|

Alma—Siege of Sevastopol—Inkerman—Private Prosser’s V.C.—The

Taku Forts—Changes of Organization and Title—Colours and Battle Honours—Bechuanaland.

There is no need to go into the series of diplomatic blunders

which led up to Great Britain, France, Turkey and (later) Sardinia being

ranged as allies against Russia. We have long enough recognized that our

support of Turkey was, in the late Lord Salisbury’s mordant phrase, “putting

our money on the wrong horse.”

The second battalion left Ireland for Cephalonia in the

Ionian Islands in January 1853, and remained in quarters there until April

1855. It was not until March 1854 that the first battalion sailed from

Plymouth to Gallipoli as a unit in Lord Raglan’s Crimean army, but it was

earlier in getting to work. Lt.-Colonel George Bell (afterwards Sir George

Bell, K.C.B., and Colonel of the regiment) was transferred from the second

battalion to take command and The Royals were in the first brigade of the

third division under Sir Richard England. On June 24 Varna was reached,

where the cholera scourge began to work, and the disembarkation on the soil

of the Crimea took place at Old Fort, Kalamite Bay, on September 14. Five

days later the army moved on Sevastopol and on September 20 was fought the

battle of the Alma. The Royals were in support and practically had no part

in the action. Colonel Bell makes no reference to them in his racy and

informing memoirs, Rough Notes by an Old Soldier.

On the 28th they took up their position on the heights above

Sevastopol and the siege began. The following extracts from Colonel Bell’s

diary give an idea of the winter’s work of the battalion—

“Oct. 10.

"By four in the morning, we had worked under cover, although

the ground was rocky, which gave us double trouble in carrying earth from

the rear to fill up the embankments. We stole away back to the camp

undiscovered before dawn, being relieved by another corps; and so I had the

honour of breaking the first ground before Sevastopol. I had supper about

twelve at night on the ground and in the dark—a bit of black bread, an

onion, some rum and water, and a headache.

“Oct. 17.

"The Russian batteries were firing lazily all night at random

—as much as to say, we are wide awake! 6.30 a.m., was the time appointed for

us to open the ball. Everyone was on the qui vive waiting the signal gun;

all had been in silence on our side during the night; exactly at half-past

six our signal-gun bid them good morning; the time had arrived to return all

civility for nineteen days of incessant cannonade. With right good will, and

an anxious desire to pay off old debts, a scene opened, such as never had

been witnessed since the invention of gunpowder; it was a battle of

artillery—some 2000 great guns opened their mouths of thunder, and iron hail

was showered from each side with the most determined and vindictive desire

to destroy life. The distance was 1,300 yards or thereabouts between us. All

our batteries opened at once; we saw the enemy at their guns, we saw every

fiery flash, and felt their metal; both parties soon got the range, and such

pounding and hissing of shot and shell, cutting through the air with that

velocity that bewilders one in his endeavour to protect his head when the

shot has really passed; flop, they come into the very bank you are leaning

against, and lodge there. A cross-fire now pours in upon us, ploughing along

our in-trenchments; we are enveloped in powder smoke; a breeze from the sea

clears all away; both antagonists in view of each other laying their guns to

the mark; shot coming and going like hail, and shells cracking death and

destruction wherever they explode. No delay beyond laying the guns and

loading. TTie sandbags fly out of their solid beds; the dust rises in clouds

at every volley, and breast-works topple over amongst the infantry. . . .

Look out!—a shot coming; see the flash, the word is hardly spoken, when it

is buried in the bank, or takes the crest of the cover above your head, or

meets a big stone, which turns its course; but they come so quick, ’tis

dangerous to move. Look out again, down, men!—a shell, it falls in the midst

of us and explodes. Oh 1 horrible; seven of my poor fellows—three killed,

and four wounded.

”The evening closes over a day on which some peaceful citizen

would say that hell had broken loose, with all the destructive powers of

darkness. Night comes at last. I shut up my note-book; all is quiet, but the

groans and the moans of the wounded, who are now sent up to camp; the dead

arc covered up; the quartermaster comes down in the darkness with his

barrels of ration rum, a welcome visitor. Pickets are posted, haversacks

opened, breakfast, dinner, and supper, on a bit of pork and onion, and a

biscuit, washed down with a little rum and muddy water; lie down in the

ditch, and asleep in five minutes.”

On November 5, the Russians made a violent surprise assault

on the British lines. It was the Battle of Inkerman. Some of The Royals

moved to support the threatened position : the rest were in the trenches.

Bell can tell the story—

”Before the dawn I was awoke by a heavy cannonade, which did

not disturb me in the least; but on the heels of this tumult came a

pattering of musketry, a sure indication of an attack; I jumped up and

looked out to listen; it was a raw, ugly, drizzling peep o’ day to cool our

courage and damp our powder. I heard the frenzied yell of the Russian

bloodhounds coming on with a quick and thickening fire, buckled on my sword,

and ordered the assembly to sound. What do we muster? '1374, rank and file,

sir; all the rest are in the trenches.’ I marched off to the right by order,

and took up position on the 4th Division ground, Sir George Cathcart having

gone forward to the right with his troops to share in the battle; advanced

across a ravine to the next hill, where we had a 68-pounder battery; it had

been taken by the enemy, and retaken; it was here that the brave Captain Sir

Thomas Troubridge lost both his feet by a cannon-shot, and there he lay in

patient anguish. The Russians made another effort to gain this battery, and

advanced on both flanks, and right up the breast of the hill; dividing my

force, I rushed down to the battery, and sent two companies into the two

ravines, one on each flank, to keep the enemy in check.

“Our position here was of the greatest importance; the enemy

made great efforts to get possession of our ground by turning our left; but

to lose our grasp would have been fatal, so we held on like grim death. It

is no easy matter beating the red devils on any ground, but to try it

up-hill was a forlorn hope; with all their powerful artillery, we crushed

their every effort. The Russians charged our troops with incredible fury and

determination. Ninety guns on the field were pouring death and destruction

into our ranks, firing our tents, and killing our horses; shells exploding

fast and furious. Fresh Russian columns were now advancing, before whom our

slender line gave way, rallied, charged, retired, and returned to the charge

against long odds. The rolling of the musketry continued, to the right,

centre, and left, as the enemy gained ground. They drove their bayonets

through our helpless wounded, who lay at their mercy, like dastard ruffians,

and beat in the heads of our officers while yet alive. One, in particular,

was frightfully abused. He was found on the field after the battle, and

lived on till next day in pain and sorrow. That was the gallant Colonel

Carpenter, who commanded the 41st Regiment. Our men got savage at this cruel

warfare; but yet, although they fell in scores at every volley, they seemed

to multiply. It became a hand-to-hand sanguinary struggle, marked by daring

deeds and desperate assaults; in glens and valleys, in brushwood glades, in

remote dells, the battle went on. At every corner fresh foes met our

exhausted troops, and renewed the struggle, until at length the battalions

of the Czar gave way before the men of England. It was a great and glorious

victory—as much as any victory can be gloriousI”

Bell was mentioned in the Inkerman dispatch and received the

C.B.

Disease proved far more deadly than the Russian fire, for in

five months it slew 321 men, while only seven were killed in the trenches.

The physical condition of those who survived may be judged from a note by

Captain Creagh, of the regiment, who took out a draft during the winter—

”Shortly afterwards, I also went on shore, and my first

impression justified a belief that prizes having been offered to the

dirtiest and most emaciated men and animals in the world, all those likely

to win it had come to Balaklava from every part of the earth.”

The second battalion arrived at Balaklava on April 28 and was

brigaded with the first. On June 18 an unsuccessful assault was made in

which a small party of the first was engaged, and on September 8, during the

last great bombardment of the doomed town, The First Royals took part in the

British assault on the Redan, which failed, while that of the French on the

Malakoff succeeded: the Russians evacuated Sevastopol next day. No more than

4 officers and 52 men of the regiment were killed in action during the whole

siege, and although the colours are inscribed Alma, Inkerman, and

Sevastopol, the Royals never had a real opportunity to show their full

mettle.

It was in this campaign, however, that the regiment secured

its only Victoria Cross during the nineteenth century. It was awarded to

Private Prosser for his distinguished conduct on the following occasions—

”On the 16th June, when on duty in the trenches before

Sevastopol, by pursuing and apprehending (while exposed to two cross-fires)

a soldier of the 88th Regiment in the act of deserting to the enemy.

”On the 11th August, 1855, before Sevastopol, by leaving the

most advanced trench, and carrying in a soldier of the 95th Regiment, who

lay severely wounded, and unable to move.

”This gallant and humane act was performed under a very heavy

fire from the enemy.”

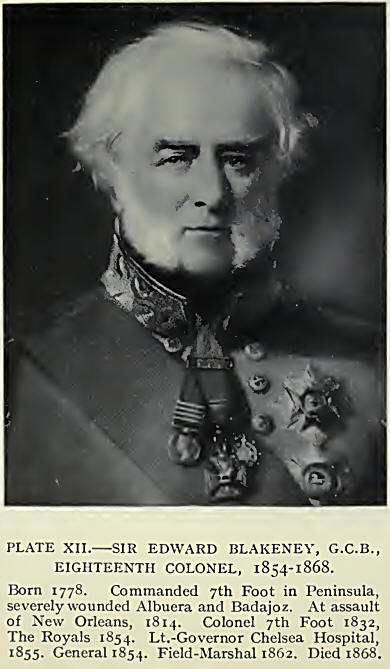

General Kempt had succeeded Sir George Murray as Colonel in

1846 and was followed by Sir Edward Blakeney in 1854.

After the Treaty of Peace was ratified in April 1856 the

first battalion returned to Aldershot and was reviewed by Queen Victoria. As

daughter of the Duke of Kent, an old Colonel of the Royals, she always

regarded herself as the daughter of the regiment.

In 1858 the time-honoured constitution of the regiment was

altered by the abolition of the Grenadier and Light Companies, and the

twelve companies of each battalion were made uniform.

In 1857 the first battalion went to India and the second

moved from Malta to Hong Kong in 1858. A detachment of the latter took part

in three expeditions into the interior of China, in which the French

co-operated. The Chinese “ Braves ” had been making trouble for the “foreign

devils” and it was necessary to punish them. Operations in January 1859

resulted in calming the country, but in the naval attack on the Taku forts

in June, Captain McKenna of The Royals, who was aboard the Chesapeake, was

mortally wounded.

Sir Hope Grant’s expedition to the North of China in May i860

was a more important movement. The Royals landed at Pehtang near the mouth

of the river Peiho on August 2, and helped to take the town. They were also

in the attack and capture of the Taku Forts on the 14th.

The next twenty years yield nothing of interest, but in 1881

the scheme of army reorganization abolished the old numbering of the

regiments, and instituted the system of linked battalions on a basis of

territorial titles, attaching to the reconstituted regiment the Militia and

Volunteer battalions of the district. This affected The Royal Scots much

less than the single battalion regiments, which were in

many cases grouped in pairs without any intelligent regard to

their previous history. The Royal Scots became ”The Lothian Regiment (Royal

Scots),” and at the same time they were clothed in trews of a tartan similar

to that worn by the Royal Highlanders. (This was altered in 1901 to the

Hunting Stewart tartan.)

In the following year, however, the title was changed again

to “The Royal Scots (Lothian Regiment).”

This is a convenient place to refer to the colours of the

regiment, because the oldest now in use by the regular battalions were

received from Queen Victoria in 1876, and are illustrated in Plate XIII. The

colours of the second battalion (Plate XIV) were presented by His Majesty,

King George V, as recently as 1911. The whole question of regimental colours

is full of interest. Captain H. M. McCance has set down everything there is

to be known about those used by The Royal Scots in an appendix to The

Records, and it is not possible to give here more than the briefest outline

of his researches. In the days when The Royals were a Scottish regiment

serving abroad for foreign monarchs, it is safe to assume that they bore on

their flag simply the white cross of St. Andrew. As the company was the

original unit in all military forces, so each carried its own colour as a

rallying point in battle. Dumbarton’s regiment must have looked gay enough

with its twenty-six companies, each headed by an ensign or standard-bearer

carrying the company colour. The first definite mention of the regimental

colours occurs in the journal of Dineley, who saw the lieutenant-colonel's

and major’s companies at Youghal in 1680. His drawing shows the white cross

of St. Andrew on a blue ground, the thistle and crown in gold surrounded by

the circle of St. Andrew, and the motto Nemo me impitne lacessit also in

gold. Drawings of 1693 exist, which show numerous flags captured by Louis

XIV, including three which The Royals lost at the battle of Landen. During

William Ill's reign the number of the colours borne by a battalion was

reduced from twenty-six to three, and in 1707 the Parliamentary Union of

England and Scotland destroyed the preeminently Scottish design of the

regimental colour. The earliest specimens which have survived date from

between 1775 and 1800, and are preserved at Gordon Castle by the Duke of

Richmond and Gordon, to whose family they doubtless came during or soon

after the colonelcy of Lord Adam Gordon. Next in date amongst the surviving

stands of colours are those of the third battalion, which served in the

Peninsular War and was disbanded in 1817. They are deposited in St. Giles’

Cathedral, Edinburgh, and are painted, not embroidered. Of about the same

date are the two stands of colours of the Edinburgh Militia, which have an

honoured resting-place at Dalkeith House. This regiment was the forerunner

of the existing Third (Special Reserve) battalion.

The colours of the fourth battalion were, if regimental

tradition is to be believed, sunk in the river Zoom, after the surrender at

Bergen-op-Zoom in 1814.

These must, however, have been recovered, for they now hang

in the Musee de l’Armee at Paris.

A very faded set of painted colours, which must have belonged

to the regiment between 1812 and 1825, hangs in the Royal Hospital,

Kilmainham. The first battalion’s embroidered colours of 1847 are preserved

in the Town Hall, Inverness, and those of the second battalion, 1847-67, in

St. Giles’ Cathedral, Edinburgh. At the same resting-place are the second

battalion’s colours used from 1867 to 1911. Captain McCance writes of the

present colours as follows—

“The regiment bears ‘the Royal Cypher within the Collar of

the Order of the Thistle, with the Badge appendant. In each of the four

comers the Thistle within the Circle and motto of the Order, ensigned with

the Imperial Crown.’ ‘ The Sphinx superscribed Egypt.’

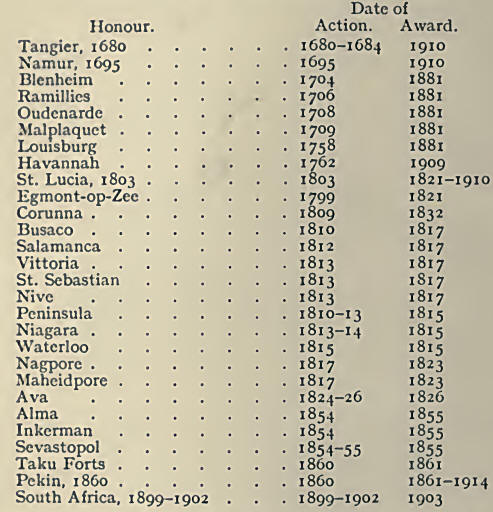

“ The following honours are also borne on the colours :—

"Note.—' St. Lucia’ was granted in 1821, and the date ' 1803

’ in 1910, to differentiate between the various dates on which the island

had been captured. The badge of a Sphinx, with * Egypt,’ was granted in 1802

to commemorate tnc Conquest of Egypt, 1801. Army Order, 208,of July, 1914,

granted the date i860, in addition to ' Pekin.’ ”

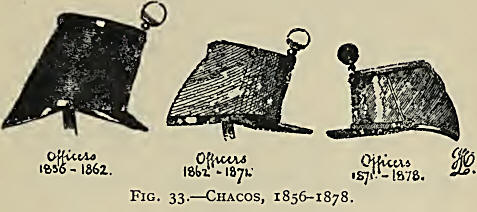

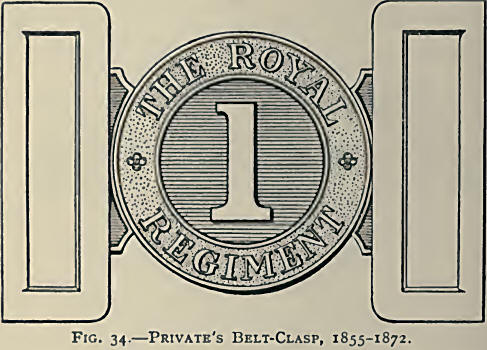

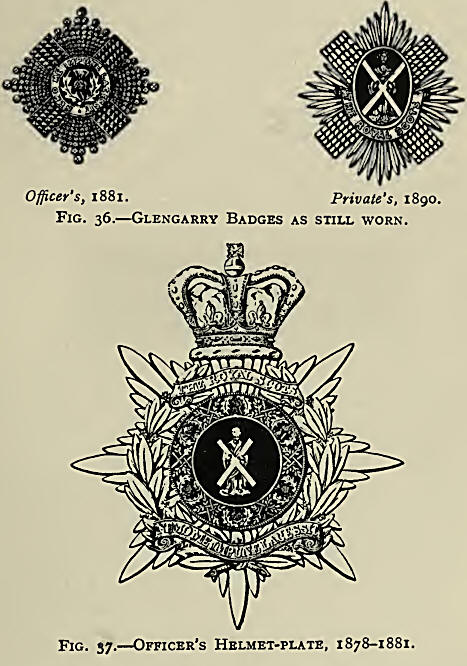

The clothing and equipment of the regiment was considerably

altered after the Crimean War. Chacos were found quite impracticable on

active service, and Kilmarnock forage-caps took their place. The old coatee

disappeared in 1855 in favour of a doublebreasted tunic, and officers’

epaulettes were given up in company with other decorative elements of

uniform. The chaco grew steadily shorter and uglier. Changes, more or less

trivial, were constantly made in cap-plates, belt-plates, etc., and the

various patterns, most of them discarded with as little apparent reason as

led to their adoption, repose peacefully in private collections of such

things.

In 1870 came a shattering announcement. Side-whiskers were

ordered to be abolished. The Glengarry superseded the Kilmarnock bonnet in

1874, and the diced border was added in 1880 in order to repair the lack of

national distinctions.

Chacos disappeared in 1878 in favour of the blue helmet, and

this gave the military tailors the chance to alter helmet-plates with

considerable frequency.

The introduction of the Territorial regimental system in 1881

led to many alterations, for the old time-honoured numbers were abolished.

The new doublet was ornamented with the thistle, still worn.

South Africa saw the regiment for the first time at the end

of 1884, when the first battalion arrived in December at Table Bay to serve

with the Bechuana-land Field Force under Sir Charles Warren. Some

filibustering Boers had refused to recognize the British Protectorate over

the Bechuanas, but the display of force was enough and no fighting took

place.

From then until the beginning of the South African War in

1899 there happened nothing worthy of special chronicle, except that General

Raymond, Colonel from 1877 to 1897, was succeeded by Major-General Sir E. A.

Stuart, Bart. |