|

WHEN I

REJOINED 4th Tonks in early 1989 it was still in

Osnabruck. I had visited the Regiment once, I think,

over the past four years and it was less familiar to me

although only some of the personalities had changed. The

Officers’ Mess, though, was quite different. A whole

generation of young subalterns had joined, and many had

already left having completed their Short Service

Commissions, during the time I had been away. I also

found that I was now the most senior bachelor officer

which was distinctly odd.

The good news was that the Regiment was now commanded by

Lt Col (later Brigadier) Charlie McBean, a fellow

Glaswegian, and his adjutant was another Scotsman,

Archie Lightfoot from South Uist, so we really did live

up to our claim of being “Scotland’s Own Royal Tank

Regiment”. I was given command of C Squadron, where my

2ic was Patrick Kidd, who went on to become a Brigadier

in the Australian Army, and the subalterns were Hamish

De Bretton Gordon (DBG, now the media’s go-to expert on

all aspects of chemical and biological warfare), Sean

Rickard, a Kiwi, Charlie Pratt (now Cavanagh) and Brett

Fleming-Jones. They were all nice boys and I liked them

a lot. I think Patrick probably thought I was a bit

casual and a soft touch discipline wise, and he may have

been right. After all, he’s the one that made Brigadier,

not me!

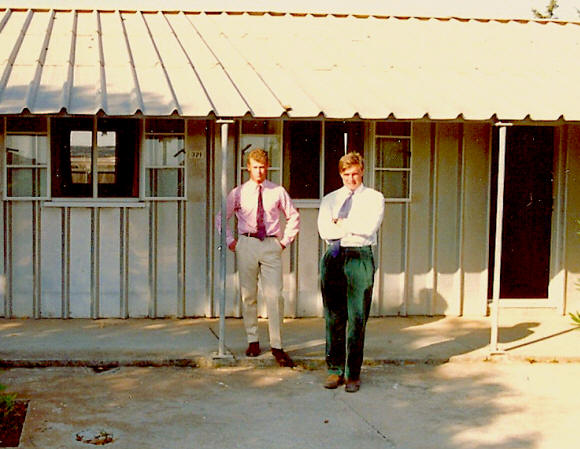

Charlie Pratt and Hamish De Bretton Gordon

It’s an

old adage that the senior NCOs were, and no doubt still

are, the backbone of the British army, and that was

definitely the case in C Squadron. Mine were an

outstanding bunch; I couldn’t have wished for a better

SSM than WO2 Stuart King, nor in my SQMS Davy Valley.

Troop Sgts came and went a little during my time in

command but included John Barnwell, Sinky Sinclair,

Jimmy Simpson (now McCalman), John Riach, Murdo McLeod

and “Jack” Russell. They were the ones who kept the

whole thing ticking over smoothly and they were a fine

bunch.

SQMS Davy Valley and crew

I arrived

back at the Regiment just in time to participate in our

UN tour of Cyprus as dismounted infantry. This was meant

to be a jolly, a holiday posting for all of us after

eight years of BAOR grind on panzers. Consequently, in

early 1989 we put our tanks into the hangars and started

re-learning the basic infantry skills we had all gone

through in basic training. Out went our Sterling

sub-machine guns (SMGs) and in came the Belgian designed

self-loading rifles (SLRs), bigger, longer, heavier and

infinitely more powerful. They allowed the old sweats to

swing the lamp about previous Norn Ireland tours where

they had last used them.

4th Tonks had always been reasonably fit; we held two

regimental runs a week on top of other voluntary sports

activities. But we commenced trying to get infantry fit

with a series of route marches carrying rifles and

webbing, and it was surprising how many of the younger

lads found this difficult. We got there in the end,

though. Then at some point we had to pass our Annual

Personal Weapon Test (APWT) on the SLR. The final bit of

preparation was the CO’s exercise to confirm our

infantry skills in a series of advances, attacks, and

patrols out in the field.

The “field”, in this case, was literally that, German

farmers’ fields in the monotonously boring northwest

German plain. Depressing at the best of times in late

winter/early spring, they were made much worse by the

near constant rain and the farmers’ habit of spreading

untreated pigs manure on them to encourage growth. As

the correct response to coming under effective enemy

fire is “down, crawl, observe, fire”, you can imagine

how popular that was in the circumstances. We stank to

high Heaven and were only too glad when it ended.

And then in June of that year we went to Cyprus. I can’t

actually remember how we got there but obviously we

flew. I do remember the CO getting mightily hacked off

with the RAF for making us wait around for come

considerable time before we set off, a recurring theme

during my military career. We hated RAF movements, who

we thought lax, scruffy, rude and inefficient – which

they were. Anyway, eventually we landed in RAF Akrotiri

and wended our way up to Dhekelia in the Sovereign Base

Area (SBA), where C Squadron was to spend the first

three months of our six month tour before moving up on

to the UN Green Line.

Soldiering in the SBA was like being back in the days of

the Empire. We were nominally guarding the base, but in

fact there was no enemy, and the boys got quickly bored

stagging on despite a few training exercises thrown in

to keep us occupied. The Base Commander was clearly

bonkers, perhaps having spent too long in the sun. It

was his habit to turn up at 3 am in the wee small hours

in full dress uniform to inspect the pillboxes our

sentries manned 24/7, probably to try and catch them

sleeping on the job. We despised him for it.

Marlita beach

It was

blooming hot too, and we worked from 6 am until 2 pm and

then packed it in for the day. Our barracks were on the

beach, and for the first fortnight the sea was full of

white, skinny Scottish soldiers frolicking about as if

on holiday in Torremolinos. After that initial burst of

enthusiasm few bothered any more. We spent time at the

nearby “Larnaca strip”, a collection of dingy and

dilapidated bars, restaurants and clubs which ran along

the coast road, and dined on a standard and repetitive

menu of “mezes” (a selection of small dishes served as

appetizers) until we could stand them no more. In the

Officers’ Mess (main picture) brandy sours were the

drink of the tour for reasons I know not – cheap brandy

I would presume. They were very refreshing anyway.

To be frank, southern – that is Greek – Cyprus was a

mess at that time, all dusty roads and half-finished

buildings with the beginnings of the modern tourist

trade which now defines it. The British expats were

awful people and we tried to have as little to do with

them as we could. The British holidaymakers even more

so. I did spend some time, though, visiting some of the

ancient ruins on the island which were quite impressive.

There was also a rolling programme for R&R which meant

that we were never completely up to strength at any one

time. Lots of the boys took the boat trip to Egypt,

which by all accounts was a bit of a booze cruise,

whereas the officers tended to go home or bring their

WAGs over to the island for a fortnight or longer.

At some point we went up the long, narrow extension to

the SBA which led up to the listening station at Ayios

Niklaos, just short of the deserted former holiday

resort of Famagusta which was in the middle of the

no-man’s land between Turkish and Greek Cypriots. What

allegedly goes on here can be found via Wikipedia but

suffice to say there seemed to be a large number of

civilian employees on site and in the Officers’ Mess

there, many of whom seemed to be Arabic speakers. I

can’t for the life of me think why that should have been

the case, but there you go.

The six odd weeks we spent there were doubly dull. The

boys once again stagged on guarding the barracks and

manning a check point that led into nowhere and whose

traffic mainly consisted of locals going to their

fields. There was yet another dingy roadside restaurant

serving the local fare there and not much else. I think

it would be fair to say that we were pretty bored there,

even more bored than we had become back down in Dhekelia.

It was tedious in the extreme.

How to sum up our time spent in the SBA at Dhekelia?

After the initial frisson of excitement of the new it

was pretty humdrum. We were there because we were there,

but it certainly didn’t turn out to be the holiday

posting we imagined. In our boredom and ignorance we

were almost looking forward to going up on to the Green

Line as part of the UN. We should have been more careful

about what we wished for, but that can wait until next

time.

To come in Part 18; on the Green Line with the UN.

|