|

1814-1825.

THE pack just referred to was

the Lothian, now the Duke of Buccleuch's, the master Mr Robert Baird of

Newbyth, grandfather of the present Sir David Baird, and the huntsman Will

Williamson.

The Lothian Hunt had been

established about the year 1783 by Henry, third Duke of Buccleuch, Mr Baird,

Colonel Hamilton of Pentcait]and, and other gentlemen. The country consisted

of the greater part of Mid and East Lothian, which was hunted from kennels

at Dalkeith park, and Part of Berwickshire, known as the Duns country, which

appears to have been overtaken from kennels at Langton." In 1826, Mr Baillie

of Mellerstain, who, up to that year, had hunted the remainder of

Berwickshire along with the counties of Roxburgh and Selkirk and a large

part of Northumberland, broke up his establishment and handed over his

country to Mr Baird ; while in the following year, Walter, fifth Duke of

Buccleuch, whose guardians during his minority had subscribed largely on his

behalf to the maintenance of the pack, attained majority and agreed to join

Mr Baird, then the only surviving original subscriber, in the mastership

—the arrangement being that upon Mr Baird's retirement, the hounds, the

horses and everything connected with the establishment should become the

sole property of the Duke. Accordingly on Mr Baird's retirement or death—he

did not long survive the making of the arrangement—the pack became the

property of the Duke, and has ever since been known as the Duke of

Buccleuch's. And it is an interesting fact that the old Lothian blood still

exists, and that there are in the Linlithgow and Stirlingshire kennel

to-day, partly through Darling (1895), by The. Duke of Buccleuch's Trident

(1892), and partly through a draft got from his Grace in 1907, descendants

of hounds which were in the pack in Mr Baird's time, and which, nearly a

century ago, must have crossed the old grass of Linlithgowshire with Will

Williamson. Shortly

after the Linlithgow and Stirlingshire establishment was broken up in 1814,

Mr Baird asked Granger to become his huntsman in place of Collison, who had

resigned ; but Granger declined, and it would seem that his term of hunt

service with the Linlithgow and Stirlingshire pack was his only one.

Retiring into private life, he died in the year 1846, at the age of

eighty-one, and was buried at North Newbald, near Beverley, in Yorkshire. In

declining Mr Baird's offer, Granger suggested the promotion of Williamson

who had been whipper-in under Collison. This suggestion Mr Baird acted upon

in the year 1816, and if Williamson did not actually begin his first season

as huntsman, in Linlithgowshire, it must have been very shortly after its

commencement that he brought his hounds to the kennels at Winchburgh, for it

is recorded that the first fox he ever killed was one from a fixture at

Armadale toll-bar, a little to the west of Bath- gate, hounds pulling him

down after seven or eight miles before he could reach Callendar woods, near

Falkirk. Few packs,

probably, had a greater range of country than the Lothian-under the

management of the late worthy and lamented Mr Baird —enjoyed at this

period,—its strict limits extending from the Duke's coverts3 west of

Linlithgow, to Penmanshiel wood, beyond Cockburnspath, on the road to

Berwick—a distance of nearly sixty miles by the milestones—and embracing,

with a small part of Berwickshire, the whole of the three Lothians—or in

other words, the entire counties of Haddington, Linlithgow, and Edinburgh.

Of each of these I shall now proceed briefly to speak; and commence with

that of Linlithgow, which, as a hunting country, was decidedly in every

respect to be preferred to the others. In the first place it held a

remarkably good scent at all seasons of the year, and consisted, for a

provincial, of a very fair proportion of grass; secondly, it was a flat and

very pleasant and straight - forward one to ride over; and thirdly, the

foxes were flyers, and the coverts, the majority of them at least, were

neither too large, nor crammed with that redundance of game that is so

destructive and inimical to sport in the largest portions of Mid and East

Lothian. I cannot, indeed, imagine, and certainly have never seen, anything

much superior to the cream of it; and it was here that this splendid pack,

with Williamson at their head, displayed themselves in their proper colours.

It was indeed a delight, after witnessing the distressing and fruitless

efforts of man and hound in the cold cheerless ploughs they usually came

last from, to see twenty couples of these magnificent animals pressing their

fox gallantly away from Binnycraig, Drumshorelane moor, Duntarvie, or

Riccarton, and afterwards sticking to him over a country that permitted them

to do so without the continual interruption of glens, bogs, hills, and

pheasant preserves, which, with sown grass and young wheat, were elsewhere,

in the rare event of a run, such vexatious and almost insurmountable draw -

backs. It was only twice a year, however—November and the end of March—that

the arrangements of the Hunt could allow this comparative Leicestershire to

be visited, and then only for a fortnight at a time; but I think I am not

going too far in saying, that in one of these brief periods there was

generally more sport than in six weeks' hunting in either of the other

counties. The kennel at Winchburgh, which the hounds during these occasions

occupied, was, without exception, the very worst and most inconvenient I

ever beheld; but this could neither prevent their being turned out in their

usual most superior form, nor detract very materially from the pleasure with

which their huntsman always looked forward to the fortnight in the west

country.' Nor indeed was it to be wondered at that he did so; for in the

words of Colonel Cook, when speaking of the late Lord Vernon's huntsman, Sam

Lawley, in the Bosworth country, he had nothing to do but ride as fast as he

could—it was all racing heads up and sterns down;' and the contrast between

this and the unsatisfactory toil imposed on him in the neighbourhood of

Newbattle, Dalhousie, &c., must no doubt--especially to a man so completely

wrapt up in the sport of his pack—have been either delightful or miserable,

according to the direction in which his hounds were travelling. . . .

Nothing could be much stronger than Williamson's attachment to West Lothian

for the sake of his hounds. So fond indeed was he of it, that he would never

allow the possibility of its being taken away from them, by the

re-establishment of the old Linlithgow and Stirlingshire Hunt; which event,

however, in despite of his hopes and predictions took place . . . at the

beginning of 1825."

These brief sojourns of the Lothian Hounds in the Linlithgow and

Stirlingshire country must have been looked forward to with no little

pleasure by those of its residents who still cared to hunt and had at their

command the means of following the chase. "Angels' visits," they might be

termed in consequence of their having been so few and far between, and

doubtless as such they were looked upon, and appreciated accordingly. During

them it would seem that much brilliant sport was enjoyed, and in particular,

in the spring of the year 1821, hounds appear to have had an unbroken

succession of most capital plus. In the spring of 1823, when again there was

brilliant sport, a curious incident occurred during a burst from Kinneil

wood. As a, member of the field was riding over some ground covered with

stunted gorse, he and his horse almost suddenly disappeared; the horse sank

into the bowels of the earth, but his rider, being providentially thrown

over his head, escaped by catching hold of some weeds. Ropes were

immediately procured, and a descent was made, in order to explore the

cavity, which was found to be eighteen feet perpendicular, and afterwards to

extend to the depth of nearly seventy feet in a slanting direction, at the

bottom of which the horse was found, alive. The country people instantly

volunteered their services, and the entrance to the pit, caused by the

falling of the metals in a stratum of coal, being enlarged, the horse, after

eight or nine hours' labour, was brought to the surface unhurt, and

travelled eighteen miles the next day.

Mr Baird has been alluded to as "a sportsman of

renown," and in this he has probably not been rated too highly. "Mr Baird is

a veteran of the old school, and, as a thorough-bred sportsman, and

gentleman, is a universal favourite in this part of the world. He is upwards

of sixty, and yet, among all the young bloods of the Lothian Hunt, you will

see few neater turns-out than Mr Baird on his mare Bounty." But under his

rule the whole establishment was well turned out, and it would seem that no

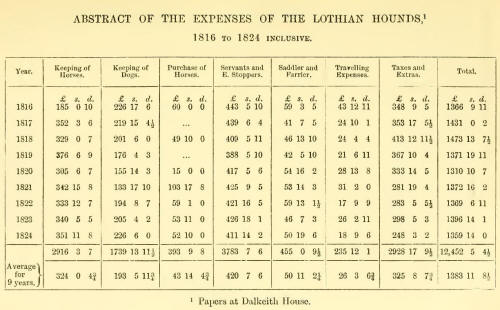

expense was spared, for the statement on the following page shows that

between the years 1815 and 1825, the period during which Linlithgowshire was

visited, the annual cost was never less than £1300 per annum, while, in

1818, it amounted more nearly to £1500—the hounds hunting three and four

days a-week.

Williamson, who afterwards became such a prominent figure in the annals of

Scottish hunting, was born in August 1782. His father, James Williamson,

after having acted as whipper-in to the Lothian Hounds under Mr Baird and

Colonel Hamilton, became head - groom to the latter, and it was then that

Williamson entered the Colonel's service as message-boy. In 1802 he began

his hunting life as second whipper-in to the pack with which his father had

previously been connected. Seven years later he was promoted, and after

serving as first whipper-in for another period of seven years, was made

huntsman. This position he held, first under Mr Baird, and afterwards under

the Duke of Buccleuch, for the long space of fort-six seasons, his

retirement not taking place until the end of the month of April 1862. "Mr

William Williamson, the oldest living huntsman, bar Toni Wingfield, senior,

has retired from the Duke of Buccleuch's service. This celebrated Scottish

worthy was born in 1782, just one year after the late Lord Campbell, and

those who were at the last Hartrigge meet, at which his Lordship was

present, remember how the Lord Chancellor came out to greet Will on the

lawn, and how the great Scottish huntsman thanked the great lawyer from his

saddle, for the honour he had done their mutual country by his occupation of

the English woolsack. Unluckily, no photographer was by to 'fix' that

memorable handshake between 'Plain Jock' and Will. Will's professional

hunting sphere has known no change, although for twenty or thirty years he

occasionally had a mount from his Meltonian pupils, to see a gallop with the

Quorn. At thirteen he went to serve under his father, who was then groom to

Colonel Hamilton, and stayed there seven years as message-boy and pad-groom

to the Colonel ; and in 1802 he commenced his sixty years of hunting life as

second whip to the Lothian Hounds, of which Mr Baird, of Newbyth, was the

master, John King the huntsman, and Frank Collison, father of Peter of the

Cheshire, first whip. In seven years' time Frank got the horn, and after

keeping it for seven more, retired in Williamson's favour. Will thus got his

promotion eleven years before the present Duke of Buccleuch came of age, up

to which time 'The Lothian' was a subscription pack, and held it till April

22nd of this year, when he hung up his coat and cap after as long and as

honourable a service, and under as good a master as ever fell to huntsman's

lot."

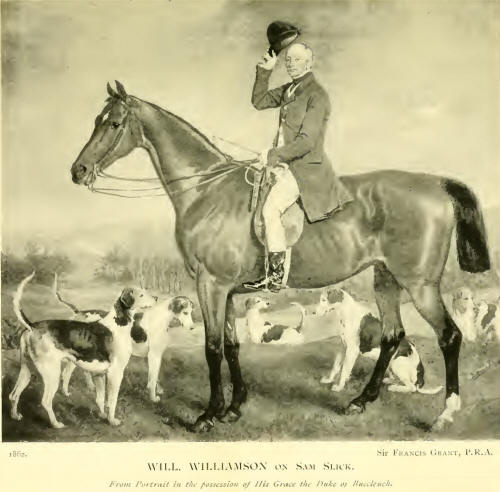

No portrait of Williamson was

painted until after he had retired, but he then sat first for Sir Francis

Grant and afterwards for Mr Frain. Nimrod, however, sketches him as he was

in the autumn of 1834, when about fifty-two years of age.

The stature of' Williamson is below the average

height of man, but his person is well turned and very well proportioned; and

the exact fit of his clothes sets it off to advantage. The sit of his cap,

the fall of his shoulders, and the junction of the breeches with the boots—a

great point in a horse-man, as far as the eye is concerned—are all equally

good; and the general cleanliness of his person, renders the tout ensemble

complete. He has a keen, penetrating eye; carries his country in his face,

as well as its full dialect on his tongue; is, as Lord Kintore says of him,

'an astonishing bit of wire— a sort of' genus per se- and the king of'

Scotch servants.' " The

portrait by Sir Francis Grant was painted for the Duke of Buccleuch, and

some of the letters 2 which Sir Francis wrote to the Duke, at the time, are

both interesting and amusing. The first of' these mentions Will in the

studio, getting rather weary of' 'sitting,' but instantly enlivened by the

arrival of a letter from the Duke.

27 SUSSEX PLACE, REGENT'S PARE, N.W.,

25th Oct. [1862]. MY

DEAR DUKE,— . . Your letter was brought into the painting room whilst Will

was in the act of sitting, and was getting rather tired. But the arrival of

a letter from you, put him all alive. I showed him a portion of it where you

speak of my knowledge of his character and peculiarities—Will read it

"propensities." "Ma propensities, what can his Grace mean by ma

propensities," and then he went into roars. I have only, since Will left,

discovered that the word is peculiarities.

I am, I hope, getting on well with him. I think

Will seems much satisfied. He says "Noo I dinna want you to mak me just as I

am, but what I used to be, for, for some years back, I have only just been

an apology for a Huntsman."-1 am, ever my dear Duke, yours very truly and

obliged, FRAN. GRANT.

The next letter refers to the termination of the "sittings," and to the

introduction into the picture of some of the hounds as well as the horse

"Sam Slick." It also refers to Will's deafness,

27 SUSSEX PLACE, REGENT'S PARK, N.W.,

Nov. 2 [1862]. MY DEAR

DUKE,—YOU will be glad to hear I am done with Will, and I think it is very

successful. He seemed much pleased himself. I have arranged with him to have

some hounds up to Melton the first good frost, when they can be spared. He

talks of' coining with them himself—lie is so much interested in the

picture. He was very

amusing—h is anecdotes numerous. When he left me, I always got a cab to the

door for him, when he invariably roared out to the cabman, "Do ye ken a

place caa'ed 'Belgrave Square.'" When the cabman assented, and succeeded in

making Will hear, lie said, "Wed, I want to be taken to a hoose there, No.

thirtyseeven."—I am ever, my dear Duke, yours truly,

F. GRANT. P.S.—This

letter needs no answer, but I thought you would be glad to hear that we

think we have been successful, he is very anxious that the likeness of Sam

Stick may be attended to.

The last letter of interest mentions the

completion of the picture and arrangements for its despatch to Dalkeith.

27 SUSSEX PLACE, REGENT'S PARK, N.W.,

Aug. 23 [1863]. MY DEAR

DUKE,—The picture will leave my house for Dalkeith on the 1st September. 1

only quite completed it yesterday. To-morrow or the day after, I must give

it a slight varnish, and it will require all the week to be thoroughly dry.

The carver and guilder has orders to call for it on Monday the 31st and send

it by rail to Dalkeith on the 1st of September.

I am much obliged for your kind message. I

assure you I painted the picture con amore, and I hope it is a good memorial

of poor old Will. I wish I had painted the horse from nature. But Will was

so urgent—"I maun hae my horse SanL Slick," that I had no option, and on the

whole it is best that it should be a brown animal.

I am ever, my dear Duke, yours very truly, F.

GRANT. Amongst these

letters there is one from Williamson to the Duke which, besides indicating

his Grace's constant kindly attitude towards Will, expresses the latter's

unswerving regard for his master.

ST BOSWELLS, 10 Nov. [1862].

MAY IT PLEASE YOUR GRACE,—I beg to say it is

with a feeling overcome by more than I can express (having received from Mr

Sutherland a note intimating your Grace's never failing consideration and

kindness) that I attempt to address you, so far short of what my mind, under

a less impressed state, would have enabled me to do.

However, I beg to assure your Grace it is with

the sincerest gratitude that I conjure up all the benefits I have received

from you, but as the case is without a parallel between master and servant,

it masters me to enter upon it, and I can only conclude, your Grace, by

re-iterating what has been a thousand times my standing toast—viz.. "The

Duke, God bless him."—And I am, may it please your Grace, your most humble

servant,

W. WILLIAMSON

Williamson did not live many years after his portrait was painted, and dying

on the 11th of February 1870, in his eighty-eighth year, he was buried in

the quiet churchyard of Pencaitland in the district in which he had passed

many of his early days.

Perhaps the subject of Williamson has been

lingered over unduly, but it should be borne in mind that, there having been

no Linlithgow and Stirlingshire huntsman at this period (1814-1825),

Williamson virtually stood in that relation to the country, or at least to

the county of Linlithgow, and that therefore some account of him and of' his

career is far from being out of place in these pages. And it is worthy of

mention that when the Lothian Hounds ceased to visit the country, in

consequence of' the revival of the Linlithgow and Stirlingshire pack in

1825, he received from those who had taken part in the sport he had shown in

West Lothian a token of regard in the shape of a silver jug which is still

preserved and cherished by his descendants. The following letter and verses

by the late Professor James Miller,' however, will form a fitting conclusion

to what has been said in regard to this famous Scottish huntsman:-

DEAR WILLIAMSON,—T have been so infernally busy

with the getting up of a dinner to your friend Mr (where by the bye, I

expected to have seen you) that I have not had time to redeem my pledge

anent my promise to send you the accompanying palaver. But coming home,

to-day, I found that you had been here, and not looking very well pleased.

So I hasten to say peccavi and make amends. Here it is in all its

imperfections. If it can help to convince you that nothing can he nearer my

warmest wish than to further in any way in my power your wishes or

interests, I am amply repaid for the pains of delivery that authors are

subjected to.—Ever yours faithfully,

JAS.'MILLER. "WILL O'

THE WISP."

(Air—" The Boys of Kilkenny.")

Oh long may Will stick to his "Pension and

Place,"

For tho' nearly three-score—still "full score" is his pace.

He can ride like the Devil—talk or write like the Fraist;

And he's aisy and kind both to man and to Baist.

Oh in troth he's a broth of a boy to be sure.

Tho' he doats on his pack, he's no pedlar or

cheat,

For no wares does he sport but "ware grass" or " ware wheat."

Good covers he covets, but throws cT all disguise

All that's hollow in him are his View hollo cries.

Oh in troth, &c. As a

Huntsman, who's like him, for head and for heel,

As sharp as a razor, true and hard as the steel

With both science and bottom, pluck, talent, and fun,

And the rank of full major—being now twenty-one.

Oh in troth, &c. As a

man and a friend he is "warranted sound,"

If a better you'd seek, let it be underground.

Staunch, sterling, and steady,—tough, trusty, and true,

He's beloved and respected by Noble Buccleuch.

Oh in troth, &c. For

title and rank due respect he maintains

In return their esteem, and their friendship obtains.

All follow him hard over turf, hill, and heath,

And none stick so close as the gallant .Newbyth.

Oh in troth, &c. More

power to his elbow More success then to Will!

May he equal Saint Patrick in the varmint he'll kill,

Hounds healthy and fleet,—horse and men fast and sound

And long may it be before lie's "run to ground."

For in troth, &c. "THE

DUSTY MILLER." While

the Lothian Hounds, under Mr Baird, were periodically hunting the

Linlithgowshire side of the country, during the interregnum, the R. A. L. D.

S. Hounds, under Captain, afterwards Sir, David Baird, Mr Baird's son,

visited the Stirling- shire district occasionally, and, judging from the

following account of what appears to have been a long and fine run, the

confines of West Lothian also. This Hunt was so styled from the initial

letters of the counties hunted by it, namely Renfrew, Ayr, Lanark, Dumbarton

or Dumfries,— probably the former—and Stirling. The hounds had three

kennels, one of which was situated at the mouth of the Doon in Ayrshire,

another at Cathcart near Glasgow, and the third at Motherwell. Captain Baird

had undertaken the management of the pack in the year 1822, but after acting

as master for two seasons, retired in favour of Mr James Oswald of

Shieldhall, who in turn gave place to Lord Kelburne in 1826. When Captain

Baird took the hounds, it would seem that they were not in the best possible

form, but through the care and attention which he bestowed on them during

his mastership, a great improvement was effected.1 This is borne out by the

account of the run already referred to.

"On Saturday, the 10th April [1824], Captain

Baird's Hounds had a fine day's sport. The place of meeting was Armadale

toll-bar, on the Glasgow road, where they immediately found a fine fox, with

which they went away at a killing pace, towards the village of Bathgate,

upon nearing which, he turned to the left, through Mr Marjoribanks, of

Marjoribanks, grounds, for Wallhouse craig, where being headed, he gallantly

faced the Bathgate hills, and skirting the numerous lime quarries, disdained

all the earths. Here he turned short to the left, and crossing Hilderston

hill, he ran through Witch-craig wood, the west parks of B'ormie, and

continuing in a north direction as far as the bottom of Cockleroi, he turned

to the right, and running over the fine grass country of B'orrnie, he never

varied a point till he reached Riccarton wood," where he was so closely

pressed by the gallant pack, that he was obliged once more to take the open

country. He broke away toward the Binny craig, but leaving it to his right,

he made for the badger earth S2 where he was twice viewed, dead beat, and

here he would have been killed, had the scent at all served on the ploughed

land. Getting away again, he crossed the Linlithgow road, ran through the

Champfleurie grounds as far as the Union canal; here he turned round and

came back to Champfleurie, where he went to ground in a drain at the bottom

of the garden,—thus completing one of the finest runs ever seen with

hounds,—the extent of the country, point-blank, not being less then 14

miles, and, taking the run, certainly not less than 20 miles. Never did

hounds do their duty better: it was a fine finish to the season. Too much

praise cannot be given to Captain Baird for' having in so short a time

brought his hounds to so high a state of perfection."

Although the Lothian and R.A.L.D.S. packs had to

some extent filled the place of the Linlithgow and Stirlingshire during the

seasons which followed the sale of the hounds in 1814, there had evidently

existed in the country, throughout this period, a feeling of regret that the

old Hunt had died down, and a sort of smouldering desire for its revival,

requiring but little to kindle it into life. How the embers of this desire,

which, having been stirred and fanned into a glow by the good sport shown in

the visits of the above-mentioned packs, suddenly leaped into flame with the

coming of the new year of 185, will be described in the pages which

immediately follow. |