|

SUMMER has leaped suddenly on Edinburgh like a tiger.

The air is still and hot above the houses; but every now and then a

breath of east wind startles you through the warm sunshine—like a

sudden sarcasm felt through a strain of flattery—and passes on

detested of every organism. But, with this exception, the atmosphere is

so close, so laden with a body of heat, that a thunderstorm would be

almost welcomed as a relief. Edinburgh, on her crags, held high towards

the sun—too distant the sea to send cool breezes to street and square—is

at this moment an uncomfortable dwelling-place. Beautiful as ever, of

course—for nothing can be finer than the ridge of the Old Town etched

on hot summer azure— but close, breathless, suffocating. Great volumes

of white smoke surge out of the railway station; great choking puffs of

dust issue from the houses and shops that are being gutted in Princes

Street. The Castle rock is gray; the trees are of a dingy olive; languid

"swells," arm-in-arm, promenade uneasily the heated pavement;

water-carts everywhere dispense their treasures; and the only human

being really to be envied in the city is the small boy who, with

trousers tucked up, and unheeding of maternal vengeance, marches coolly

in the fringe of the ambulating shower-bath. Oh for one hour of heavy

rain! Thereafter would the heavens wear a clear and tender, instead of a

dim and sultry hue. Then would the Castle rock brighten in colour, and

the trees and grassy slopes doff their dingy olives for the emeralds of

April. Then would the streets be cooled, and the dust be allayed. Then

would the belts of city verdure, refreshed, pour forth gratitude in

balmy smells; and Fife—low-lying across the Forth—break from its hot

neutral tint into the greens, purples, and yellows that of right belong

to it. But rain won’t come; and for weeks, perhaps, there will be

nothing but hot sun above, and hot street beneath; and for the

respiration of poor human lungs an atmosphere of heated dust, tempered

with east wind.

Moreover, one is tired and jaded. The whole man, body

and soul, like sweet bells jangled, out of tune, and harsh, is fagged

with work, eaten up of impatience, and haunted with visions of vacation.

One "babbles o’ green fields," like a very Falstaff; and the

poor tired ears hum with sea-music like a couple of sea-shells. At last

it comes, the 1st of August, and then—like an arrow from a Tartar’s

bow, like a bird from its cage, like a lover to his mistress—one is

off; and before the wild scarlets of sunset die on the northern sea, one

is in the silence of the hills, those eternal sun-dials that tell the

hours to the shepherd, and in one’s nostrils is the smell of

peat-reek, and in one’s throat the flavour of usquebaugh. Then come

long floating summer days, so silent the wilderness, that one can hear

one’s heart beat; then come long silent nights, the waves heard upon

the shore, although that is a mile away, in which one snatches

the "fearful joy" of a ghost story, told by shepherd or

fisher, who believes in it as in his own existence. Then one beholds

sunset, not through the smoked glass of towns, but gloriously through

the clearness of enkindled air. Then one makes acquaintance with

sunrise, which to the dweller in a city, who conforms to the usual

proprieties, is about the rarest of this world’s sights.

Mr

De Quincey maintains, in one of his essays, that dinner—dinner about

seven in the evening, for which one dresses, which creeps on with

multitudinous courses and entrées, which, so far from being a gross

satisfaction of appetite, is a feast noble, graceful, adorned with the

presence and smile of beauty, and which, from the very stateliness of

its progress, gives opportunities for conversation and the encounter of

polished minds—saves over-wrought London from insanity. This is no

mere humorous exaggeration, but a very truth; and what dinner is to the

day the Highlands are to the year. Away in the north, amid its green or

stony silences, jaded hand and brain find repose—repose, the depth and

intensity of which the idler can never know. In that blessed idleness

you become in a strange way acquainted with yourself; for in the world

you are too constantly occupied to spend much time in your own company.

You live abroad all day, as it were, and only come home to sleep. Away

in the north you have nothing else to do, and cannot quite help

yourself; and conscience, who has kept open a watchful eye, although her

lips have been sealed these many months, gets disagreeably

communicative, and tells her mind pretty freely about certain little

shabby selfishnesses and unmanly violences of temper, which you had

quietly consigned — like a document which you were for ever done with

— to the waste-basket of forgetfulness. And the quiet, the silence,

the rest, is not only good for the soul, it is good for the body too.

You flourish like a flower in the open air; the hurried pulse beats a

wholesome measure; evil dreams roll off your slumbers; indigestion dies.

During your two months’ vacation, you amass a fund of superfluous

health, and can draw on it during the ten months that succeed. And in

going to the north, and wandering about the north, it is best to take

everything quietly and in moderation. It is better to read one good book

leisurely, lingering over the finer passages, returning frequently on an

exquisite sentence, closing the volume, now and then, to run down in

your own mind a new thought started by its perusal, than to rush in a

swift perfunctory manner through half a library. It is better to sit

down to dinner in a moderate frame of mind, to please the palate as well

as satisfy the appetite, to educe the sweet juices of meats by

sufficient mastication, to make your glass of port "a linked

sweetness long drawn out," than to bolt everything like a

leathern-faced Yankee for whom the cars are waiting, and who fears that

before he has had his money’s worth, he will be summoned by the

railway bell.. And shall one, who wishes to extract from the world as

much enjoyment as his nature will allow him, treat the Highlands less

respectfully than he will his dinner? So at least will not I. My bourne

is the island of which Douglas dreamed on the morning of Otterburn; but

even to it I will not unnecessarily hurry, but will look on many

places on my way. You have to go to London; but unless your business is

urgent, you are a fool to go thither like a parcel in the night train

and miss York and Peterborough. It is very fine to arrive at majority,

and the management of your fortune which has been all the while

accumulating for years; but you do not wish to do so at a sudden leap—to

miss the April eyes and April heart of seventeen! Mr

De Quincey maintains, in one of his essays, that dinner—dinner about

seven in the evening, for which one dresses, which creeps on with

multitudinous courses and entrées, which, so far from being a gross

satisfaction of appetite, is a feast noble, graceful, adorned with the

presence and smile of beauty, and which, from the very stateliness of

its progress, gives opportunities for conversation and the encounter of

polished minds—saves over-wrought London from insanity. This is no

mere humorous exaggeration, but a very truth; and what dinner is to the

day the Highlands are to the year. Away in the north, amid its green or

stony silences, jaded hand and brain find repose—repose, the depth and

intensity of which the idler can never know. In that blessed idleness

you become in a strange way acquainted with yourself; for in the world

you are too constantly occupied to spend much time in your own company.

You live abroad all day, as it were, and only come home to sleep. Away

in the north you have nothing else to do, and cannot quite help

yourself; and conscience, who has kept open a watchful eye, although her

lips have been sealed these many months, gets disagreeably

communicative, and tells her mind pretty freely about certain little

shabby selfishnesses and unmanly violences of temper, which you had

quietly consigned — like a document which you were for ever done with

— to the waste-basket of forgetfulness. And the quiet, the silence,

the rest, is not only good for the soul, it is good for the body too.

You flourish like a flower in the open air; the hurried pulse beats a

wholesome measure; evil dreams roll off your slumbers; indigestion dies.

During your two months’ vacation, you amass a fund of superfluous

health, and can draw on it during the ten months that succeed. And in

going to the north, and wandering about the north, it is best to take

everything quietly and in moderation. It is better to read one good book

leisurely, lingering over the finer passages, returning frequently on an

exquisite sentence, closing the volume, now and then, to run down in

your own mind a new thought started by its perusal, than to rush in a

swift perfunctory manner through half a library. It is better to sit

down to dinner in a moderate frame of mind, to please the palate as well

as satisfy the appetite, to educe the sweet juices of meats by

sufficient mastication, to make your glass of port "a linked

sweetness long drawn out," than to bolt everything like a

leathern-faced Yankee for whom the cars are waiting, and who fears that

before he has had his money’s worth, he will be summoned by the

railway bell.. And shall one, who wishes to extract from the world as

much enjoyment as his nature will allow him, treat the Highlands less

respectfully than he will his dinner? So at least will not I. My bourne

is the island of which Douglas dreamed on the morning of Otterburn; but

even to it I will not unnecessarily hurry, but will look on many

places on my way. You have to go to London; but unless your business is

urgent, you are a fool to go thither like a parcel in the night train

and miss York and Peterborough. It is very fine to arrive at majority,

and the management of your fortune which has been all the while

accumulating for years; but you do not wish to do so at a sudden leap—to

miss the April eyes and April heart of seventeen!

The Highlands can be

enjoyed in the utmost simplicity; and the best preparations are—money

to a moderate extent in one’s pocket, a knapsack containing a spare

shirt and a toothbrush, and a courage that does not fear to breast the

steep of the hill, and to encounter the pelting of a Highland shower. No

man knows a country till he has walked through it; he then tastes the

sweets and the bitters of it. He beholds its grand and important points,

and all the subtler and concealed beauties that lie out of the beaten

track. Then, O reader, in the most glorious of the months, the very

crown and summit of the fruitful year, hanging in equal poise between

summer and autumn, leave London or Edinburgh, or whatever city your lot

may happen to be cast in, and accompany me on my wanderings. Our course

will lead us by ancient battle-fields, by castles standing in hearing of

the surge; by the bases of mighty mountains, along the wanderings of

hollow glens; and if the weather holds, we may see the keen ridges of

Blaavin and the Cuchullin hills; listen to a legend old as Ossian, while

sitting on the broken stair of the castle of Duntulm, beaten for

centuries by the salt flake and the wind; and in the pauses of ghostly

talk in the long autumn nights, when the rain is on the hills, we may

hear—more wonderful than any legend, carrying you away to misty

regions and half-forgotten times—the music which haunted the

Berserkers of old, the thunder of the northern sea!

A perfect library of

books has been written about Edinburgh. Defoe, in his own

matter-of-fact, garrulous way, has described the city. Its towering

streets, and the follies of its society, are reflected in the inimitable

pages of "Humphrey Clinker." Certain aspects of city

life, city amusements, city dissipations, are mirrored in the clear,

although somewhat shallow, stream of Fergusson’s humour. The old life

of the place, the traffic in the streets, the old-fashioned shops, the

citizens with cocked hats and powdered hair, with hospitable paunches

and double chins, with no end of wrinkles, and hints of latent humour in

their worldly - wise faces, with gold-headed sticks, and shapely limbs

encased in close-fitting small-clothes, are found in "Kay’s

Portraits." Passing Scott’s other services to the city—the

magnificent description in "Marmion," the "high

jinks" in "Guy Mannering," the broils of the nobles and

wild chieftains who attended the Court of the Jameses in "The

Abbot"—he has, in "The Heart of Mid-Lothian," made

immortal many of the city localities; and the central character of

Jeanie Deans is so unassumingly and sweetly Scotch, that she

seems as much a portion of the place as Holyrood, the Castle, or the

Crags. In Lockhart’s "Peter’s Letters to his Kinsfolk," we

have sketches of society nearer our own time, when the Edinburgh

Review flourished, when the city was really the Modern Athens, and a

seat of criticism giving laws to the empire. In these pages, we are

introduced to Jeffrey, to John Wilson, the Ettrick Shepherd, and Dr

Chalmers. Then came Blackwood’s Magazine, the "Chaldee

Manuscript," the "Noctes," and "Margaret

Lindsay." Then the "Traditions of Edinburgh," by Mr

Robert Chambers; thereafter the well-known Edinburgh Journal. Since

then we have had Lord Cockburn’s chatty "Memorials of his

Time." Almost the other day we had Dean Ramsay’s Lectures, filled

with pleasant antiquarianism, and information relative to the men and

women who flourished half a century ago. And the list may be closed with

"Edinburgh Dissected," written after the fashion of Lockhart’s

"Letters,"—a book containing pleasant reading enough,

although it wants the brilliancy, the acuteness, the eloquence, and

possesses all the ill-nature, of its famous prototype.

Scott has done more for Edinburgh than all her great

men put together. Burns has hardly left a trace of himself in the

northern capital. During his residence there his spirit was soured, and

he was taught to drink whisky-punch—obligations which he repaid by

addressing "Edina, Scotia’s darling seat," in a copy of his

tamest verses. Scott discovered that the city was beautiful—he sang

its praises over the world—and he has put more coin into the pockets

of its inhabitants than if he had established

a branch of manufacture of which they had the monopoly. Scott’s novels

were to Edinburgh what the tobacco trade was to Glasgow about the close

of the last century. Although several labourers were before him in the

field of the Border Ballads, he made fashionable those wonderful stories

of humour and pathos. As soon as "The Lay of the Last

Minstrel" appeared, everybody was raving about Melrose and

moonlight. He wrote "The Lady of the Lake," and next year a

thousand tourists descended on the Trosachs, watched the sun setting on

Loch Katrine, and began to take lessons on the bagpipe. He improved the

Highlands as much as General Wade did when he struck through them his

military roads. Where his muse was one year, a mail-coach and a hotel

were the next. His poems are grated down into guidebooks. Never was an

author so popular as Scott, and never was popularity worn so lightly and

gracefully. In his own heart he did not value it highly; and he cared

more for his plantations at Abbotsford than for his poems and novels. He

would rather have been praised by Tom Purdie than by any critic. He was

a great, simple, sincere, warm-hearted man. He never turned aside from

his fellows in gloomy scorn; his lip never curled with a fine disdain.

He never ground his teeth save when in the agonies of toothache. He

liked society, his friends, his dogs, his domestics, his trees, his

historical nick-nacks. At Abbotsford, he would write a chapter of a

novel before his guests were out of bed, spend the day with them, and

then, at dinner, with his store of shrewd Scottish anecdote, brighten

the table more than did the champagne. When in Edinburgh, any one might

see him in the streets or in the Parliament House. He was loved by

everybody. No one so popular among the souters of Selkirk as the Shirra.

George IV., on his visit to the northern kingdom, declared that

Scott was the man he most wished to see. He was the deepest, simplest,

man of his time. The mass of his greatness takes away from our sense of

its height. He sinks like Ben Cruachan, shoulder after shoulder, slowly,

till its base is twenty miles in girth. Scotland is Scott-land. He is

the light in which it is seen. He has proclaimed over all the world

Scottish story, Scottish humour, Scottish feeling, Scottish virtue; and

he has put money into the pockets of Scottish hotel-keepers, Scottish

tailors, Scottish boatmen, and the drivers of the Highland mails.

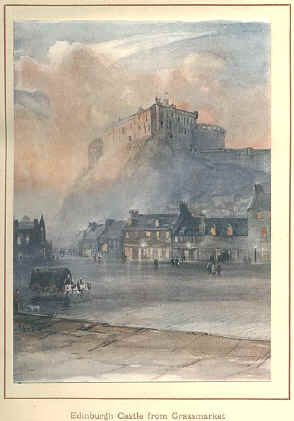

Every

true Scotsman believes Edinburgh to be the most picturesque city in the

world; and truly, standing on the Calton Hill at early morning, when the

smoke of fires newly-kindled hangs in azure swathes and veils about the

Old Town—which from that point resembles a huge lizard, the Castle its

head, church-spires spikes upon its scaly back, creeping up from its

lair beneath the Crags to look out on the morning world—one is quite

inclined to pardon the enthusiasm of the North Briton. The finest view

from the interior is obtained from the corner of St Andrew Street,

looking west. Straight before you the Mound crosses the valley, bearing

the white Academy buildings; beyond, the Castle lifts, from grassy

slopes and billows of summer foliage, its weather-stained towers and

fortifications, the Half-Moon battery giving the folds of its standard

to the wind. Living in Edinburgh there abides, above all things, a sense

of its beauty. Hill, crag, castle, rock, blue stretch of sea, the

picturesque ridge of the Old Town, the squares and terraces of the New—

these things seen once are not to be forgotten. The quick life of to-day

sounding around the relics of antiquity, and overshadowed by the august

traditions of a kingdom, makes residence in Edinburgh more impressive

than residence in any other British city. I have just come in—surely

it never looked so fair before? What a poem is that Princes Street! The

puppets of the busy, many-coloured hour move about on its pavement,

while across the ravine Time has piled up the Old Town, ridge on ridge,

gray as a rocky coast washed and worn by the foam of centuries; peaked

and jagged by gable and roof; windowed from basement to cope; the whole

surmounted by St Giles’s airy crown. The New is there looking at the

Old. Two Times are brought face to face, and are yet separated by a

thousand years. Wonderful on winter nights, when the gully is filled

with darkness, and out of it rises, against the sombre blue and the

frosty stars, that mass and bulwark of gloom, pierced and quivering with

innumerable lights. There is nothing in Europe to match that, I think.

Could you but roll a river down the valley it would be sublime. Finer

still, to place one’s-self near the Burns Monument and look toward the

Castle. It is more astonishing than an Eastern dream. A city rises up

before you painted by fire on night. High in air a bridge of lights

leaps the chasm; a few emerald lamps, like glow-worms, are moving

silently about in the railway station below; a solitary crimson one is

at rest. That ridged and chimneyed bulk of blackness, with splendour

bursting out at every pore, is the wonderful Old Town,

where Scottish history mainly transacted itself; while, opposite, the

modern Princes Street is blazing throughout its length. During the day

the Castle looks down upon the city as if out of another world; stern

with all its peacefulness, its garniture of trees, its slopes of grass.

The rock is dingy enough in colour, but after a shower, its lichens

laugh out greenly in the returning sun, while the rainbow is brightening

on the lowering sky beyond. How deep the shadow which the Castle throws

at noon over the gardens at its feet where the children play! How grand

when giant bulk and towery crown blacken against sunset! Fair, too, the

New Town sloping to the sea. From George Street which crowns the ridge,

the eye is led down sweeping streets of stately architecture to the

villas and woods that fill the lower ground, and fringe the shore; to

the bright azure belt of the Forth with its smoking steamer or its

creeping sail; beyond, to the shores of Fife, soft blue, and flecked

with fleeting shadows in the keen clear light of spring, dark purple in

the summer heat, tarnished gold in the autumn haze; and farther away

still, just distinguishable on the paler sky, the crest of some distant

peak, carrying the imagination into the illimitable world. Residence

in Edinburgh is an education in itself. Its beauty refines one like

being in love. It is perennial, like a play of Shakespeare’s. Nothing

can stale its infinite variety. Every

true Scotsman believes Edinburgh to be the most picturesque city in the

world; and truly, standing on the Calton Hill at early morning, when the

smoke of fires newly-kindled hangs in azure swathes and veils about the

Old Town—which from that point resembles a huge lizard, the Castle its

head, church-spires spikes upon its scaly back, creeping up from its

lair beneath the Crags to look out on the morning world—one is quite

inclined to pardon the enthusiasm of the North Briton. The finest view

from the interior is obtained from the corner of St Andrew Street,

looking west. Straight before you the Mound crosses the valley, bearing

the white Academy buildings; beyond, the Castle lifts, from grassy

slopes and billows of summer foliage, its weather-stained towers and

fortifications, the Half-Moon battery giving the folds of its standard

to the wind. Living in Edinburgh there abides, above all things, a sense

of its beauty. Hill, crag, castle, rock, blue stretch of sea, the

picturesque ridge of the Old Town, the squares and terraces of the New—

these things seen once are not to be forgotten. The quick life of to-day

sounding around the relics of antiquity, and overshadowed by the august

traditions of a kingdom, makes residence in Edinburgh more impressive

than residence in any other British city. I have just come in—surely

it never looked so fair before? What a poem is that Princes Street! The

puppets of the busy, many-coloured hour move about on its pavement,

while across the ravine Time has piled up the Old Town, ridge on ridge,

gray as a rocky coast washed and worn by the foam of centuries; peaked

and jagged by gable and roof; windowed from basement to cope; the whole

surmounted by St Giles’s airy crown. The New is there looking at the

Old. Two Times are brought face to face, and are yet separated by a

thousand years. Wonderful on winter nights, when the gully is filled

with darkness, and out of it rises, against the sombre blue and the

frosty stars, that mass and bulwark of gloom, pierced and quivering with

innumerable lights. There is nothing in Europe to match that, I think.

Could you but roll a river down the valley it would be sublime. Finer

still, to place one’s-self near the Burns Monument and look toward the

Castle. It is more astonishing than an Eastern dream. A city rises up

before you painted by fire on night. High in air a bridge of lights

leaps the chasm; a few emerald lamps, like glow-worms, are moving

silently about in the railway station below; a solitary crimson one is

at rest. That ridged and chimneyed bulk of blackness, with splendour

bursting out at every pore, is the wonderful Old Town,

where Scottish history mainly transacted itself; while, opposite, the

modern Princes Street is blazing throughout its length. During the day

the Castle looks down upon the city as if out of another world; stern

with all its peacefulness, its garniture of trees, its slopes of grass.

The rock is dingy enough in colour, but after a shower, its lichens

laugh out greenly in the returning sun, while the rainbow is brightening

on the lowering sky beyond. How deep the shadow which the Castle throws

at noon over the gardens at its feet where the children play! How grand

when giant bulk and towery crown blacken against sunset! Fair, too, the

New Town sloping to the sea. From George Street which crowns the ridge,

the eye is led down sweeping streets of stately architecture to the

villas and woods that fill the lower ground, and fringe the shore; to

the bright azure belt of the Forth with its smoking steamer or its

creeping sail; beyond, to the shores of Fife, soft blue, and flecked

with fleeting shadows in the keen clear light of spring, dark purple in

the summer heat, tarnished gold in the autumn haze; and farther away

still, just distinguishable on the paler sky, the crest of some distant

peak, carrying the imagination into the illimitable world. Residence

in Edinburgh is an education in itself. Its beauty refines one like

being in love. It is perennial, like a play of Shakespeare’s. Nothing

can stale its infinite variety.

From

a historical and picturesque point of view, the Old Town is the most

interesting part of Edinburgh; and the great street running from

Holyrood to the Castle—in various portions of its length called the

Lawnmarket, the High Street, and the Canongate—is the most interesting

part of the Old Town. In that street the houses preserve their ancient

appearance; they climb up heavenward, story upon story, with outside

stairs and wooden panellings, all strangely peaked and gabled. With the

exception of the inhabitants, who exist amidst squalor, and filth, and

evil smells undeniably modern, everything in this long street breathes

of the antique world. If you penetrate the narrow wynds that run at

right angles from it, you see traces of ancient gardens. Occasionally

the original names are retained, and they touch the visitor

pathetically, like the scent of long-withered flowers. Old armorial

bearings may yet be traced above the doorways. Two centuries ago fair

eyes looked down from yonder window, now in possession of a drunken

Irishwoman. If we but knew it, every crazy tenement has its tragic

story; every crumbling wall could its tale unfold. The Canongate is

Scottish history fossilised. What ghosts of kings and queens walk there!

What strifes of steel-clad nobles! What wretches borne along, in the

sight of peopled windows, to the grim embrace of the "maiden

!" What hurrying of burgesses to man the city walls at the approach

of the Southron! What lamentations over disastrous battle days! James

rode up this street on his way to Flodden. Montrose was dragged up

hither on a hurdle, and smote, with disdainful glance, his foes gathered

together on the balcony. Jenny Geddes flung her stool at the priest in

the church yonder. John Knox came up here to his house after his

interview with Mary at Holyrood—grim and stern, and unmelted by the

tears of a queen. In later days the Pretender rode down the Canongate,

his eyes dazzled by the glitter of his father’s crown, while bagpipes

skirled around, and Jacobite ladies, with white knots in their bosoms,

looked down from lofty windows, admiring the beauty of the "Young

Ascanius," and his long yellow hair. Down here of an evening rode

Dr Johnson and Boswell, and turned in to the White Horse. David Hume had

his dwelling in this street, and trod its pavements, much meditating the

wars of the Roses and the Parliament, and the fates of English

sovereigns. One day a burly ploughman from black eyes, came down here

and turned into yonder churchyard to stand, with cloudy lids and

forehead reverently bared, beside the grave of poor Ayrshire, with

swarthy features and wonderful Fergusson. Down the street, too, often

limped a little boy, Walter Scott by name, destined in after years to

write its "Chronicles." The Canongate once seen is never to be

forgotten. The visitor starts a ghost at every step. Nobles, grave

senators, jovial lawyers, had once their abodes here. In the old,

low-roofed rooms, half-way to the stars, philosophers talked, wits

coruscated, and gallant young fellows, sowing wild oats in the middle of

last century, wore rapiers and lace ruffles, and drank claret jovially

out of silver stoups. In every room a minuet has been walked, while

chairmen and linkmen clustered on the pavement beneath. But the

Canongate has fallen from its high estate. Quite another race of people

are its present inhabitants. The vices to be seen are not genteel.

Whisky has supplanted claret. Nobility has fled, and squalor taken

possession. Wild, half-naked children swarm around every door-step.

Ruffians lounge about the mouths of the wynds. Female faces, worthy of

the "Inferno," look down from broken windows. Riots are

frequent; and drunken mothers reel past scolding white atomies of

children that nestle wailing in their bosoms—little wretches to whom

Death were the greatest benefactor. The Canongate is avoided by

respectable people, and yet it has many visitors. The tourist is anxious

to make acquaintance with it. Gentlemen of obtuse olfactory nerve, and

of an antiquarian turn of mind, go down its closes and climb its spiral

stairs. Deep down these wynds the artist pitches his stool, and spends

the day sketching some picturesque gable or doorway. The fever-van comes

frequently here to convey some poor sufferer to the hospital. Hither

comes the detective in plain clothes on the scent of a burglar. And when

evening falls, and the lamps are lit, there is a sudden hubbub and crowd

of people, and presently from its midst emerge a couple of policemen and

a barrow with a poor, half-clad, tipsy woman from the sister island

crouching upon it, her hair hanging loose about her face, her hands

quivering with impotent rage, and her tongue wild with curses. Attended

by small boys, who bait her with taunts and nicknames, and who

appreciate the comic element which so strangely underlies the horrible

sight, she is conveyed to the police cell, and will be brought before

the magistrate to-morrow—for the twentieth time perhaps—as a

"drunk and disorderly," and dealt with accordingly. This is

the kind of life the Canongate presents to-day—a contrast with the

time when the tall buildings enclosed the high birth and beauty of a

kingdom, and when the street beneath rang to the horse-hoofs of a king. From

a historical and picturesque point of view, the Old Town is the most

interesting part of Edinburgh; and the great street running from

Holyrood to the Castle—in various portions of its length called the

Lawnmarket, the High Street, and the Canongate—is the most interesting

part of the Old Town. In that street the houses preserve their ancient

appearance; they climb up heavenward, story upon story, with outside

stairs and wooden panellings, all strangely peaked and gabled. With the

exception of the inhabitants, who exist amidst squalor, and filth, and

evil smells undeniably modern, everything in this long street breathes

of the antique world. If you penetrate the narrow wynds that run at

right angles from it, you see traces of ancient gardens. Occasionally

the original names are retained, and they touch the visitor

pathetically, like the scent of long-withered flowers. Old armorial

bearings may yet be traced above the doorways. Two centuries ago fair

eyes looked down from yonder window, now in possession of a drunken

Irishwoman. If we but knew it, every crazy tenement has its tragic

story; every crumbling wall could its tale unfold. The Canongate is

Scottish history fossilised. What ghosts of kings and queens walk there!

What strifes of steel-clad nobles! What wretches borne along, in the

sight of peopled windows, to the grim embrace of the "maiden

!" What hurrying of burgesses to man the city walls at the approach

of the Southron! What lamentations over disastrous battle days! James

rode up this street on his way to Flodden. Montrose was dragged up

hither on a hurdle, and smote, with disdainful glance, his foes gathered

together on the balcony. Jenny Geddes flung her stool at the priest in

the church yonder. John Knox came up here to his house after his

interview with Mary at Holyrood—grim and stern, and unmelted by the

tears of a queen. In later days the Pretender rode down the Canongate,

his eyes dazzled by the glitter of his father’s crown, while bagpipes

skirled around, and Jacobite ladies, with white knots in their bosoms,

looked down from lofty windows, admiring the beauty of the "Young

Ascanius," and his long yellow hair. Down here of an evening rode

Dr Johnson and Boswell, and turned in to the White Horse. David Hume had

his dwelling in this street, and trod its pavements, much meditating the

wars of the Roses and the Parliament, and the fates of English

sovereigns. One day a burly ploughman from black eyes, came down here

and turned into yonder churchyard to stand, with cloudy lids and

forehead reverently bared, beside the grave of poor Ayrshire, with

swarthy features and wonderful Fergusson. Down the street, too, often

limped a little boy, Walter Scott by name, destined in after years to

write its "Chronicles." The Canongate once seen is never to be

forgotten. The visitor starts a ghost at every step. Nobles, grave

senators, jovial lawyers, had once their abodes here. In the old,

low-roofed rooms, half-way to the stars, philosophers talked, wits

coruscated, and gallant young fellows, sowing wild oats in the middle of

last century, wore rapiers and lace ruffles, and drank claret jovially

out of silver stoups. In every room a minuet has been walked, while

chairmen and linkmen clustered on the pavement beneath. But the

Canongate has fallen from its high estate. Quite another race of people

are its present inhabitants. The vices to be seen are not genteel.

Whisky has supplanted claret. Nobility has fled, and squalor taken

possession. Wild, half-naked children swarm around every door-step.

Ruffians lounge about the mouths of the wynds. Female faces, worthy of

the "Inferno," look down from broken windows. Riots are

frequent; and drunken mothers reel past scolding white atomies of

children that nestle wailing in their bosoms—little wretches to whom

Death were the greatest benefactor. The Canongate is avoided by

respectable people, and yet it has many visitors. The tourist is anxious

to make acquaintance with it. Gentlemen of obtuse olfactory nerve, and

of an antiquarian turn of mind, go down its closes and climb its spiral

stairs. Deep down these wynds the artist pitches his stool, and spends

the day sketching some picturesque gable or doorway. The fever-van comes

frequently here to convey some poor sufferer to the hospital. Hither

comes the detective in plain clothes on the scent of a burglar. And when

evening falls, and the lamps are lit, there is a sudden hubbub and crowd

of people, and presently from its midst emerge a couple of policemen and

a barrow with a poor, half-clad, tipsy woman from the sister island

crouching upon it, her hair hanging loose about her face, her hands

quivering with impotent rage, and her tongue wild with curses. Attended

by small boys, who bait her with taunts and nicknames, and who

appreciate the comic element which so strangely underlies the horrible

sight, she is conveyed to the police cell, and will be brought before

the magistrate to-morrow—for the twentieth time perhaps—as a

"drunk and disorderly," and dealt with accordingly. This is

the kind of life the Canongate presents to-day—a contrast with the

time when the tall buildings enclosed the high birth and beauty of a

kingdom, and when the street beneath rang to the horse-hoofs of a king.

The New Town is divided

from the Old by a gorge or valley, now occupied by a railway station;

and the means of communication are the Mound, Waverley Bridge, and the

North Bridge. With the exception of the Canongate, the more filthy and

tumble-down portions of the city are well kept out of sight. You stand

on the South Bridge, and looking down, instead of a stream, you see the

Cowgate, the dirtiest, narrowest, most densely peopled of Edinburgh

streets. Admired once by a French ambassador at the court of one of the

Jameses, and yet with certain traces of departed splendour, the Cowgate

has fallen into the sere and yellow leaf of furniture brokers,

second-hand jewellers, and vendors of deleterious alcohol. These

second-hand jewellers’ shops, the trinkets seen by bleared gaslight,

are the most melancholy sights I know. Watches hang there that once

ticked comfortably in the fobs of prosperous men, rings that were once

placed by happy bridegrooms on the fingers of happy brides, jewels in

which lives the sacredness of death-beds. What tragedies, what

disruptions of households, what fell pressure of poverty brought them

here! Looking in through the foul windows, the trinkets remind one of

shipwrecked gold embedded in the ooze of ocean—gold that speaks of

unknown, yet certain, storm and disaster, of the yielding of planks, of

the cry of drowning men. Who has the heart to buy them, I wonder? The

Cowgate is the Irish portion of the city. Edinburgh leaps over it with

bridges; its inhabitants are morally and geographically the lower

orders. They keep to their own quarters, and seldom come up to the light

of day. Many an Edinburgh man has never set his foot in the street; the

condition of the inhabitants is as little known to respectable Edinburgh

as are the habits of moles, earth-worms, and the mining population. The

people of the Cowgate seldom visit the upper streets. You may walk about

the New Town for a twelvemonth before one of these Cowgate pariahs comes

between the wind and your gentility. Should you wish to see that strange

people "at home," you must visit them. The Cowgate will not

come to you: you must go to the Cowgate. The Cowgate holds high drunken

carnival every Saturday night; and to walk along it then, from the West

Port, through the noble open space of the Grassmarket—where the

Covenanters and Captain Porteous suffered—on to Holyrood, is one of

the world’s sights, and one that does not particularly raise your

estimate of human nature. For nights after your dreams will pass from

brawl to brawl, shoals of hideous faces will oppress you, sodden

countenances of brutal men, women with loud voices and frantic

gesticulations, children who have never known innocence. It is amazing

of what ugliness the human face is capable. The devil marks his children

as a shepherd marks his sheep—that he may know them and claim them

again. Many a face flits past here bearing the sign-manual of the fiend.

But Edinburgh keeps all

these evil things out of sight, and smiles, with Castle, tower,

church-spire, and pyramid rising into sunlight out of garden spaces and

belts of foliage. The Cowgate has no power to mar her beauty. There may

be a canker at the heart of the peach—there is neither pit nor stain

on its dusty velvet. Throned on crags, Edinburgh takes every eye; and,

not content with supremacy in beauty, she claims an intellectual

supremacy also. She is a patrician amongst British cities, "A

penniless lass wi’ a lang pedigree." She has wit if she lacks

wealth: she counts great men against millionaires. The success of the

actor is insecure until thereunto Edinburgh has set her seal. The poet

trembles before the Edinburgh critics. The singer respects the delicacy

of the Edinburgh ear. Coarse London may roar with applause: fastidious

Edinburgh sniffs disdain, and sneers reputations away. London is the

stomach of the empire—Edinburgh the quick, subtle, far-darting brain.

Some pretension of this kind the visitor hears on all sides of him. It

is quite wonderful how Edinburgh purrs over her own literary

achievements. Swift, in the dark years that preceded his death, looking

one day over some of the productions of his prime, exclaimed, "Good

heaven! what a genius I once was!" Edinburgh, looking some fifty

years back on herself, is perpetually expressing astonishment and

delight. Mouldening Highland families, when they are unable to retain a

sufficient following of servants, fill up the gaps with ghosts. Edinburgh

maintains her dignity after a similar fashion, and for a similar reason.

Lord-Advocate Moncreiff, one of the members for the city, hardly ever

addresses his fellow-citizens without recalling the names of Jeffrey,

Cockburn, Rutherfurd, and the other stars that of yore made the welkin

bright. On every side we hear of the brilliant society of forty years

ago. Edinburgh considers herself supreme in talent—just as it is taken

for granted to-day that the present English navy is the most powerful in

the world, because Nelson won Trafalgar. The Whigs consider the Edinburgh

Review the most wonderful effort of human genius. The Tories would

agree with them, if they were not bound to consider Blackwood’s

Magazine a still greater effort. It may be said that Burns, Scott,

and Carlyle are the only men really great in literature—taking great in a European sense—who, during the last eighty years, have been

connected with Edinburgh. I do not include Wilson in the list; for

although he was as splendid as any of these for the moment, he was

evanescent as a Northern light. In the whole man there was something

spectacular. A review is superficially very like a battle. In both there

is the rattle of musketry, the boom of great guns, the deploying of

endless brigades, charges of brazen squadrons that shake the ground—only

the battle changes kingdoms, while the review is gone with its own

smoke-wreaths. Scott lived in or near Edinburgh during the whole course

of his life. Burns lived there but a few months. Carlyle went to London

early, where he has written his important works, and made his

reputation. Let the city boast of Scott—no one will say she does wrong

in that—but it is not so easy to discover the amazing brilliancy of

her other literary lights. Their reputations, after all, are to a great

extent local. What blazes a sun at Edinburgh, would, if transported to

London, not unfrequently become a farthing candle. Lord Jeffrey—when

shall we cease to hear his praises? With perfect truthfulness one may

admit that his lordship was no common man. His "vision" was

sharp and clear enough within its range. He was unable to relish certain

literary forms, as some men are unable to relish certain dishes—an

inaptitude that might arise from fastidiousness of palate, or from

weakness of digestion. His style was perspicuous; he had an icy sparkle

of epigram and antithesis, some wit, and no enthusiasm. He wrote many

clever papers, made many clever speeches, said many clever things. But

the man who could so egregiously blunder as to "Wilhelm

Meister," who hooted Wordsworth through his entire career, who had

the insolence to pen the sentence that opens the notice of the

"Excursion" in the Edinburgh Review, and who, when

writing tardily, but really well, on Keats, could pass over the "Hyperion"

with a slighting remark, might be possessed of distinguished parts, but

no claim can be made for him to the character of a great critic. Hazlitt,

wilful, passionate, splendidly- gifted, in whose very eccentricities and

fierce vagaries there was a generosity which belongs only to fine

natures, has sunk away into an almost unknown London grave, and his

works into unmerited oblivion; while Lord Jeffrey yet makes radiant with

his memory the city of his birth. In point of natural gifts and

endowment — in point, too, of literary issue and result — the

Englishman far surpassed the Scot. Why have their destinies been so

different? One considerable reason is that Hazlitt lived in London—Jeffrey

in Edinburgh. Hazlitt was partially lost in an impatient crowd and rush

of talent. Jeffrey stood, patent to every eye, in an open space in which

there were few competitors. London does not brag about Hazlitt

— Edinburgh brags about Jeffrey. The Londoner, when he visits

Edinburgh, is astonished to find that it possesses a Valhalla filled

with gods — chiefly legal ones — of whose names and deeds he was

previously in ignorance. The ground breaks into unexpected flowerage

beneath his feet. He may conceive to-day to be a little cloudy—may

even suspect east wind to be abroad, but the discomfort is balanced by

the reports he hears on every side of the beauty, warmth, and splendour

of yesterday. He puts out his hands and warms them, if he can, at that

fire of the past. "Ah! that society of forty years ago! Never on this earth did the like exist. Those astonishing men, Homer,

Jeffrey, Cockburn, Rutherfurd! What wit was theirs— what eloquence,

what genius! What a city this Edinburgh once was!"

Edinburgh is not only in

point of beauty the first of British cities—but, considering its

population, the general tone of its society is more intellectual than

that of any other. In no other city will you find so general an

appreciation of books, art, music, and objects of antiquarian interest.

It is peculiarly free from the taint of the ledger and the

counting-house. It is a Weimar without a Goethe—Boston without its

nasal twang. But it wants variety; it is mainly a city of the

professions. London, for instance, contains every class of people; it is

the seat of legislature as well as of wealth; it embraces Seven Dials as

well as Beigravia. In that vast community class melts imperceptibly into

class, from the Sovereign on the throne to the wretch in the condemned

cell. In that finely-graduated scale, the professions take their own

place. In Edinburgh matters are quite different. It retains the gauds

which royalty cast off when it went South, and takes a melancholy

pleasure in regarding these—as a lady the love-tokens of a lover who

has deserted her to marry into a family of higher rank. A crown and

sceptre lie up in the Castle, but no brow wears the diadem, no hand

lifts the golden rod. There is a palace at the foot of the Canongate,

but it is a hotel for her Majesty, en route for Balmoral—a

place where the Commissioner to the Church of Scotland holds his phantom

Court. With these exceptions, the old halls echo only the footfalls of

the tourist and sight-seer. When royalty went to London, nobility

followed; and in Edinburgh the field is left now, and has been so left

for a long time back, to Law, Physic, and Divinity. The professions

predominate: than these there is nothing higher. At Edinburgh a Lord of

Session is a Prince of the Blood, a Professor a Cabinet Minister, an

Advocate an heir to a peerage. The University and the Courts of Justice

are to Edinburgh what the Court and the Houses of Lords and Commons are

to London. That the Scottish nobility should spend their seasons in

London is not to be regretted for the sake of Edinburgh shopkeepers only—their

absence affects interests infinitely higher. In the event of a

superabundance of princes, and a difficulty as to what should be done

with them, it has been frequently suggested that one should be stationed

in Dublin, another in Edinburgh, to hold Court in these cities Gold is

everywhere preferred to paper; and in the Irish capital royalty in the

person of Prince Patrick would be more satisfactory than its shadow in

the person of a Lord-Lieutenant. A Prince of the Blood in Dublin would

be gratefully received by the warm-hearted Irish people. His permanent

presence amongst them would cancel the remembrance of centuries of

misgovernment; it would strike away for ever the badge and collar of

conquest. In Edinburgh we have had princes of late years, and seen the

uses of them. A prince at Holyrood would effect for the country what

Scottish Rights’ Associations and University reformers have so long

desired. The nobility would again gather—for a portion of the year at

least—to their ancient capital; and their sons, as of old, would be

found in the University class-rooms. Under the new influence, life would

be gayer, airier, brighter. The social tyranny of the professions would

to some extent be broken up, the atmosphere would become less legal, and

a new standard would be introduced whereby to measure men and their

pretensions. For the Prince himself, good results might be expected. He

would at the least have some specific public duties to perform; and he

would, through intercourse, become attached to the people, as the people

in their turn would become attached to him. Edinburgh needs some little

gaiety and courtly pomp to break the coldness of gray stony streets; to

brighten a somewhat sombre atmosphere; to mollify the east wind that

blows half the year, and the "professional sectarianism" that

blows the whole year round. You always suspect the east wind, somehow,

in the city. You go to dinner: the east wind is blowing chillily from

hostess to host. You go to church, a bitter east wind is blowing in the

sermon. The text is that divine one, GOD IS LOVE; and the discourse that

follows is full of all uncharitableness.

Of all British cities,

Edinburgh—Weimar-like in its intellectual and aesthetic leanings,

Florence-like in its freedom from the stains of trade, and more than

Florence-like in its beauty—is the one best suited for the conduct of

a lettered life. The city as an entity does not stimulate like London,

the present moment is not nearly so intense, life does not roar and

chafe—it murmurs only; and this interest of the hour, mingled with

something of the quietude of distance and the past—which is the

spiritual atmosphere of the city—is the most favourable of all

conditions for intellectual work or intellectual enjoyment. You have

libraries—you have the society of cultivated men and women—you have

the eye constantly fed by beauty—the Old Town, jagged, picturesque,

piled up; and the airy, open, coldly-sunny, unhurried, uncrowded streets

of the New Town—and, above all, you can "sport your oak," as

they say at Cambridge, and be quit of the world, the gossip, and the

dun. In Edinburgh, you do not require to create quiet for yourself; you

can have it ready-made. Life is leisurely; but it is not the leisure of

a village, arising from a deficiency of ideas and motives — it is the

leisure of a city reposing grandly on tradition and history, which has

done its work, which does not require to weave its own clothing, to dig

its own coals, to smelt its own iron. And then, in Edinburgh, above all

British cities, you are released from the vulgarising dominion of the

hour. The past confronts you at every street corner. The Castle looks

down out of history on its gayest thoroughfare. The winds of fable are

blowing across Arthur’s Seat. Old kings dwelt in Holyrood. Go out of

the city where you will, the past attends you like a cicerone. Go down

to North Berwick, and the red shell of Tantallon speaks to you of the

might of the Douglases. Across the sea, from the gray-green Bass,

through a cloud of gannets, comes the sigh of prisoners. From the long

sea-board of Fife—which you can see from George Street—starts a

remembrance of the Jameses. Queen Mary is at Craigmillar, Napier at

Merchiston, Ben Jonson and Drummond at Hawthornden, Prince Charles in

the little inn at Duddingston; and if you go out to Linlithgow, there is

the smoke of Bothwellhaugh’s fusee, and the Great Regent falling in

the crooked street. Thus the past checkmates the present. To an

imaginative man, life in or near Edinburgh is like residence in an old

castle:—the rooms are furnished in consonance with modern taste and

convenience; the people who move about wear modern costume, and talk of

current events in current colloquial phrases; there is the last

newspaper and book in the library, the air from the last new opera in

the drawing-room; but while the hour flies past, a subtle influence

enters into it—enriching, dignifying—from oak panelling and carvings

on the roof—from the picture of the peaked-bearded ancestor on the

wall—from the picture of the fanned and hooped lady—from the old

suit of armour and the moth-eaten banner. On the intellectual man,

living or working in Edinburgh, the light comes through the stained

window of the past. To-day’s event is not raw and brusque; it

comes draped in romantic Colour, hued with ancient gules and or. And

when he has done his six hours’ work, he can take the noblest and most

renovating exercise. He can throw down his pen, put aside his papers,

and walk round the Queen’s Drive, where the wind from the sea is

always fresh and keen; and in his hour’s walk he has wonderful variety

of scenery—the fat Lothians—the craggy hillside—the valley, which

seems a bit of the Highlands—the wide sea, with smoky towns on its

margin, and islands on its bosom—lakes with swans and rushes—ruins

of castle, palace, and chapel—and, finally, homeward by the high

towering street through which Scottish history has rushed like a stream.

There is no such hour’s walk as this for starting ideas, or, having

started, captured, and used them, for getting quit of them again.

Edinburgh is at this

moment in the full blaze of her beauty. The public gardens are in

blossom. The trees that clothe the base of the Castle rock are clad in

green: the "ridgy back" of the Old Town jags the clear azure.

Princes Street is warm and sunny—’tis a very flower-bed of parasols,

twinkling, rainbow-coloured. Shop windows are enchantment, the flag

streams from the Halfmoon Battery, church-spires sparkle sun-gilt, gay

equipages dash past, the military band is heard from afar. The tourist

is already here in wonderful Tweed costume. Every week the wanderers

increase, and in a short time the city will be theirs. By August the

inhabitants have fled. The University lets loose, on unoffending

humanity, a horde of juvenile M.D.’s warranted to dispense— with the

sixth commandment. Beauty listens to what the wild waves are saying.

Valour cruises in the Mediterranean; and Law, up to the knees in

heather, stalks his stag on the slopes of Ben-Muichdhui. Those who, from

private and most urgent reasons, are forced to remain behind, put brown

paper in their front windows; inform the world by placard that letters

and parcels may be left at No. 26 round the corner, and live

fashionably in their back-parlours. At twilight only do they adventure

forth; and if they meet a friend—who ought like the rest of the world

to be miles away—they have only of course come up from the sea-side,

or their relation’s shooting-box, for a night, to look after some

imperative business. Tweed - clad tourists are everywhere: they stand on

Arthur’s Seat, they speculate on the birthplace of Mons Meg, they

admire Roslin, eat haggis, attempt whisky-punch, and crowd to Dr Guthrie’s

church on Sundays. By October the last tourist has departed, and the

first student has arrived. Tailors put forth their gaudiest fabrics to

attract the eye of ingenuous youth. Whole streets bristle with

"lodgings to let" Edinburgh is again filled. The University

class-rooms are crowded; a hundred schools are busy; and Young Briefless,

"Who never is, but

always to be, fee’d,"

the sun-brown yet on his

face, paces the floor of the Parliament House, four hours a day, in his

professional finery of horse-hair and bombazine. During the winter-time

are assemblies and dinner-parties. There is a fortnight’s opera, with

the entire fashionable world in the boxes. The Philosophical Institution

is in full session; while a whole army of eloquent lecturers do battle

with ignorance on public platforms—each effulging like Phoebus, with

his waggon-load of blazing day—at whose coming night perishes, shot

through with orient beams. Neither mind nor body is neglected during the

Edinburgh season.

In spring time, when the

east winds blow, and grey walls of haar—clammy, stinging, heaven-high,

making disastrous twilight of the brightest noon—come in from the

German Ocean, and when coughs and colds do most abound, the Royal

Scottish Academy opens her many-pictured walls. From February to May

this is the most fashionable lounge in Edinburgh. The rooms are warm, so

thickly carpeted that no footfall is heard, and there are seats in

abundance. It is quite wonderful how many young ladies and gentlemen get

suddenly interested in art. The Exhibition is a charming place for

flirtation; and when Romeo is short in the matter of small talk—as

Romeo sometimes will be—there is always a picture at hand to suggest a

topic. Romeo may say a world of pretty things while he turns up the

number of a picture in Juliet’s catalogue—for without a catalogue

Juliet never appears in the rooms. Before the season closes, she has her

catalogue by heart, and could repeat it to you from beginning to end

more glibly than she could her Catechism. Cupid never dies; and fingers

will tingle as sweetly when they touch over an Exhibition catalogue as

over the dangerous pages of "Lancelot of the Lake." If many

marriages are not made here, there are gay deceivers in the world, and

the picture of deserted Ophelia—the blank smile on her mouth,

flowerets stuck in her yellow hair—slowly sinking in the weedy pool,

produces no suitable moral effect. To other than young ladies and

gentlemen the rooms are interesting, for Scottish art is at this moment

more powerful than Scottish literature. Perhaps some half-dozen pictures

in each Academy’s Exhibition are the most notable intellectual

products that Scotland can present for the year. The Scottish brush is

stronger than the Scottish pen. It is in landscape and—at all events

up till the other day, when Sir John Watson Gordon died—in portraiture

that the Scotch school excels. It excels in the one in virtue of the

national scenery, and in the other in virtue of the national insight and

humour. For the making of a good portrait a great deal more is required

than excellent colour and dexterous brush-work—shrewdness, insight,

imagination, common sense, and many another mental quality besides, are

needed. No man can paint a good portrait unless he knows his sitter

thoroughly; and every good portrait is a kind of biography. It is

curious, as indicating that the instinct for biography and

portrait-painting are alike in essence, that in both walks of art the

Scotch have been unusually successful. It would seem that there is

something in the national character predisposing to excellence in these

departments of effort. Strictly to inquire how far this predisposition

arises from the national shrewdness or the national humour, would be

needless; thus much is certain, that Scotland has at various times

produced the best portrait-painters and the best writers of biography to

be found in the compass of the islands. In the past, she can point to

Boswell’s "Life of Johnson" and Raeburn’s portraits: she

yet can claim Thomas Carlyle; and but lately she could claim Sir John

Watson Gordon. Thomas Carlyle is a portrait-painter, and Sir John Watson

Gordon was a biographer.

On the walls of the

Exhibition, as I have said, will be found some of the best products of

the Scottish brain. There, year after year, are to be found the pictures

of Mr Noel Paton—some, of the truest pathos, like the "Home from

the Crimea;" or that group of ladies and children in the cellar at

Cawnpore, listening to the footsteps of deliverers, whom they conceive

to be destroyers; or "Luther at Erfurt," the gray morning

light breaking in on him as he is with fear and trembling working out

his own salvation—and the world’s. We have these, but we have at

times others quite different from these, and of a much lower scale of

excellence, although hugely admired by the young people aforesaid —

pictures in which attire is painted instead of passion; where the merit

consists in exquisite renderings of unimportant details— jewels,

tassels, and dagger hilts; where a landscape is sacrificed to a bunch of

ferns, a tragic situation to the pattern on the lady’s zone, or the

slashed jacket and purple leggings of the knight. Then there are Mr

Drummond’s pictures from Scottish history and ballad poetry—a string

of wild moss-troopers riding over into England to lift cattle; John Knox

on his wedding-day leading his wife home to his quaint dwelling in the

Canon-gate; the wild lurid Grassmarket, crowded with rioters, crimson

with torchlight, spectators filling every window of the tall houses,

while Porteous is being carried to his death—the Castle standing high

above the tumult against the blue midnight and the stars; or the death

procession of Montrose— the hero seated on hurdle, not on

battle-steed, with beard untrimmed, hair dishevelled, dragged through

the crowded street by the city hangman and his horses, yet proud of

aspect, as if the slogans of Inverlochy were ringing in his ears, and

flashing on his enemies on the balcony above him the fires of his

disdain. Then there are Mr Harvey’s solemn twilight moors, and

covenanting scenes of marriage, baptism, and funeral. And drawing the

eye with a stronger fascination—because they represent the places in

which we are about to wander—the landscapes of Horatio Macculloch—stretches

of Border moorland, with solitary gray peels on which the watery sunbeam

strikes, a thread of smoke rising far off from the gipsy’s fire; Loch

Scavaig in its wrath, the thunder gloom blackening on the peaks of

Cuchullin, the fierce rain crashing down on white rock and shingly

shore; sunset on Loch Ard, the mountains hanging inverted in the golden

the winding Awe. He is the most national of the northern

landscape-painters; and although he can, on occasion, paint grasses and

flowers, and the shimmer of reed-blades in the wind, he loves mirror, a

plump of water-fowl starting from the reeds in the foreground, and

shaking the splendour into dripping wrinkles and widening rings; Ben

Cruachan wearing his streak of snow at midsummer, and looking down on

Kilchurn Castle and vast desolate spaces, the silence of the Highland

wilderness where the wild deer roam, the shore on which subsides the

last curl of the indolent wave. He loves the tall crag wet and gleaming

in the sunlight, the rain-cloud on the moor, blotting out the distance,

the setting sun raying out lances of flame from behind the stormy

clouds—clouds torn, but torn into gold, and flushed with a brassy

radiance.

May is an exciting month

in Edinburgh, for, towards its close, the Assemblies of the Established

and Free Churches meet. For a fortnight or so the clerical element

predominates in the city. Every presbytery in Scotland sends up its

representative to the metropolis, and an astonishing number of black

coats and white neckcloths flit about the streets. At high noon the

gaiety of Princes Street is subdued with innumerable suits of sable.

Ecclesiastical newspapers let the world wag as it pleases, so intent are

they on the debates. Rocky-featured elders from the far north come up

interested in some kirk dispute; and junior counsel waste the midnight

oil preparing for appearance at the bar of the House. The opening of the

General Assembly of the Church of Scotland is attended with a pomp and

circumstance which seems a little at variance with Presbyterian quietude

of tone and contempt of sacerdotal vanities. Her Majesty’s Lord High

Commissioner resides at Holyrood, and on the morning of the day on which

the Assembly opens he holds his first levee. People rush to warm

themselves in the dim reflection of the royal sunshine, and return with

faces happy and elate. On the morning the Assembly opens, the military

line the streets from Holyrood to the Assembly Hall. A regimental band

and a troop of lancers wait outside the palace gates while the

procession is slowly getting itself into order. The important moment at

length arrives. The Commissioner has taken his seat in the carriage. Out

bursts the brass band, piercing every ear; the lancers caracole; an

orderly rides with eager spur; the long train of carriages begins to

crawl forward in an intermittent manner, with many a dreary pause. At

last the head of the procession appears along the peopled way. First

come, in hired carriages, the city councillors, clothed in scarlet

robes, and with cocked hats upon their heads. The very mothers that bore

them could not recognise them now. They pass on silent with dignity.

Then comes a troop of halberdiers in mediaeval costume, and looking for

all the world as if the Kings, Jacks, and Knaves had walked out of a

pack of cards. Then comes a carriage full of magistrates, wearing their

gold chains of office over their scarlet cloaks, and eyeing sternly the

small boy in the crowd who, from a natural sense of humour, has given

vent to an irreverent observation. Then comes the band; then a squadron

of lancers, whose horses the music seems to affect; then a carriage

occupied with high legal personages, with powder in their hair, and

rapiers by their sides, which they could not draw for their lives. Then

comes the private carriage of his Grace, surrounded by lancers, whose

mercurial steeds plunge and rear, and back and sidle, and scatter the

mob as they come prancing broadside on to the pavement, smiting sparks

of fire from the kerbstones with their iron hoofs. Thereafter, Tom,

Jack, and Harry, for every cab, carriage, and omnibus of the line of

route is now allowed to fall in—and so, attended by halberdiers, and

soldiers, and a brass band, her Majesty’s Commissioner goes to open

the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland. As his Grace has to

attend all the sittings of the reverend court, the Government, it is

said, generally selects for the office a nobleman slightly dull of

hearing. The Commissioner has no power, he has no voice in the

deliberations; but he is indispensable, as a corporation mace is

indispensable at a corporation meeting. While the debate is going on

below, and two reverend fathers are passionately throttling each other,

he is not unfrequently seen, with spectacles on nose, placidly perusing

the Times. He is allowed two thousand pounds a year, and his duty

is to spend it. He keeps open table for the assembled clergymen. He

holds a grand evening levee, to which several hundred people are

invited. If you are lucky enough to receive a card of invitation, you

fall into the line of carriages opposite the Register House about eight

o’clock, you are off the High School at nine, ten peals from the

church-spires when you are at the end of Regent Terrace, and by eleven

your name is being shouted by gorgeous lackeys —whose income is

probably as great as your own— through the corridors of Holyrood as

you advance towards the presence. When you arrive you find that the

country parson, with his wife and daughter, have been before you, and

you are a lucky man if, for refreshment, you can secure a bit of

remainder sponge-cake and a glass of lukewarm sherry. On the last

occasion of the Commissioner’s levee the newspapers inform me that

seventeen hundred invitations were issued. Think of it—seventeen

hundred persons on that evening bowed before the Shadow of Majesty, and

then backed in their gracefulest manner. On that evening the Shadow of

Majesty performed seventeen hundred genuflections! I do not grudge the

Lord Commissioner his two thousand pounds. Verily, the labourer is

worthy of his hire. The vale of life is not without its advantages. |