|

TOM MORRIS was born, as

already mentioned, at St Andrews on the 16th of June 1821.

"You were born in St Andrews, of course?"

"Ay, an' I've lived in it a' my days, except for the years I spent when I

was greenkeeper at Prestwick. I was born in the North Street. My father was

a St Andrews man, employed as a letter-carrier. He played golf in his spare

time."

His father's name was John Morris, a much respected man in St Andrews in his

day. His mother was Jean Bruce, but so far I have not been able to find out

any particulars in regard to her parentage. She belonged to Anstruther. Tom

was born in a house on the north side of the west end of North Street, which

is still standing.

He was baptised by the Very Rev. Principal Haldane, D.D., Principal and

Primarius Professor of Divinity in St Mary's College, St Andrews, who was

also parish minister of St Andrews, or, more correctly, minister of the

first cl large of the parish of St Andrews. Those were the days of what were

known as "pluralities" in the Church of Scotland, and "The Doctor," as he

was familiarly called, would have a large income, which, being a bachelor,

he could not very well spend.

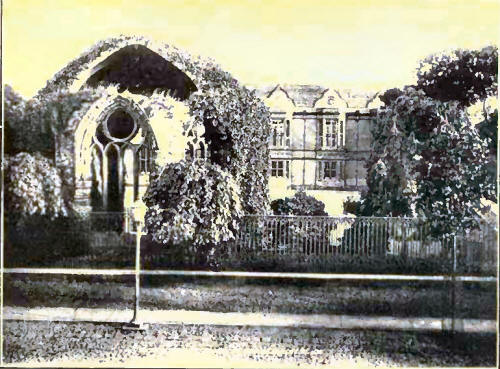

Blackfriars Monastery

Tom went for a short time to school, and attended the famous Madras College,

the history of which is given in Professor Meiklejohn's very able and

interesting life of its founder, Dr Andrew Bell, a book to which we

incidentally owe some of the best descriptions of St Andrews and some of the

most excellent comments on the game of golf we have. Mr, afterwards Dr,

Crichton was English master at that time, a predecessor of Andrew Young,

author of the popular Sunday School hymn, "There is a happy land, far, far

away," and of my own teacher and relative by marriage, Dr Robert Armstrong,

whose books on English composition and literature were well known in their

day. Besides attending Mr Crichton's classes, Tom probably would be a pupil

only of the then arithmetic and writing masters.

He began to handle a club as soon as he could toddle, and very likely his

first balls would be "chuckie stanes," with which the streets of St Andrews

abounded. By-and-by he would get as far as the links.

'I've played gowf close on eighty years, and that's longer than most folk

get living. I began on the links doon there as soon as T could handle a

club, and 1 have been doing little else ever since'.

My faither and mither lived in the North Street, and as soon as I could gang

I and the other laddies would be doon on the links with any kind of a club

we could get, and any old ball, or even a bit of one balls werena sac cheap

in thae days as they are the noo, though they're dearer again since the new

rubber-core ball came in."

"You would be grown up before the old feather balls were displaced by the

gutta?"

"That's true," he replied. "I began to play when I was six or seven, maybe

younger. You ken a' St Andrews bairns are born wi' web feet an' wi' a

golf-club in their hands. I wad be driving the chuckie stanes wi' a bit

stick about as sune's I could walk. When I left school I started how to

learn to make golf balls. They werena much like the golf balls we have now,

the old 'featherics,' but they could play fine afore the wind. I learnt to

mak' clubs and balls wi' Allan Robertson. I was busy making 'featheries'

when the gutta balls came into fashion, and a bonnie business he and I had

owre the change. Allan couldna abide the sight of the new ball at first. One

day I was out playing with Mr Campbell of Saddell, and I got stint of balls.

Mr Campbell gave me a gutta to try. Coming in, we met Allan, and somebody

told him that I was playin' a grand game with one of the new balls. Allan

said nothing at the time, but I saw he didna like it, and when we met in the

shop we had some words about it; and this led to our parting company, and I

took to making balls on

my ain account."

The gentleman who was the indirect cause of Tom setting up for himself was

Mr John Campbell of Saddell, in the Mull of Kintyre. He was a very handsome

man, and was one of the Knights at the Eglintoun Tournament. While a

bachelor he lived with Clan Ranald in Pilmuir Place. Clan Ranald was Æneas

Ronaldson Macdonell of Glengarry and Clan Ranald. He was one of the bucks of

the period and ran through his fortune. Mr Campbell of Saddell married Miss

M'Leod of M'Leod, one of the Queens of Beauty at the Eglintoun Tournament.

After their marriage they lived for a long time at The Priory.

There is a good account of him as a rider to hounds, and also a song he

composed, in Nimrod's Northern Tour, in which there are also notices of many

of the St Andrews golfers in Tom's early St Andrews days.

Here are how the two friends are depicted in Carnegie's "First Hole at St

Andrews on a Crowded Day":-

"I see the figure of

Clanranald's Chief,

Dressed most correctly in the fancy style.

Well-whiskered face, and radiant with a smile,

He bows, shakes hands, and has a word tor all

So did Beau Nash, as master of the hall!

Near him is Saddell, dress'd in blue coat plain,

With lots of Gourlays, free from spot or stain;

He whirls his club to catch the proper swing,

And freely bets round all the scarlet ring;

And swears by Amman he'll engage to drive

As long a ball as any man alive! "

Sir David Baird, Bart.,, of

Newbyth, was one of their cronies. He was a tall man, who played in a "tall"

hat "lum hat" as they are sometimes called. He was a first-rate and keen

golfer. Sir David Baird "can play with any golfer of the present day." He

was also a "mighty hunter" well known at Melton Mowbray, where he was killed

by his horse kicking him.

Another of their golfing allies was George Fullerton Carnegie of Pitarrow,

the laureate of golf of his day a Forfarshire laird, cadet of the great

Carnegie house Earl of Southesk a neat, little, smart man, who came a great

deal to St Andrews in those days. He had a long minority, and when he came

of age succeeded to a large accumulated fortune, besides being proprietor of

Charlton, within two miles of the links of Montrose. He was a "gay dog," and

spent his money somewhat extravagantly. He was a popular member of a

well-known Edinburgh fast set, who kept racehorses, betted, played high and

hunted a great deal.

Many are the stories told of the high jinks of these jocose and somewhat

boisterous bucks.

One night they had a great symposium in the Royal Hotel, Princes Street. The

Lord Glasgow of the day, then Lord Kelburn, was of the party. One of the

waiters had incurred their wrath, and by way of teaching him better manners

and securing better behaviour in the future, they chucked him head foremost

out of the window down into the area below. Someone, presumably the

long-suffering landlord, came in to tell them that they had seriously

injured the unfortunate man. "Put him in the bill," was the ready response

of these madcaps.

Mr Robert Clark, in his well-known book, Golf: A Royal and Ancient Game,

tells that "Carnegie in a very few years had his estate in the hands of his

creditors, and was under trust." He adds, "Before his reverse he married a

daughter of Sir John Council, and a characteristic story is told of his

manner of proposing."

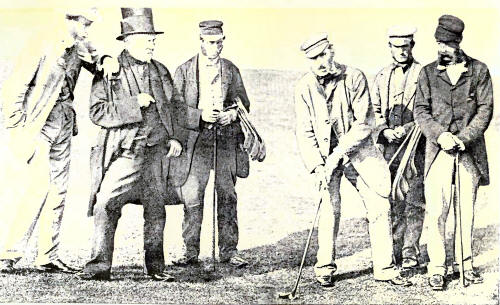

Characteristic Group in the 'fifties

Unfortunately, Mr Clark does not give us the story, and I should be very

much obliged if any of my readers would tell it to me. Notwithstanding his

habits, Carnegie was really a very clever man, of wide reading, and had a

large store of exact information. His golf poetic genius for it almost

amounted to genius is well known to golfers of the old school, and to

students of the literature of the game. He had a marvellous aptitude for

hitting off with real humour the characteristics of the players of the day.

Owing to the slightness of his figure and the shortness of his stature he

was known as "Little Carnegie." After the manner of many other little men he

liked to be with tall men, and was constantly with Campbell of Saddell,

Major M'Kenzie and Mr Fraser, who was six feet six inches. The gun with

which he used to shoot, and he was a capital shot, appeared to be as long as

himself. "Notwithstanding certain peculiarities, he was a thorough gentleman

in manner, and, though small, a manly, hardy man; he had no spare flesh, and

his muscles were whipcord. He had a passion for golf (though never much of a

player except as a putter), which continued to the last, playing at St

Andrews, Montrose and Musselburgh." This is how he alludes to himself:-

"That little man that's seated

on the ground

In red, must be Carnegie, I'll be bound.

A most conceited dog, not slow to go it

At golf, or anything a sort of poet."

"Though reduced to a

comparatively small income, he enjoyed life till near the end, living much

with his friends, Ross of Rossie, the late Lord Saltoun, and many others by

whom he was much appreciated." He died at Montrose in 1843, when his young

friend, Tom Morris, would be a little over twenty years of age. The year

before he died his poems were published at Edinburgh by Blackwood & Sons,

1842, small 8vo. The volume was entitled, "Golfiana: or Niceties connected

with the Game of Golf. Dedicated with respect to the members of all golfing

clubs, and to those of St Andrews and North Berwick in particular."

This is how Carnegie writes of his beloved St Andrews:

"ADIEU TO ST ANDREWS

"St Andrews! they say that thy glories are gone,

That thy streets are deserted, thy castles o'erthrown;

If thy glories be gone, they are only, me thinks,

As it were, by enchantment, transferr'd to thy Links.

Though thy streets be not, as of yore, full of prelates,

Of abbots and monks, and of hot-headed zealots,

Let none judge us rashly, or blame us as scoffers,

When we say that instead there are Links full of Golfers,

With more of good heart and good feeling among them

Than the abbots, the monks, and the zealots who sung them;

We have red coats and bonnets, we've putters and clubs;

The green has its bunkers, its hazards, and rubs;

At the long hole anon we have biscuits and beer,

And the Hebes who sell it give zest to the cheer;

If this makes not up for the pomp and the splendour

Of mitres, and murders, and mass we'll surrender;

If Golfers and caddies be not better neighbours

Than abbots and soldiers, with crosses and sabres,

Let such fancies remain with the fool who so thinks,

While we toast old St Andrews, its Golfers, and Links."

These four, then, Clan Ranald,

Saddell, Baird, and Carnegie, were great golfing pals, in days before that

word was in vogue, and young Tom Morris often played with them in singles

and foursomes. But Tom was probably too young and too little known to fame

as yet to appear in these matches that were recorded in verse, as, e.g.,

their famous foursome:

"Suppose we play a match: if

all agree,

Let Clan and Saddell tackle Baird and me.

Reader, attend and learn to play at Golf;

The Lord of Saddell and myself strike off!

He strikes, he's in the ditch, this hole is ours;

Bang goes my ball, it's bunker'd, by the pow'rs.

But better play succeeds, these blunders past,

And in six strokes the hole is halved at last.

Now for the second. And here Baird and Clan

In turn must prove which is the better man;

Sir David swipes sublime! into the quarry!

Whiz goes the chief a sneezer, by old Harry!

'Now lift the stones, but do not touch the ball,

The hole is lost if it but move at all;

Well play'd, my cock! you could not have done more;

Tis bad, but still we may get home at lour.'

Now, near the hole, Sir David plays the odds;

Clan plays the like and wins it, by the gods!

'A most disgusting stall; well, come away,

They're one ahead, but we have lour to play.

We'll win it yet, if I can cross the ditch;

They're over, smack! come, there's another "sich."

Baird plays a trump we hole at three - they stare

And miss their putt, so now the match is square.

In this next hole the turf is most uneven;

We play like tailors only in at seven,

And they at six; m<>>t miserable play!

But let them laugh who win. . . .

We start again, and in this dangerous hole

Full many a stroke is played with heart and soul:

'Give me the iron!' either party cries.

As in the quarry, track, or sand he lies.

We reach the green at last, at even strokes;

Some caddie chatters, that the chief provokes,

And makes him miss his putt; Baird holes the ball;

Thus with but one to play, 'tis even all.

Tis strange, and yet there cannot be a doubt,

That such a snob should put a chieftain out;

The noble lion thus in all his pride

Stung by the gadfly roars and starts aside;

Clan did nut roar he never makes a noise,

But said, 'They're very troublesome, these boys.'

His partner muttered something not so civil,

Particularly 'scoundrels,' 'at the devil.'

Now Baird and Clan in turn strike off and play

Two strokes, the best that have been seen to-day.

His spoon next Saddell takes, and plays a trump

Mine should have been as good but for a bump

That turn'd it off. Baird plays the odds it's all

But in! at live yards, good, Clan holes the ball!

My partner, self and song all three are done!

We lose the match and all the bets thereon'"

In such charming company as

Mr Carnegie, Sir David Baird, Clan Ranald, and Saddell, would Tom play many

matches and listen to stories of many more in those far-off days. |