Death has recently taken two men of the old type, lofty in valour and honour, who founded our Indian Empire. The individual must pass away, but let us hope the type will never be lost, for such men as Donald Stewart and William Lockhart are the true builders of our nation’s greatness. They both belonged to the Bengal Army, and, like Munro, Malcolm, Herbert Edwardes, and Henry Lawrence, were of the great line of statesmen-soldiers who have so materially aided in the establishment and administration of our splendid dependency. Their tact and ability as civilians were only equalled by their ardour and bravery in the field. The story of their lives deserves to be known, for it reminds us by what virtues, and by what toils, a fame so clear and great as theirs is won, and by what thoughts and actions an empire is made and held together.

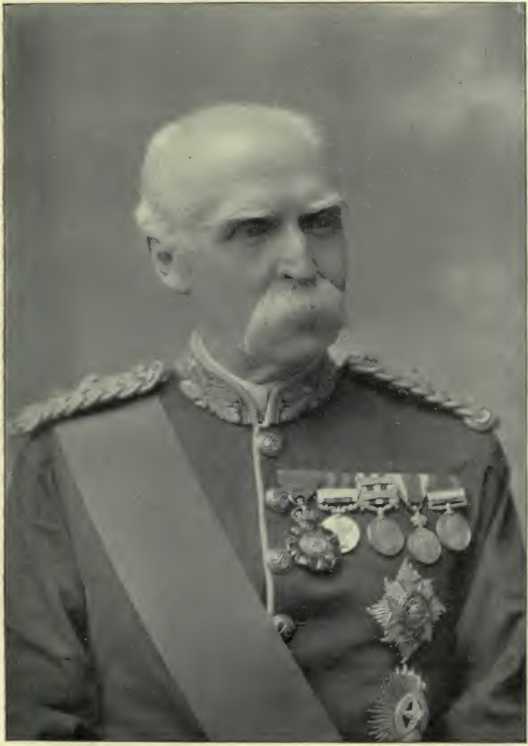

Photo by Messrs Elliott & Fry.

SIR DONALD STEWART.

Donald Stewart and William Lockhart both belonged to the race which has scored so deep a mark in our Imperial history, and were proud of their old Scottish blood. On both sides of his house Donald Stewart was a Highlander, and his strong Norse features and well-knit frame were evidence of his descent. By birth he was a Morayshire man, for in 1824 he came into the world at Mount Pleasant, near Forres. When he was a year old his father, Richard Stewart, moved to Sea Park, also near Forres. And from there Donald was sent, in the first instance, to the village school at Findhorn, a small fishing hamlet near his home, where he picked up the elements of knowledge. Donald Stewart was a product of the old education which formed the character of the English and Scottish nations. At the parish school of Dufftown the dominie not only imparted to him whatever knowledge of Greek and Latin he was able to provide, but he also moulded his character and imbued him with a love of the fine art of salmon-fishing. At the age of fourteen, in order to improve his scholarship before he entered the University of Aberdeen, Donald was sent to the Elgin Academy, then considered the best school in the north of Scotland. The result was satisfactory. He had been there but a year when he gained a small bursary by open competition, and proceeded to the university which has sent to India some of her bravest soldiers and ablest administrators. Before the close of the year, by dint of hard work, he gained a brilliant victory over many competitors. “ My object,” he says, “was to get a fair place at the examination, to please my parents, and I did my best. The result far exceeded my expectation, and no one was more astonished than myself when I heard my name called as the winner of the first prize in Greek and first in the order of merit in Latin. Every one in the class thought it must be a mistake, and my name had to be called more than once before I moved from my seat.”

He adds, “ I was proud of my success, but I had a feeling that it was hardly deserved, as I knew there were many of my term who were infinitely better scholars than myself.” Donald Stewart always did his best, and this was the chief secret of his success ; and all through his life the essentially chivalrous nobleness of his disposition was in no respect more conspicuously manifested than in the modest estimate it induced him to form of his own work, and the enthusiasm with which he acknowledged the soldierly qualities and triumphs of his military comrades.

Not letters but arms were destined to be Donald Stewart’s vocation. His college career came to an end by a nomination to the military service of the East India Company, and in 1840, twelve years before Lord Roberts landed in India, he was appointed an ensign in the 9th Bengal Native Infantry. It was the pattern regiment of that great army whose history abounds with many examples of courage shown in brilliant attack; of courage shown in coolness under danger; of patient stoicism under pain, and self-denying devotion to duty. That the evil that men do lives after them, while the good is often interred with their bones, was amply illustrated in the case of the old Bengal army. But history will record that it was by the aid of the Bengal sepoy the masters of Fort William became the masters of Bengal, and the masters of Bengal became the masters of India. A triumphant mercenary army, however, grew ungovernable; there were not sufficient officers to maintain discipline; and an act of signal imprudence—the issue of greased cartridges—caused a sudden conflagration and explosion. The Indian Mutiny shone with “the sudden making of noble names.” Among these names must be enrolled that of

Donald Stewart. He was stationed at Alyghur, an important station about eighty miles from Meerut and sixty from Agra, when his regiment mutinied. The sepoys plundered the treasury, broke open the jail doors, and released the prisoners; but they did not lay hands on their officers. After his men had marched away in a body to Delhi, Stewart remained at Alyghur and took command of a body of volunteers sent by the Lieutenant-Governor of the North-Western Provinces to aid the civil authorities in maintaining order in the district. But he was too keen a soldier to care for the work, and after a short time he went to Agra and placed his services at the disposal of the Lieutenant-Governor. Despatches had arrived from the Governor-General for the Commander-in-Chief. But all communication between Agra and Delhi was closed. Donald Stewart was told he might be the bearer of the despatches if he chose to undertake so perilous a journey. But no journey was too perilous for Stewart when a duty had to be performed. On the 18th June, as the sun was setting over the broad waters of the Jumna, he set forth on his ride. Darkness swiftly fell. All night he rode, and the sun had risen before he reached the sacred city of Muttra, thirty - five miles distant, without mishap.-Armed men thronged its narrow and tortuous streets; but England’s prestige had not fallen, and they did not attempt to molest the solitary British officer. A Brahmin official received him with courtesy, and offered him two native troopers belonging to a neighbouring chief, to accompany him thirty miles on his road, to the town of Hodul. They were ill-looking swashbucklers, and Stewart would fain have declined their company, but he dared not show any distrust.

At daybreak he resumed his ride, accompanied by his escort. But he had not gone sixteen miles when his horse fell down, utterly worn out. The two troopers laughed and rode away, while Stewart, taking his saddle and bridle, tramped to the nearest village. But no horse could be got for love or money. The future field-marshal siezed a donkey grazing in a field, and at sunset arrived at Hodul, having done thirty-seven miles in the day. The native magistrate courteously received him, and gave him some bread and milk; but he would not hear of his staying one night, as the arrival of a European had created considerable commotion in the town. Stewart was worn by the adventures of the day and wanted rest, but the magistrate was firm, and he at last consented to start if he were provided with a horse. The native promptly lent him his own pony, and Stewart was again under way. Day had long flooded the wide plains when he reached the camp of the prime minister of Jaipur, where he found the political resident and several English refugees. He persuaded one of them, Mr Ford, a district magistrate, to accompany him in his ride. Late on the 27th of June they started forth, and during their journey they passed through towns and villages filled with rebel sepoys breathing death, and once or twice narrowly escaped being attacked by gangs of bandits. The next morning they halted at a village to escape the heat of the day, and they received, as many Englishmen and Englishwomen did in these evil days, much kindness from the villagers. A notorious cattle - lifter guided them all the following night. At dawn they saw “ the tall red minarets of Delhi rise out of the morning mist, when an occasional shell might be seen bursting near the city.” The cattle-lifter refused to proceed any farther. He would take no reward, but he hoped his services would be remembered when quieter times came. Stewart found a villager who conducted them to one of our pickets. A splendid feat of gallantry was done, but Stewart’s modesty has covered the greatness of the deed. Lord Roberts writes: “I was waiting outside Sir Henry Barnard’s tent, anxious to hear what decision had been come to, when two men rode up, both looking greatly fatigued and half starved, one of them being Stewart. He told me they had had a most adventurous ride; but before waiting to hear his story I asked Norman to suggest Stewart for the new appointment—a case of one word for Stewart and two for myself, I am afraid, for I had set my heart on returning to the quartermaster-general’s department, and so it became settled to our mutual satisfaction, Stewart becoming the D.A.A.G. of the Delhi Field Force, and I the D.A.Q.M.G. with the artillery.” As deputy-assistant adjutant-general he took part in that great siege, and conducted the duties of that important department to the satisfaction of the general commanding the field forces, who mentions him in his despatch, and writes of him as “ the gallant and energetic Captain Stewart.” He served in the same capacity throughout the siege and capture of Lucknow by Sir Colin Campbell, and the Rohilkund campaign. On the 30th of December 1857 he was transferred as assistant adjutant-general to army headquarters. For his services in the Mutiny Donald Stewart was rewarded with a brevet majority, and in July 1858 he reached the rank of lieutenant-colonel.

When the old Bengal army disappeared a new Bengal army had to be created, and as assistant adjutant-general from 1857 to 1862 and deputy adjutant-general from 1862 to 1867, Donald Stewart did much towards its formation. His homely sense and careful forethought were of the highest value in adjusting the new system to the varying circumstances to be dealt with. The ability he had shown as a military administrator, and the reputation he had won as a gallant officer in the Mutiny, led to Brigadier-General D. M. Stewart being nominated in 1867 to command the Bengal portion of the force for service in Abyssinia. Major Roberts, R.A., was appointed to be his assistant quartermaster-general. Lord Roberts writes: “I had often read and heard of the difficulties and delays experienced by troops landing in a foreign country, in consequence of their requirements not being all shipped in the same vessel with themselves,—men in one ship, camp-equipage in another, transport and field-hospital in a third, or perhaps the mules in one and their pack-saddles in another,—and I determined to try and prevent these mistakes upon this occasion. With Stewart’s approval, I arranged that each detachment should embark complete in every detail, which resulted in the troops being landed and marched off without the least delay as each vessel reached its destination.” This arrangement has been followed with conspicuous success in subsequent expeditions sent from India.

When the Bengal brigade reached Africa, Sir Robert Napier had already begun his march to Magdala. But before launching his army into an unknown and hostile country he had, like a wise commander, organised his base and provided for his communications. Senafe, 8000 feet above the level of the sea, and distant twenty-seven miles from the port of Zeila, was the secondary base of operations in the campaign, and the great storehouse for supplies and provisions which, after being carried through the Kumayli Pass, were pushed on to the front. Soon after he landed - Brigadier Stewart was ordered to take command of the post, and displayed all the qualities of an energetic and sound administrator. For his services in the expedition he received the Abyssinian medal and a Companionship of the Bath.

On his return to India Donald Stewart was appointed to the command of the Peshawar Brigade. He was no stranger to the great frontier station which guards the Khyber defiles, for his regiment had been stationed there, and he had won his first medal and clasp for distinguished service in two expeditions against the wild tribes on our northern frontier. He held the command of the Peshawar brigade only a short time, as he had to vacate it in December 1868 on promotion to the rank of major-general. Tempting offers of permanent civil employment had been made to him at different times, but he clung to his profession. However, in 1871, an offer was made him of an appointment which required both military and civil capacity.

In the spring of that year it came to the notice of Lord Mayo that a cruel and mysterious murder had been committed in the penal settlement of the Andaman Islands. He ordered a strict inquiry to be made, which disclosed a laxity of discipline productive of scandalous results. He therefore determined to create a new government for the settlement, which, while enforcing stricter discipline, should allow of a career to the industrious and well-behaved. A code of regulations was drafted under his immediate orders, and supervised by his own pen. Then, “true to his maxim that for any piece of hard administrative work ‘ a man is required,’ he sought out the best officer he could find for the practical reorganisation of the settlement.” He chose Donald Stewart. “The charge which Major-General Stewart is about to assume,” wrote Lord Mayo, “ is one of great responsibility. In fact, I scarcely know of any charge under the Government of India which will afford greater scope for ability and energy, or where a greater public service can be performed.”

In the summer Donald Stewart became Chief Commissioner of the Andamans and Nicobars, and at once set to work to carry out Lord Mayo’s scheme, which was a great and .most humane conception. The whole force and earnestness of his character were directed upon the general peace and upon the most subordinate detail. But he had a difficult and delicate work to perform, and he desired that Lord Mayo should “ personally realise the magnitude and difficulty of the task.” The Viceroy resolved to visit the Andamans when returning from his first visit to Burma.

On the 8th of February 1872 Lord Mayo cast anchor off Hopetown in the Andamans. The day was spent in visiting the different convict settlements, and every possible provision was "taken for the Viceroy’s protection. In the evening Lord Mayo insisted on visiting Mount Harriet, a lofty hill about a mile and a half inland from the jetty. He lingered some time on the top watching the sun set in the ocean. “It is the loveliest thing I think I ever saw,” he said. Darkness had fallen when he reached the foot. Preceded by two torch-bearers, he walked down the pier between his private secretary and Donald Stewart, closely followed by a strong body of police. On reaching the stairs, Lord Mayo stepped aside from his companions. In a moment a convict, who had been stalking him all day, rushed out and stabbed him to death. Men of all classes and creeds mourned the death of a Viceroy much beloved, and there was also universal sympathy for the gallant soldier in whose territory the tragedy occurred. But, as the subsequent investigations showed, Donald Stewart had done all that prudence and foresight could suggest to guard Lord Mayo, who, being a strong man full of pluck, had during the day let it be seen that he regarded the precautions taken for his safety as not only irksome but somewhat superfluous. The shock to Donald Stewart was naturally a severe one, and he soon after was compelled to take leave to England to recover his health.

In 1875 General Stewart returned to India, and the following year he was again brought on to the military establishment by being appointed to the command of the Meean Meer Division. In 1878 he was promoted to the rank of lieutenant-general. Early that year the startling intelligence reached India that a Russian mission had visited Kabul, and had been favourably received by the Ameer. A counter-mission was sent, which was not allowed to enter Afghan territory, and war was thereupon declared against Shere Ali, the Ameer. On the commencement of hostilities Donald Stewart was appointed to command the Southern Field Force, destined for the reinforcement of our Quetta garrison and the capture of Kandahar. They had to be pushed forward from Sukkur via Dadur through the Bolan Pass over the Khojak, and at that time there were in those regions no roads worthy of the name. The transport difficulties, aggravated by the death of the camels, were enormous. The loss of life among the unfortunate camp-followers was great, and the sufferings of the troops were unusually severe; but all difficulties were overcome, and on the 8th January 1879 Kandahar was reached without serious resistance having been attempted. Donald Stewart made Southern Afghanistan a tranquil province, and the methods of his administration must always be instructive. He pursued the same policy that Mount-stuart Elphinstone did after the conquest of the Deccan. He did not subvert the existing authority, but he made use of every Afghan official who was willing to render him true and loyal service. A foreign occupation must gall; but he made the yoke fall as light as possible on the shoulders of the people. From Kelai-i-Ghazai to the Helmund British authority began to be respected. Donald Stewart was a successful Governor, not only because he was a shrewd sensible man, but because he was a modest honest man. “ The inhabitants of the city, of the neighbouring villages, and of the country generally,” writes an eye-witness, ‘‘ learnt to know and trust the man who treated them with justice, and always spoke the truth.”

After the treaty of Gundamuk Kandahar was in process of being evacuated; but when the outbreak at Kabul, resulting in the murder of our envoy, occurred, General Stewart was told to reoccupy it. A month after the murder of Major Cavagnari Lord Roberts took possession of Kabul. Then followed the investment of our intrenchments at Sherpur, and the desperate attempt of the enemy to take it, which was foiled by the steady fire of the defenders. Kabul was once again in our hands, and during the winter months General Roberts strengthened his position. In order to overawe more completely the warlike tribes of the north,

General Stewart was ordered to march with the Bengal troops by way of Ghazni to Kabul.

On the 31st of March 1880 General Stewart, leaving Southern Afghanistan to be protected by the Bombay troops, set out to reduce Ghazni and join General Roberts at Kabul. Two long marches from the famous fortress he found, on the 19th of April, the enemy drawn up on a low range of hills through which passes the road to Ghazni. Donald Stewart determined to force his way. He knew that if he stopped to disperse every body of Afghans that gathered on the hills that lined his route, Kabul would never be reached in any reasonable time. He therefore continued his march till the head of the column was within three miles of the enemy; then he began to make his arrangements for the impending battle. Before he completed them the whole upper range, for a distance of two miles, was seen to be swarming with the enemy, and a large body of horsemen threatened our left. Our guns had scarcely opened fire when a torrent of men poured forth from the slopes, and, breaking against our line, spread out right and left and enveloped it. The wave struck the lancers, and forced them back on the infantry. Mules and riderless horses went dashing through the ranks. The fanatics were engaged in a hand-to-hand contest with our infantry. They broke through it on the left, and some penetrated to within twenty yards of the spot where the general and his staff were watching the action. All drew their swords for self-defence. At that critical moment the cool promptitude of Colonel Lyster, V.C., commanding the 3rd Gurkhas, saved us from a terrible disaster. He formed his men into company squares, and poured volley after volley into the fanatics as they surged onwards. The attack had now spread along the line. The general’s escort and the 59th had to fall back. An order issued to this regiment to throw back their right to stem the rush was understood to imply the retirement of the whole regiment, and the movement was carried out. The Ghazis were upon them, and there was a tendency to huddle for common protection. General Hughes, observing this, galloped down, and with a fiery exhortation calmed the men; then by a steady fire they kept the Ghazis at bay, and covered the plain with dead. The fanatics charged with the same desperate valour as the followers of the man of Mecca did when they broke the ranks of the Roman Legion. Beaten back by our force, they returned again and again to the attack. After an hour’s desperate fighting our reinforcements and the heavy artillery came up, and the enemy, finding all assaults hopeless, spread broadcast over the country. Thus ended the battle of Ahmed Keyl, the most hard-fought contest of the Afghan war. Ghazni surrendered without a struggle, and the road to the capital of Afghanistan lay open. General Roberts had sent from Kabul a detachment to co-operate with the Kandahar force, and on April 28th these two forces joined. On the 2nd of May Sir Donald Stewart arrived at Kabul, and, as senior officer, assumed from Sir Frederick Roberts the chief command as well as political control. Sufficient credit has hardly ever been given to Sir Donald Stewart for his daring march from Kandahar to Kabul. But it was undoubtedly a fine feat of arms.

For some time negotiations had been going on between the Indian Government and Abdul Rahman as to his succession to the throne of Kabul, one chief point of difference being that the Government would not recognise his claim to have Kandahar handed over to him. At length all was arranged, and on July 22nd Sirdar Abdul Rahman was formally recognised by the British Government as Ameer of Kabul. A few days after the proclamation of the new Ameer news reached Kabul of the disaster at Maiwand and the investment of Kandahar by Ayub Khan’s army. With the consent of Sir Donald Stewart, Roberts telegraphed at once to headquarters at Simla a proposal that he should lead a relieving force straight from Kabul to Kandahar, and the Viceroy agreed. As Lord Roberts tells us in his * Forty-one Years in India,’ Donald Stewart gave him every possible encouragement and assistance in the organisation of his column. By lending to him his tried troops, he crowned his career in the field by a noble and generous act. After Lord Roberts had left for Kandahar, General Stewart, with masterly skill, marched his troops out of Afghanistan without firing a shot.

For his great military and political services in the war, Donald Stewart received the thanks of Parliament. His sovereign, ever ready to reward the services of her soldiers, bestowed on him the Grand Cross of the Bath, and created him a baronet In October 1880 he was appointed military member of the Governor-General’s Council, and six months after he became Commander-in-Chief in India. The long campaign in Afghanistan had laid bare the deficiencies in our military system; and during his tenure of office were laid by Sir George Chesney—a brave soldier, a great administrator, and a man of genius—the foundations of those military reforms which marked the administrations of Lord Dufferin, and were completed by his successor, Lord Lansdowne. A simple, modest man, Donald Stewart looked at military problems apart from any personal bearing, and the power of taking an unselfish view prevented him from clashing with his colleagues. To make the Bengal army worthy of its old traditions he laboured hard, and when he resigned his command he had done much to make it what it is now, one of the best fighting machines in the world. When he left the land in which he had spent the best years of his life, his connection with India did not cease, for on arriving in England he was appointed one of the official advisers of the Secretary of State. And in the consideration of the numerous political and military problems which from time to time arose his opinion carried great weight, because it was founded on calm judgment and long experience. He worked on till his death, modestly, intelligently, and without fear. The old veteran has gone, but he has left us an example of a noble and blameless career.

It would be difficult to imagine two men more different in their intellect and their character than Donald Stewart and William Lockhart. Stewart was a brave soldier, endowed with a vigorous intellect, Scottish common-sense, and Scottish caution. Lockhart was a dashing captain, full of life and humour, with a strong love of adventure. He possessed in no small degree the brilliant literary instincts of his uncle, John Gibson Lockhart, and his brother, Lawrence Lockhart, gallant soldier and novelist. He had almost every quality fitted to make him a favourite in society. His presence was commanding, his features mobile and handsome, and in every movement there was an air of high breeding and aristocratic culture which bore witness to his old Scottish descent from the “ Lockharts of the Lee.”

Photo by Messrs Bassano.

SIR WILLIAM LOCKHART.

A year after Donald Stewart went to India, William Lockhart was born at Milton Lockhart, where his father was the laird-parson. At the age of seventeen he joined the Bengal army as ensign (4th of October 1858), nominally in the 44th Bengal Native Infantry, but he was attached to the 5th Fusiliers, and shared in the pursuit of the rebels. In 1859 Lockhart joined the cavalry, and the 14th Bengal Lancers, Murray’s Jat Horse, was his regiment for several years. He had been six years in the service when the chance of being employed on active service first came to him. On the 4th December 1863 a mission left Darjeeling for Bhutan, and returned on the 12th of April 1864, having been not only received without honour but even subjected to insult and outrage. War was the inevitable consequence. In the military operations against the Bhutanese, Lockhart, as adjutant of his regiment, first proved himself to be a brave and daring soldier. He had inherited from his Scottish ancestors a keen instinct for scouting and an eye for mountain topography. The services he rendered by his reconnaissance to Cheerung were acknowledged by the Government of India, and he obtained a medal and clasp. The dash and daring he had displayed led to his being appointed aide-de-camp to Brigadier-General Merewether in the Abyssinian expedition. Four future commanders-in-chief of India were employed in that wonderful campaign — Napier, the able commander; Donald Stewart, the brigadier; Roberts, transport officer; and Lockhart, the aide-de-camp,—a group of soldiers of whom any army in the world might well be proud. John Merewether had been one of John Jacob’s most trusted lieutenants, and he managed the various chiefs of Zeila with the same conspicuous success that he had managed the chiefs on the borders of Upper Sind. Merewether reported “very favourably of the services of his aide-de-camp, Lieutenant Lockhart of the Bengal cavalry.” Lockhart was present when the Abyssinians were driven down the slopes of Arogie, and at the subsequent capture of Magdala.

On his return to India, Lockhart was for the first time engaged in one of those punitive expeditions, the need for which will always exist till the other side of the line is held by a civilised government. In July 1868 the Pathans of the Black Mountains attacked a police post, the establishment of which they deeply resented. For four months they raided and destroyed British villages. Then a force of 12,000 men was sent to punish the aggressors. It penetrated without serious opposition to the crest of the Black Mountain, explored the enemy’s country, occupied their strongholds, and reduced them to submission. The work of exploration suited Lockhart. The 2nd Brigade bivouacked for the night at a small village preparatory to the ascent of the Black Mountain the next day by the way of the Sumbulboot spur. Brigadier-General T. L. Vaughan, C.B., who commanded the brigade, determined to reconnoitre that evening the road between the village and spur. “This duty,” he writes in his despatch, “was most ably and resolutely performed by Lieutenant Lockhart, deputy - assistant quartermaster-general attached to the brigade, who at much personal risk reconnoitred for some distance beyond the village of Belean up the spur, and brought me most important information.”

The next few years were spent in carrying on his ordinary regimental duties. But garrison life did not suit his ardent spirit. Not for honour, nor for expectation of advancement, but from sheer love of adventure and a feeling of genuine chivalry, he went forth to pursue and to conquer. It was the unrest in him which led him in 1876 to visit Acheen, where the Dutch were waging a vigorous war against the tribesmen who resented their intrusion into Sumatra. He took part in the assault on Lambada, displayed his wonted gallantry, and received from the Dutch their war-medal and clasp. In the malarious Dutch settlement he was smitten with the cruel blasting fever, and would have been left to die in a shed on the wharf if he had not insisted on being carried on board the Singapore steamer. The sea-breeze restored his health. At the outbreak of the Afghan war he was attached to the Quartermaster-General’s department, and, to his sore disappointment, was left in India. In the second phase of the campaign, after the murder of Cavagnari, he was posted as assistant quartermaster - general with Lord Roberts, and took part in the three days’ hard fighting around Kabul, before we had to concentrate our forces at the cantonment of Sherpur. During the investment Lockhart was the life and soul of the party, who had many a merry evening together in the headquarters of the gateway at Sherpur. For his services during the Afghan campaign he received the insignia of a Companion of the Bath, with, another medal and clasp.

After the war Lockhart went to Simla as deputy quartermaster-general in charge of the newly formed Intelligence branch. But neither the life of the Himalayan capital nor the routine of office-work suited him, and on the expiration of his term of office he assumed command of the 24th Punjab Infantry, and returned to the rugged borderland where he was to win his best laurels. Among the illustrious men, Cleveland, Out-ram, John Jacob, Herbert Edwardes, Reynell Taylor, and John Nicholson, who, from Burma in the far south to Kashmir in the far north, have raised and civilised the warlike tribes on our border, Lockhart has a right to a not undistinguished niche. The mode in which they accomplished their object was in all cases fundamentally the same. It was effected by the power of individual character. They explored the countries beyond the border, and there was no expedition so hazardous that they were not found ready to undertake it. They trusted themselves to the people, and by their courage and frankness they gained their confidence. Lockhart’s great influence among the tribes was due to his good-humoured, confident, fearless way of dealing with them. They felt that they had his sympathy, but they also knew that he was not in the least afraid of them, and that he would not allow them to take the slightest liberty. Like Nicholson, his name was a power on the frontier.

When Lord Dufferin determined in 1885 to send a mission to Chitral, then an almost unknown land, he chose Lockhart to be his envoy. On the 25th of June the mission started from Kashmir, and on the 13th of the following month the Kamri Pass, about 13,100 feet above the sea, was passed. For many miles the road ran through snow. On the 29th of July the mission reached Gilgit. Here it was found advisable to halt for some time, in order that the streams on the Chitral route, swollen by the melting snow, might subside. During their stay the officers of the mission acquired a good deal of useful knowledge regarding the surrounding countries. Surgeon Giles, who accompanied the party, was beset by patients. Among the

operations he performed none excited so much interest as the reconstruction of noses (by a flap from the forehead),—for the deprivation of that organ was a common form of punishment in those regions. On the 8th of August the officers rode out of Gilgit, and the party made their way over roads often passing round the face of a precipice, with the foaming torrent far below. Mules fell over, and the party had to halt to recover the lost loads. Clefts in the face of the rock often broke the continuity of the path, and had to be crossed by a few unfixed logs thrown across, which moved and turned under the foot of the traveller. Over these places animals could not go, and they had to take some higher path which zigzagged over the mountains. Rivers had to be crossed by bridges, primitive and shaky. On the 23rd of August the Shandar Pass, 12,100 feet above the sea, was crossed, and three days later Masting was reached. Here a halt of ten days was made, to await the return of a detached party who had started to explore some of the neighbouring passes. Not till the nth of September was Chitral reached. The mehtar (chief), with the Nizam-ul-Mulk, his heir, and a large following, met the party some four miles from the city and brought them in.

At two miles from the fort [writes Lockhart], the opposite bank of the river was lined by some hundreds of horse and foot, who fired a succession of feux-de-joie on our approach, and made a great noise, shouting, fifing, and drumming, the horsemen manoeuvring parallel to our course, circling and firing. The men were clad in many colours, and the effect was good. Weather threatening, sky overcast, drops of rain occasionally, and distant thunder, all pronounced to be good omens. The mehtar is about 5 feet 9, and enormously broad, with a fist like a prize - fighter’s. Age perhaps seventy, large head,

aquiline features, complexion (the little of it seen above a red-dyed beard) pretty fair, hands very much so. A fine bearing and a determined cast of countenance. We rode hand-in-hand, according to a very disagreeable habit of the country, and, on passing his fort, were greeted by an artillery salute, most irregularly fired.

They found their camp pitched in a mulberry grove half a mile north of the fort:—

The weather was warm, and a shady camp was most grateful to all. From it the mehtaSs mud fort just showed through a mass of chinar and fruit-trees. Away to the east rose the huge snowy Torach-Mir (2 5,000 feet), like a mass of frosted silver in sunshine; at dawn receiving the sun’s rays whilst the valley was in profound darkness, thus presenting the phenomenon of “ a pillar of fire,” a mass of burnished copper, and passing as the sun rose through gold to the silver aspect it wore throughout day. There can be few more beautiful and striking sights than this in the world; and it is not surprising that the Torach-Mir should be the subject of fairy legend throughout the land.

On the 19th of September the officers of the mission with a small escort started to pay a visit to Kafiri-stan. After visiting the Durah Pass (14,800 feet), they crossed by the Zedek Pass (14,850 feet) into Kafiristan, and marched through the Bashgal country as far as Lut-Dih. For the first time Bashgal women and men were seen in their own country by a European. At two miles from Shui a deputation of Kaffirs—some fifty men and boys—met the party, with a very small pony, which Colonel Lockhart had to mount. The path ran through woods of birch and deodar on springy turf, and down the centre rushed a sparkling stream over granite boulders, widening and pursuing a more tranquil course over sand and pebbles as Shui was approached. The English officers marched in the midst of their strange hosts, “ who satisfied their curiosities as to the colour of their guests’ skin under their garments, the texture of their clothes, and the make of their boots, without any false modesty. The men and boys nearly all carried the national dagger, the hilt of carved steel and brass, and a short axe. In front of the procession went three musicians, playing on reed-pipes. A single reed was used by blowing across one end—as in pan-pipes—and the sound was modulated by several holes. The airs played were soft and melodious, different from anything before heard by the officers. There was nothing at all harsh or unpleasant in the music, the character of which was plaintive and melancholy.” The camp was pitched in the village, and in the evening the men came down to it and danced by a great log-fire : “It was a mixture of country-dance and Highland schottische. Advancing and retiring in lines, intermingling in couples, they kept excellent time to the music of reed-pipes and two small drums, and marked points in the dance by ear-piercing whistles on their fingers, and the brandishing of axes. The red firelight, the savage figures, and their fierce but perfectly timed gestures, presented a weird spectacle, which it would be difficult for an onlooker ever to forget.”

From Shui the party proceeded to Lut-Dih (6660 feet), which means “ The Great Village ” in the Chitral tongue. It contains 5000 inhabitants, and vines, apricot, mulberry, and walnut trees are abundant. After staying there a short time they returned to Chitral, from whence they proceeded back to Gilgit. Here they had to pass the winter, as all issues from the valley were closed by the snows. In April the mission again went forth to explore, and on the 9th of May they crossed the Wakhugrins Pass, whose crest they found to be 16,200 feet. On arriving at the plateau at the top, two miles broad, they discovered the ponies stuck—the snow was too soft. Some of their carriers, hardy mountain men, broke down and refused to go on, although their loads were taken from them. Two were stricken to death.

“ Every effort was made by the Sikh havildar and four men,” writes Lockhart, “who endeavoured to crawl with the dying men on their backs; but both legs and arms disappeared in the soft upper snow, and the exertion at 16,200 feet above sea was more than could be endured. The two creatures fainted continually, and, although I am pretty strong, I found that I was quite exhausted by mid-day from lifting an insensible man from the snow, reviving him, getting him on a few yards, and then having to lift him again.” Lockhart, the brave and generous soldier, carrying through the snow the dying coolie, makes a fine picture.

On the 26th day of August the mission returned to Kashmir, the officers having accomplished a most adventurous and interesting journey. They had succeeded in penetrating into Kafiristan farther than any European had ever gone, and had laid the foundation of our political influence beyond Gilgit.

“ The results of your mission,” wrote the Foreign Secretary to Lockhart, “ are of high value to the Government of India, and the Viceroy desires me first to inform you, as the responsible head of the undertaking, that he has noticed with much satisfaction the firmness, temper, and discretion which you have shown in circumstances of unusual difficulty and hardship.”

On his return from Chitral Lockhart was sent to command the Eastern Division in Upper Burma, and took a very prominent part in reducing the country to order. After the occupation of Mandalay and the nominal termination of the war, British authority hardly extended beyond the limits of our camps, and it was unsafe for an Englishman to move without a strong escort. Guerilla bands held the peaceable portion of the peasantry in terror. Here and there chiefs arose with sufficient influence to collect a force which amounted to a small army. These scattered bands had little communication with each other. But they moved quickly, and the character of the country, thickly covered with dense scrub jungle, and the sympathy and co-operation of the people, enabled them to elude pursuit. All who saw Sir William Lockhart’s work in 1886-87 bear witness to the able manner in which he conducted the campaign, and the untiring energy with which he followed the enemy. The thorough way in which Lockhart did the military work was a great help to the Chief Commissioner in establishing the civil administration. If there had been more Lockharts in command of brigades, the final pacification and settlement of the country would have taken less time to complete. For his services in Burma Lockhart received the degree of Knight Commander of the Bath. Then he enjoyed a brief period of rest as assistant military secretary for Indian affairs at army headquarters. But London as little suited the active soldier as Simla, and at the end of 1890 he gladly accepted the command of the Punjab Frontier Force. During his period of command he conducted four frontier expeditions. He was no believer in “ the policy of the bayonet and the firebrand,” but his aim was, by personal intercourse and neighbourly good offices, to “make mild a rugged people, and thro’ soft degrees subdue them to the useful and the good.” He, however, held that if an aggression had to be punished it should be done thoroughly. He harried Waziristan for months till he made the chiefs thoroughly understand the power of the British arm. He had a profound knowledge of the Pathan character, appreciated its good points, and had much sympathy for the Afghans, with their love of their Highlands, and admired their courage. When Sir Robert Sandeman died, Lockhart would probably have succeeded him as chief commissioner of Baluchistan if his services had been available. If a chief commissionership for the Trans-Indus territory had been created, Lockhart would, there is little doubt, have been appointed to the office. No man in India was so well suited to be the Warden of the Marches, and if he had been Warden no Tirah campaign would in all probability have been necessary.

Lockhart was on sick leave in England when the Afreedis sacked our forts and closed the Khyber. The frontier was in a flame, and he was hastily summoned to command the “ Tirah expeditionary force,” which had been gathered to punish the aggressors. The Afreedis are a large tribe, inhabiting the lower and easternmost spurs of the great Safed Koh or White Range, to the west and south of the Peshawar district. The area of the country inhabited by them is about 900 miles. The principal streams that drain these hills are the northern branch of the Bara river or Bara proper, the Bazar or Chuya river, and the Khyber stream, all flowing into the Peshawar valley. The valleys lying near the sources of the Bara river are included in the general name of Tirah, which comprises an area of 600 or 700 miles. By the camp-fires the Afreedi soldier loved to boast of the beauties and fertility of Tirah, and he used to state with swelling pride that it was a virgin land which had never been desecrated by the footsteps of a foreigner. Lockhart lifted the veil from Tirah, and its valleys were traversed by the British soldier. Lockhart had under him an army of 40,000 men, and he showed his military capacity by the way he handled them in a mountainous and almost impracticable country. It was the hardest bit of fighting we had done since the Crimea and the Mutiny. The storming of the heights of Dargai and the gallantry of the Gurkhas and Gordon Highlanders will be remembered as long as Englishmen reverence deeds of valour. The war did not strike the imagination of the British nation like the Soudan campaign. The skill and bravery displayed were not sufficiently appreciated, owing to newspaper correspondents sending home sensational accounts of insignificant untoward incidents which must occur in a war against a brave foe, armed with modern weapons, fighting in a difficult country of which he knows every inch. Sir William Lockhart told the present writer that the Tirah campaign had revealed to him that modern weapons had revolutionised the art of war. The methods practised on the parade would not answer against an enemy accustomed from childhood to carry arms, full of resources and wiles, fighting in their own land. “But what gave me the greatest satisfaction,” he added, “is the proof it afforded that the British soldier can fight as well as the British soldier fought in the Crimea or the Peninsula.”

After the war Lockhart was made a G.C.B. and appointed Commander-in-Chief in India. But the hand of death was on him. He struggled hard to perform the multifarious duties which the high and responsible office entailed, but illness again and again laid him low. Then came “one fight more, the best and the last,” and he fought it, as he fought all his fights, full of hope and courage.

On Sunday, the 20th of March 1900, William Lockhart died. He was a fine example of those virtues which a soldier should possess. He was brave, unselfish, and true, and the wild men of the frontier recognised the essentially chivalrous nobleness of his disposition.