|

It is the impudent beggar who hustles to

the front, and carries off the

lion’s share of Charity doles. He never starves. He is too cute ever

to fall into such dire extremity. If the calamity he dreads most of all

comes upon him, and he is actually compelled to exert himself to keep

body and soul together, he knows how to do so with the minimum of

trouble and the maximum of profit to himself. With all the outs and ins

of the “moucher’s” life he is familiar, and he is unconcerned; for he

is assured that in this city of many charities his wants will not go

long unrelieved. Assistance can be got for the asking: why, therefore,

should he so far forget himself as to render unnecessary the offices of

the good Samaritans?

It is needless to say that this rascal does not

belong to the silent, suffering class. At all points he is dissimilar to

him who is known as the “deserving” poor man. The latter is honest and

clings to his independence. He is probably a labourer or in one of the lower grades of artisans. But,

notwithstanding all his endeavours, the nature of his calling is such

that he for ever lives on the borderland of destitution. His wages are

so small and his family so large that it is only by severe pinching that

both ends are able to meet. There is nothing laid by for any day; and

when a temporary slackness of trade

throws him out of employment, he and his family at once begin to feel

the grip of poverty.

Such a man is very often quite ignorant of the ways of obtaining

charitable aid. So long as he is able-bodied the Parochial Board will

not give him outdoor relief, and lie has a horror of “the House.” There

is thus nothing between him and slow starvation; and he drags through

weeks in silent hunger, parting with his furniture bit by bit, until the

tide of fortune turns, and he once again finds work to support himself

and his family. And in this manner he passes his life, in continual

oscillation between bare sufficiency and sheer starvation.

Winter is the time dreaded most by these hard-tried creatures, for

then outdoor work is uncertain. Should a slackness in trade be added to

inclement weather, then their lot is pitiable in the extreme. During the recent railway strike, for instance, the

sufferings of the labouring classes were intense. It was not the railway

men who suffered; it was those who had been employed in works dependent

on the railway for supplies. Their name was legion. In the course of the

strike we personally discovered scores of families rendered utterly

destitute by this means. One case we shall describe as a typical one.

In a wretched hovel, a mere corner of a room, we came upon a young

man, with his wife and two infants. Their appearance and scant

surroundings indicated only too clearly abject poverty. When we entered,

the man was in bed; on the coverlet sat one of the children crying in

a faint, weary voice; and the woman, pale, thin, and wan, sat over the

tireless hearth, “crooning” the other infant to sleep. The scene was

one of dull, settled despair. This desolation notwithstanding, the faces

and the bearing of the young couple bore the unmistakable stamp of

respectability. They were not of the coarse, brutal mould in which their squalid neighbours were cast; and, unlike them, they were not ready to

pour forth the tale of their sufferings. But questioning brought out a

pitiable tale.

Till the time of the strike they hail lived in a small but

comfortable house of two rooms in a comparatively respectable locality.

But the strike threw the man idle, and in a little more than a week they

were forced to leave their house and to take refuge in the miserable den

we found them in. There, to add to their misfortunes, the man was seized

with rheumatism and had to take to bed. The young woman, unacquainted

with the method of obtaining parochial relief, and apparently loth to

avail herself of such assistance, sold the furniture bit by bit until

the barest necessaries only were left. Then they began to experience

absolute starvation. It was a Thursday night when we saw them, and the

father and mother had not tasted any food since the Wednesday morning

except a half-penny bran scone; while a single biscuit between them was

all the nourishment that the children had got. Certainly the haggard,

hunger-bitten appearance of the family bore out the truth of the

statement. During the preceding fortnight not a soul had entered the

door, saving a well-intentioned elderly lady, who had called one Sunday

and left a religious tract—not a very satisfying allowance among four

starving mortals.

This was a case of starving

respectability. But when starvation is found hand in hand with filth and rags, the effect

produced upon the observer is almost staggering.

One night, on chancing to open the door of a room in a Cowgate close,

an involuntary exclamation of horror escaped our lips. It was a small

apartment, in size about three strides either way, in the last stages of

decay. The walls were brown with dirt. A dirty bedstead, covered with a

few clothes in a state of filth harmonising with the general foulness

of the room, stood in one corner; a tumble-down table was propped up in

another; and through the smoke that filled the room we could

indistinctly see, huddling round the fire, the raggedest and dirtiest

group of human beings we ever set eyes on.

Seated on rude benches round the fire, stretching out their hands

greedily towards the feeble flames, were a man and his wife, a girl of

about ten years of age, and two boys of younger age; and in a box

resembling a cradle lay an infant of a few weeks. The boys were tattered

enough in all conscience; one of them had on only a fragmentary shirt,

and lower garments many sizes too large for him, suspended by a single

brace. But as a picturesque raggamuffin he was entirely cast into the

shade by his sister. Her face had upon it the accumulated dirt of weeks; her dishevelled

hair had long been

innocent of the comb; part of the skirt of an old dress was thrown over

her shoulders, and a rag of indefinite shape and origin was tied round

her waist. There was nothing between these worn-out shreds and her bare

skin, as her father demonstrated by drawing aside the rags and

uncovering the dirt-engrained body.

This was a case of terrible destitution. There was not a morsel of

food in the house, and no prospect of getting any. The father, a mason’s

labourer, had been disabled by an accident to his leg three weeks

before, and was unable to work. During that time they had received

half-a-crown a week from the Parochial Board; but it will be allowed

that five sixpences a week are starvation rations for a family of six

souls. The eagerness of these poor creatures at the mention of bread was

touching to behold. The small boy fairly tumbled down the stair after us

in his hurry to get the loaf we purchased at a neighbouring shop.

Appalling as was this picture of want and wretchedness, it was

surpassed in gruesomeness by an experience we had in another hovel in

Covenant Close, High Street. The room was like many others in that

locality—small, ill-ventilated, dirty to the last degree, and in a state of miserable disrepair.

Though the night was one of the coldest we had this winter, there was no

fire, and from the mantelshelf a lamp in which the oil was all but

exhausted, gave out a flickering light that served only to reveal the

wretchedness of the surroundings. A broken chair stood by the cheerless

hearth, and this was all the furniture with the exception of a bed, in

which, Wrapped in ragged blankets, lay a pale-faced, un-washed boy. But

it was the appearance of the woman who opened the door that struck us

with a feeling akin to horror. She was literally half naked. Her feet

were bare; a short, tattered gown scarce covered the calves of her legs; her dress, open at the neck, showed her grimy breast, and round her

head was bound a scrap of flannel, with which she tried to assuage the

pangs of neuralgia. Neuralgia under the most advantageous circumstances

is torture enough; what it must have been with the added pains of

hunger and cold would baffle the power of language to describe.

This woman’s story was short, and as grievous as short. Her husband,

a labourer, was idle, thrown out of work by the railway strike. At that

moment he was out searching for employment. She had no money, no food,

no coal, no oil for the lamp, and was just about to huddle in beside her child for the sake

of the little warmth the scanty blankets could afford. She was ill and

starving, but it was needless to tell us that. The ghastly figure before

us told its own tale without words. We gave the woman a little money to

stave off starvation a little longer, and then left this grim chamber of

horrors. From a neighbour we learned that the poor creature had been

apprehended by the police that morning for stealing a piece of coal, but

that the authorities, evidently moved with compassion at her pitiable

plight, had detained her in the cells for only three hours, and then set

her free to go “home.” One is inclined to think that, under the

circumstances, freedom was not a tiling to be desired.

Such privation as this could not be of long duration; in whatever

way it ended it must of necessity be sharp and short. Less startling, it

may be, but every whit as saddening, are the cases of chronic

destitution which are found with distressing frequency in one’s

wanderings in the slums. Away down in those sunless, joyless regions

there are hundreds of hapless beings who, even by incessant toil, cannot

keep their heads above water. They do not know what it is to have a

short respite from anxiety for their next meal.

They seldom experience the satisfaction of having a full meal; hunger

is ever their companion. In the hovels of Lower Greenside may be found

not a few instances of poor families whom stress of circumstances has

driven from comfortable and respectable homes. The true blatant, brutal

slum “moucher” born and bred is indigenous to the Cowgate and the

Grassmarket, and the adjacent localities; but, so far as we could judge,

Lower Greenside hides within its sombre depths a different class of

people—unfortunate creatures of undoubted respectability who have been

forced to retreat step by step before their gaunt enemy Poverty, until

at length they found themselves immured in those dismal subterraneous

regions.

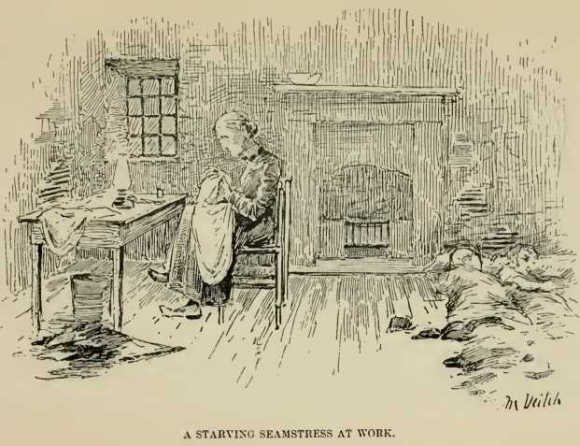

A case illustrative of this gradual descent was that of a seamstress,

who lived in a room there with her two children. Though she was yet

under middle age, her face was worn and deeply lined, while her haggard,

anxious face and bent figure told of a hard struggle for existence. Once

she had been better off, her husband being a tailor in good employment.

But he died, and she supported herself and her two children by working

as a machinist. Soon, however, her eyesight, which had never been of the

best, began to fail. Day after day brought increasing difficulty; she struggled against the infirmity; but eventually she lost

her situation, for she was unable to do the fine work demanded of her.

Now she kept body and soul together by doing odd dressmaking jobs where

careful workmanship was not necessary, such as repairing or making down

an old dress for any of her poor neighbours. In this way, and by doing

such charing as she could get, she made from half-a-crown to three and

sixpence a week, and even this wretched pittance was precarious. This

was all she had with which to pay her rent of one and sixpence a week,

and to provide food, coal, and oil. Indeed, she said, were it not for an

occasional soup ticket and scraps of food given to her by tender-hearted

neighbours almost as poor as herself, she could not live at all, for

often she was entirely without food or money, and did not know where her

next meal was to conic from.

She had applied to the Parochial Board, but had been refused

assistance, because she lived in a “land” which had an evil repute, and

the parochial authorities are naturally chary of giving relief to

persons whom they suspect of leading an immoral life. Could she, then,

not remove to respectable locality? But here she was confronted with an insurmountable difficulty. To remove, money was

necessary, for she could not get another house unless she paid the

landlord a month’s rent in advance, which is the invariable rule with

the proprietors of those one-roomed houses. A month’s rent meant six

shillings, and to her six shillings was a great sum of money, quite

beyond her power to scrape together.

And thus she remained, chained to the rock; toiling in hunger and

squalor for her forty pence a week, and glad that by so doing she could

keep her bairns with her in that dilapidated and almost furnitureless

shelter.

These arc mere sketches of scenes whose hideousness can only be

realised when viewed at close quarters, and the contemplation of which

produces a sense of helplessness bordering upon despair. You may do your

best to relieve a hungering family here and there, but you do so with

the feeling that you might as well try to dip the ocean dry with a

teaspoon. And yet the public seem to have the comfortable notion that

though the poor of Edinburgh have their hard times like other people,

they rarely suffer from actual starvation. This is a reasonable belief

when one considers the huge sum that is spent in charitable objects;

but, nevertheless, the public are labouring under a sad delusion. |