|

AND SO TO

RANGES, or firing camp as some other regiments called

it. This happened once every year or two years depending

on which particular training cycle you found your self

on. We took it very seriously, as all good regiments

did, because unlike manoeuvre training where your

performance could rest on the opinion of the senior

officer present, on the ranges your performance was

easily measurable by the number of holes you put in the

target and the time it took you to do it. So were on our

mettle and, for those horrified by the bacchanalian

excesses recounted in the last episode, there was nigh

on no alcohol either, during working hours at least.

Training started in camp on various training aids which

simulated the real thing. My first year I hadn’t

completed my troop leader’s course before I joined the

Regiment and so, quite rightly, wasn’t entrusted to

command a tank at ranges. However it was thought a good

idea that I should be the squadron 2ic’s loader during

firing, which was good experience before going off to

Lulworth in Dorset where gunnery training takes place.

Initial loaders’ training took place in a “SIM”, a sort

of open plan, tank turret mock-up with a pretty faithful

working reproduction of the gun breech crew stations,

and ammunition stowage.

Of course the practice ammunition was inert, which is

just as well because in my very first attempt at the

loader’s drill I dropped the round – I hadn’t expected

it to be so heavy! As the only officer in my class of

about eight there was much smirking and tittering from

the rest, but it was much warranted. I didn’t drop one

again. Meanwhile the commanders and gunners went through

their own simulator the name of which I have forgotten

but ended up with airgun pellets being fired at rubber

tank targets in a sand box on a miniature range.

Sophisticated it wasn’t, and I guess it must have been

of Second World War vintage at least.

Anyway,

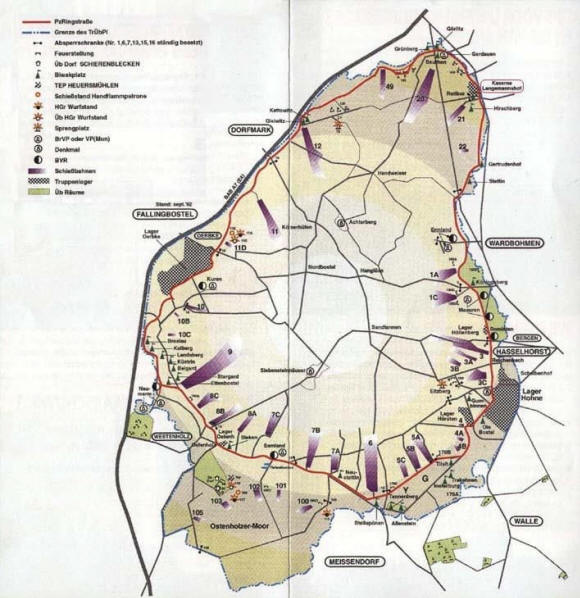

after a few weeks’ build up we would then embark en

masse for Hohne Ranges (above) just up the road, tanks

and drivers by rail or transporter and rest by road.

Nowadays I understand that, under some scheme called

Whole Fleet Management (WFM), you only have a few tanks

for training in barracks and the rest you sign out like

hire cars for field training and ranges. None of that

back in the day, we owned our own tanks and took them

with us (Canada excepted) for training.

The loading up of our tanks in barracks if we were going

by road brought a little bit of post war history with

it. One of the tank transporter regiments was formed by

the “Mojos”, members of the British Army of the Rhine’s

(BAOR) Mixed Service Organisation (MSO) comprising

former PoWs and Displaced Persons who either couldn’t or

wouldn’t return home at the end of the War. Many of them

were Poles who did not wish to return to their home

country whilst it was under communist rule.

Anyway, when it was time to load up the Mojos would roar

into barracks in their huge tank transporters and do the

circuit, and as each one passed a tank would fall in

behind and follow it round until they were all in. The

tanks would then load with much roaring on engines, and

then head out straight away, or perhaps camp for the

night on the barrack square before making the journey.

Our tank drivers went with them in their cabs. The Mojos

had their own rank structure and customs and were expert

at their job, not surprising perhaps as some had been

doing it for well nigh 40 years by then. They were also

fiends for their schnapps and slivovitz at any time of

the day or night and Herculean smokers. As for their

food, well, best not ask!

Eventually, after the odd hiccup here and there,

personnel and tanks would meet up at Hohne. The tanks

would be parked up and guarded on the firing point(s)

and the rest of us would pile into our accommodation in

the camp proper. To be honest I can’t remember much

about our living arrangements except it was typically

Teutonic, hardly surprising as our predecessors had been

at one point the Wehrmacht and Waffen SS tank battalions

of Nazi Germany.

Hot Range Firing

It was a

matter of pride to get the first round down range as

soon as clearance was given to fire at 8am in the

morning, weather and range fires permitting. So we got

up at some unearthly hour in the morning (my memory says

4am but that can’t be right, surely?), had breakfast and

were transported out to whatever range we were on in the

open backed Stalwart trucks of MT Troop. Fine, if a bit

nippy, if the weather was OK, not so fine if it was

raining.

On arriving at the firing point there was a flurry of

activity until all was ready. Then we would wait. You

always wait in the army. Sandhurst’s motto “Serve To

Lead” was always amended to “Rush To Wait” at that

gilded institution, and that set the tone for most of my

military career. The RAF transport bods – Crab Air –

were past masters at having their passengers, or “pax”

in Brylcreem Boy-speak, turn up at some unearthly hour

to get their flights, and then making them wait until

pilots and crews had a leisurely breakfast, said goodbye

to their boyfriends and girlfriends, checked out of the

hotels where they had to stay otherwise they’d be “too

tired to fly”, and amble over to the airport. How we

hate(d) them for their lax, matey, lack of discipline

and regard for their temporary charges.

But I digress. The programme tended to be much the same,

for obvious reasons not least of which was new recruits

coming in all the time. First individual tank static

firing, to get the technicalities right and settle the

younger boys down. Then troop firing, when troop leaders

had to control their troops as multiple targets were

popped at the same time. “Alpha this is 41. Yours on the

right, 1500 metres.” “Ah canny – it’s oot o’ arc tae

me!” “Roger, mine then. George, sabot tank on.” “ON!

1350!” “1350 FIRE”. “Firing NOW!” (Bang) “TARGET!”

“Target, stop.” “This is 41B – two targets left, 1300

metres.” “41, got them. Alpha and Bravo split.” And so

it went. Exciting stuff, combined with the “whoomph” of

the 120mm gun and the smell of cordite, the yelling of

the crew over the intercom, and the constant crackling

of the radio from control and the other tanks.

Night Firing at Hohne

Then we

progressed on to battle runs, where we advanced as troop

down the range towards the targets by bounds and the

gunnery staff popped targets as we went. For this we

were closed down and keeping the troop in line (for

safety purposes) and allocating targets was difficult

via narrow vision blocks whilst searching for new

targets at the same time. The gun was stabilised in

azimuth and elevation so we could shoot pretty

accurately on the move, but it made the loader’s task

all the more dangerous as the breech swung up and down

as we bounced down the range. If the staff popped some

men-sized targets we then had to shift to engaging with

the co-axial machine gun, and the turret would fill with

cordite fumes. If you weren’t careful they could

temporarily asphyxiate your loader and you’d look round

to find him unconscious on the turret floor.

Dangers aside, however, it was great fun and we were

quite good at it. There were always amusing incidents.

Every so often someone would get a hangfire, when

instead of a bang as the round went off there would be a

fizzing sound, often accompanied by smoke coming out of

the breech, as the charge decided whether to go off or

not. Usually they went off after a few seconds, but

occasionally they didn’t go off at all, and then you

were into the whole misfire drill followed by a wait of

30 minutes before you could open the breech. This latter

event was always approached with a certain amount of

trepidation as there was always a chance that the inrush

of air would set off the charge and it would blow back

into the turret and roast everybody in it. Thankfully it

never happened in my time, although I did witness a crew

so frightened by the hiss and smoke of a hangfire that

they all bailed out and stood on the back deck of their

tank, whereupon the gun fired and the round went off

downrange. It was the only time I saw an unmanned tank

fire.

To come in Part 10; Canada.

© Stuart Crawford 2020 |