|

Part III

Military Annals of

the Highland Regiments

Section V

Montgomery's Highlanders.

Expedition under Colonel

Montgomery against the Cherokees, 1760 —Dominique, 1761—Martinique,

1762—Submission of all the Windward Islands, 1762—Havannah, 1762.

While Lord John Murray's

and Fraser's Highlanders were engaged in these important operations,

Montgomery's Highlanders passed the winter of 1758 and 1759 in Fort du

Quesne, after it had been occupied by Brigadier-General Forbes. In the

month of May 1759, they joined and formed part of the army under General

Amherst in his proceedings at Ticonderoga, Crown Point, and the Lakes. The

cruelty with which the Cherokees prosecuted their renewed hostilities in

the spring of 1760, alarmed all the southern English colonies, and

application was, in consequence, made to the commander-in-chief for

assistance. He therefore detached the Honourable Colonel Montgomery, an

officer of distinguished zeal and activity, with 400 men of the Royals,

700 Highlanders of his own regiment, and a strong detachment of

Provincials, with orders to proceed as expeditiously as possible to the

country of the Cherokees, and after chastising them, to march to New York,

and embark for the expedition against Montreal. In the middle of June, he

reached the neighbourhood of the Indian town Little Keowee, and resolving

to rush upon the enemy by surprise, he left his baggage with a proper

guard, and marched to Estatoe, detaching on his route the light companies

of the Royals and Highlanders to destroy Little Keowee. This they

performed with the loss of a few men killed, and Lieutenants Marshal and

Hamilton of the Royals wounded; but on their arrival at Estatoe, they

found the enemy had fled. Colonel Montgomery then retired to Fort Prince

George; but finding that the recent chastisement had had no effect, he

paid a second visit to the middle settlement. On this occasion however, he

met with more resistance, for he had 2 officers and 20 men killed, and 26

officers and 68 men wounded. Of these the Highlanders had 1 Serjeant and 6

privates killed ; and Captain Sutherland, Lieutenants Macmaster and

Mackinnon, and Assistant-Surgeon Monro, and 1 serjeant, 1 piper, and 24

rank and file, wounded. Having completed this service, he again returned

to Fort Prince George. Meanwhile, the Indians were not idle. They laid

siege to, or rather blockaded, Fort Loudon, a small fort on the confines

of Virginia, defended by 200 men under the command of Captain Denure, and

possessing only a small stock of provisions and ammunition. The garrison,

too weak to encounter the enemy in the field, was at length compelled by •

famine to surrender, on condition of being permitted to march to the

English settlements; but the Indians observing the convention no longer

than their interest required, attacked the garrison on their march, and

killed all the officers except Captain John Stuart. [This officer, who was

of the family of Stewart of Kinchardine in Strathspey, and father of the

late General Sir John Stuart, Count of Maida, acted the same part towards

the Indians as Sir William Johnson, and, so far as his more confined power

and influence extended, with equal success.]

These transactions detained

Colonel Montgomery and his regiment in Virginia, and prevented their

joining the expedition to Montreal, as was intended.

Every object for which war

had been undertaken in America being now accomplished, the attention of

Government was called to the West-Indies, where the possession of

Martinique gave the enemy great opportunities of annoying our commerce in

those seas. The feeble attempt made by General Hopson and Commodore Moore,

in 1759, showing the French their danger more clearly, had induced them to

make every exertion to strengthen their fortified posts, and to maintain a

larger garrison in the island than formerly; so that what might at first

have been accomplished with comparatively little loss, was now likely to

be a work of time, bloodshed, and labour.

Orders were sent to North

America to prepare a large body of troops for the West Indies. Among

these, the four Highland battalions were particularly specified; "as their

sobriety and abstemious habits, great activity, and capability of bearing

the vicissitudes of heat and cold, rendered them well qualified for that

climate, and for a broken and difficult country. [General Instructions,

dated Whitehall, 1759.]

Owing to the differences in

the cabinet at home, and the change of ministers, these orders were not

followed up, and only a few troops reached the West-Indies from North

America. Our commanders being thus unable to attempt Martinique, Colonel

Lord Rollo, and Commodore Sir James Douglas, with a small land force and

four ships of war, undertook an expedition against Dominique.

This force consisted of

part of the garrison of Guadaloupe, the Grenadiers and Light infantry of

the 4th and 22d regiments, under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel

Melville, and 6 companies of Montgomery's Highlanders and others, who had

been sent from New-York. [The transports from New-York, conveying nearly

2000 men, were scattered in a gale of wind. A company of Montgomery's, in

a small transport, were attacked by a French privateer, which they beat

off, with the loss of Lieutenant M'Lean and 6 men killed, and Captain

Robertson and 11 men wounded.] Arriving off Dominique on the 6th of June

1761, they immediately landed, and marched, with little opposition, to the

town of Roseau. From some entrenchments above the town, the enemy kept up

a galling fire. These Lord Rollo resolved to attack without delay,

particularly as he had learned that a reinforcement from Martinique was

shortly expected. This service was performed by his Lordship and Colonel

Melville, at the head of the Grenadiers, Light infantry, and Highlanders,

with such vigour and success, that the enemy were driven, in succession,

from all their works. So rapid was the charge of the Grenadiers and

Highlanders, that few of the British suffered. The Governor and his staff

being taken prisoners, surrendered the colony without more op. position.

This was the only service performed in the American seas during the year

1761.

In the following year, it

was resolved to resume active operations, and to attempt Martinique and

the Havannah, two of the most important stations in the possession of the

French and Spaniards. The plan of operations of the preceding year was

now, therefore, resumed, and eleven regiments having embarked in North

America, arrived at Bar-badoes in December. There they were joined by four

regiments who had been at the attack of Belleisle; and, being reinforced

by some corps from the islands, the whole force amounted to eighteen

regiments, under the command of Major-General Monckton, and Brigadiers

Haviland, James Grant of Ballindalloch, Rufane, and Walsh, and Colonel

Lord Rollo. The naval armament consisted of 18 sail of the line, with

frigates, bomb-vessels, and fireships, under Rear-Admiral Rodney. In this

force were included three battalions of Highlanders, viz. Montgomery's

regiment, and the 1st and 2d battalions of Lord John Murray's. Eraser's

remained in North America.

This powerful armament

sailed from Barbadoes on the 5th of January 1762, and on the 8th, the

fleet anchored in St Ann's Bay, Martinique. An immediate landing was

effected without loss. Brigadiers Grant and Haviland were detached to the

Bay of Ance Darlet, where they made a descent without opposition. On the

16th, General Monckton and the whole army landed in the neighbourhood of

Cas de Navire, under Morne Tortueson and Morne Gamier, two considerable

eminences which overlook and completely command the town and citadel of

Fort Royal. Till these were carried, the town could not be attacked with

any reasonable prospect of success; but if the enterprise should prove

successful, the enemy, without being able to return it, would be exposed

to the fire of these commanding heights, from whence every shot would

plunge through the roof to the foundation of every house in the town.

Suitable precautions had therefore been taken to secure these important

stations against attack. Like the other high grounds in this island, they

were protected by very deep and rocky ravines, and their natural strength

was much improved by art. Morne Tortueson was first attacked. To support

this operation, a body of troops and marines, (800 of the latter having

been landed from the fleet), were ordered to advance on the right, along

the seaside, towards the town, for the purpose of attacking two redoubts

near the beach. Flat-bottomed boats, each carrying a gun, and manned with

sailors, were ordered close in shore to support this movement. On the left

a corps of Light infantry was to get round the enemy's left, whilst the

attack on the centre was made by the Grenadiers and Highlanders, supported

by the main body of the army ; all to be under cover of the fire of the

new batteries, which had been hastily erected on the opposite ridges. With

their usual spirit and activity, the sailors had dragged the cannon to the

summit of these almost perpendicular ridges on which the batteries had

been erected. The necessary arrangements were executed with great

gallantry and perseverance. The attack succeeded in every quarter. The

works were carried in succession; the enemy driven from post to post; and,

after a severe struggle, our troops became masters of the whole Morne.

Thus far they had proceeded with success; but nothing decisive could be

done without possession of the other eminence of Garnier, which, from its

greater height, enabled the enemy to cause much annoyance to our troops.

Three days passed ere proper dispositions could be made for driving them

from this ground. The preparations for this purpose were still unfinished,

when the enemy's whole force descended from the hill, and attacked the

British in their advanced posts. They were immediately repulsed; and the

troops, carried forward by their ardour, converted defence into assault,

and passed the ravines with the fugitives. "The Highlanders, drawing their

swords, rushed forward like furies ; and, being supported by the

Grenadiers under Colonel Grant (Ballendalloch), and a party of Lord

Rollo's brigade, the hills were mounted and the batteries seized, and

numbers of the enemy, unable to escape from the rapi-dity of the attack,

were taken." [Westminster Journal.] The French regulars escaped into the

town, and the militia fled, and dispersed themselves over the country.

This action proved decisive; for the town, being commanded by the heights,

surrendered on the 5th of February. This point being gained, the General

was preparing to move against St Pierre, the capital of the colony, when

his farther proceedings were rendered unnecessary by the arrival of

deputies, who came to arrange terms of submission for that town and the

rest of the island, together with the islands of Grenada, St Vincent, and

St Lucia. This capitulation put the British in possession of all the

Windward Islands.

The loss in this campaign

amounted to 8 officers, 3 sergeants, and 87 rank and file, killed; and 33

officers, 19 sergeants, 4? drummers, and 350 rank and file, wounded. Of

this loss the proportion which fell upon the Royal Highlanders, consisted

of Captain William Cockburn, Lieutenant David Barclay, 1 sergeant and 12

rank and file, killed; Major John Reid, Captains James Murray, [See an

account of his wound in the article Athole Highlanders. This was one of

the many remarkable instances of the rapid cure of the most desperate

gun-shot wounds in the climate of those islands, which proves so

deleterious to European constitutions in fever and inflammatory

complaints.] and Thomas Stirling, Lieutenants Alexander Mackintosh, David

Milne, Patrick Balneaves, Alexander Turnbull, John Robertson, William

Brown, and George Leslie, 3 sergeants, 1 drummer, and 72 rank and file,

wounded. Of Montgomery's Highlanders, Lieutenant Hugh Gordon and 4 rank

and file were killed; and Captain Alexander Mackenzie, 1 sergeant, and 2G

rank and file, wounded.

Great Britain having

declared war against Spain, preparations were made to assail her in the

tenderest point. For this purpose, it was determined to attack, in spring,

the Ha-vannah, the capital of the large island of Cuba, a place of the

greatest importance to Spain, being the key of her vast empire in South

America, and deemed by the Spanish ministry impregnable.

The capture of this strong

town, in which the whole trade and navigation of the Spanish West Indies

centered, would almost finish the war in that quarter; and, if followed up

by farther advantages, would expose to danger the whole of Spanish

America. The command of this important enterprise was intrusted to

Lieutenant-General the Earl of Albemarle, Admiral Sir George Pocock, and

Commodore Keppell, together with Lieutenant-General Elliot, afterwards

Lord Heathfield, Major-Generals Keppell and La Fausille, and

Brigadier-Generals Haviland, Grant, Lord Rollo, Walsh, and Reid. Lord

Rollo, being attacked by fever, was carried on board ship, and proceeded

to England. The following year he died at Leicester, on his way to

Scotland, and was buried with military honours, respected and lamented as

a brave and able officer. Colonel Guy Carleton, succeeded to the command

of his brigade upon his departure.

Much valuable time was lost

in preparations at home: and, instead of reaching the West Indies in time

to sail for their destination immediately after the reduction of

Martinique, the commanders did not leave England with the fleet till the

month of March. The best period for action in these latitudes was thus

lost, and an arduous service was to be undertaken in the most unhealthy

season of the year. One part of the arrangements, however, was well

executed. The fleet arrived off Cape Nicholas on the 27th of May; and

Commodore Sir James Douglas, with a fleet and troops from Martinique,

joined them on the evening of the same day. The armament now included

nineteen sail of the line, besides eighteen frigates and smaller vessels

of war, with the Royals, 4th or King's Own, 9th, 15th, 17th, 22d, 27th or

Inniskilling, 28th, 34th, 35th, 40th, Royal Highlanders, 48th, 56th, 60th,

65th, 72d, 77th or Montgomery's Highlanders, 90th, 98th, two corps of

Provincials, and a detachment of Marines under Lieutenant-Colonel Campbell

of Glenlyon; in all, upwards of 11,000 firelocks. A further reinforcement

of 4000 men was expected from New York. As the hurricane months were

approaching, much of the success of the enterprise depended on expedition.

The Admiral resolved, therefore, to run through the Straights of Old

Bahama, a long narrow and dangerous passage. This bold attempt was

executed with so much judgment and prudence, that the whole fleet,

favoured by good weather,, and sailing in seven divisions, completed,

without loss or interruption, a navigation which is reckoned perilous for

a single ship, and on the 5th of June arrived in sight of the Havannah.

The harbour of this city is

the best in the West Indies. Its entrance is narrow, and is secured on one

side by a fort called the Puntal, surrounded by a strong rampart, flanked

with bastions, and covered by a ditch. In the harbour lay nearly twenty

sail of the line, which, instead of making any attempt to oppose the

operations of the invaders, secured themselves by sinking three ships in

the mouth of the harbour, and throwing an iron-boom across it. The

preparations being completed on the 7th June, the Admiral made a

demonstration to land to the westward, while a body of troops disembarked

to the eastward of the harbour without opposition, the squadron under

Commodore Keppell having previously silenced a small battery on the beach.

The army was divided into two corps, one of which, under

Lieutenant-General Elliot, (afterwards Governor of Gibraltar), was to

cover the siege, and protect the parties employed in procuring water and

provisions,—a service of great importance, for the water was scarce and of

a bad quality, and the salt provisions were in such a state that they were

more injurious than the climate to the health of the army.

[In this respect, as well

as in the size and quality of the ships employed in transporting troops,

there is now a great and important improvement, affording much additional

security to the health of the troops, greater safety on the voyage, and

more chance of success in all enterprises. The provisions of all kinds

(with the exception of rum) are now of the best quality; and from the

existing regulations, which direct all provisions to be surveyed by

boards, composed of officers, it depends on themselves if they allow any

bad provisions to be received. In former times, instances have been known,

where, in consequence of bad and heavy sailing transports, and provisions

improperly cured, voyages have been so tedious, and the troops have become

so sickly, that, on reaching the destined point of attack, nothing could

be attempted. Of this the expedition to Portobello in 1740, celebrated in

so many doleful ballads, is a memorable instance.

Great improvements are

still required. While new rum is so notoriously known to be ruinous to

health, that even the Negroes call it kill the devil, it is matter of

regret that the troops should continue to be poisoned by the issue of such

deleterious liquor. If good rum is dear, let the supply be discontinued;

but when the health of the soldier is at stake, and (considerations of

humanity apart) when the value of a soldier's life on foreign stations,

and the expense of supplying vacancies, are considered, surely the

difference in the value between good and bad spirits, in the daily

allowance to the troops, ought not to be regarded. On the other hand,

when, by proper encouragement, a full supply of the best fresh beef for

all our West India garrisons can be obtained from Trinidad and the Spanish

Main, a third cheaper than salt pork and beef can be sent from England, it

is to be hoped that so important a subject will not be much longer

neglected, and that our troops in tropical climates will not be fed on

salt beef and pork, new rum and dry bread, which, in the language of the

soldiers, who speak what they feel, must in a hot climate be "the devil's

own diet."]

The other division was

commanded by General Keppell, and was intended for the reduction of the

Moro, which commanded the town and the harbour. A detachment, under

Colonel William Howe, was encamped to the westward, to cut off the

communication between the town and the country. In this disposition the

troops remained, occasionally relieving each other in the hardest duties,

during the whole of the siege. The soil was every where so thin and hard,

that the greatest difficulty the besiegers encountered was to cover

themselves in their approaches, and to raise the necessary batteries. But,

in spite of all obstacles, batteries were raised against the Moro, and

some others pushed forward to drive the enemy's ships still farther into

the harbour, and prevent them from molest-ing our troops in their

approaches. The Spaniards did not continue entirely on the defensive. On

the 29th of June, they made a sally with considerable spirit and

resolution, but were forced to retire, leaving nearly 300 men behind them.

In the mean time, the three

largest of the British ships stationed themselves alongside the fort, and

commenced a furious and unequal contest, which continued for nearly seven

hours. But the Moro, from its superior height, and aided by the fire from

the opposite fort of the Puntal, had greatly the advantage of the ships,

which, after displaying the greatest intrepidity, were obliged to

withdraw, after losing Captain Goostrey of the Marlborough, and 150 men

killed and wounded.

Sickness had now spread

among the besiegers, and, to complete their difficulties, the principal

battery opposed to the Moro caught fire on the 3d of July; and blazed with

such fury, that the whole was in twenty minutes consumed. Thus the labour

of 600 men for sixteen days was destroyed in a few minutes, and all was to

be begun anew. This disaster was the more severely felt, as the increasing

sickness made the duty more arduous, and the approaching hurricane season

threatened additional hardships. But the spirit of the troops supported

them against every disadvantage; and, while they had so much cause to

complain of their rancid and damaged provisions, and of the want of fresh

water, though in the very neighbourhood of a river from which the small

transports might have supplied them in abundance, had any attempt been

made to provide a supply; yet the shame of defeat, the prospect of the

rich prize before them, and the honour that would result from taking a

place so strong in itself and so bravely defended, were motives which

excited them to unwearied exertions.

A part of the reinforcement

from North America having arrived, new batteries were quickly raised, and

the Jamaica fleet touching at Havannah, on the passage home, left such

supplies as they could spare of necessaries for the siege. Fresh vigour

was thus infused.

After various operations on

both sides, the enemy, on the 22d of July, made a sortie, with 1500 men,

divided into three parties. Each attacked a separate post, while a fire

was kept up in their favour form every point, the Puntal, the west

bastion, the lines, and the ships in the harbour. After a short

resistance, they were all forced back with the loss of 400 men, besides

many who, in the hurry of retreat, precipitated one another into the

ditches, and were drowned. The loss of the besiegers in killed and wounded

amounted to fifty men.

In the afternoon of the

30th two mines were sprung with such effect, that a practicable breach was

made in the bastion, and orders were immediately given for the assault.

The troops mounted the breach, entered the fort, and formed themselves

with such celerity, that the enemy were confounded, and fled on all sides,

leaving 350 men killed or drowned by leaping into the ditches, while 500

threw down their arms. Don Lewis de Velasco, the governor of the fort, and

the Marquis Gonzales, the second in command, disdaining to surrender, fell

while making the most gallant efforts to rally their men, and bring them

back to their posts. Lieutenant-Colonel James Stewart, [This officer

served afterwards in India, and commanded against Cuddalare in 1782. He

was son to Stuart of Torrance.] who commanded the assault, had only two

lieutenants and 12 men killed, with 4 sergeants and 24 men wounded.

Thus fell the Moro, after a

vigorous struggle of forty days from the time when it was invested. Its

reduction, however, was not followed by the surrender of the Havannah. On

the contrary, the Governor opened a well-supported fire, which was kept up

for some hours, but produced little bloodshed on either side. The

besiegers continued their exertions, and erected new batteries against the

town. After many difficulties and delays, in the course of which the enemy

exerted themselves to intercept the progress of the batteries, the whole

were finished on the morning of the 13th August, when they opened with a

general discharge along the whole line. This fire was so well directed and

effectual, that at two o'clock in the afternoon the guns of the garrison

were silenced, and flags of truce were hung out from every quarter of the

town, and from the ships in the harbour. This signal of submission was

joyfully received, and on the 14th the British were put in possession of

the Havannah nine weeks after having landed in Cuba. It was agreed that

the garrison, now reduced to less than 800 men, should, in testimony of

esteem for their brave defence, be allowed all the honours of war, and be

conveyed to Spain with their private baggage. Nine sail of the line and

several frigates, with two seventy-fours on the stocks, were taken;

several more had been sunk and destroyed during the siege. The value of

the conquest altogether was estimated at three millions. This estimate,

however, could not have been correct, as the prize-money divided between

the fleet and army in equal proportions, was only 736,1852. 2s. 4½d. The

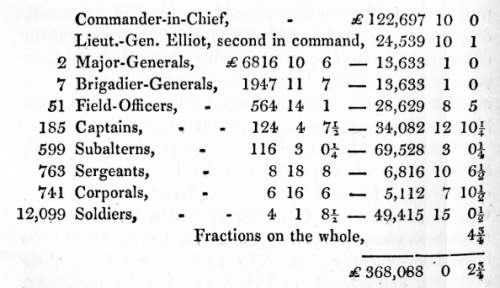

distribution to the land forces was,

This important conquest was

effected with the loss of 11 officers, 15 sergeants, 4 drummers, 260 rank

and file, killed; 4 officers, and 51 rank and file, who died of their

wounds; 39 officers, 14 sergeants, 11 drummers, 576 rank and file,

wounded; and 27 officers, 19 sergeants, 6 drummers, and 230 rank and file,

who died by sickness. The Highland regiments suffered little. The loss

sustained by the two battalions of the 42d regiment was 2 drummers, and 6

privates killed, and 4 privates wounded; the loss by sickness consisted of

Major Macneil, Captains Robert Menzies, brother of the late Sir John

Menzies, and A. Macdonald, Lieutenants Farquharson, Grant, Lapsley,

Cunnison, Hill, Blair, 2 drummers, and 71 rank and file. Of Montgomery's,

Lieutenant Macvicar and 2 privates were killed, and 6 privates wounded;

and Lieutenants Grant and Macnab, and 6 privates, died of the fever.

[The King of Spain

expressed great displeasure at the conduct of the commanders who

surrendered the place. Don Juan de Prado, the governor, and the Marquis

del Real Transporte, the admiral, were tried by a council of war at

Madrid, and punished with a sequestration of their estates, and banishment

to the distance of 48 leagues from the Court; and the Viscount Superinda,

late viceroy of Peru, and Don Diego Tavanez, late governor of Carthagena,

who were on their passage home, and had called in at the Havannah a short

time before the siege, were also tried, on a charge of assisting at a

council of war, recommending the surrender of the town, and sentenced to

the same punishment. But the conduct of Don Juan de Velasco, who fell in

the defence of the Moro when it was stormed, was differently appreciated.

His family was ennobled, his son created Viscount Moro, and a standing

order made, that ever after there should be a ship in the Spanish navy

called the Velasco.]

Immediate preparations were

made for removing the disposable troops from the Island. The 1st battalion

of the 42d and Montgomery's were ordered to embark for New-York, where

they landed in the end of October. All the men of the 2d battalion, fit

for service, were drafted into the 1st; the rest, with the officers, were

ordered to Scotland, where they remained till reduced in the following

year. All the junior officers of every rank were placed on half pay. |