexander that scored this

time. He managed to secure the stars, such as Vandenhoff, Miss Jarman,

T. P. Cooke with his nautical dramas, Liston in Paul Pry, Mackay in the

favourite parts of his repertoire, Bride of Lammerrnoor, Gilderoy,

Crainond Brig, Guy Mannering, and in his memorable Bailie Nicol Jarvie.

Harry Johnston, F. H. Lloyd, and the Siamese twins appeared at Dunlop

Street during the same year. Kean played in Othello and several other

plays. Concerning the last named, Mr. G. W. Baynham tells a rather

interesting story:-

"The Iago to his

Othello was an old actor called Willie Johnstone. Johnstone was very

rheumatic. Kean was also weak in the legs. In the business of the

third act both actors knelt in front of the stage, and neither of

them found it possible to get up again. On Iago saying to his

general, ' Do not rise yet,' Kean was heard to mutter, ' D----d if I

think I ever shall rise again.' Both gentlemen remained, unable to

move, until Kean managed to raise himself by clinging to his ancient

friend, in which endeavour both nearly rolled over together, the

gallery boys meantime applauding vociferously, and shouting, 'Try it

again, Willie, try the other leg. Now faut haun's and knees.' At

last, Mr. AIexander, who was playing Roderigo, taking pity on poor

Willie, came on the stage and placed him safely on his feet, amid a

cry from the gods of ' Houp-la,' and a round of applause for his

humanity."

When one has noted in

1836 the appearance of G. V. Brooke (then a humble member of the stock

company), the visit of Charles Mathew the younger, and the advent of a

formidable rival in the person of Ducrow, who, emboldened with the

success of his London show (Astley's old circus), opened an arena in

Hope Street, until the year 1842, nothing of unusual prominence

occurred.

In February of that year,

Mr. and Mrs.

Charles Kean commenced a

fortnight's engagement. Kean was somewhat undersized, his head was

large, his legs rather thin, and his voice had an unfortunate huskiness

of tone. In addition to this, he experienced some difficulty with the

consonant M, which he sounded like B, and N like D. As an example of

this, one of his opening sentences became, "Bost postedt g—r—rave and

r—r—everend scidaors." But the grace of his gestures, and the effects he

obtained by the use of his brilliant dark eyes, quite overcame these

defects, and conquered the hearts of his audiences. It is of him the

familiar story is told:

In Richard the Third

his best point was, Off with his head, so much for Buckingham.' On

one occasion he was disappointed in its delivery. In the scene where

the capture of the Duke of Buckingham is announced, the messenger

should say, `My lord, they have captured Buckingham,' but the actor

was somewhat nervous, and in his flurry said, 'My Lord, the Duke of

Buckingham is dead.' FlummoxedI' exclaimed Kean, using his favourite

expression. 'Then what the d are we to do with him Flow.'

In this year D. P. Miller

announced the opening of the Adelphi Theatre, stating that he would

retain so good an ordinary company that no stars would be required. He

opened with Richard the Third, W. Johnston playing title role and John

Grey the part of Richmond. The circumstances which led to Miller's

adopting the theatrical profession were peculiar. In 1839 he was a

showman at Glasgow Fair, conducting a' conjuring booth which stood

opposite to Anderson's, "the Wizard of the North," who was then coining

money with his Great Gun Trick. Miller copied the trick, charging one

penny admission, where Anderson charged sixpence. The profit which he

gained from this enabled him to commence the Adelphi. His greatest hit

was a performance of As You Like It, with Miss Saker as Rosalind. This

lady in the course of events became Mrs. R. H. Wyndham. The Touchstone

on this occasion was Henry Lloyd.

To the Adelphi belongs the honour of Phelps' first Glasgow appearance on

14th February, 1843, when he essayed the part of Hamlet. His visits to

Glasgow were very few, although he was always a favourite in that city.

His Iast performances there were the Bailie and Sir Pertinax

MacSycophant, the latter being considered one of the finest

interpretations of the part.

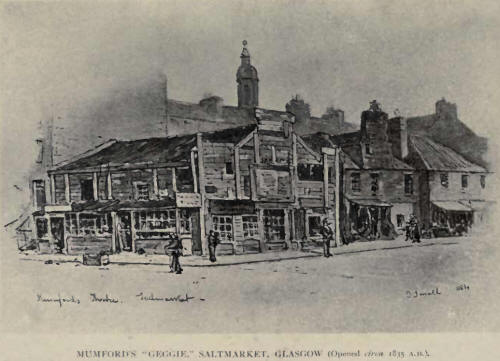

Perhaps at this juncture

a reference to that historical institution, beloved of our grandsires,

Muinford's Geggie, may not be inopportune. Its owner was a Bedfordshire

man. As a child he was far ahead of his playfellows. He constructed a

dress for himself made solely of straw, and this led to his being

regarded as the lion of his native town. Flushed with his success, he

took the road to London, where he exhibited in the open air. After being

constantly worried by the police, he set up a marionette show, and, at

the end of his travels, he finally landed in Glasgow, where the pristine

youth of that city regarded him as a public benefactor. But a periodic

worship of the bottle fiend would sometimes lead to weeks of enforced

absence. Upon his return, he would often give an open-air address on the

temperance question. "If you knew," he hiccuped one day, as he supported

himself by one of the posts of his show, "if you knew the

advantages to be derived from abstaining from intoxicating drink, you

would shun whisky (hic) as you would the very devil." "You're drunk

yourself! " said one of the crowd. "I know it," said Mumford, "but what

did I get drunk for? Not for my own gratification, but (hic) for your

profit, that you might see what a beast a man is when he puts an enemy,

to his lips. I got drunk (hic) for your good."

Alexander, finding out

that Mumford's Show was interfering with the rights of his patent,

obtained an injunction against him, which resulted in the closing of the

"Geggie."

It was in the month of

May, 1843, that Edmund Glover brought his Edinburgh company, seventy in

all, to the Dunlop Street house, where, amongst other things, he played

Romeo and Petruchio.

On December 11th of the

same year, Helen Faucit made her debit at the Theatre Royal. Her initial

performance was Pauline in The Lady of Lyons, and, during her seventeen

nights' engagement, she appeared in the parts of Juliet, Rosalind, Mrs.

Hailer, and Lady Macbeth. Her farewell performance was given on December

5th, 1870, when she played Beatrice in Much Ado About Nothing. To

Glasgow she was the favourite actress, and to the last she was entirely

beloved, after an acquaintance of twenty-seven years with the audiences

of this city.

Returning to Alexander,

his salary list was a proverbially niggard one, and, as the years

passed, he became increasingly mean. During its existence, his stock

company could boast the names of such sterling actors as Glover, Powrie,

Paumier, Lloyd, Fitzroy, and Webster. It is said that, in The Hunchback,

Miss Faucit as Julia, Glover as Master Walter, and Powrie as Clifford,

were never equalled. Coming as she did from such a perfect stage manager

as Macready, Miss Faucit was inclined to be autocratic, and, as a

consequence, was never really loved by the professionals. Instances

occurred where she would be about two hours late for rehearsals, and

upon her arrival would insist upon the whole play being again rehearsed.

Every attention had to be lavished upon her. A large draught screen was

placed behind her, a cushioned arm-chair was provided, and during the

performance the green room, usually the common property of the cast, had

to be completely reserved for her use. She was a willing worker in the

cause of charity. Her last public appearance was at the St. Andrew's

Hall, where she gave dramatic readings in aid of the Fund for the

assistance of the City Bank victims.

At the Adelphi Theatre,

Miller opened up his second season in 1844, and now devoted himself to

the task of strengthening his stock company. His leading man was Tom

Lyon, the London Adelphi favourite; Melloure, low comedian; and Stark

and M'Gregor, Scotch comedians. On his list of stars appeared the names

of Graham, Lloyd, Sheridan Knowles, and Mackay, the last named as the

Bailie, a fact which was facetiously announced that he "now appeared for

the first time in his ain locality, the Sautmarket."

Christmas of 1844 saw the

production of Cinderella, admittedly one of the best spectacles Glasgow

had ever witnessed. The pantomime included the famous Leclercq family—M.

Leclercq, the ballet master; Charles Leclercq (late of Daly's company);

Arthur Leclercq, famous as a clown; Louise, the dancer; Carlotta and

Rose Leclercq, with whose death some years ago passed away the last of

the "grandes dames," a special character line, peculiar to fin de

siecle drama.

In this year, Alexander's

company included Miss Laura Addison, who became leading lady with Phelps

at Sadlers Wells Theatre. When Alexander produced Rob Roy, with Paumier

in the title role, he himself assumed the part of the Bailie, somewhat

unsuccessfully, as it was pronounced to be a pale echo of Mackay's

impersonation. An excerpt from the then existent Dramatic Review says:—

"The whole time Mr.

Alexander was on the stage lie was directing everybody, players,

scene shifters, and gas-men, saying, for instance audibly, 'Come

down here, sir.' `Stand you there, sir.' "MacStuart, that's not your

place.' 'Keep time with the air as I do.' 'Hold up your head, sir.'

'Speak out.' Never for a moment did he allow the audience to forget

that he was manager. He beat time to the orchestra; he spoke to the

musicians; he sang the music for other people, and he spoke their

words. In theatrical parlance, his greatest delight was 'to show the

company up.'"

A more notorious episode

occurred at a performance of Julius Ceasar. Alexander was playing

Cassius, when a gentleman in the boxes commenced to titter at him. The

manager paused and glared at the auditor, but ineffectively. Then

Cassius stepped forward: "I must request the gentleman to pay more

attention to good manners and to the feelings of the audience. I can't

have the entertainment spoiled by the disgraceful conduct of a Puppy.

For myself, I consider I am quite competent to play the part I am

engaged in, and if that fellow in the boxes continues his annoyance, I

shall feel myself compelled to personally turn him out." The play was

then continued, but not for long. Again the laughter began, and Paumier,

who played Brutus, got over the footlights, climbed into the box, and

turned the offender out.

In the year 1845,

Anderson, "The Wizard of the North," made a bid for theatrical success

by building a splendid theatre on The Green and calling it by the name

of " The City Theatre." Having opened it during the Glasgow Fair for the

display of magic and for dancing, he afterwards applied for a dramatic

license. Though at first refused, it was finally granted, and on 7th May

he commenced with an Operatic company which included J. S. Reeves (Sims

Reeves) . In an endeavour to emulate the grandeur of The City Theatre,

Anderson had the Adelphi reconstructed at a cost of £2,000. His company

went to Edinburgh during these operations, appearing in the drama,

Cherry and Fair Star. In his absence from Glasgow, Alexander put into

force a form of arrestment, seizing the property and all available cash,

in lieu of payment of the unpaid law expenses of a previous prosecution.

Anderson's Theatre proved

a great draw. Sims Reeves and Morley both appeared in The Bohemian Girl,

in which it is reported "the tenor created a furore." Here Mrs.

Fitzwilliam from the London Adelphi charmed all beholders by her

performance in The Belle of the Hotel and in The Flowers of the Forest.

To him also came, as a member of the stock company, young Barry

Sullivan, whose articulation was very distinct, but who did not appear

to understand any character he attempted. On the night of November 18th,

1845, The City Theatre was totally destroyed by fire. Upon the same

evening, performances of Der Freischutz and The Jewess had been given.

In the conflagration everything was lost.

That there were

"superior" people in Glasgow in these days is evinced by the following

extract taken from the Dean of Guild Report, 6th July, 1849:

"Calvert, of the

wooden Hibernian Theatre, obtained authority to erect a new brick

edifice in Greendyke Street immediately to the east of the Episcopal

Chapel, and adjoining the Model Lodging Houses for the working

classes. Now that the Adelphi Theatre, the City Theatre, and Cook's

Circus have been all swept off the Green by fire in less than four

years, we have no doubt that this Hibernian will have `ample room

and verge enough' for dishing up the penny. drama for the

delectation and improvement of the canaille and young Red

Republicans of the Bridgegate, the Wynds, Saltmarket, High Street,

the Vennels, and the Havannahs. Since the house is to go up, the

Court wisely resolved to look to its security by appointing Mr.

Andrew Brockett, wright, to inspect it during its progress, and see

to its sufficiency."

The building was

Calvert's new theatre, which he christened "The Queen's Theatre."

With the year 1845

commences the records of the travelling companies, and with that our

history of the Glasgow stage should appropriately end. The first company

came from the Theatre Royal, Haymarket, and amongst its members may be

mentioned the names of Howe, Holl, Brindal, Braid, Tilbury, Coe, Little

Clark, Miss Julia Bennett and Mrs. Heunley. Someone has said that the

story of a people must be the history of its great men, and so with

equal relevancy one might say that he who would read the latter history

of dramatic Glasgow must read the records of Britain's theatrical stars

of the past and present generations, where the appreciation of the

Glasgow, audiences reads as one of the chief conquests they have made. |