|

FORT LEAVENWORTH

FORT

LEAVENWORTH, was founded in 1827 and is situated on a

strategic bend in the Missouri River – on whose banks

you can still discern the ruts made by the wagons of the

earliest settlers if you know where to look – and it’s

where as previously stated the US Army Command & General

Staff College (henceforth USACGSC) is located. The

contiguous county town of Leavenworth, to which the Fort

has given its name, is a typical small mid-western town

of roughly 36,000 souls.

Leavenworth’s main claim to fame is the number of

prisons it boasts, including the federal US

Penitentiary, Leavenworth, and the US Disciplinary

Barracks, the US Army’s only maximum security prison.

Although these institutions give the town a somewhat

severe façade, it is a pleasant place to live and work,

and not too far from Kansas City for those who seek a

bigger environment and brighter lights.

Rather naively I had assumed that being a fort it would

have a guarded perimeter, or perhaps even a traditional,

historic palisade curtilage like those featured in every

western film you have ever seen, but not so. It is more

of a cantonment than a fort, at least it was in those

pre-9/11 days, and open on all sides. It is also home to

several other US Army schools and colleges and has the

reputation of being “the intellectual center (sic) of

the US Army”.

Holding the Union Flag at the course opening ceremony.

Where do

I begin to describe the US Army staff course? Well, for

starters, there were 1,280 students on the course I

attended, about ten times the number of the equivalent

British course then at Camberley. The vast majority

were, unsurprisingly, Americans drawn from all four of

their services – Navy, Army, Airforce and Marines. We

“International Students”, as we were called, numbered

about 70 if I remember correctly and I was the sole UK

representative. The course also included the first

Russian and first Ukrainian army officers, part of the

general rapprochement following the dissolution of the

Warsaw Pact.

The course itself followed the usual curriculum on

doctrine, tactics, and leadership and was taught mainly

in small syndicate groups of about ten, presided over by

a US Army Lieutenant Colonel (British abbreviation Lt

Col, American LTC; don’t get me started on Americanisms

… ). I have to say I was very impressed by my new

American colleagues on the whole. They were professional

if a tad serious but were good at what they did. There

was an enormous amount of reading doled out as part of

the course, and I warmed to them even more when one of

them whispered in class to me “it’s only a lot of

reading if you actually do it”. My sort of people!

There were, of course, many aspects that I found quite

amusing, in a laugh-with-them rather than a

laugh-at-them kind of way. One that struck me straight

away was that it was impossible for me at first to

distinguish very senior officers from my lowlier

compatriots. They all wore the same uniform, and

sometimes the only indicator of rank would be a discreet

five stars (that’s pretty senior by the way) hidden on a

rank slide on a uniform indistinguishable from everybody

else’s. Addressing the US Army’s Chief of Staff as

“mate” as you politely ask him to get out of the way is

not seen as best practice, not in anyone’s army, but you

couldn’t tell.

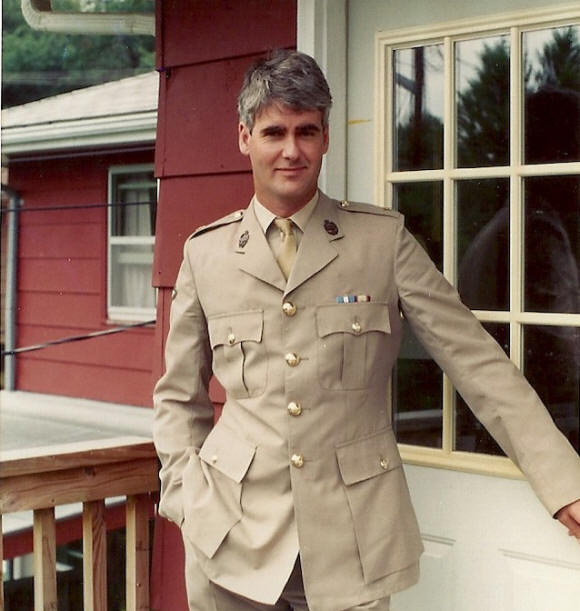

Moi, in my tropical service dress on the back porch.

They also

had a pathological fascination with getting their hair

cut. The onsite barbers seemed to be at it day and

night, with queues of US Army officers outside its door

waiting for their already extraordinarily short hair to

be coiffed even shorter. It was a bit like a skinheads’

convention at times, without the big boots and tattoos.

Meanwhile we Europeans were swanning around the campus

in our strange and outlandish uniforms tucking our

flowing locks into our berets. To be honest, much of the

time I made my uniform up; whatever was comfortable or

clean would do in any combination. Who knew otherwise?

The hours that many of them kept were also a source of

constant amazement. It was not unusual for the US

students on the course to be in work at 5 am, which was

close to when some of the International Officers were

just going to bed. In the evening they would turn in at

9.30 pm, which was before many of us had had our evening

meal, ready to get up fresh and eager for the next

working day. Just couldn’t understand it, but each to

their own I guess.

But I must say again just how welcoming, pleasant, and

kind our hosts were. And they too must have been amused

by us much of the time. When at work my American chums

seemed to be unfazed by anything they were asked to do

or any role they were asked to play. Tell a British

student at one of the UK staff colleges at a map

exercise that they’re to fill the role of Corps

Commander and they’ll have kittens; tell an American the

same thing and they’ll deal with it exactly the same as

they would if asked to command a platoon. They were, and

probably still are, much more comfortable at scale than

we are.

We had a couple of trips within the USA as part of the

course and they were good fun; not quite as hedonistic

as similar trips undertaken by the British staff college

back in the day but fun nonetheless. The detail is lost

to me now, but I do remember one aspect of a trip to

Washington DC, where we visited the Pentagon and similar

institutions. One of our number, a Kiwi SAS officer and

serious rugby player, took great delight in saying to

everyone we met in the streets wearing a back-to-front

baseball cap – which was virtually every male under

twenty-five – “excuse me, do you realise you’re wearing

your hat the wrong way round?”, which provided endless,

childish amusement. Looking at him it was clear that

no-one was going to object.

The house I rented in Leavenworth complete with a Lion

Rampan

There was

much greater emphasis on the reading of military history

than there had been at Camberley as far as I can

remember. Our first piece of required reading was The

Killer Angels, a historical novel by Michael Shaara that

was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 1975. The

book depicts the three days of the Battle of Gettysburg

during the American Civil War, much of it told through

the real life character Colonel Joshua Lawrence

Chamberlain of Maine, whose 20th Maine Volunteer

Infantry Regiment held the left of the Union line during

the battle and whose defence of a feature known as

Little Round Top was critical to the defeat of the

Confederate Army.

We visited the battlefield, and stood on Little Round

Top, which was a sobering but fascinating experience. I

was also able during my time in Leavenworth to research

and present to my classmates on the Battle of Caporetto

(aka Twelfth Battle of the Isonzo) in 1917, a heavy

Italian defeat at the hands of the Germans and

Austrians, of particular interest to me as my

grandfather had been there. Few people realise that

there were British troops fighting in Italy in the First

World War, but there were. My grandfather was part of an

all volunteer medical unit which he had joined with all

his pals, as they did in those days. Typically, he never

spoke very much about it, except to say that he had been

“the first man in the retreat” and his Italian comrades

had all thrown their rifles in the canal and run away.

Perhaps they had learned that a German officer called

Rommel was one of those attacking them!

The senior American officers who came to speak to us

were very impressive. Many of them had served in the

Vietnam War and were grizzled old veterans, and some had

also been involved in Desert Storm in 1991. They tended

to bounce on to the stage in the vast central auditorium

deep in the college and shout out the name of the

syndicate they had been part of when they had attended

in the past. This usually resulted in the current

iteration of that syndicate jumping to their feet and

shouting “hooaah!” in the way that American soldiers

tend to do. It was great theatre, and the generals were

great speakers, much better than their British

equivalents in my opinion.

The course was overall a very busy and comprehensive one

and thoroughly enjoyable for me and my fellow

International Officers. It wasn’t all work, of course,

and away from the course there were a myriad of other

social, sporting, and cultural events which went on.

Some of them were great fun to take part in and showed

colourful aspects of mid-Western life which were, in

some cases, not too far from the Hollywood images so

familiar to all of us. I’ll write more about this in the

next episode.

To come in Part 33; living and working (and playing) in

Kansas (continued).

Photos by

the author. |