|

AND SO

1991 ARRIVED and found all of us at Headquarters British

Forces Middle East (HQBFME) in reasonably good spirits.

By now we realised that the chances of resolving the

crisis in the Gulf without going to war were slipping

away. With nearly 430,000 US troops in Kuwait Theatre of

Operations (KTO) and Saddam Hussein threatening to

attack Israel, it seemed that there was little room for

diplomatic manoeuvre left.

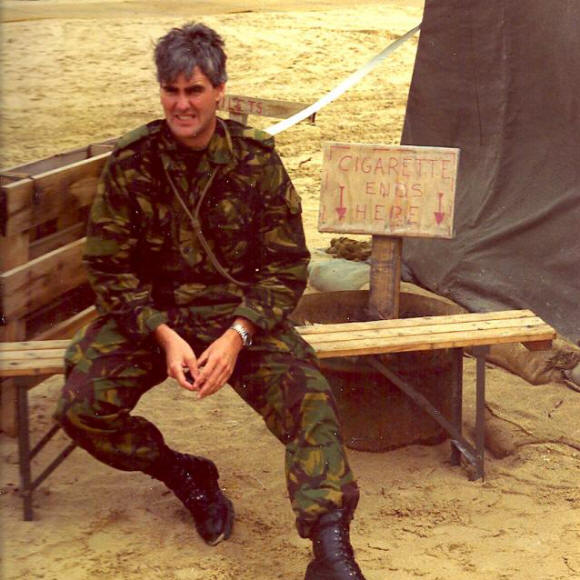

Actually the New Year was nearly a very short one for me

(pictured above at al Jubail airstrip). Travelling down

the motorway to visit Div HQ in the desert we had a blow

out in our car at 100 mph. It was exciting at the time

but the driver managed to keep control, aided by the

fact there was no other traffic on the road. Got the

heartbeat up a bit but otherwise we were OK.

The desert was… pink! Did you know that? I always

thought it was a sandy colour but the bit I saw was

definitely pink. Which might explain why the SAS, who

are well hard and not generally associated with girly

colours, tend to paint their vehicles accordingly when

involved in desert ops. Who knew? I didn’t, but now I’ve

seen it with mine own eyes I understand.

But I digress. The desert was absolutely covered with

military kit. As far as the eye could see there were

vehicles static and moving, tented camps, supply dumps

and all the other paraphernalia that signifies a major

military operation. It took some time to locate Div HQ

as signposting wasn’t a major success and one tented

location looked just like the others. I found it

eventually, but it was in the middle of an NBC exercise

and everybody was masked up and in their noddy suits. I

put my stuff on to conform, but communications were nigh

on impossible. It was farcical to be honest.

When the exercise ended and we all got back to normal I

did my rounds of the various desks to ask what people

needed. At the end of the day I went for dinner in the

HQ mess tent, noting with much amusement that the guards

on duty had already all gone a bit native and were

dressed in a combination of British temperate and desert

combats, bits of American kit they had swapped, and the

bright pink Saudi shemaghs that the locals favoured.

Nobody paid a blind bit of notice, perhaps because

historically the British army has always seemed to go a

bit T E Lawrence in the desert.

Queen’s Own Highlanders formed the guard at HQBFME

After an

uncomfortable night in some temporary hut, sharing with

a sergeant-major who complained bitterly that “he hadn’t

joined up for this sort of thing”, I made my way back to

Riyadh. At that time, and maybe it also applies now, I

thought it the most soulless city I had ever visited. It

was as if vast wealth had suddenly come to a backward

and mediaeval people and they had decided to spend it

all on aping their idea of American culture. Oh, hang on

a minute…

Back at HQBFME our spirits were hardly lifted by a visit

by the Prime Minister, John Major, of whom some of you

may have heard previously. If you haven’t don’t worry

because you haven’t missed anything. He came and gave a

little morale-shattering (boosting, surely?) speech to

the staff, but I couldn’t be bothered going next door to

listen to a stream of well-intentioned but mindless

platitudes, and so I caught up with my paperwork

instead. To be fair, nowadays it would be Boris Johnson

visiting, so we must be thankful for small mercies.

On 12th January 1991 we went on to 24 hour manning and I

was designated to join the nightshift on the Land Cell

operations desk. Things became noticeably more serious

at this point; the Americans started wearing helmets and

body armour and our guards from the Queen’s Own

Highlanders became doubly vigilant. Worst news for many

was that, there now being sufficient numbers in HQBFME,

we now qualified for a catering unit and therefore

subsistence allowances were to stop. As the unit’s gravy

train arrived our own personal one came to an end.

Richard Aubrey-Fletcher

Richard Aubrey-Fletcher

I shared

the nightshift with Richard Aubrey-Fletcher and Henry

Spender, both nice chaps, and we all got on well.

Generally speaking there was much less to do at night

although we were to have some excitement in the weeks

ahead. Working through the wee small hours was a bit

strange to begin with, and we all found it extremely

difficult to stay awake initially. However, after a few

nights our body clocks adjusted and we were fine. Just

as well, for we were to be on constant nightshift for a

couple of months.

Much of our time began to be taken up answering some

rather basic detailed questions from Joint Permanent HQ

(JPHQ) at High Wycombe back in the UK, the pettiness of

which began to irritate us. It was, in retrospect, a

sign of how little they had to do and how left out of

the picture they sometimes felt. We tried to explain

that there wasn’t actually all that much going on in

Saudi Arabia, but they never quite believed us and

always thought we were hiding something. I was taken to

task once for not reporting the discovery of a hand held

rocket launcher on the beach, such was their thirst for

information, any information. Did it mean that Iraqi

special forces had landed behind our lines they asked?

Did it Hell I replied, probably one of our allies had

forgotten about it after a swim.

It was clear though that time for a peaceful solution

was running out fast. We got to the point where the

Iraqis couldn’t actually get out of Kuwait within the

parameters set by the UN resolution even if they’d

wanted to. I was still unaware of any plan to oust the

Iraqis from Kuwait but I guessed that some of my

colleagues were better informed than I. It didn’t take

the brains of an Archbishop to work out that any

operation would probably start with some sort of air

attack, but that’s about as much as I had thought about

it. We all knew it was coming soon though.

The night shift reported for work at 2130 hours on the

night of 16th January ’91 and we were instantly aware

that something was going on. Nobody said anything, nor

was there anything out of the ordinary happening, but we

could feel that the atmosphere was quite different.

There was something intangible about the place, an

unspoken anticipation that set us all on edge. We went

for “lunch” at midnight as usual, a meal taken outside

the HQ in a lean-to shed in the back yard where the RAF

cooks produced standard forces fare which had come as a

welcome relief after our first few weeks’ existence on

Wendy Burgers and little else.

As we munched on our sausage and chips I was aware that

there was a seemingly endless succession of aircraft

taking off from the airport nearby. I mentioned this to

Richard A-F, who looked at me in a funny way and said

that he thought that maybe “something was going on”. At

that point I knew that he knew, and that I was about to

find out.

Sure enough, I was back at the Land Cell Ops desk at

0150 in the morning when the Assistant Chief of Staff

Ops (ACOS Ops) announced that US forces had just

launched 100 cruise missiles at Iraq. We were briefed

formally at 0200 hours that hostilities against Iraq had

commenced. At long last the air war had started.

As it turned out, we were being briefed just as the

first raids were starting, although we learned that US

special forces had gone into action some time earlier to

neutralise some Iraqi radars thereby allowing coalition

aircraft to cross the border undetected. Suddenly aware

that it was all happening, we turned to the television

with a kind of awful fascination to confirm what we had

just been told.

Lockheed F117As lined up - if your eyes used radar you

wouldn't see them.

Lockheed F117As lined up - if your eyes used radar you

wouldn't see them.

CNN was

broadcasting live from Baghdad and we were treated to

the mother of all fireworks shows as every Iraqi gun

blasted blindly into the night air, not being able to

detect the US F117A Stealth Fighters that were bombing

their city. Back in Riyadh we then embarked on a series

of air raid and NBC warnings which had us struggling in

and out of our NBC suits. Nothing actually came our way

that night, of course, but it did add to the excitement

of the occasion!

It wasn’t too long before the Iraqis fired back at us,

but that will have to wait until the next episode, in

which I detail the personal and very important part I

played in Saddam’s downfall.

To come in Part 23; SCUD raids on Riyadh. |