|

We are no “Special

Commissioners” deputed to paint lurid pictures of slum liorrors; we are

not sentimental shimmers who run hither and thither in the search for

social sores over which to gush and weep; we see no reason for abusing

the authorities, or the administrators of public or private charities;

we do not even cherish a theory, the carrying out of which would secure

the salvation of the “submerged tenth.” We simply wish, in these

articles, to draw a few unexaggerated pictures, or rather sketches, of

the conditions under which the inhabitants of those lower regions exist;

to tell something of their homes and their mode of life, their struggles

and their sufferings, with which we have become acquainted in the course

of long wanderings among the courts and closes and back streets of the

city.

This, we believe, is not

yet a work of supererogation ; for, notwithstanding all that has been

said and written of the poorer classes, the quarters where they

congregate are still “dark places” to all but a comparative few. To the

vast majority the “one-roomed house,” the squalor and destitution of the

poor, are but the merest abstractions, or are vaguely associated with

notorious East End localities. It is only when we come face to face with

the misery itself, instead of confining our knowledge to that derived

from the reports of charitable institutions, that we can realise its

awful actuality.

We need not travel four

hundred miles to Whitechapel; we have a Whitechapel at our own doors,

gruesome enough to satisfy the cravings of the sensation hunter, big

enough to absorb all our time, money, and philanthropic zeal.

A walk through the

Grassmarket or Cowgate, or down the Lawnmarket and Canongate, is at

times a very depressing experience; but one has to explore the huge

tenements that tower on either side of the street, to enter the houses

and speak with the people, to arrive at an adequate idea of what life in

some parts of the slums means. A night spent in such an

exploration—climbing foul and rickety stairs, groping vour wav along a

network of dark, narrow passages, and peering into the dismal dens which

the wretched inhabitants (and their landlords) call “houses”—a night

passed in this manner will give an experience of horrors that will for

ever remain imprinted on the memory.

Go into any one of the

courts in the Lawn-market, for instance ; glance up at the rows of

windows, and then reflect for a minute or two. Windows

everywhere—looking to front, to back, into courts and closes; and each

one of them probably represents a “one-roomed house,” inhabited by from

two to eight or nine persons. The rooms, the spacious chambers of the

aristocracy of Edinburgh, have been partitioned off into small box-like

apartments, like the cells of a honeycomb. Everybody is familiar with

the filth of the closes and courts : these, then, need not be further

described. The stairs are in a corresponding state of foulness. The

seemingly interminable passages which penetrate in all directions into

these human warrens are narrow, and in general very badly lighted ; in

many the darkness seems almost to be palpable, so dense is it. Along

these corridors the doors of the rooms are ranged within a few feet of

each other. A close, sickening odour pervades the passages. It is an

indescribable smell—a compound of all the foul vapours escaping from

numberless reeking hovels. Sometimes when you enter a room, fumes like

the quintessence of all villainous smells combined, make yon gasp, and

then, rushing down to the very foundations of your vitals, cause a

sensation as if the stomach were trying to turn a somersault. But

conquering an instinctive desire to shut the door and beat a retreat,

you enter the room and look around you.

The room, for which a

weekly rent of from one and threepence to half-a-crown is paid, is

small, dirty, and dingy. The walls are black with the smoke and dirt of

years; here and there the plaster has fallen off in patches, and reveals

the laths beneath. The floor looks as if soap and water were still

unknown in these regions : likewise the crazy deal table—if there

happens to be one. There may be a chair with a decayed back, but

frequently a roughly-made stool or an upturned box does duty instead.

And the bed ! These lairs—for the word “bed” may suggest erroneous ideas

of luxury—have long been a marvel to us; inasmuch as it is difficult to

imagine how blankets, which presumably were once white, have assumed a

hue so dark. They appear to have been steeped in a solution of soot and

water—blankets, pillows, and mattress, or what stand for such. Generally

the bed is a wooden one, a venerable relic of bygone fashions, bought

for a trifle from the furniture broker on the other side of the street.

But very often a bedstead is not included in the furnishings of the

chamber, in which case the family couch consists of a mattress or a

bundle of rags, or some straw laid in the least draughty corner of the

room, and covered over with any kind of rags that can be gathered

together.

There a whole family will

lie down at night, and when the cold is intense, and the piercing wind

whistles through the chinks in the window frames, right glad they arc to

huddle together for the sake of warmth. It is 110 uncommon thing to sec

five or six, or even seven, persons in one bed—father, mother, and four

or five children, one foetid intertwined mass of humanity. The

unspeakably horrible results of this overcrowding need not be described;

they can be readily imagined. For it is not only children who are packed

together within the four walls of one chamber. It is quite a usual thing

to find grown-up people herding together in one small room, without any

pretence of privacy or decency.

In a room in the

Lawnmarket we found a man and his wife in bed, both unwell. The husband

had been out of health and unable to work for twelve months, and he and

his wife were supported by a daughter of twenty years of age, who earned

seven shillings and sixpence a week, and shared their room, and their

led, with them. And they would think you had queer notions if you

expressed surprise at this natural arrangement.

Another room—this one in

the Castle Wynd— presented a scene that is only too easily paralleled in

any part of our slums. It was typical of the poor man’s home. The room

was filthy beyond description. From the blackened walls the paper hung

in shreds, and in one corner the damp had discoloured the plaster beyond

the power of whitewash to restore. A feeble light from a paraffin lamp

shed its melancholy rays over a group of two men, two girls, and a boy

cowering round a cinder fire which they were in vain endeavouring to

coax into a flame. Beside them, on a bundle of rags on the floor, lay a

woman and two grown-up daughters; and 011 a decrepit bedstead, curled up

among a few foul cloths that no one would think of calling bed-clothes,

a man was sleeping off the effects of a two-days’ carouse.

A HOVEL IN LOWER GREENSIDE.

In this dark, dam}) den,

the weekly rent of which was two shillings and fourpence, the man, his

wife, and five children, the eldest of whom was a girl of eighteen,

lived—under what conditions we shall leave the reader to depict for

himself.

But this is almost a

desirable residence compared with some of the abodes that may be seen

any day of the week. In Lower Greenside, where there are some execrable

specimens of one-roomed houses, we stumbled across a den about twelve

feet square. It was a debateable point which was the more hideous, the

room or its occupants. Furniture there was none, unless a shakedown of

rags, a stool, and an empty orange box may go by that name. In the grate

an old boot was burning, for the supply of cinders had run out. On one

side of the fire sat an unkempt virago, with a baby at her breast and a

pipe in her mouth. Opposite to her crouched an aged woman, whose grey

dishevelled hair, hooked nose, and brown, minutely wrinkled face gave

her a very witch-like appearance. Crosslegged between them sat a boy of

about ten years of age. This beldam, having reached the stage of

intoxication, was venting her spleen in a shower of oaths and curses

upon her companion with the baby and the pipe : but the latter treated

her volleys of vituperation with the calmness bred of use and wont ;

only at intervals removing her pipe from her mouth and commanding the

old woman to “shut up,” an injunction always followed by a fierce,

complicated oath.

A feature of this low

life that impresses one with painful vividness is the total absence of

anything approaching rational enjoyment or employment. When a man in

comfortable circumstances goes home from his day’s work, he generally

finds a cheery hearth and a warm meal awaiting him. Then, if he does not

go out for a walk, or to visit friends, or to some place of

entertainment, he puts his slippered feet on the fender and has his pipe

and his newspaper; or, if he is a family man, he enjoys the company of

his wife and children. At all events he is fed and warm, and his mind is

more or less at ease.

The forlorn being of whom

we write returns to the hovel he calls his home, after, it may be, a day

spent in a fruitless search for work. He finds nothing there to cheer or

attract him. Dirt and desolation everywhere this better-half not

remarkable for her tidiness. A swarm of ragged, hungry bairns are

sprawling about the

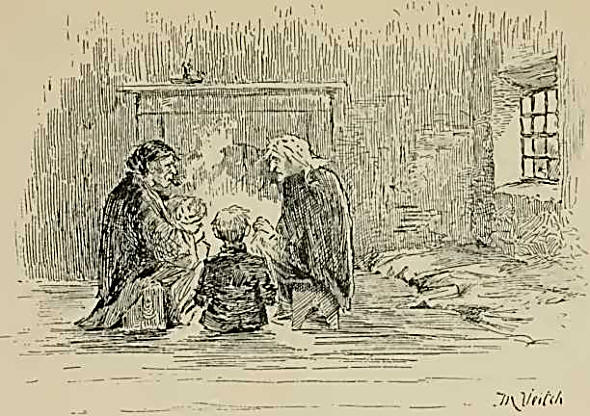

A FAMILY IN A ONE-ROOMED HOUSE.

floor. It depends on

reliance and the luck of the day whether there is any supper or not.

Possibly there is not a crust in the house. Though the night is bitterly

cold, there is only a handful of smouldering cinders in the grate, and a

chillness that penetrates to the very marrow pervades the room. Books or

newspapers he has none; probably he could not read them if he had any.

The night is too cold for loafing at the “close-mouth”—a favourite

summer pastime of our slum denizens; so all he can do is to kill time

till he shuffles off to bed.

It sickens the heart to

see the hopeless, aimless demeanour of a family group such as this.

There they sit, as close to the meagre fire as possible; gloomy

emptiness on all sides. They do nothing; of conversation they have

little, only an occasional remark is dropped in a listless way. When one

surprises a household in this attitude, he is impressed with the idea

that this cluster of silent figures are expecting something—waiting for

something to turn up. But if they are expectant, it is of something that

never comes. At length, hungry, shivering, utterly wretched, they throw

themselves upon the pallet of straw and rags, and for a time forget

their misery in sleep. |