|

We have arrived now at

the fourth stage .in our descent in the social scale, passing the poor

man as he-is found at home, in furnished lodgings, and in common

lodging-houses, till we come to the habitual rover, who calls no place

his home, who belongs to no particular town, county, or country, but is

for ever on the move ; wandering, he cares not whither and knows not

why.

Adopting a famous

phraseology, it may be said that some are born tramps, some drift into

tramp-life, and some have tramp-life thrust upon them. The

first-mentioned class are those who have been born “ on the road,” the

children of tramps, reared in the profession, and remaining in it all

their lives. There is such a thing as hereditary tramphood; the tendency

to rove seems to run in the blood like physical or mental traits; with

this difference, that the wandering propensity does not jump one

generation and reappear in the next, as inherited idiosyncracies

commonly do.

We know of at least one

noted tramp, whose father and grandfather were tramps before him, and

who, at the present moment, is bringing up a large and promising family

to his ancestral vocation.

Those who have tramp-life

thrust upon them are not, we believe, a large section of the

brother-liood, for the act of entering the calling is almost always more

or less voluntary. Yet it frequently happens that a man may be dragged

into the life against his will.

For example, a man living

with his wife and family in Edinburgh, finds himself suddenly thrown out

of employment. Unable to obtain work here, he sets off for Glasgow on

foot. There he finds something to do, in a few weeks sends for his

family, and they, selling off their modest furniture, join the

bread-winner in Glasgow. But soon lie is again without work, and this

time he migrates to Dundee, perhaps, whither the family follow him at

the earliest possible day. A few moves of this kind soon begin to tell

upon the habits of a household. The mother and the children, left behind

while the father is looking for work in another city, become initiated

into the mysteries of the begging business ; domestic stability rapidly

goes; and in the course of time the family are enlisted in the ragged

regiment that are constantly parading every highway in the country. Once

they adopt that career they very, very seldom forsake it. Life then is

but a slouch onward to the poor house, or until they lie down to die

behind a hedge.

But the genuine,

thoroughbred tramp—he who may be said to have of his own will adopted

the profession—is a shiftless, lazy rascal whose chief aim is to get

through life with the least possible amount of labour. His aversion to

work might be said to amount almost to a passion, were it not that he is

too easy-going to harbour such a strong feeling. His disinclination to

exertion takes rather the form of a placid determination not to be moved

from the passive attitude he has assumed with respect to the industrial

system. To this line of conduct he adheres with a persistency quite

pathetic in its steadfastness.

There is a story told of

two tramps that deserves to be true if it is not. They had fallen asleep

in a cosy corner in an out-house and were snoring as loudly as if they

had earned their repose, when one of them began to stir uneasily and to

give vent to half-stifled moans. These symptoms of dispeace increased

until he awoke with a shriek, and trembling violently. “What’s the

matter?” anxiously inquired his companion who had been roused by the

commotion. “Oh, something awful,” groaned the man with the nightmare, as

he buried his face in his hands. “I’ve had a terrible dream. I dreamt I

was workmy!” Only a tramp could appreciate the horror of a vision like

that.

Circumstances, however,

arc sometimes more than a match for the tramp, so that he finds himself

reduced to the absolute necessity of throwing off his coat and expending

some of his precious energy. And this leads us to note that, broadly

speaking, tramps may be classified for the sake of convenience into

“working” and “nonworking.” .

The “working” tramp is a

man (or woman) who wanders about the country “in search of work,” as he

puts it when making his piteous appeal to charitable persons and

societies. He works for a day or two or a week or two in a town, then

off he goes to some other place. The demon of unrest seems to possess

him. He cannot remain long in one place; he has not sufficient fixity of

purpose for that. “Give a tramp the best job in Scotland, and, ten to

one, he won’t stop at it,” said a man to us who had himself been in the

profession, but had had the rare good fortune to be weaned from it. You

may get him to work steadily for a little while, but just as you are

beginning to believe in his reformation, he becomes restless and

dissatisfied, drinks any savings he may have made, and breaks loose once

more.

One of the worst

instances we have known of temporary reform followed by complete relapse

was that of a tramp who, coming under powerful influence, settled down

to sobriety and the business of a fish hawker. Being a smart fellow, he

prospered, and in the course of three years bought a horse and cart, and

saved £133. But one unfortunate night he broke his pledge, and “got on

the spin.” It seemed as if a devil had taken possession of him. Nothing

could stop his mad career. In ten months he drank the £133 lie had in

the bank, and his horse and cart, in addition to the money he earned in

sober intervals during that time. Thus reduced to his former poverty he

took to the road again, and is a more confirmed tramp than before. As

well try to harpoon the wind as attempt to fix these rovers to any

permanent employment.

These tramps of

intermittent industry are to be met with in great numbers on the roads

leading to large commercial centres. From Glasgow to Dundee is their

favourite route, thence through the small but busy manufacturing towns

of Fife to Edinburgh, from which they slowly make their way back again

to Glasgow. Many spend almost their entire lives on this tour, tramping

and working, and working and tramping, doing the round over and over

again, with an occasional excursion, perhaps, to Newcastle or Carlisle,

or some other distant part. But wherever they go, it is with the same

aimlessness, and productive of as little abiding benefit.

Even a more hopeless

subject to deal with is the anon-working” tramp, who resembles his

spasmodic relation in everything except that he is not “in search of

work.” On the contrary, if he had the faintest suspicion that work was

in search of him he would run till he dropped to escape from it. People

of this class are simply itinerant beggars who rove at large over the

country, wandering wherever they think they are likely to get the most

with the least trouble. Many of them have not done a day’s work for

years, but by begging, singing, or playing a whistle in the streets of

the towns and villages they pass through, they contrive to make a

tolerable livelihood. These mendicants do not confine their tramping to

the highways connecting commercial towns, as their “ working ” brethren

do, but ramble all over the country, scouring agricultural as well as

manufacturing districts. Indeed, it is said that they fare better among

country folks than with the sharper town-bred people.

A tattered and battered

fellow whom wc got into conversation with some time ago, belonged to

this class of tramps. He was one of those cool, brazen-faced individuals

who could stare a sheriff-officer out of countenance; one of those calm,

self-satisfied persons who are never disconcerted and never in a hurry.

“I have been a fortnight

in Edinburgh,” he said. “Have been in it often before. It is a capital

place for resting my feet, and I generally stay in it a fortnight at a

time, for there arc any amount of ‘skippers’ [places for passing the

night in] all round about. I get as good a living as if I was working.

By a little mouching I can get as much grub as I need, and I can rest

myself whenever I like. But a man would be better off if he could fiddle

or whistle or do anything of that kind. I made the price of my ‘doss’

[bed] with a tin whistle yesterday on the High Street and Bank Street ;

made sixpence in ten minutes, and that got doss, tea, and sugar. I do

work occasionally to give myself a fresh start. I have been in two or

three regiments and deserted. In the winter, when 1 was hard up, I gave

myself up, but soon deserted again, and set off on the road in a fresh

rig. I was a militiaman for four years, and that kept me from settling

down, having to leave my work every year to go up for training. I have

been on tour for two years ; during winter get into skippers; in

summer-time travel through the night and sleep anywhere during the day,

under a hedge or on the roadside, only occasionally getting a bed by

singing ‘The Highlandman’s Toaro’ and ‘Flora Macdonald's Lament.’

I have got many a copper by singing them during the past six years. I

learned them from a song-book. I am quite happy and contented with my

lot. I could do like other folk, but don’t care to work.”

Another happy-go-lucky

bird of passage, during one of his periodical visits to “ this paradise

of tramps,” as Edinburgh has been called, explained his mode of travel

to us; and his account we shall reproduce, omitting, of course, the

tramp jargon, which would be unintelligible to most people.

“Say, now, that I left

Glasgow, bound for Dundee. Well, the first day I would try to get as far

as Stirling, for there is a good night-shelter there. The next day would

be an easy one, only a six mile walk to Dunblane, where there is a kind

inspector of poor who often gives us the price of our lodging. The next

night would see me at Auchterarder, where I would find a sleeping-place

of some kind; and on the fourth day I would reach Perth. Though that is

a good-sized town, it has not got a shelter, but there are lots of cosy

dosses to be got in the farmhouses round about. The fifth night I would

sleep at Errol, where I would probably get my bed from the inspector of

the poor; and on the sixth day I would reach Dundee. There, of course, I

would put up at the night-shelter. The next morning I would perhaps look

for work, or sing in the streets, or beg, and if I got any money, pass

the night in a lodging-house. But if I got no money, I would sleep in

the most comfortable corner I could find.”

This is a specimen tour;

all tramps’ excursions are managed on the same general principles.

When a tramp shuffles

into Edinburgh, from whatever point of the compass he comes, he usually

makes his way at night to the Night Asylum in Old Fishmarket Close,

adjoining the Police Office. There he takes his place among a waiting

crew of poor wretches, who, like himself, are without place to lay their

head.

About eight o’clock the

applicants for a night’s shelter are gathered together in the hall of

the asylum, and one by one, arc brought before the superintendent, who

asks them their name, age, occupation, when and where they last worked

and where they are going, and some other personal details. The rule of

the establishment is that none but strangers are admitted, and not more

than once in three months. The superintendent, however, has power to

relax the regulations in social cases, and frequently considerable pains

are taken to give assistance to persons of whose good character

assurances have been obtained. It is impossible in the nature of things

to guard , against imposition altogether; consequently, it is to be

feared that many lazy, skulking fellows get better treatment than they

deserve.

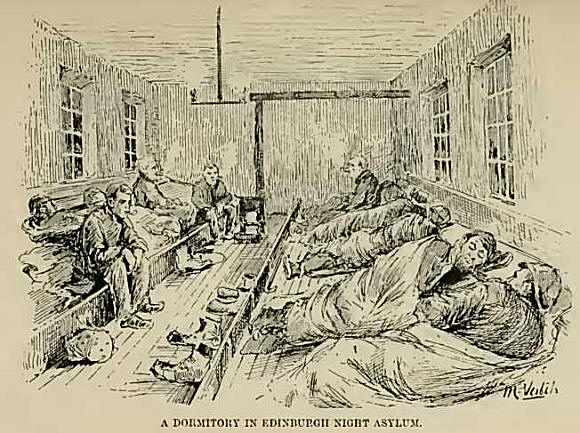

Be that as it may, when

all the applicants have passed through the catechism, and got back to

their seats in the hall, where they sit a silent, dirty, ragged company,

a supper of porridge and milk is handed round in tin basins. For a few

minutes nothing is heard but the scraping of the spoons on the bowls as

the hungry outcasts put themselves outside the porridge with amazing

rapidity. Then they all flock upstairs to the dormitories. These arc not

sumptuous apartments, but they are warm, comfortable, and scrupulously

clean. Down both sides of a long room sloping platforms arc raised about

a foot from the floor, and on these, wrapped in a rug. the homeless

creatures sleep. A stove in the middle of the room keeps the temperature

agree able. Smoking is forbidden, but it is difficult prevent men having

a whiff during the night, an possibly, the tobacco fumes may act as a

disinfectant, which, it need scarcely be said, is powerful argument in

favour of permitting the practice. In the morning the lodgers get

breakfast, and are then allowed to shift for themselves. Our friend the

tramp will probably “mouch about the city during the day, and if when

nigh draws near, he has not enough money to get f bed in a

lodging-house, he will trudge down to Leith and creep on board a

coal-boat, or a tug, or lie will leave the town and make for the nearest

pithead, brickwork, coke-ovens, farmhouse, or, in fact, any place where

he can find a warm shelter. He delights to coil himself up in a

boiler-house or beside a glowing ash-heap. Not unfrequently, poor

fellow, he pays for this comfort with his life, for while he sleeps he

is suffocated by poisonous fumes, and in the morning his charred body is

found lying on the cinders.

It is a curious fact that

tramps seldom pass the night in stairs and such-like retreats of the

destitute in towns. It is usually street loafers and resident beggars

who do that. The true tramp prefers the open country.

A tramp’s knowledge of

the country through which his beat lies is as peculiar as it is varied,

e knows the farms where a shakedown of straw in outhouse may be counted

upon; he remembers also the steadings whose owners discount his visits

and where the watch-dogs are corruptible. Towns and villages arc mapped

it according to their relative hospitality. If lie in a communicative

mood he will tell you that Dalkeith is one of the “hungriest holes in

all Scotland ” for tramps, and that lie would give lie palm for

parsimony to the village of Cockburnspath. On the other hand the place

where tramps receive the most generous treatment is, lie thinks, in the

fishing village of Eyemouth: the reason why, he docs not know, except

that it is because fisher-folks are simple-minded, kindly people.

With such knowledge as

this at his finger-ends, a gentleman of the road can lead not an

unpleasant life in summer-time. In winter, however, he has to put up

with many hardships. But if he is a man of resource, he can usually hit

upon some plan to secure his comfort during the cold months. He may

retire gracefully to the poor-house or the hospital and lie there snug

until the -return of weather favourable to travelling. To make

themselves eligible for residence in the infirmary, tramps, resort to

all sorts of tricks, They have been known to run a knife into their hand

or to disable themselves in some other way. One man we were told of

could simulate pals so well as to defy detection by the doctors, and

another could so contort his face as to make the medical men believe

that he was in a very bad way indeed. .

Another aimiable weakness

that tramps have is that of passing themselves off as unemployed during

strikes or in times of commercial distress. Whenever a strike occurs in

any district thither the tramps flock, and for the nonce take up the

profession of the unemployed, and a very easy and paying job it is too.

There are some tramps who

save money. One we know of is roving about at this present moment 'with

£90 sewed in the lining of his coat. Another, the last time he left

Edinburgh, earned with him a bank book showing a credit balance of over

£100. But these are rare exceptions. The ordinary tramp lives from day

to day,

from hand to mouth, at

the expense of the public; and when at length lie has trudged his last

mile, and lays himself down to die in the poorhouse hospital, he makes

his last exaction upon society for the amount of his funeral expenses. |