|

IT’S THE

SEVENTH episode of this never-ending saga and only now

am I turning to tanks and what it was like being a tank

soldier in the last two decades of the 20th century,

which tells you something in itself. But before I go

there, I have to say that some of my comments about our

sister regiments, 1, 2 and 3 RTR have been taken the

wrong way. They were very fine regiments in their own

right and had marvellous officers and soldiers. The fact

we in 4 RTR felt we didn’t have all that much in common

with them was hardly their fault, more the fault of RHQ

RTR. So, if I have upset anyone, that was not my

purpose, and I am sorry. I have every respect for anyone

who has served in any tank or cavalry regiment. Honest.

Anyway, tank soldiers – the Americans call us “tankers”

which is an ugly word and another example of the

creeping Americanisation of British culture which must

be resisted at all costs – are a breed apart. If you

have never commanded tanks or been part of a tank crew

then you’ll never fully understand. A bit like seeing

Hendrix at Woodstock, – or not, if I can use a musical

analogy. But I’ll try to explain a little of what it was

like.

First of all the vehicles themselves (well, one vehicle

in particular). When I joined 4 RTR the Regiment was

equipped with Chieftain Main Battle Tanks (MBT), mainly

Mk3s and Mk5s if I can recall correctly. D Squadron had

14 of these, with four troops of three and SHQ with two.

My troop, 13 Troop, consisted of three Chieftains and

twelve crewmen including myself, four crewmen to each

tank. A tank crew consisted of a driver, gunner,

loader/radio operator and commander.

The Chieftain has a bit of a chequered history and

reputation. Designed as the replacement for Britain’s

highly successful post war Centurion, it never quite

achieved the fine reputation of its predecessor. In many

ways it might have been too innovative too soon. Great

effort went into lowering the silhouette of the tank

whilst protecting it with the thickest armour, and to

that end the driver drove in a supine position (when

closed down) on a reclining seat, looking through

periscope sight. The armour was pretty thick too,

presenting roughly 15.5 inches of armour to horizontal

attack in the frontal arc.

The 120 mm rifled gun was pretty good for the time too.

It was innovative in that, rather than using fixed

ammunition which necessitated the storage or ejection of

spent shell cases, it went down the naval route of

having separate rounds and propellant charges. This

allowed the propellant – the “bag charges” - to be

stowed below the turret ring in pressurised “wet”

containers which would, in theory, prevent combustion

should the tank be penetrated by hostile fire. The

penalty was, of course, that loading two-piece

ammunition, plus the cartridge that fired the whole

sheboodle off, took slightly longer that conventional

one piece ammo. But the gun itself was accurate and we

had every confidence in it.

What let Chieftain down was the engine, which was

forever breaking down. In fact, it was a common saying

that Chieftain was the best tank in the world as long as

it broke down in a good firing position. Sadly,

unreliability of automotive aspects is a recurring theme

in the history of British tank design stretching back to

before the Second World War. The basic problem seemed to

be that it was originally designed to be multi-fuel, an

overcomplication, and originally produced only 650 bhp

for a 56 tonnes tank, so it was chronically underpowered

as well. For comparison, modern tanks have engines

producing up to 1500 bhp.

Breakfast in the Field

This

unreliability made us – or more accurately the boys –

slaves to their tanks, forever working on them,

repairing them, maintaining them. How we envied the

Germans with their Leopard 1s, who parked them up on a

Friday, went home for the weekend, then started them up

on Monday morning and off they went. Yes, they might

have had thinner armour and a less powerful gun, but at

least they could rely on them to work, and they weren’t

half fast as well.

But, while I don’t think we ever came to love our

Chieftains, we did sort of like them. Sure, they were

demanding masters, but when you got them to work as

designed they were sweet to be in. Unlike the young men

of the Royal Armoured Corps nowadays, we got to take our

tanks out a lot on exercise, or “scheme” as the boys

called it. A troop leader could still decide to take his

troop out to the local training area if he could

persuade the squadron leader it was a good idea, for

example, even though it would involve the RMP and

Polizei stopping the traffic as the tanks exited the

barracks and headed out on the civvy roads.

That said, it must have been a complete pain in the

backside for the local German population. Our training

area in Munster was a pocket-handkerchief sized training

area know as the Dorbaum, which we used for low level

training or as our “crash out” location when exercising

our deployment plans at short notice, usually when

Exercise “Active Edge” was called[1]. It could happen at

any time of the day or night, and it was not unknown for

Mess dinner nights to be ended abruptly by it, with some

officers deploying still dressed in their mess kit.

The boys on 'Scheme'

To get to

the Dorbaum we had to use the local roads, and many an

incident occurred. Occasionally a tank would throw off a

rubber track pad from its track, a heavy piece of

material, which might bounce off the road and through

the windscreen of a civilian car following. This could,

and did sadly, result in serious injury. Or a tank might

dump all its engine oil on the highway, turning it into

a skidpan with obvious results for local traffic. On one

occasion one of our Chieftain’s brakes failed at the

junction where we turned to head for the training areas

and it ploughed straight on, taking all the traffic

lights out in its path although, thankfully, avoiding

civilian casualties. And, on a more personal note, I

once drove back to barracks with my troop at rush hour,

and the only way I could get past the traffic was by

going up on the newly made pavement, ripping up the

paving stones, much to the annoyance of the German

workers who had laid them minutes beforehand. It was

either that or bring Munster to a halt – what else could

I do?

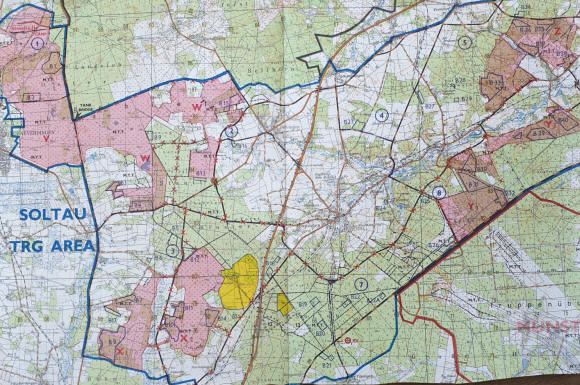

Soltau Training Area Map

Larger

scale manoeuvre training was usually carried out on the

Soltau Training Area up on the Luneberg Heath and close

to where Monty had accepted the German partial surrender

on 8th May 1945. The map above shows its extent – the

red areas being for tank movement – and most of 1 (Br)

Corps had become familiar with it over the past 40 years

or so before I first set foot, or more accurately track,

on it. The old hands had been there so many times they

didn’t even need the map to navigate it, but to a new

boy it could be difficult, especially at night. On my

first night march test as troop leader I got hopelessly

lost, managed to check in at about three of the 10

rendezvous points laid out for us, and eventually waited

until dawn broke to get my bearings. Hardly an

auspicious start, but I was to learn I wasn’t the first

or last to experience such a debacle.

All those years of tracked movement over a relatively

small area had rendered the soil into a fine sand-like

dust, and by the laws on physics (which I was taught but

have forgotten) the open spaces were configured like

waves in the open sea, so that driving your tank across

was a constant rearing and diving motion which

occasionally made people seasick. The sparsely wooded

areas were where we bivvied up at night and slept on the

back decks under tank sheets, not a particularly

pleasant experience in retrospect but at the time we

hardly noticed. Once one of our support three tonner

lorries caught fire and burned out, but the CO just

borrowed a JCB from the sappers, dug a big hole, and

dumped the remains in it before covering over. It’s

probably still there, waiting to be unearthed by some

archaeologist of the future. We weren’t particularly

eco-conscious in those days I’m afraid.

To come in Part 8; the boys, firing camp at the ranges,

and going to Canada,.

© Stuart Crawford 2020

[1] Active Edge could be called at any level, from the

CO wanting to test his Regiment right up to 1st British

Corps (1 BR Corps) crashing out more or less all the

British troops in Germany. |