|

Third Battalion at Quatre Bras—The attack on the Squares—

Waterloo—La Haye Sainte—The Royals and their Colours —The Fourth

Battalion—Bergen-op-Zoom.

On February 26 Napoleon left Elba, and reached France on

March 1. In three weeks he reinstated himself in power. Measures were

instantly concerted by the Allied Sovereigns to meet the danger. An army was

hastily assembled in the Netherlands, and placed under the command of

Field-Marshal the Duke of Wellington.

The third battalion embarked in May for Ostend with

Lieut.-Colonel Colin Campbell in command. On the night of June 15 it was at

Brussels, in Picton’s Fifth Division. When the alarm sounded, The Royals

fell in quickly and marched through the dark forest of Soignies. As they

were breakfasting there at eight o'clock, news came that the Allies were

hard pressed at Quatre Bras, and they left their meal unfinished and set out

again. No time was to be lost if the communications between the British and

the Prussians were to be saved. Twenty-one miles were covered by 3 p.m., a

great feat for hungry men marching in great heat through suffocating clouds

of dust. Arrived at Quatre Bras, the division lined up along the Namur-Nivelle

road. The light companies advanced against the French skirmishers and were

followed by the whole division (except the Ninety-second), suffering heavily

from musketry and heavy gunfire. Battalion squares were formed to resist the

fierce assaults of the French cavalry. The Forty-second and Forty-fourth

were surrounded in an especially exposed position: Picton led The

Royals1 and the Twenty-eighth in quarter column through the French troops

and ordered them to form a square.

The repeated and furious charges which ensued were invariably

repulsed by The Royals and the 28th, with the utmost steadiness and

consummate bravery, and although the Lancers individually dashed forward and

frequently wounded the men in the ranks, yet all endeavours to effect an

opening of which the succeeding squadron of attack might take advantage,

completely failed. The ground on which the square stood was such that the

surrounding remarkably tall rye concealed it in a great measure in the first

attacks, from the view of the French cavalry until the latter came quite

close upon it, but to remedy this inconvenience, and to preserve the impetus

of their charge, the Lancers had frequently to recourse to sending forward a

daring individual to plant a lance in the earth at a very short distance

from the bayonets, and then they charged upon the lance flag as a mark of

direction.

Despite shortness of ammunition The Royals never flinched.

Charged again and again by an infinite superiority of numbers, they never

gave way to the French cavalry. An eyewitness, who had been with the

regiment all through the Peninsula from Busaco to Bayonne, wrote that they

had never shown a more determined bravery—

Along the whole front of the central portion of the

Anglo-Allied army, the French cavalry was expending its force in repeated

but unavailing charges against the indomitable squares. The gallant, the

brilliant, the heroic manner in which the remnants of Kempt’s and Pack’s

Brigades held their ground, of which they surrendered not a single inch

throughout the terrific struggle of that day, must ever stand prominent in

the records of the triumphs and prowess of the British infantry.

When darkness fell the French retreated to the heights of

Frasnes, and The Royals were left on the field with 26 dead and 192 wrounded.

A renewal of the attack was expected in the morning, but the

French made none, and the division was moved back to high ground in front of

the village of Waterloo, and reached the new position as the sun went down.

The troops passed a miserable night, for rain fell in torrents, and a

thunderstorm burst over them. It was therefore a wet, weary, and half fed

regiment that woke to the morning of Waterloo.

The Fifth Division was in the British centre, and The Royals,

now again brigaded under Pack and much reduced in numbers, were commanded by

Major Robert Macdonald.

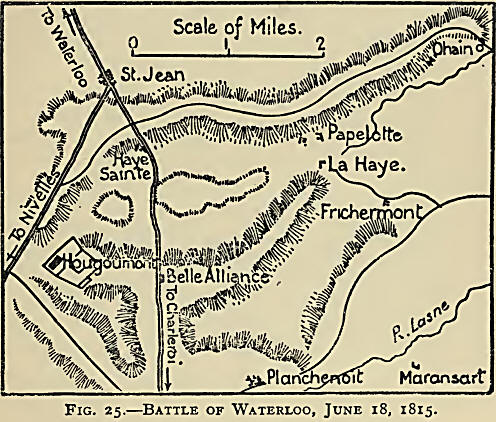

They stood on the north side of the Ohain road a little

north-east of La Haye Sainte, and facing south. After pounding them for two

hours with artillery, the Emperor sent 13,000 foot against Picton’s 3000.

The attack was repulsed by crashing volleys, and by a counter-charge w’hich

left many French prisoners in British hands. The cannonade began again, and

Pack's brigade had to withdraw to its original position behind a sheltering

ridge. Later in the afternoon the French captured the farm of La Haye Sainte

and the brigade was searched cruelly by the enemy's riflemen, but the

squares held their ground immovably and the French never crossed the Ohain

road. The crisis of the battle took place in another part of the field, and,

before the last effort of Napoleon's Old Guard, the firing from La Haye

Sainte had become feebler and feebler until it ceased. About eight o'clock

in the evening The Royals broke southwards across the road, and the long

disputed farm was taken. On this day they lost less heavily than at Quatre

Bras, 15 killed and 128 wounded, but on the two days their original strength

of 624 was reduced by 363. Four officers and the sergeant-major in turn fell

as they were carrying the King's colour. Amongst them was Ensign Kennedy. He

was carrying a colour in advance of the battalion and was shot in the arm:

he continued to advance, and was again shot, but this time killed or

mortally wounded. A sergeant then attempted to take the colour from him but

could not disengage his grip. He then threw the body over his shoulder and

rejoined the ranks of his battalion, through the chivalrous action of the

officer commanding the French battalion opposed to the Royals, who ordered

his men not to fire on the sergeant and his burden.

In such fashion did The Royal Scots make history at Waterloo.

The battalion marched into France with the army of

occupation, and after Napoleon’s flight “Waterloo” was added to the colours.

The return home was delayed until March 24, 1817, and the third battalion

was disbanded a month later, after fifteen years of glorious life. The men

who were not due for their discharge were transferred to the first and

second battalions.

The Fourth Battalion

We must now return to the other service battalion, the

fourth, raised at the same time. It was used mainly as a depot battalion for

providing the other three with drafts, and was recruited much from the

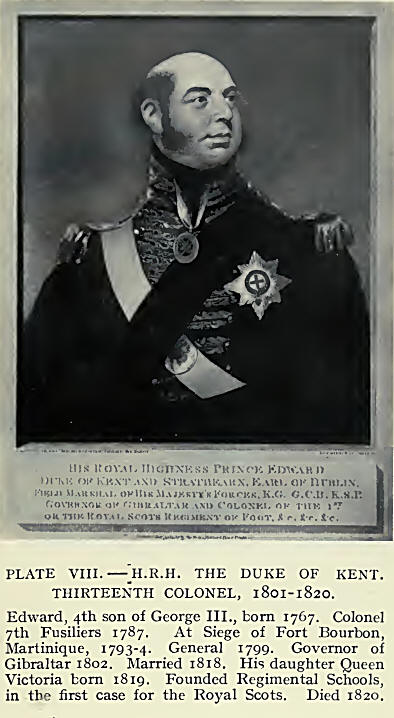

Militia. It is worth noting that about this time The Royals, alw'ays

pioneers in military reform, wfere the first to establish a regimental

school, at the instance of their colonel, The Duke of Kent. Its teachers

were often borrowed by other regiments, and its services to the general

cause of education were real and valuable.

It was not until 1813 that the fourth saw active service as a

separate unit.

The invasion of Russia by Napoleon, the burning of Moscow,

the disastrous retreat of the French army from the North, and the separation

of Prussia, Austria and other states from the interest of Napoleon, were

followed by a treaty of alliance and subsidy between Great Britain and

Sweden, in which it was stipulated that a Swedish army, commanded by the

Crown Prince, should join the Allies. On August 2 the battalion embarked,

under the command of Lieut.-Colonel Muller, for Stralsund, in Swedish

Pomerania, forming part of an expedition under the orders of Major-General

Gibbs. Thus The Royal Scots went to the same part of the world to which a

body of their daring countrymen, who formed the nucleus of this

distinguished regiment, proceeded exactly two hundred years before to engage

in the service of the Swedish monarch.

On Christmas Eve they were moved to Lubeck to support the

army of the Crown Prince of Sweden.

In the meantime, the Dutch were making an energetic struggle

to free themselves from the power of Napoleon, and a strong party had

declared in favour of the Prince of Orange. A British force was sent to the

Netherlands, under the orders of Sir Thomas Graham, and the fourth battalion

of The Royals was ordered to join the troops in Holland. It began its march

from Lubeck on January 17, 1814, and encountered many difficulties. While

crossing the forest of Shrieverdinghen, 120 men were lost in a snowstorm;

much suffering occurred during the journey, and on March 2 the men went into

cantonments at Rozendahl. The battalion was then ordered to join the force

destined to make an attempt on the strong fortress of Bergen-op-Zoom.

The attack was made on the night of March 8. The Royals

crossed the Zoom and forced an entrance by the water-port. Having gained

possession of the ramparts round the water-port gate, the battalion was

exposed to a heavy fire of grape and musketry from two howitzers and a

strong detachment of French marines. Two companies were detached to keep the

enemy in check, and were relieved every two hours by two other companies of

the battalion. They were thus engaged from eleven o'clock until daylight,

when the enemy made a furious attack in strong columns, which bore down all

before them. The two detached companies of The Royal Scots were attacked by

a host of combatants and driven in. A heavy fire of grape was opened upon

the battalion from the guns of the arsenal, and it was forced to retire by

the water-port gate, when a detached battery opened upon it. Being thus

placed between two fires, with a high palisade on one side and the Zoom

filled with the tide on the other, the battalion could do no more. The

colours were first sunk1 in the river Zoom by Lieutenant and Adjutant

Galbraith; the battalion then surrendered on condition that the officers and

men should not serve against the French until exchanged. The failure of the

coup-de-main on Bergen-op-Zoom occasioned an immense sacrifice of gallant

men. Forty-one were killed, 75 wounded, and 593 taken captive, but the

prisoners were allowed to return to England on April 8, and a month later

the battalion sailed for Canada, whence it returned in January 1816 and was

disbanded. |