|

WALKING into the interior of Skye is

like walking into antiquity; the present is behind

you, your face is turned toward Ossian. In the quiet silent wilderness you

think of London, Liverpool, Edinburgh, or whatever great city it may be

given you to live and work in, as of something of which you were cognisant

in a former existence. Not only do you breathe the air of antiquity; but

everything about you is a veritable antique. The hut by the road-side,

thatched with turfs, smoke issuing from the roof, is a specimen of one of

the oldest styles of architecture in the world. The crooked spade with

which the crofter turns over the sour ground carries you away into fable.

You remove a pile of stones on the moor, and you come to a flagged chamber

in which there is a handful of human bones—whose, no one can tell.

Duntulm and Dunsciach moulder on their crags, but the song the passing

milkmaid sings is older than they. You come upon old swords that were once

bright and athirst for blood; old brooches that once clasped plaids; old

churchyards with carvings of unknown knights on the tombs; and old men who

seem to have inherited the years of the eagle or the crow. These human

antiques are, in their way, more interesting than any other: they are the

most precious objects of virtu of which the island can boast. And

at times, if you can keep ear and eye open, you stumble on forms of life,

relations of master and servant, which are as old as the castle on the

crag or the cairn of the chief on the moor. Cash payment is not the

"sole nexus between man and man." In these remote regions your

servants’ affection for you is hereditary as their family name or their

family ornaments; your foster-brother would die willingly for you; and if

your nurse had the writing of your epitaph, you would be the bravest,

strongest, handsomest man that ever walked in shoe leather or out of it.

The

house of my friend Mr M’Ian is set down on the shore of one of the great

Lochs that intersect the island; and as it was built in smuggling times,

its windows look straight down the Loch towards the open sea. Consequently

at night, when lighted up, it served all the purposes of a lighthouse: and

the candle in the porch window, I am told, has often been anxiously

watched by the rough crew engaged in running a cargo of claret or brandy

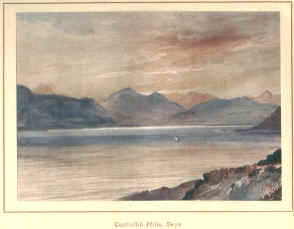

from Bordeaux. Right opposite, on the other side of the Loch, is the great

rugged fringe of the Cuchullin hills; and lying on the dry summer grass

you can see it, under the influence of light and shade, change almost as

the expression of a human face changes. Behind the house the ground is

rough and broken, every hollow filled, every knoll plumaged with birches,

and between the leafy islands, during the day, rabbits scud continually,

and in the evening they sit in the glades and wash their innocent faces. A

mile or two back from the house a glen opens into soft green meadows,

through which a stream flows; and on these meadows Mr M’Ian, when the

weather permits, cuts and secures his hay. The stream is quiet enough

usually, but after a heavy day’s rain, or when a waterspout has burst up

among the hills, it comes down with a vengeance, carrying everything

before it. On such occasions its roar may be heard a mile away. About a

pistol-shot from the house the river is crossed by a plank bridge, and in

fine weather it is a great pleasure to sit down there and look about one.

The stream flows sluggishly over rocks, in the deep places of a purple or

port-wine colour, and lo! behind you, through the arch, slips a sunbeam,

and just beneath the eye there gleams a sudden chasm of brilliant amber.

The sea is at ebb, and the shore is covered with stones and dark masses of

sea-weed; and the rocks a hundred yards off—in their hollows they hold

pools of clear sea-water in which you can find curious and delicately-coloured

ocean blooms—are covered with orange lichens, which contrast charmingly

with the masses of tawny dulse and the stone-littered shore on the one

side, and the keen blue of the sea on the other. Beyond the blue of the

sea the great hills rise, with a radiant vapour flowing over their crests.

Immediately to the left a spur of high ground runs out to the sea edge,—the

flat top smooth and green as a billiard table, the sheep feeding on it

white as billiard balls,—and at the foot of this spur of rock a number

of huts are collected. They are halt lost in an azure veil of smoke, you

smell the peculiar odour of peat reek, you see the nets lying out on the

grass to dry, you hear the voices of children. Immediately above, and

behind the huts and the spur of high ground, the hill falls back, the

whole breast of it shaggy with birch-wood; and just at the top you see a

clearing and a streak of white stony road, leading into some other region

as solitary and beautiful as the one in which you at present are. And

while you sit on the bridge in a state of half-sleepy contentment—a bee

nuzzling in a bell-shaped flower within reach of your stick, the sea-gulls

dancing silent quadrilles overhead, the white lightning flash of a rabbit

from copse to copse twenty yards off— you hear a sharp whistle,

then a shout, and looking round there is M’Ian himself standing on a

height, his figure clear against the sky: and immediately the men

tinkering the boat on the shore drop work and stand and stare, and out of

the smoke that wraps the cottages rushes bonnetless, Lachian Dhu, or

Donald Roy, scattering a brood of poultry in his haste, and marvelling

much what has moved his master to such unwonted exertion. The

house of my friend Mr M’Ian is set down on the shore of one of the great

Lochs that intersect the island; and as it was built in smuggling times,

its windows look straight down the Loch towards the open sea. Consequently

at night, when lighted up, it served all the purposes of a lighthouse: and

the candle in the porch window, I am told, has often been anxiously

watched by the rough crew engaged in running a cargo of claret or brandy

from Bordeaux. Right opposite, on the other side of the Loch, is the great

rugged fringe of the Cuchullin hills; and lying on the dry summer grass

you can see it, under the influence of light and shade, change almost as

the expression of a human face changes. Behind the house the ground is

rough and broken, every hollow filled, every knoll plumaged with birches,

and between the leafy islands, during the day, rabbits scud continually,

and in the evening they sit in the glades and wash their innocent faces. A

mile or two back from the house a glen opens into soft green meadows,

through which a stream flows; and on these meadows Mr M’Ian, when the

weather permits, cuts and secures his hay. The stream is quiet enough

usually, but after a heavy day’s rain, or when a waterspout has burst up

among the hills, it comes down with a vengeance, carrying everything

before it. On such occasions its roar may be heard a mile away. About a

pistol-shot from the house the river is crossed by a plank bridge, and in

fine weather it is a great pleasure to sit down there and look about one.

The stream flows sluggishly over rocks, in the deep places of a purple or

port-wine colour, and lo! behind you, through the arch, slips a sunbeam,

and just beneath the eye there gleams a sudden chasm of brilliant amber.

The sea is at ebb, and the shore is covered with stones and dark masses of

sea-weed; and the rocks a hundred yards off—in their hollows they hold

pools of clear sea-water in which you can find curious and delicately-coloured

ocean blooms—are covered with orange lichens, which contrast charmingly

with the masses of tawny dulse and the stone-littered shore on the one

side, and the keen blue of the sea on the other. Beyond the blue of the

sea the great hills rise, with a radiant vapour flowing over their crests.

Immediately to the left a spur of high ground runs out to the sea edge,—the

flat top smooth and green as a billiard table, the sheep feeding on it

white as billiard balls,—and at the foot of this spur of rock a number

of huts are collected. They are halt lost in an azure veil of smoke, you

smell the peculiar odour of peat reek, you see the nets lying out on the

grass to dry, you hear the voices of children. Immediately above, and

behind the huts and the spur of high ground, the hill falls back, the

whole breast of it shaggy with birch-wood; and just at the top you see a

clearing and a streak of white stony road, leading into some other region

as solitary and beautiful as the one in which you at present are. And

while you sit on the bridge in a state of half-sleepy contentment—a bee

nuzzling in a bell-shaped flower within reach of your stick, the sea-gulls

dancing silent quadrilles overhead, the white lightning flash of a rabbit

from copse to copse twenty yards off— you hear a sharp whistle,

then a shout, and looking round there is M’Ian himself standing on a

height, his figure clear against the sky: and immediately the men

tinkering the boat on the shore drop work and stand and stare, and out of

the smoke that wraps the cottages rushes bonnetless, Lachian Dhu, or

Donald Roy, scattering a brood of poultry in his haste, and marvelling

much what has moved his master to such unwonted exertion.

My friend’s white house

is a solitary one, no other dwelling of the same kind being within eight

miles of it. In winter, wind and rain beat it with a special spite; and

the thunder of the sea creeps into your sleeping ears, and your dreams are

of breakers and reefs, and ships going to pieces, and the cries of

drowning men. In summer, it basks as contentedly on its green knoll; green

grass, with the daisy wagging its head in the soft wind, runs up to the

very door of the porch. But although solitary enough—so solitary, that

if you are asked to dine with your nearest neighbour you must mount and

ride—there are many more huts about than those we have seen nestling on

the shore beneath the smooth green plateau on which sheep are feeding. If

you walk along to the west,—and a rough path it is, for your course is

over broken boulders,—you come on a little bay with an eagle’s nest of

a castle perched on a cliff, and there you will find a school-house and a

half-a-dozen huts, the blue smoke steaming out of the crannies in the

walls and roofs. Dark pyramids of peat are standing about, sheep and cows

are feeding on the bits of pasture, gulls are weaving their eternal dances

above, and during the day the school-room is murmuring like a beehive—only

a much less pleasant task than the making of honey is going on within.

Behind the house to the east, hidden by the broken ground and the masses

of birch-wood, is another collection of huts; and in one of these lives

the most interesting man in the place. He is an old pensioner, who has

seen service in different quarters of the world; and frequently have I

carried him a string of pigtail, and shared his glass of usquebaugh, and

heard him, as he sat on a stone in the sunshine, tell tales of barrack

life in Jamaica ; of woody wildernesses filled with gorgeous undergrowth,

of parasites that climbed like fluttering tongues of fire, and of the

noisy towns of monkeys and parrots in the upper branches. I have heard him

also severely critical on the different varieties of rum. Of every fiery

compound he had a catholic appreciation, but rum was his special favourite—being

to him what a Greek text was to Porson, or an old master to Sir George

Beaumont. So that you see, although Mr M’Ian’s house was in a sense

solitary, yet it was not altogether bereaved of the sight and sense of

human habitations. On the farm there were existing perhaps, women and

children included, some sixty souls; and to these the relation of the

master was peculiar, and perhaps without a parallel in the island.

When, nearly half-a-century

ago, Mr M’Ian left the army and became tacksman, he found cotters on his

farm, and thought their presence as much a matter of course as that

limpets should be found upon his rocks. They had their huts, for which

they paid no rent; they had their patches of corn and potato ground, for

which they paid no rent. There they had always been, and there, so far as

Mr M’Ian was concerned, they would remain. He had his own code of

generous old-fashioned ethics, to which he steadily adhered; and the man

who was hard on the poor, who would dream of driving them from the places

in which they were born, seemed to him to break the entire round of the

Commandments. Consequently the huts still smoked on the hem of the shore

and among the clumps of birch-wood. The children who played on the green

when he first became tacksman grew up in process of time, and married; and

on these occasions he not only sent them something on which to make merry

withal, but he gave them—what they valued more—his personal presence;

and he made it a point of honour, when the ceremony was over, to dance the

first reel with the bride. When old men or children were sick, cordials

and medicines were sent from the house; when old man or child died, Mr M’Ian

never failed to attend the funeral. He was a Justice of the Peace; and

when disputes arose amongst his own cotters, or amongst the cotters of

others—when, for instance, Katy M’Lure accused Effie M’Kean of

stealing potatoes when Red Donald raged against Black Peter on some matter

relating to the sale of a dozen lambs when Mary, in her anger at the loss

of her sweetheart, accused Betty (to whom said sweetheart had transferred

his allegiance) of the most flagrant breaches of morality—the contending

parties were sure to come before my friend; and many a rude court of

justice I have seen him hold at the door of his porch. Arguments were

heard pro and con, witnesses were examined, evidence was duly sifted and

weighed, judgment was made, and the case dismissed; and I believe these

decisions gave in the long run as much satisfaction as those delivered in

Westminster or the Edinburgh Parliament-House. Occasionally, too, a single

girl or shepherd, with whose character liberties were being taken, would

be found standing at the porch-door anxious to make oath that they were

innocent of the guilt or the impropriety laid to their charge. Mr M’Ian

would come out and hear the story, make the party assert his or her

innocence on oath, and deliver a written certificate to the effect that in

his presence, on such and such a day, so and so had sworn that certain

charges were unfounded, false, and malicious. Armed with this certificate,

the aspersed girl or shepherd would depart in triumph. He or she had

passed through the ordeal by oath, and nothing could touch them farther.

Mr M’Ian paid rent for

the entire farm; but to him the cotters paid no rent, either for their

huts or for their patches of corn and potato ground. But the cotters were

by no means merely pensioners — taking, and giving nothing in return.

The most active of the girls were maids of various degree in Mr M’Ian’s

house; the cleverest and strongest of the lads acted as shepherds,

&c.; and these of course received wages. The grown men amongst the

cotters were generally at work in the south, or engaged in fishing

expeditions, during summer; so that the permanent residents on the farm

were chiefly composed of old men, women, and children. When required, Mr M’Ian

demands the services of these people just as he would the services of his

household servants, and they comply quite as readily. If the crows are to

be kept out of the corn, or the cows out of the turnip-field, an urchin is

remorselessly reft away from his games and companions. If a boat is out of

repair, old Dugald is deputed to the job, and when his task is completed,

he is rewarded with ten minutes’ chat and a glass of spirits up at the

house. When fine weather comes, every man, woman, and child is ordered to

the hay-field, and Mr M’Ian potters amongst them the whole day, and

takes care that no one shirks his duty. When his corn or barley is ripe

the cotters cut it, and when the harvest operations are completed, he

gives the entire cotter population a dance and harvest-home. But between

Mr M’Ian and his cotters no money passes; by a tacit understanding he is

to give them house, corn-ground, potato-ground, and they are to remunerate

him with labour.

Mr M’Ian, it will be

seen, is a conservative, and hates change; and the social system by which

he is surrounded wears an ancient and patriarchal aspect to a modern eye.

It is a remnant of the system of clanship. The relation of cotter and

tacksman, which I have described, is a bit of antiquity quite as

interesting as the old castle on the crag—nay, more interesting,

because we value the old castle mainly in virtue of its representing an

ancient form of life, and here is yet lingering a fragment of the ancient

form of life itself. You dig up an ancient tool or weapon in a moor, and

place it carefully in a museum: here, as it were, is the ancient tool or

weapon in actual use. No doubt Mr M’Ian’s system has grave defects: it

perpetuates comparative wretchedness on the part of the cotters, it

paralyses personal exertion, it begets an ignoble contentment; but on the

other hand it sweetens sordid conditions, so far as they can be sweetened,

by kindliness and good services. If Mr M’Ian’s system is bad, he makes

the best of it, and draws as much comfort and satisfaction out of it, both

for himself and for others, as is perhaps possible.

Mr M’Ian’s speech was

as old-fashioned as he was himself; ancient matters turned up on his

tongue just as ancient matters turned up on his farm. You found an old

grave or an old implement on the one, you found an old proverb or an old

scrap of a Gaelic poem on the other. After staying with him some ten days,

I intimated my intention of paying a visit to my friend the Landlord—with

whom Fellowes was then staying—who lived some forty miles off in the

northwestern portion of the island. The old gentleman was opposed to rapid

decisions and movements, and asked me to remain with him yet another week.

When he found I was resolute he glanced at the weather-gleam, and the

troops of mists gathering on Cuchullin, muttering as he did so, "Make

ready my galley,’ said the king, ‘I shall sail for Norway on

Wednesday.’ ‘Will you,’ said the wind, who, flying about, had

overheard what was said, ‘you had better ask my leave first.’"

Between the Landlord and M’Ian

there were many likenesses and divergences. Both were Skye-men by birth,

both had the strongest love for their native island, both had the

management of human beings, both had shrewd heads, and hearts of the

kindest texture. But at this point the likenesses ended, and the

divergences began. Mr M’Ian had never been out of the three kingdoms.

The Landlord had spent the best part of his life in India, was more

familiar with huts of ryots, topes of palms, tanks in which the indigo

plant was steeping, than with the houses of Skye cotters and the processes

of sheep-farming. He knew the streets of Benares or Delhi better than he

knew the streets of London; and, when he first came home, Hindostanee

would occasionally jostle Gaelic on his tongue. The Landlord too, was

rich, would have been considered a rich man even in the southern cities;

he was owner of many a mile of moorland, and the tides of more than one

far-winding Loch rose and rippled on shores that called him master. In my

friend the Landlord there was a sort of contrariety, a sort of mixture or

blending of opposite elements which was not without its fascination. He

was in some respects a resident in two worlds. He liked motion; he had a

magnificent scorn of distance: to him the world seemed comparatively

small; and he would start from Skye to India with as much composure as

other men would take the night train to London. He paid taxes in India and

he paid taxes in Skye. His name was as powerful in the markets of Calcutta

as it was at the Muir of Ord. He read the Hurkaru and the Inverness

Courier. He had known the graceful salaam of the East, as he now knew

the touched bonnets of his shepherds. And in living with him, in talking

with him, one was now reminded of the green western island on which sheep

fed, anon of tropic heats, of pearl and gold, of mosque and pinnacle

glittering above belts of palm-trees. In his company you were in

imagination travelling backwards and forwards. You made the overland route

twenty times a day. Now you heard the bagpipe, now the monotonous beat of

the tom-tom and the keen clash of silver cymbals. You were continually

passing backwards and forwards, as I have said. You were in the West with

your half-glass of bitters in the morning, you were in the East with the

curry at dinner. Both Mr M’Ian and the Landlord had the management of

human beings, but their methods of management were totally different. Mr M’Ian

accepted matters as he found them, and originating nothing, changing

nothing, contrived to make life for himself and others as pleasant as

possible. The Landlord, when he entered on the direction of his property,

exploded every ancient form of usage, actually ruled his tenants; would

permit no factor, middle-man, or go-between; met them face to face, and

had it out with them. The consequence was that the poor people were at

times sorely bewildered. They received their orders and carried them out,

with but little sense of the ultimate purpose of the Landlord—just as

the sailor, ignorant of the principles of navigation, pulls ropes and

reefs sails and does not discover that he gains much thereby, the same

sea-crescent being around him day by day, but in due time a cloud rises on

the horizon, and he is in port at last.

As M’Ian had predicted, I

could only move from his house if the weather granted permission and this

permission the weather did not seem disposed to grant. For several days it

rained as I had never seen it rain before; a waterspout, too had burst up

among the hills, and the stream came down in mighty flood. There was great

hubbuh at the house. Mr M’Ian’s hay, which was built in large stacks

in the valley meadows, was in danger, and the fiery cross was sent through

the cotters. Up to the hay-fields every available man was despatched with

carts and horses, to remove the stacks to some spot where the waters could

not reach them; while at the bridge nearer the house women and boys were

stationed with long poles, and what rudely-extemporised implements Celtic

ingenuity could suggest, to intercept and fish out piles and trusses which

the thievish stream was carrying away with it seaward. These piles and

trusses would at least serve for the bedding of cattle. For three days the

rainy tempest continued; at last, on the fourth, mist and rain rolled up

like a vast curtain in heaven, and then again were visible the clumps of

birch-wood, and the bright sea and the smoking hills, and far away on the

ocean floor Rum and Canna, without a speck of cloud on them, sleeping in

the coloured calmness of early afternoon. This uprising of the elemental

curtain was, so far as the suddenness of the effect was concerned, like

the uprising of the curtain of the pantomime on the transformation scene—all

at once a dingy, sodden world had become a brilliant one, and all the

newly-revealed colour and brilliancy promised to be permanent.

Of this happy change in the

weather I of course took immediate advantage. About five o’clock in the

afternoon my dog-cart was brought to the door; and after a parting cup

with Mr M’Ian—who pours a libation both to his arriving, and his

departing guest—I drove away on my journey to remote Portree, and to the

unimagined country that lay beyond Portree, but which I knew held Dunvegan,

Duntuim, Macleod’s Tables, and Quirang. I drove up the long glen with a

pleasant exhilaration of spirit. I felt grateful to the sun, for he had

released me from rainy captivity. The drive, too, was pretty; the stream

came rolling down in foam, the smell of the wet birch-trees was in the

brilliant air, every mountain-top was strangely and yet softly distinct;

and looking back, there were the blue Cuchullins looking after me, as if

bidding me farewell! At last I reached the top of the glen, and emerged on

a high plateau of moorland, in which were dark inky tarns with big white

water-lilies on them; and skirting across the plateau I dipped down on the

parliamentary road, which, like a broad white belt, surrounds Skye. Better

road to drive on you will not find in the neighbourhood of London itself!

and just as I was descending, I could not help pulling up. The whole scene

was of the extremest beauty — exquisitely calm, exquisitely coloured. On

my left was a little lake with a white margin of water-lilies, a rocky

eminence throwing a shadow half-way across it. Down below, on the

sea-shore, was the farm of Knock, with white outhouses and pleasant

patches of cultivation, the school-house, and the church, while on a low

spit of land the old castle of the Macdonalds was mouldering. Still lower

down and straight away stretched the sleek blue Sound of Sleat, with not a

sail or streak of steamer smoke to break its vast expanse, and with a

whole congregation of clouds piled up on the horizon, soon to wear their

evening colours. I let the sight slowly creep into my study of

imagination, so that I might be able to reproduce it at pleasure; that

done, I drove down to Isle Oronsay by pleasant sloping stages of descent,

with green hills on right and left, and along the roadside, like a guard

of honour, the purple stalks of the foxglove.

The evening sky was growing

red above me when I drove into Isle Oronsay, which consists of perhaps

fifteen houses in all. It sits on the margin of a pretty bay, in which the

cry of the fisher is continually heard, and into which the Clansman

going to or coming from the south steams twice or thrice in the week. At a

little distance is a lighthouse with a revolving light,—an idle building

during the day, but when night comes, awakening to full activity,—sending

now a ray to Ardnamurchan, now piercing with a fiery arrow the darkness of

Glenelg. In Isle Oronsay is a merchant’s shop, in which every

conceivable article may be obtained. At Isle Oronsay the post-runner drops

a bag, as he hies on to Armadale Castle. At Isle Oronsay I supped with my

friend Mr Fraser. From him I learned that the little village had been,

like M’Ian’s house, fiercely scourged by rains. On the supper-table

was a dish of trouts. "Where do you suppose I procured these ?"

he asked. "In one of your burns, I suppose." "No such

thing; I found them in my potato-field." "In your potato-field!

How came that about ?" "Why, you see the stream, swollen by

three days’ rain, broke over a potato-field of mine on the hill-side and

carried the potatoes away, and left these plashing in pool and runnel. The

Skye streams have a slight touch of honesty in them !" I smiled at

the conceit, and expounded to my host the law of compensation which

pervades the universe, of which I maintained the trouts on the table were

a shining example. Mr Fraser assented; but held that Nature was a poor

valuator—that her knowledge of the doctrine of equivalents was slightly

defective—that the trouts were well enough, but no reimbursement for the

potatoes that were gone.

Next morning I resumed my

journey. The road, so long as it skirted the sea-shore, was pretty enough;

but the sea-shore it soon left, and entered a waste of brown monotonous

moorland. The country round about abounds in grouse, and was the favourite

shooting-ground of the late Lord Macdonald. By the road-side his lordship

had erected a stable and covered the roof with tin; and so at a distance

it flashed as if the Koh-i-noor had been dropped by accident in that

dismal region. As I went along, the hills above Broadford began to rise;

then I drove down the slope, on which the market was held—the tents all

struck, but the stakes yet remaining in the ground—and after passing the

six houses, the lime-kiln, the church, and the two merchants’ shops, I

pulled up at the inn door, and sent the horse round to the stable to feed

and to rest an hour.

After leaving Broadford the

traveller drives along the margin of the ribbon of salt water which flows

between Skye and the Island of Scalpa. Up this narrow sound the steamer

never passes, and it is only navigated by the lighter kinds of sailing

craft. Scalpa is a hilly island of some three or four miles in length, by

one and a half in breadth, is gray-green in colour, and as treeless as the

palm of your hand. It has been the birthplace of many soldiers. After

passing Scalpa the road ascends; and you notice as you drive along that

during the last hour or so the frequent streams have changed colour. In

the southern portion of the island they come down as if the hills ran

sherry—here they are pale as shallow sea-water. This difference of hue

arises of course from a difference of bed. About Broadford they come down

through the mossy moorland, here they run over marble. Of marble the

island is full; and it is not impossible that the sculptors of the

twentieth century will patronise the quarries of Strath and Kyle rather

than the quarries of Carrara. But wealth is needed to lay bare these

mineral treasures. The fine qualities of Skye marble will never be

obtained until they are laid open by a golden pick-axe.

Once you have passed Scalpa

you approach Lord Macdonald’s deer forest. You have turned the flank of

the Cuchullins now, and are taking them in rear, and you skirt their bases

very closely too. The road is full of wild ascents and descents, and on

your left, for a couple of miles or so, you are in continual presence of

bouldered hill-side sloping away upward to some invisible peak,

overhanging wall of wet black precipice, far-off serrated ridge that cuts

the sky like a saw. Occasionally these mountain forms open up and fall

back, and you see the sterilest valleys running no man knows whither.

Altogether the hills here have a strange weird look. Each is as closely

seamed with lines as the face of a man of a hundred, and these myriad

reticulations are picked out with a pallid gray-green, as if through some

mineral corrosion. Passing along you are strangely impressed with the idea

that some vast chemical experiment has been going on for some thousands of

years; that the region is nature’s laboratory, and that down these

wrinkled hillfronts she had spilt her acids and undreamed-of combinations.

You never think of verdure in connexion with that net-work of gray-green,

but only of rust, or of some metallic discoloration.

You cannot help fancying

that if a sheep fed on one of those hill-sides it would to a certainty be

poisoned. Altogether the sight is very grand, very impressive, and very

uncomfortable, and it is with the liveliest satisfaction that, tearing

down one of the long descents, you turn your back on the mountain

monsters, and behold in front the green Island of Raasay, with its

imposing modern mansion, basking in sunshine. It is like passing from the

world of the gnomes to the world of men.

I have driven across Lord

Macdonald’s deer forest in sunshine and in rain, and am constrained to

confess that, under the latter atmospherical condition, the scenery is the

more imposing. Some months ago I drove in the mail-gig from Sligachan to

Broadford. There was a high wind, the sun was bright, and consequently a

great carry and flight of sunny vapours. All at once, too, every

half-hour or so, the turbulent brightness of wind and cloud was

extinguished by fierce squalls of rain. You could see the coming

rain-storm blown out on the wind toward you like a sheet of muslin cloth.

On it came racing in its strength and darkness, the long straight watery

lines pelting on road and rock, churning in marsh and pool. Over the

unhappy mail-gig it rushed, bidding defiance to plaid or waterproof cape,

and wetting every one to the skin. The mail jogged on as best it could

through the gloom and the fury, and then the sunshine came again, making

to glisten, almost too brightly for the eye, every rain-pool on the road.

In the sunny intervals there was a great race and hurry of towered vapour,

as I said; and when a shining mass smote one of the hill-sides, or

shrouded for a while one of the more distant serrated crests, the

concussion was so palpable to the eye that the car felt defrauded, and

silence seemed unnatural. And when the vast mass passed onward to impinge

on some other mountain barrier, it was singular to notice by what slow

degrees, with what evident reluctance the laggard skirts combed off. All

these effects of rain and windy vapour I remember vividly, and I suppose

that the vividness was partly due to the lamentable condition of a fellow-traveller.

He was a meek-faced man of fifty. He was dressed in sables, his

swallow-tailed coat was thread-bare, and withal seemed made for a smaller

man. There was an uncomfortable space between the wrists of his coat and

his black-thread gloves. He wore a hat, and against the elements had

neither the protection of plaid nor umbrella. No one knew him, to no one

did he explain his business. To my own notion he was bound for a funeral

at some place beyond Portree. He was not

a clergyman—he might have been a schoolmaster who had become green-moulded in some out-of-the-way locality. Of course one or two

of the rainy squalls settled the meek-faced man in the thread-bare sables.

Emerging from one of these he resembled a draggled rook, and the rain was

pouring from the brim of his pulpy hat as it might from the eaves of a

cottage. A passenger handed him his spirit-flask, the meek-faced man took

a hearty pull, and returning it, said plaintively, "I‘m but poorly

clad, sir, for this God-confounded climate." I think often of the

utterance of the poor fellow: it was the only thing he said all the way; and

when I think of it, I see again the rain blown out towards me on the wind

like a waving sheet of muslin cloth, and the rush, the concussion, the

up-break, and the slow reluctant trailing off from the hill-side of the

sunny cloud. The poor man’s plaintive tone is the anchor which holds

these things in my memory.

The forest is of course treeless. Nor are deer seen

there frequently. Although I have crossed it frequently, only once did I

get a sight of antlers. Carefully I crept up, sheltering myself behind a

rocky haunch of the hill to where the herd were lying, and then rushed out

upon them with a halloo. In an instant they were on their feet, and away went the beautiful creatures, doe and fawn, a

stag with branchy head leading. They dashed across a torrent, crowned an

eminence one by one and disappeared. Such a sight is witnessed but seldom;

and the traveller passing through the brown desolation sees usually no

sign of life. In Lord Macdonald’s deer forest neither trees nor deer are

visible.

When once you get quit of the forest you come on a

shooting-box, perched on the sea-shore; then you pass the little village

of Sconser; and, turning the sharp flank of a hill, drive along Loch Sligachan to Sligachan Inn, about a couple of miles

distant. This inn is a famous halting-place for tourists. There are good

fishing streams about, I am given to understand, and through Glen

Sligachan you can find your way to Camasunary, and take the boat from

thence to Loch Coruisk, as we did. It was down this glen that the

messenger was to have brought the tobacco to our peculiar friend. If you

go you may perhaps find his skeleton scientifically articulated by the

carrion crow and the raven. From the inn door the ridges of the Cuchullins

are scen wildly invading the sky, and in closer proximity there are other

hills which cannot be called beautiful. Monstrous, abnormal, chaotic, they

resemble the other hills

on the earth’s surface, as Hindoo deities resemble human beings. The

mountain, whose sharp flank you turned after you passed Sconser, can be

inspected leisurely now, and is to my mind supremely ugly. In summer it is

red as copper, with great ragged patches of verdure upon it, which look by

all the world as if the coppery mass had rusted green. On these green

patches cattle feed from March to October. You bait at Sligachan,— can

dine on trout which a couple of hours before were darting hither and

thither in the stream, if you like,—and then drive leisurely along to

Portree while the setting sun is dressing the wilderness in gold and rose.

And all the way the Cuchullins follow you; the wild irregular outline,

which no familiarity can stale, haunts you at Portree, as it does in

nearly every quarter of Skye.

Portree folds two irregular

ranges of white houses, the one range rising steeply above the other,

around a noble bay, the entrance to which is guarded by rocky precipices.

At a little distance the houses are white as shells, and as in summer they

are all set in the greenness of foliage the effect is strikingly pretty;

and if the sense of prettiness departs to a considerable extent on a

closer acquaintance, there is yet enough left to gratify you so long as

you remain there, and to make it a pleasant place to think about when you

are gone. The lower range of houses consists mainly of warehouses and

fish-stores; the upper, of the main hotel, the two banks, the court-house,

and the shops. A pier runs out into the bay, and here, when the state of

tide permits, comes the steamer, on its way to or from Stornoway and

unlades. Should the tide be low the steamer lies to in the bay, and her

cargo and passengers come to shore by means of boats. She usually arrives

at night; and at low tide, the burning of coloured lights at the

mast-heads, the flitting hither and thither of busy lanterns, the pier

boats coming and going with illumined wakes, and ghostly fires on the

oar-blades, the clatter of chains and the shock of the crank hoisting the

cargo out of the hold, the general hubbub and storm of Gaelic shouts and

imprecations make the arrival at once picturesque and impressive. In the

bay the yacht of the tourist is continually lying, and at the hotel door

his dog-cart is continually departing or arriving. In the hotel parties

arrange to visit Quirang or the Storr, and on the evenings of market-days,

in the large public rooms, farmers and cattle dealers sit over tumblers of

smoking punch and discuss noisily the prices and the qualities of stock.

Besides the hotel and the pier, the banks, and the court-house

already mentioned, there are other objects of interest in the little

island town—three churches, a post-office, a poor-house, and a cloth

manufactory. And it has more than meets the eye—one of the Jameses

landed here on a visitation of the Isles, Prince Charles was here on his

way to Raasay, Dr Johnson and Boswell were here; and somewhere on the

green hilt on which the pretty church stands, a murderer is buried—the

precise spot of burial is unknown, and so the entire hill gets the credit

that of right belongs only to a single yard of it. In Portree the tourist

seldom abides long; he passes through it as a fortnight before he passed

through Oban. It does not seem to the visitor a specially remarkable

place, but everything is relative in this world. It is an event for the

Islesman at Dunvegan or the Point of Sleat to go to Portree, just as it is

an event for a Yorkshireman to go to London.

When you drive out of

Portree you are in Macleod’s country, and you discover that the

character of the scenery has changed. Looking back, the Cuchullins are

wild and pale on the horizon, but everything around is brown,

softly-swelling, and monotonous. The hills are round and low, and except

when an occasional boulder crops out on their sides like a wart, are

smooth as a seal’s back. They are gray

- green in colour, and may be grazed to the top. Expressing once to a

shepherd my admiration of the Cuchullins, the man replied, while he swept

with his arm the entire range, "There‘s no feeding there for twenty

wethers!" here, however, there is sufficient feeding to compensate

for any lack of beauty. About three miles out of Portree you come upon a

solitary-looking school-house by the wayside, and a few yards farther to a

division of the roads. A finger-post informs you that the road to the

right leads to Uig, that to the left to Dunvegan. As I am at present bound

for Dunvegan, I skirr along to the left, and after an hour’s drive come

in sight of blue Loch Snizort, with Skeabost sitting whitely on its

margin. Far inland from the broad Minch, like one of those wavering swords

which mediaeval painters place in the hands of archangels, has Snizort

come wandering; and it is the curious mixture of brine and pastureland, of

mariner life and shepherd life, which gives its charm to this portion of

the island. The Lochs are narrow, and you almost fancy a strong lunged man

could shout across. The sea-gull skims above the feeding sheep, the

shepherd can watch the sail of the sloop, laden with meal, creeping from

point to point. In the spiritual atmosphere of the

country the superstitions of ocean and moorland mingle like two odours.

Above all places which I have seen in Skye, Skeabost has a lowland look.

There are almost no turf-huts to be seen in the neighbourhood; the houses

are built of stone and lime, and are tidily white-washed. The hills are

low and smooth; on the lower slopes corn and wheat are grown; and from a

little distance the greenness of cultivation looks like a palpable smile—a

strange contrast to the monotonous district through which, for an hour or

so, you have driven. As you pass the inn, and drive across the bridge, you

notice that there is an island in the stony stream, and that this island

is covered with ruins. The Skye-man likes to bury his dead in islands, and

this one in the stream at Skeabost is a crowded cemetery. I forded the

stream, and wandered for an hour amongst the tombs and broken stones.

There are traces of an ancient chapel on the island, but tradition does

not even make a guess at its builder’s name or the date of its erection.

There are old slabs, lying sideways, with the figures of recumbent men

with swords in their hands, and inscriptions — indecipherable now—carved

on them. There is the grave of a Skye clergyman who, if his epitaph is to

be trusted, was a burning and a shining light in his day—a gospel candle

irradiating the Hebridean darkness. I never saw a churchyard so mounded,

and so evidently over-crowded. Here laird, tacksman, and cotter elbow each

other in death. Here no one will make way for a new-comer, or give the

wall to his neighbour. And standing in the little ruined island of silence

and the dead, with the river perfectly audible on either side, one could

not help thinking what a picturesque sight a Highland funeral would be,

creeping across the moors with wailing pipe-music, fording the river, and

his bearers making room for the dead man amongst the older dead as best

they could. And this sight, I am told, may be seen any week in the year.

To this island all the funerals of the country-side converge. Standing

there, too, one could not help thinking that this space of silence, girt

by river noises, would be an eerie place by moonlight. The broken

chapel, the carved slabs lying sideways, as if the dead man beneath had

grown restless and turned himself, and the head-stones jutting out of the

mounded soil at every variety of angle, would appal in the ink of shadow

and the silver of moonbeam. In such circumstances one would hear something

more in the stream as it ran past than the mere breaking of water on

stones.

After passing the river and the island

of graves you drive down

between hedges to Skeabost church, school, post-office, and manse, and

thereafter you climb the steep hill towards Bernesdale and its colony of

turf-huts; and when you reach the top you have a noble view of the flat

blue Minch, and the Skye headlands, each precipitous, abrupt, and

reminding you somehow of a horse which has been suddenly reined back to

its haunches. The flowing lines of those headlands suggest an onward

motion, and then, all at once, they shrink back upon themselves, as if

they feared the roar of breakers and the smell of the brine. But the grand

vision is not of long duration, for the road descends rapidly towards

Taynlone Inn. In my descent I beheld two bare-footed and bare-headed girls

yoked to a harrow, and dragging it up and down a small plot of delved

ground.

Sitting in the inn I began

to remember me how frequently I had heard in the south of the destitution

of the Skye people and the discomfort of the Skye hut. During my

wanderings I had the opportunity of visiting several of these dwellings,

and seeing how matters were transacted within. Frankly speaking, the

Highland hut is not a model edifice. It is open to wind, and almost always

pervious to rain. An old bottomless herring-firkin stuck in the roof

usually serves for chimney, but the blue peat-reek disdains that aperture,

and steams wilfully through the door and the crannies in the walls and

roof. The interior is seldom well-lighted —what light there is

proceeding rather from the orange glow of the peat-fire, on which a large

pot is simmering, than from the narrow pane with its great bottle-green

bull’s-eye. The rafters which support the roof are black and glossy with

soot, as you can notice by sudden flashes of firelight. The sleeping

accommodation is limited, and the beds are composed of heather or ferns.

The floor is the beaten earth, the furniture is scanty; there is hardly

ever a chair—stools and stones, worn smooth by the usage of several

generations, have to do instead. One portion of the hut is not

unfrequently a byre, and the breath of the cow is mixed with the odour of

peat-reek, and the baa of the calf mingles with the wranglings and

swift ejaculations of the infant Highlanders. In such a hut as this there

are sometimes three generations. The mother stands knitting outside, the

children are scrambling on the floor with the terrier and the poultry, and

a ray of cloudy sunshine from the narrow pane smites the silver hairs of

the grandfather near the fire, who is mending fishing-nets against the

return of his son-in-law from the south. Am I inclined to lift my hands in

horror at witnessing such a dwelling? Certainly

not. I have only given one side of the picture. The hut I speak of nestles

beneath a rock, on the top of which dances the ash-tree and the birch. The

emerald mosses on its roof are softer and richer than the velvets of

kings. Twenty yards down that path you will find a well that needs no ice

in the dog-days. At a little distance, from rocky shelf to shelf, trips a

mountain burn, with abundance of trout in the brown pools. At the distance

of a mile is the sea, which is not allowed to ebb and flow in vain; for in

the smoke there is a row of fishes drying; and on the floor a curly-headed

urchin of three years or thereby is pommeling the terrier with the scarlet

claw of a lobster. Methought, too, when I entered I saw beside the door a

heap of oyster shells. Within the hut there is good food, if a little

scant at times; without there is air that will call colour back to the

cheek of an invalid, pure water, play, exercise, work. That the people are

healthy, you may see from their strong frames, brown faces, and the age to

which many attain; that they are happy and light-hearted, the shouts of

laughter that ring round the peat-fire of an evening may be taken as

sufficient evidence. I protest I cannot become pathetic over the Highland

hut. I have sat in these turfen dwellings, amid the surgings of blue

smoke, and received hospitable welcome, and found amongst the inmates good

sense, industry, family affection, contentment, piety, happiness. And when

I have heard philanthropists, with more zeal than discretion, maintain

that these dwellings are a disgrace to the country in which they are

found, I have thought of districts of great cities which I have seen,—within

the sound of the rich man’s chariot wheels, within hearing of

multitudinous Sabbath bells—of evil scents and sights and sounds; of

windows stuffed with rags; of female faces that look out on you as out of

a sadder Inferno than that of Dante’s; of faces of men containing the de’bris

of the entire decalogue, faces which hurt you more than a blow would:

of infants poisoned with gin, of children bred for the prison and the

hulks. Depend upon it there are worse odours than peat smoke, worse

next-door neighbours than a cow or a brood of poultry; and although a

couple of girls dragging a harrow be hardly in accordance with our modern

notions, yet we need not forget that there are worse employment for girls

than even that. I do not stand up for the Highland hut; but in one of

these smoky cabins I would a thousand-fold rather spend my days than in

the Cowgate of Edinburgh, or in one of the streets that radiate from Seven

Dials.

After travelling three or

four days, I beheld on the other side of a long, blue, river-like loch,

the house of the Landlord. From the point at which I now paused, a boat

could have taken me across in half an hour, but as the road wound round

the top of the Loch, I had yet some eight or ten miles to drive before my

journey was accomplished. Meantime the Loch was at ebb and the sun was

setting. On the hill-side, on my left as I drove, stretched a long street

of huts covered with smoky wreaths, and in front of each a strip of

cultivated ground ran down to the road which skirted the shore. Potatoes

grew in one strip or lot, turnips in a second, corn in a third, and as

these crops were in different stages of advancement, the entire hill-side,

from the street of huts downward, resembled one of those counterpanes

which thrifty housewifes manufacture by sewing together patches of

different patterns. Along the road running at the back of the huts a cart

was passing; on the moory hill behind, a flock of sheep, driven by men and

dogs, was contracting and expanding itself like quicksilver. The women

were knitting at the hut doors, the men were at work in the cultivated

patches in front. On all this scene of cheerful and fortunate industry, on

men and women, on turnips, oats, and potatoes, on cottages set in azure

films of peat-reek, the rosy light was striking— making a pretty

spectacle enough. From the whole hill-side breathed peace, contentment,

happiness, and a certain sober beauty of usefulness. Man and nature seemed

in perfect agreement and harmony—man willing to labour, nature to yield

increase. Down to the head of the Loch the road sloped rapidly, and at the

very head a small village had established itself. It contained an inn, a

school-house, in which divine service was held on Sundays; a smithy, a

merchant’s shop—all traders are called merchants in Skye—and,

by the side of a stream which came brawling down from rocky steep to

steep, stood a corn mill, the big wheel lost in a watery mist of its own

raising, the door and windows dusty with meal. Behind the village lay a

stretch of black moorland intersected by drains and trenches, and from the

black huts which seemed to have grown out of the moor, and the spaces of

sickly green here and there, one could see that the desolate and

forbidding region had its colonists, and that they were valiantly

attempting to wring a sustenance out of it. Who were the squatters on the

black moorland? Had they accepted their hard conditions as a matter of

choice, or had they been banished there by a superior power? Did the

dweller in those outlying huts bear the same relation to the villagers, or

the flourishing cotters on the hill-side, that the gipsy bears to the

English peasant, or the red Indian to the Canadian farmer? I had no one to

inform me at the time; meanwhile the sunset fell on these remote

dwellings, lending them what beauty and amelioration of colour it could,

making a drain sparkle for a moment, turning a far-off pool into gold

leaf, and rendering, by contrast of universal warmth and glow, yet more

beautiful the smoke which swathed the houses. Yet after all the impression

made upon one was cheerless enough. Sunset goes but a little way in

obviating human wretchedness. It fires the cottage window, but it cannot

call to life the corpse within; it can sparkle on the chain of a prisoner,

but with all its sparkling it does not make the chain one whit the

lighter. Misery is often picturesque, but the picturesqueness is in the

eyes of others, not in her own. The black moorland and the banished huts

abode in my mind during the remainder of my drive.

Everything about a man is

characteristic, more or less; and in the house of the Landlord I found

that singular mixture of hemispheres which I had before noticed in his

talk and in his way of looking at times. His house was plain enough

externally, but its furniture was curious and far-brought. The interior of

his porch was adorned with heads of stags and tusks of elephants. He would

show you Highland relics, and curiosities from sacked Eastern palaces. He

had the tiny porcelain cup out of which Prince Charles drank tea at

Kingsburgh, and the signet ring which was stripped from the dead fingers

of Tippoo Saib. In his gun-room were modern breech-loaders and revolvers,

and matchlocks from China and Nepaul. On the walls were Lochaber axes,

claymores, and targets that might have seen service at Inverlochy, hideous

creases, Afghan daggers, curiously-curved swords, scabbards thickly

crusted with gems. In the library the last new novel leaned against the

"Institutes of Menu." On the drawing-room table, beside

carte-de-visite books, were ivory card-cases wrought by the patient Hindoo artificer

as finely as we work our laces, Chinese puzzles that baffled all European

comprehension, and comical squabfaced deities in silver and bronze. While

the Landlord was absent, I could fancy these strangely assorted articles

striking one with a sense of incongruity: but when at home, each seemed a

portion of himself. He was related as closely to the Indian god as to

Prince Charles’s cup. The ash and birch of the Highlands danced before

his eyes, the palm stood in his imagination and memory.

And then he surrounded

himself with all kinds of pets, and lived with them on the most intimate

terms. When he entered the breakfast-room his terriers barked and frisked

and jumped about him; his great black hare-hound, Maida, got up from the

rug on which it had been basking and thrust its sharp nose into his hand;

his canaries broke into emulous music, as if sunshine had come into the

room; the parrot in the porch clambered along the cage with horny claws,

settled itself on its perch, bobbed its head up and down for a moment, and

was seized with hooping-cough. When he went out the black hare-hound

followed at his heel; the peacock, strutting on the gravel in the shelter

of the larches, unfurled its starry fan; in the stable his horses turned

round to smell his clothes and to have their foreheads stroked: melodious

thunder broke from the dog-kennel when he came: and at his approach his

falcons did not withdraw haughtily, as if in human presence there was

profanation; they listened to his voice, and a gentler something tamed for

a moment the fierce cairngorms of their eyes. When others came near they

ruffled their plumage and uttered sharp cries of anger.

After breakfast it was his

habit to carry the parrot out to a long iron garden-seat in front of the

house—where, if sunshine was to be had at all, you were certain to find

it—and placing the cage beside him, smoke a cheroot. The parrot would

clamber about the cage, suspended head downwards would take crafty stock

of you with an eye which had perhaps looked out on the world for a century

or so, and then, righting itself, peremptorily insist that Polly should

put on the kettle, and that the boy should shut up the grog. On one

special morning, while the Landlord was smoking and the parrot whooping

and whistling, several men, dressed in rough pilot cloth which had seen

much service and known much darning, came along the walk and respectfully

uncovered. Returning their salutation, the Landlord threw away the end of

his cheroot and went forward to learn their message. The conversation was

in Gaelic: slow and gradual at first, it quickened anon, and broke into

gusts of altercation; and on these occasions I noticed that the Landlord

would turn impatiently on his heel, march a pace or two back to the house,

and then, wheeling round, return to the charge. He argued in the unknown

tongue, gesticulated, was evidently impressing something on his auditors

which they were unwilling to receive, for at intervals they would look in

one another’s faces,—a look plainly implying, "Did you ever hear

the like ?" and give utterance to a murmured chit, chit, chit of

dissent and humble protestation. At last the matter got itself amicably

settled, the deputation—each man making a short sudden duck before

putting on his bonnet—withdrew, and the Landlord came back to the

parrot, which had, now with one eye, now with another, been watching the

proceeding. He sat down with a slight air of annoyance.

"These fellows are

wanting more meal," he said, "and one or two are pretty deep in

my books already."

"Do you, then, keep

regular accounts with them ?"

"Of course. I give

nothing for nothing. I wish to do them as much good as I can. They are a

good deal like my old ryots, only the ryot was more supple and

obsequious."

"Where do your friends

come from ?" I asked. "From the village over there,"

pointing across the narrow blue loch. "Pretty Polly! Polly!"

The parrot was climbing up

and down the cage, taking hold of the wires with beak and claw as it did

so.

"I wish to know

something of your villagers. The cotters on the hill-side seem comfortable

enough, but I wish to know something of the black land and the lonely huts

behind."

"Oh," said he,

laughing, "that is my penal settlement - I'll drive you over

tomorrow." He then got up, tossed a stone into the shrubbery, after

which Maida dashed, thrust his hands into his breeches' pocket for a

moment, and marched into the house.

Next morning we drove

across to the village, and pretty enough it looked as we alighted. The big

water-wheel of the mill whirred industrious music, flour flying about the

door and windows. Two or three people were standing at the merchant’s

shop. At the smithy a horse was haltered, and within were brilliant

showers of sparks and the merry clink of hammers. The sunshine made pure

amber the pools of the tumbling burn, and in one of these a girl was

rinsing linen, the light touching her hair into a richer colour. Our

arrival at the inn created some little stir. The dusty miller came out,

the smith came to the door rubbing down his apron with a horny palm, the

girl stood upright by the burn-side shading her eyes with her hand, one of

the men at the merchant’s shop went within to tell the news, the

labourers in the fields round about stopped work to stare.

The machine was no sooner

put to rights and the horses taken round to the stable than the mistress

of the house complained that the roof was leaky, and she and the Landlord

went in to inspect the same. Left alone for a little, I could observe

that, seeing my friend had arrived, the people were resolved to make some

use of him, and here and there I noticed them laying down their crooked

spades, and coming down towards the inn. One old woman, with a white

handkerchief tied round her head, sat down on a stone opposite, and when

the Landlord appeared—the matter of the leaky roof having been arranged—she

rose and dropped courtesy. She had a complaint to make, a benefit to ask,

a wrong to be redressed. I could not, of course, understand a word of the

conversation, but curiously sharp and querulous was her voice, with a

slight suspicion of the whine of the mendicant in it, and every now and

then she would give a deep sigh, and smooth down her apron with both her

hands. I suspect the old lady gained her object, for when the Landlord

cracked his joke at parting the most curious sunshine of merriment came

into the withered features, lighting them up and changing them, and giving

one, for a flying second, some idea of what she must have been in her

middle age, perhaps in her early youth, when she as well as other girls

had a sweetheart.

In turn we visited the

merchant’s shop, the smithy, and the mill; then we passed the

schoolhouse—which was one confused murmur, the sharp voice of the

teacher striking through at intervals—and turning up a narrow road, came

upon the black region and the banished huts. The cultivated hill-side was

shining in sunlight, the cottages smoking, the people at work in their

crofts—everything looking blithe and pleasant; and under the bright sky

and the happy weather the penal settlement did not look nearly so

forbidding as it had done when, under the sunset, I had seen it a few

evenings previously. The houses were rude, but they seemed sufficiently

weather-tight. Each was set down in a little oasis of cultivation, a

little circle in which by labour the sour land had been coaxed into a

smile of green; each small domain was enclosed by a low turfen wall, and

on the top of one of these a wild goat-looking sheep was feeding, which,

as we approached, jumped down with an alarmed bleat, and then turned to

gaze on the intruders. The land was sour and stony, the dwellings framed

of the rudest materials, and the people—for they all came forward to

meet him, and at each turfen wall the Landlord held a levée—especially

the older people, gave one the idea somehow of worn-out tools. In some

obscure way they reminded one of bent and warped oars, battered spades,

blunted pickaxes. On every figure was written hard, unremitting toil. Toil

had twisted their frames, seamed and puckered their leathern faces, made

their hands horny, bleached their grizzled locks. Your fancy had to run

back along years and years of labour before it could arrive at the

original boy or girl. Still they were cheerful-looking after a sort,

contented, and loquacious withal. The man took off his bonnet, the woman

dropped her courtesy, before pouring into the Landlord’s ear how the

wall of the house wanted mending, how a neighbour’s sheep had come into

the corn, had been driven into the corn out of foul spite and envy it was

suspected, how new seed would be required for next year’s sowing, how

the six missing fleeces had been found in the hut of the old soldier

across the river, and all the other items which made up their world. And

the Landlord, his black hound couched at his feet, would sit down on a

stone, or lean against the turf wall and listen to the whole of it, and

consult as to the best way to repair the decaying house, and discover how

defendant’s sheep came into complainant’s corn, and give judgment, and

promise new seed to old Donald, and walk over to the soldier’s and pluck

the heart out of the mystery of the missing fleeces. And going in and out

amongst his people, his functions were manifold. He was not Landlord only—he

was leech, lawyer, divine. He prescribed medicine, he set broken bones,

and tied up sprained ankles; he was umpire in a hundred petty quarrels,

and damped out wherever he went every flame of wrath. Nor, when it was

needed, was he without ghostly counsel. On his land he would permit no

unbaptized child; if Donald was drunk and brawling at a fair, he would,

when the inevitable headache and nausea were gone, drop in and improve the

occasion, to Donald’s much discomfiture and his many blushes; and with

the bed-ridden woman, or the palsied man, who for years had sat in the

corner of the hut as constantly as a statue sits within its niche—just

where the motty sunbeam from the pane with its great knob of bottle-green

struck him—he held serious conversations, and uttered words which come

usually from the lips of a clergyman.

We then went through the

cottages on the cultivated hill-side, and there another series of levées

were held. One cotter complained that his neighbour had taken advantage of

him in this or the other matter: another man’s good name had been

aspersed by a scandalous tongue, and ample apology must be made, else the

sufferer would bring the asperser before the sheriff. Norman had borrowed

for a day Neil’s plough, had broken the shaft, and when requested to

make reparation, had refused in terms too opprobrious to be repeated. The

man from Sleat who had a year or two ago come to reside in these parts,

and with whom the world had gone prosperously, was minded at next fair to

buy another cow—would he therefore be allowed to rent the croft which

lay alongside the one which he already possessed? To these cotters the

Landlord gave attentive ear, standing beside the turf dike, leaning

against the walls of their houses, sitting down inside in the peat smoke—the

children gathered together in the farthest corner, and regarding him with

no little awe. And so he came to know all the affairs of his people—who

was in debt, who was waging a doubtful battle with the world, who had

money in the bank; and going daily amongst them he was continually engaged

in warning, expostulation, encouragement, rebuke. Nor was he always

sunshine: he was occasionally lightning too. The tropical tornado, which

unroofs houses and splits trees, was within the possibilities of his moods

as well as the soft wind which caresses the newly-yeaned lamb. Against

greed, laziness, dishonesty, he flamed like a seven-times heated furnace.

When he found that argument had no effect on the obstinate or the

pig-headed, he suddenly changed his tactics, and descended in a shower of

chaff which is to the Gael an unknown and terrible power, dissolving

opposition as salt dissolves a snail.

The last cotter had been

seen, the last levée had been held, and we then climbed up to the crown

of the hill to visit the traces of an old fortification, or dun, as the

Skye people call it. These ruins, and they are thickly scattered over the

island, are supposed to be of immense antiquity—so old, that Ossian may

have sung in each to a circle of Fingalian chiefs. When we reached the dun—a

loose congregation of mighty stones, scattered in a circular form, with

some rude remnants of an entrance and a covered way—we sat down, and the

Landlord lighted a cheroot. Beneath lay the little village covered with

smoke. Far away to the right, Skye stretched into ocean, pale headland

after headland. In front, over a black wilderness of moor, rose the

conical forms of Macleod’s Tables, and one thought of the "restless

bright Atlantic plain" beyond, the endless swell and shimmer of

watery ridges, the clouds of sea birds, the sudden glistening upheaval of

a whale and its disappearance, the smoky trail of a steamer on the

horizon, the tacking of white-sailed craft. On the left, there was nothing

but moory wilderness and hill, with something on a slope flashing in the

sunshine like a diamond. A falcon palpitating in the intense blue above,

the hare-hound cocked her ears and looked out alertly, the Landlord with

his field-glass counted the sheep feeding on the hill-side a couple of

miles off. Suddenly he closed the glass, and lay back on the heather,

puffing a column of white smoke into the air.

"I suppose," said

I, "your going in and out amongst your tenants to-day is very much

the kind of thing you used to do in India ?"

"Exactly. I know these

fellows, every man of them—and they know me. We get on very well

together. I know everything they do. I know all their secrets, all their

family histories, everything they wish, and everything they fear. I think

I have done them some good since I came amongst them."

"But," said I,

"I wish you to explain to me your system of penal servitude, as you

call it In what respect do the people on the cultivated hillside differ

from the people in the black ground behind the village?"

"Willingly. But I must

premise that the giving away of money in charity is, in nine cases out of

ten, tantamount to throwing money into the fire. It does no good to the

bestower: it does absolute harm to the receiver. You see I have taken the

management of these people into my own hands. I have built a school-house

for them—on which we will look in and overhaul on our way down—I have

built a shop, as you see, a smithy, and a mill. I have done everything for

them, and I insist that, when a man becomes my tenant, he shall pay me

rent. If I did not so insist I should be doing an injury to myself and to

him. The people on the hill-side pay me rent; not a man Jack of them is at

this moment one farthing in arrears. The people down there in the black

land behind the village, which I am anxious to reclaim, don’t pay rent

They are broken men, broken sometimes by their own fault and laziness,

sometimes by culpable imprudence, sometimes by stress of circumstances.

When I settle a man there I build him a house, make him a present of a bit

of land, give him tools, should he require them, and set him to work. He

has the entire control of all he can produce. He improves my land, and

can, if he is industrious, make a comfortable living. I won’t have a

pauper on my place: the very sight of a pauper sickens me."

"But why do you call

the black lands your penal settlement?"

Here the Landlord laughed.

"Because, should any of the crofters on the hill-side, either from

laziness or misconduct, fall into arrears, I transport him at once. I

punish him by sending him among the people who pay no rent. It’s like

taking the stripes off a sergeant’s arm and degrading him to the ranks;

and if there is any spirit in the man he tries to regain his old position.

I wish my people to respect themselves, and to hold poverty in

horror."

"And do many get back

to the hill- side again ?" "Oh, yes! and they are all the better

for their temporary banishment. I don’t wish residence there to be

permanent in any case. When one of these fellows gets on, makes a little

money, I have him up here at once among the rent-paying people. I draw the

line at a cow."

"How?"

"When a man by

industry or by self-denial has saved money enough to buy a cow, I consider

the black land is no longer the place for him. He is able to pay rent, and

he must pay it. I brought an old fellow up here the other week, and very

unwilling he was to come. He had bought himself a cow, and so I marched

him up here at once. I wish to stir all these fellows up, to put into them

a little honest pride and self-respect"

"And how do they take

to your system?"

"Oh, they grumbled a

good deal at first, and thought their lines were hard; but discovering

that my schemes have been for their benefit, they are content enough now.

In these black lands, you observe, I not only rear corn and potatoes, I

rear and train men, which is the most valuable crop of all. But let us be

going. I wish you to see my scholars. I think I have got one or two smart

lads down there."

In a short time we reached

the school-house, a plain, substantial-looking building, standing midway

between the inn and the banished huts. As it was arranged that neither

schoolmaster nor scholar should have the slightest idea that they were to

be visited that day, we were enabled to see the school in its ordinary

aspect. When we entered the master came forward and shook hands with the

Landlord, the boys pulled their red fore-locks, the girls dropped their

best courtesies. Sitting down on a form I noted the bare walls, a large

map hanging on one side, the stove with a heap of peats near it, the

ink-smeared bench and the row of girls’ heads, black, red, yellow, and

brown, surmounting it, and the boys, barefooted and in tattered kilts,

gathered near the window. The girls regarded us with a shy, curious gaze,

which was not ungraceful; and in several of the freckled faces there was

the rudiments of beauty, or of comeliness at least. The eyes of all, boys

as well as girls, kept twinkling over our persons, taking silent note of

everything. I don’t think I ever before was the subject of so much

curiosity. One was pricked all over by quick-glancing eyes as by pins. We

had come to examine the school, and the ball opened by a display of copy

books. Opening these, we found pages covered with "Emulation is a

generous passion," "Emancipation does not make man," in

very fair and legible handwriting. Expressing our satisfaction, the

schoolmaster bowed low, and the prickling of the thirty or forty curious

eyes became yet more keen and rapid. The schoolmaster then called for

those who wished to be examined in geography—very much as a colonel

might seek volunteers for a forlorn hope—and in a trice six scholars,

kilted, of various ages and sizes, but all shock-headed and ardent, were

drawn up in line in front of the large map. A ruler was placed in the hand

of a little fellow at the end, who, with his eyes fixed on the

schoolmaster and his body bent forward eagerly, seemed as waiting the

signal to start off in a race. "Number one, point out river Tagus."

Number one charged the Peninsula with his ruler as ardently as his

great-grandfather in all probability charged the French at Quebec.

"Through what country does the Tagus flow ?" "PortugaL"

"What is the name of the capital city ?" "Lisbon."

Number one having accomplished his devoir, the ruler was handed on to

number two, who traced the course of the Danube, and answered several

questions thereanent with considerable intelligence. Number five was a

little fellow; he was asked to point out Portree, and as the Western

Islands hung too high in the north for him to reach, he jumped at them. He