|

We come now to a lower

circle in this. Inferno— the third. We have had glimpses of life as it

is to be seen in the one-roomed dwelling of the poor man ; we have also

looked at the conditions of existence a grade further down, where the

system of “furnished lodgings” is in vogue; our next descent is to the

sphere of the common lodging-house. The people who live in common

lodging-houses may be said to be in the very lowest strata of our

population, embracing as they do inferior artisans and labourers,

criminals of all kinds, tramps and beggars; all those pitiable beings,

in fact, who because of misfortune or bad character, have never been

able to gain an independent position in life, but drift about, like

straws in the gutter, a misery to themselves and a constant annoyance

and burden to the community.

Lodging-houses, of

course, differ in degrees of respectability. One house may be noted for

its cleanliness, orderliness, and general good management. Another may

have a bad reputation as a refuge for thieves, and women of questionable

character, and, accordingly, have the eye of the police continually upon

it. A third may be the favourite “howff” of the tramp tribe; while

resident mendicants make a fourth their customary “doss-house.”

Like their reputations,

the internal arrangements of common lodging-houses are after a variety

of patterns. In general, however, they arc planned in this simple and

comprehensive style. From the street a passage, in which there is a

pay-box like a railway booking-office, leads to the general kitchen,

where the lodgers cook and eat their food, and lounge, talk, and smoke.

Upstairs, as many flats as you please, are the bedrooms and dormitories

with the accommodation painted in large letters on the doors. These

rooms may be bedded for any number of people, from two up to forty, or

even more. Some of them arc wonderfully clean — considering the habits

of their occupants: some of them are no tidier than they should be; and

not a few arc execrably dirty.

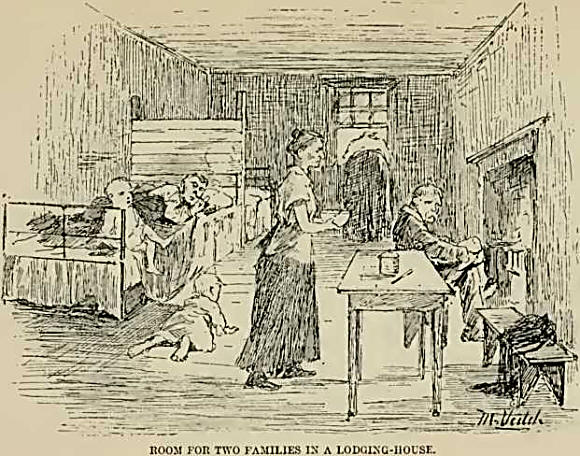

But what will strike one

as the most notable feature of the sleeping-rooms in common

lodging-houses is the scant attention paid to privacy in the married

quarters. One would expect that in houses licensed by our Magistrates

and under their direct supervision, the bed-rooms would be arranged with

more regard to the dictates of decency than is found in a Zulu kraal or

a Patagonian mud-hut. And this disregard is only emphasised by a

pretence made to preserve the “sacred secrecy” of the family. It is

quite a common thing to see one room occupied by two or three married

couples and their children. The beds are placed end to end, and are

separated only by a board the width of the bed and about the height of a

man. This partition is a mere make-believe, a nominal concession to

propriety, and does not afford the slightest seclusion to any of the

occupants of the room. The obvious pretentiousness of the arrangement

irritates one. The erection of the screen is a tacit admission that

there ought to be seclusion, but one might as well attempt to secure it

by sticking a twopenny Japanese fan between the beds as by putting up

these boards.

The lodgers themselves do

not seem to deprecate this publicity; they move about among each other

without restraint or bashfulness, each family acting as if there were no

strange eyes looking upon them. Such is the effect of habit.

"A lodging-house is no

place for a man who has a wife and bairns. Some of them are perfect

hells, and none of them are heavens,” said a man to us who had had a

long and varied experience of life in these houses. Doubtless this would

be the opinion of most people of similar experience ; yet their efforts

to escape from their baneful surroundings arc seldom attended with

success. The attempt is often made. A man and his wife will leave a

lodging-house they have lived in for some time, saying that they intend

to set up a home of their own. But the chances are that in a few weeks,

or months at the most, they are back again in their old quarters, driven

there by their old enemy, drink. “There are very few of them need be

here at all, if it were not for drink; if it was not for that, they

would have houses of their own,” a Grassmarket lodging-house keeper

remarked to 11s. “They can never gather enough money to enable them to

begin housekeeping; but if they do, they soon break out again, drink up

everything, and come back again worse off than ever. Once they become

accustomed to the lodging-house life they seldom get out of it.”

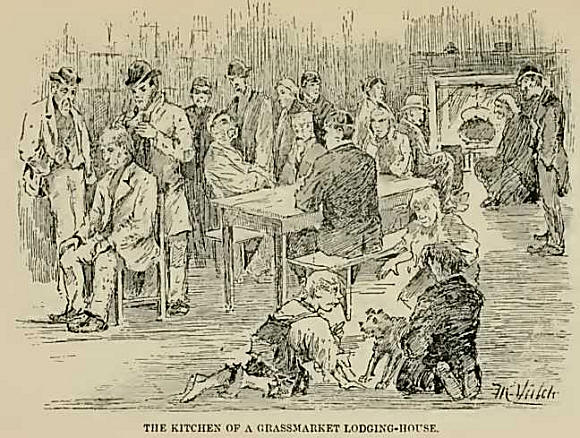

The kitchen of a

lodging-house is an exceedingly interesting place. There the picturesque

may be studied under conditions not easily found elsewhere. One kitchen

we have in our mind’s eye is representative of most of them. It was a

long, low-roofed room, with a stone floor. At one end there was a big,

old-fashioned fireplace, in which a mighty fire roared and crackled. On

a stool at a corner of the hearth sat a ragged old man toasting a red

herring of powerful odour spitted upon a stick. In front of the fire,

assiduously stirring the contents of a hanging pot, stood a nut-cracker

faced old woman, so bent, so wrinkled, and altogether so “uncanny”

looking, that one would have thought it quite in keeping with her

appearance if she had suddenly vanished up the chimney astride a

broomstick. On benches on either side of the room and around the fire

sat a score or more of the seediest, motliest beings that one could well

gather together. Women in short kirtles, with their bare arms folded or

set akimbo, were “ chaffing ” men with dirty unshaven faces, battered

hats, and garments that an old-clothesman would have nothing to say to.

Some of those dingy lodgers, men and women alike, were smoking ; some

lay asleep on benches, and some sat gazing dreamily into space. Several

unwashed children were disporting themselves with a bandylegged mongrel

dog, which seemed to be the joint possession of the whole colony. In a

corner a man of dilapidated exterior was cutting tlic hair of one of his

“pals,” an operation which drew forth facctious remarks from several of

the onlookers, their humour finding vent in speculating as to where he

got the previous “ crop ” and where lie was likely to get the next one.

It was a Sunday, and

though it was past four o’clock in the afternoon most of the men had

just risen, and were dressing by easy stages. Quite a number of the

lodgers of the house, in fact, did not leave their beds at all; for not

being addicted to the habit of church-going, and finding the Sunday

quietude of the Grassmarkct irksome, they preferred to pass the day in

slumber. Besides, as not unfrequently happens, when a man has not got

anything in the larder, he finds it easier to stifle the complainings of

an empty stomach in bed than in loafing about the streets or sniffing

viands cooking in the kitchen.

In a lodging-house each

one does his own cooking, unless a number of persons agree to cooperate

to save trouble. Every one for himself, however, is the general rule.

But, then, this sort of people don’t go in for elaborate culinary

effects. A bit of bacon fried, a roasted herring, and such easily-cooked

morsels, with a piece of bread, cheese, and tea, form their staple

bill-of-fare.

Each lodger has a small

locker, in which he stows away any property or provisions he may be

possessed of; but, as one man ruefully observed, “they’re no’ o’ much

use, for it’s no’ often that we’ve mair than the smell to lock awa’.”

The charge usually made

in common lodging-houses is 6d. a day for each individual; if a person

stays a whole week he pays only for six days, the seventh day’s lodging

being given free of charge. When, say, two or three families occupy a

room such as the one shown in the sketch, they each pay 4s. a week,

making 8s. or 12s. a week that the proprietor draws for the rent of one

room of insignificant size and wretched furnishings, which consist of

the beds, a table, and a bench or two.

In the Model

Lodging-house in the Grass-market the rates are 4d., 5d., and 6d.,

without a free day on Sunday. Its internal arrangements arc as much

superior to those of the average lodging-house as a well-regulated hotel

surpasses a low cook-shop. The building is large and airy, as clean as a

man-of-war; the bunks are neat and comfortable, the dormitories

admirably ventilated ; and in addition to a large dining hall and a

cooking range, there is a well-appointed reading room.

“Why don’t you prefer to

go to the Model Lodging-house?” we asked a dirty specimen of the tramp

tribe whom we met in one of the least washed “doss-houses” in the city.

“Well, ye see, sir,” he replied, “we havena got the freedom there that

we have here. There arc ower mony rules and regulations in the Model.

Ye’re 110 allowed to lie in your bed a’ day if ye want to, or to gang

aboot as ye like. There arc ower mony men in uniform goin’ aboot for my

taste.” In the estimation of this man, and of his kind, the lousy

freedom of the den he kennelled in was more to be desired than the

cleanliness and regularity of the Model Lodging-house.

There really is a

Bohemianism about the life in a common lodging that suits the tastes of

those restless, careless characters; and in their own way they have

jolly carousals now and again.

One Saturday night, as we

were climbing the stair to a lodging-house noted as a resort of hawkers,

beggars, and street musicians, we heard sounds of uproarious merriment

coming from the kitchen. When we entered we were confronted with a

grotesque scene. The room was filled with a hilarious company,

picturesque in their rags. In the centre of the floor, surrounded by a

laughing, joking, applauding group, were a man and a woman going hard at

an Irish jig, putting as much agility into their toes and heels as if

their reputations depended on their exertions, as no doubt they did. The

room was stiflingly hot, and the boots of the man and the woman were by

no means of dancing-shoe make, but they kept it up without faltering or

flagging for a moment. And right good dancers they were too, not merely

shuffling through with any sort of apology for figures, but whirling,

linking, and setting, all in perfect time and step. Faster and faster

scraped the fiddler, faster and faster twinkled the feet of the dancers,

and louder grew the whooping and applauding of the spectators.

At length the man gave in

and withdrew, but the woman, whose excited eye and whisky-reeking breath

betrayed the secret of her exuberance, vociferously called upon another

partner. Again the jigging began, and soon waxed as furious as ever.

However, despite the whisky and the boisterous cries of encouragement

from the onlookers, the woman’s endurance was eventually exhausted, and,

panting and perspiring, the dancers sank on to a bench. Then came a

singing interlude with violin accompaniment, at the conclusion of which

the flagstones again began to resound with the clatter of swiftly moving

feet.

That night with the jolly

beggars was a glimpse of the bright side of lodging-house life, a brief

lifting of the heavy clouds that overshadow existence there. The normal

conditions, however, are painfully sombre; they arc poverty and hunger,

filth, wretchedness and wickedness, degradation and despair. |