|

IF the Great War has reversed

some preconceptions and ruthlessly rationalised many traditions, it has

confirmed, and actually enhanced, the fine fighting reputation of the

ten Regiments of the Line—half of them kilted— which Scotland

contributes to the British Army. We now know of a certainty that this

reputation is well founded as we did not know it before. True, there has

long been a legend to that effect, but of recent years there has been a

disposition to question its validity. Scotland, or rather the articulate

part of it, has borrowed the deadly doctrine of self-depreciation, from

which the dominant partner has suffered severely, and the suggestion has

not been wanting that the praise of Scots troops, which received such an

impetus from the enthusiastic pen of the author of Time Romance of War,

was somewhat overdone. We were reminded that our Army had not had to

face troops on the Continent of Europe since the days of the Crimea one

Scots Regiment had not done so since 1799, while the Gordons had nothing

to show for it since Waterloo.

If that was true of the old "Contemptibles"

generally, it was still truer of the auxiliary forces, which had seen no

fighting at all, except in South Africa; but to-day all of them have

stood the acid test of the greatest war in history. The old "Contemptibles"

were never finer, and we have lived to see one of the best Divisions in

the Army composed entirely of kilted Territorials. Indeed, a cloud of

witnesses has arisen to prove that all the 126 Battalions, into which

the 69 composing the Scots Regiments expanded themselves for the

purposes of war, have rendered magnificent service. If we relied merely

on the word of the Commander-in-Chief we might suspect bias, for Earl

Haig and more than one of his Generals are Scots by birth but we have

the appreciation of the special newspaper war-correspondents, and not

one of them hailed from north of the Border.

We have, moreover, the testimony of the enemy, who

very quickly recognised the valour and skill of all the Scots Regiments,

particularly those of the 51st Division. Indeed, the Scots soldier,

although lie represented only eleven per cent. of the British Army

against eighty-one per cent, of England itself, took hold of the

imagination of the Germans to such an extent that their caricaturists

turned John Bull into a Highlander, converting his traditional tall hat

into a diced "cockit" bonnet, his white riding breeches into a kilt or

tartan trews, and his top-boots into gaiters. The pages of

Simplicissmu.s, Klaclderadaisch, and Jugend, to name only a few, have

throughout the war pictured a long procession of the "wife-men" as

representing the British Army, at first in a spirit of incredulous

burlesque, and latterly with something of the wholesome fear, which was

popularly supposed to have overtaken George the Second when he started

in his sleep in terror as he dreamed that the "Great Glen-bogged" (Glenbucket)

was swooping down upon him.

It was to the advent of the father of that monarch

that we owe the raising of the kilted Scots—nearly all the trewsed

Regiments arose in the previous century—though the connection was

indirect, not to say inverted, and was touched with an irony (especially

in the light of the greatest of wars), which has been largely lost on a

certain type of popularly accepted English history. According to this

reasoning, the Highlanders, on seeing the country in danger owing to the

expansion adventures of the dominant partner at the expense of France,

flocked to the colours at the call of the English Government, and thus

not only helped to save the Empire, but gratified their own passion for

arms, which had been severely suppressed after the Forty-Five.

The facts, however, are very different from this

facile theory. To begin with, if the country as a whole had little

consciousness of expansion, as Seeley argued, the Highlander had

infinitely less, for one of the main troubles of dealing with him, even

in our own day, has been his homing instinct, his intense love of his

native soil, no matter how poor it may be. In the second place, the

ambitions of the House of Hanover touched no responsive chord in the

Highlander's heart, for the Clans had felt the full scourge of Teutonism

in the ruthless work of Cumberland at Culloden.

Again, if France was the hereditary arch-enemy of

the dominant partner, Scotland in general and the Highlands in

particular, had no such quarrel with her. On the contrary, France and

Scotland, linked together by racial, psychological, and historical

similarities and identities of interest, had long been the best of

friends, and it must have puzzled the average Highlander why he should

be asked to fight against her. So strong is this community of spirit

that it might very well be argued that the Highland Regiments have never

fought better in their long history than they have done in the Great

War, because they were fighting for France, as well as for their native

country.

No doubt the

Union had placed Scotland in the same category as England so far as

France was concerned, but the kilted regiments arose, not so much out of

a political necessity as from a revival of the spirit which had made the

Scot in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries a soldier of fortune

wherever he was wanted, fighting now for Rome, and now in the ranks of

Gustavus Adolphus against her; fighting to a large extent without

passion, but as an artist in arms; and it was this absence of bias as

much as anything else that made these venturers clean fighters, and

raised their reputation as masters of their art wherever they took

service.

From first to

last the spirit which animated the soldier of fortune—out to gratify his

instinct for adventure, his desire to make a living, and his passion for

individuality—has always inspired the Highland regiments to a remarkable

extent. It is true that the war with France involved the most momentous

issues for the State, but the methods adopted for warding off the danger

were far more personal and local than national. It might be argued that

the real cause of the war with France was due to the imperialistic

ambitions of individual adventurers, and therefore raised little

national animus, but precisely the same methods of meeting a crisis

coloured the early stages of Armageddon, when every one felt involved,

the influence of one man, Lord Kitchener, being far more potent in

rousing resistance than any abstract doctrine of State necessity.

The raising of troops to fight France was at no

time the complete State undertaking that conscription has involved in

our own day. At first the duty was taken up by individual landowners,

who raised in turn Regiments of the Line and Fencible Corps; and when

their pockets were exhausted, the task was assigned to local authorities

like the Lords Lieutenant, who were commissioned to raise in turn

Militia, Volunteers (1794-1808), and the very curious force known as

Local Militia (1808-1816).

Scotland afforded a splendid ground for the

exercise of personal influence because, although the Clan system with

its chieftainship had broken down, the influence of the great landowners

was still powerful enough to attract attention, although the devotion of

the people had to be reinforced by bounties on a scale unknown in our

day, and by all sorts of practical recognition, such as the adjustment

of rents and the enlargement of holdings for, although the armies thus

raised had strong affinities with the levies organised under the feudal

system, the Clan system was infinitely more democratic, and gave scope

for greater individuality. This is so true that it often happened that

the men raised in one glen declined to march to the rendezvous with the

men of another glen who happened to be their hereditary enemies, and

trouble arose over the demands of particular groups to be led by their

local officers, some of them even believing that they should go forth to

battle by Clans, as in the old days.

Of all the personal potentates interested in

recruiting in Scotland, none was more powerful than the fourth Duke of

Gordon who, although long in possession of vast tracts of Highland

territory, was in no sense a Highlander, his family having migrated from

Berwickshire to the north, and the trouble which existed for centuries

between him and his Highland tenants, like the Macphersons, was due to

the inability of his ancestors, or their representatives, to understand

the true nature of the Celt. More motives than one urged His Grace

forward as recruiter. In the first place, his immediate ancestors had

played a very dubious part in the Jacobite risings, and the fourth Duke

was anxious to remove the last doubts as to the loyalty of his house.

Later on he married an extremely clever and ambitious woman, the famous

Jane Maxwell, who had a great desire to play a big part in the State,

and do something for her sons.

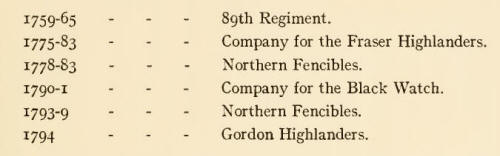

Whatever the motives, the recruiting achievements

of His Grace were splendid, for from first to last lie raised no fewer

than four complete regiments, besides contributing two companies to

corps raised by others. and he also played a very active part as Lord

Lieutenant of his county, The forces organised by the Duke were as

follows:

The sole remnant of this mighty effort, which must

have cost the Duke a fortune, is the regiment of Gordon Highlanders,

which we have seen blossom out into eleven battalions, to say nothing of

certain reserves; and although the regiment has not continued to be

recruited on the ducal estates, its connection with the House of Gordon

has all along been maintained, and has actually been strengthened in

recent times. That connection of course has always been symbolised by

the wearing of the clan tartan, but the links with the north were

strengthened by the rearrangement of 1872, when infantry regiments were

allotted to definite Territorial areas for the purpose of recruiting.

About the same time the Gordon family motto, "Bydand," and the familiar

crest were placed upon the bonnet in lieu of the hard-won Sphinx.

What is of much more importance is the fact that

the genius of the family, admirably described in the alliterative phrase

the "Gay Gordons," which inspired the original regiment, has passed into

all its subsequent accretions, so that the 75th Regiment added to it in

1881, although actually of earlier origin, has been completely absorbed.

The same can be said of the old Aberdeenshire Militia, which became the

3rd Battalion, and also of the various Volunteer Corps which were

gradually absorbed, while the Service Battalions raised by Lord

Kitchener displayed exactly the same spirit as the cradle corps. This

continuity and identity of tradition are also emphasised, not only in

the Gordons, but in all the Scots regiments, and especially in the

kilted units, by the fact that they alone maintained during the War at

least, part of their Peace equipment in the shape of the kilt—even if it

was camouflaged with khaki aprons—and the trewsed regiments had their

glengarries replaced by Kilmarnock and other braid bonnets.

Who can doubt that such a continuity of outward

traditions is but the symbol of a spiritual identity which links up the

Scots regiments of the present day with the Corps who did such splendid

work of old from Fontenoy to Waterloo, from the Crimea to South Africa.

True, when you come to define it, it is difficult to say what it

precisely consists in. Nearly every Regiment of the Line has its own

peculiarities, but the Scots regiments have them in even greater

abundance, for with them they are reinforced by marked racial

characteristics. It is perfectly true that the Highland regiments are no

longer confined to Highlanders, or even to Scotsmen, although the idea

industriously propagated some years ago that they were originally

composed largely of Irishmen, is a fallacy, completely disproved by War

Office Records. Even if it were otherwise, the fact remains that the

esprit de corps which all these idiosyncracies help to form has a

remarkably proselytising influence, very subtle and difficult to define,

but very potent in actual practice.

The early history of the Gordons is full of

curious little incidents which sometimes run counter to popular notions.

For example, it used to be commonly only supposed, especially in support

of the now exploded theory that we have become "degenerate," that the

first recruits of the Highland regiments were gigantic men. This is far

from being the case. From the Description Book of the Gordons, one of

the very few regiments which possess such data in an early form, it is

proved that the average height Of 914 men composing the greater part

(940) of time original regiment, was only 5' 5½", only six of them being

6' or upwards—the tallest, a 'Morayshire man, scaling 6 4'. Similar

facts can be cited about the heights of other groups of men at the same

period.

There were only 16

men actually named Gordon, against 39 Macdonalds, 35 Macphersons, and 34

Camerons. As to the occupations of the men, it is interesting to note

that 442 were described as "labourers," and as most of them came from

the Highlands, they were presumably farm servants. Of skilled artisans,

186 were weavers. Inverness-shire, where the Duke had vast estates,

supplied 240 men, Aberdeenshire 124, Banffshire 82, Lanark 62, Ireland

51, England 9, and Wales 2.

There was a solitary German in the regiment, a

musician named C. Augustus Sochling, hailing from Hesse Cassel. There

was another German in the regiment later on, also a musician, named

Friederich Zeigher (or Zugner) who fell at Quatre Bras. The appearance

of these Germans was in its way a sort of return for the fact that the

House of Gordon had given many good soldiers of its name to what we now

call Germany, although most of them really took post in Poland. The

descendants of at least four of these soldiers still exist in Germany,

and have risen to the dignity of a \fl including the founder of the von

Gordon-Coldwells, of Laskowitz, in West Prussia, the von Gordons of

Frankfurt, and the family of Dr. Adolf von Gordon, the well-known Berlin

lawyer, whose motto is "Byid Dand." Although at the beginning of 1914 he

told a Berlin newspaper that he knew nothing more about it than that it

was an " altschottischer Spruchi,"it is, of course, nothing more or less

than the historic word " Bydand."

With regard to the pipe history of the regiment

not very much is known. I fancy this is due to the fact that so much

that has to do with the art of piping generally rests on oral and not

written tradition. In the second place it must be remembered that pipers

were not originally recognised by the State. They were purely a

regimental, and not an Army, institution, and had no separate rank as

the drummers had. Indeed, it was not till about 1853 that they got the

same rank and pay as drummers. Thus, in May 180, a piper named Alexander

Cameron was taken on the strength of the Grenadiers as drummer, probably

to get him drummer's pay, to which, as a piper, he was not entitled.

The rivalry of the two is

brought out in a story told in Carrs Caledonian Sketches, of a dispute

as to precedence between a piper and a drummer of a Highland regiment.

When the Captain decided in favour of the latter, the piper expostulated

with the remark, "Oh, sir, shall a little rascal that beats a sheepskin

take the right hand of me that am a musician?" The differentiation of

the two is still reflected in the fact that a piper is always a piper,

whereas a "musician" returns to the ranks in time of war.

The first direct mention of pipers in the Gordons

occurs in a regimental order of October 27, 1796, when the regiment was

at Gibraltar, and when it was ordained that pipers were to attend all

fatigue parties. An interesting sidelight on the use of the pipes occurs

in a regimental order of November 12, 1812, when the regiment was at

Alba de Tormes in Spain:

"'l'he pibroch will never sound except when it is for the whole regiment

to get under arms; when any portion of the regiment is ordered for duty

and a pipe to sound, the first pipe will be the warning, and the second

pipe for them to fall in. The pibroch only will, and is to be

considered, as invariably when sounded, for every persons off duty to

turn out without a moment's delay."

A pathetic little story about this function of the

pipers is told by James Hope in his forgotten little book, Letters from

Portugal, Spain and France, printed in 1819:

"At ten o'clock (on the evening of the day of

Quatre Bras) the piper of the 92nd took post under the garden hedge in

front of the village, and, tuning his bagpipes, attempted to collect the

sad remains of his regiment. Long and loud blew Cameron, and, although

the hills and vallies (sic) reechoed the hoarse murmurs of his favourite

instrument, his utmost efforts could not produce more than half of those

whoin his music had cheered in the morning on their march to the field

of battle."

At the battle

of St. Pierre in the Peninsular, December 13, 1813, two out of the three

pipers of the Gordons were killed while playing the pibroch "Cogadh na

sitli " (with which they were to charm the ears of the Czar of Russia in

the great Review at Paris in July, 1815). As one fell, another took up

the tune, and it was suggested to Sir John Sinclair, as President of the

Highland Society, that this "should be made known all over the

Highlands." It may be noted that the Colonel, the gallant, if martinet,

Cameron of Fassiefern, who fell at Quatre Bras, gave great encouragement

to his pipers, especially as regards the specially Highland airs and the

high-class music (Ceol Mor). Colonel Greenhill Gardyne attributes to

this the fact that "all pipers in the Gordons are still taught to play "Piobaircachd,"

and that the ancient and characteristically Highland class of pipe music

is still played every day under the windows of the officers quarters

before dinner.

The Gordons

have enjoyed the services of one particular family of hereditary

ear-pipers, the Stewarts. They came from Perthshire, where one of thein.

was a piper to the Duke of Atholl, while his brother, known as "Piper

Jamie," crossed time hills into the Parish of Kirkmichael, Banffshire

—the cradle of a remarkable military family, the Gordons of

Croughlywhere seven sons were born to him. All of these strapping

fellows entered the Aberdeenshire Militia, now the 3rd Battalion of the

Gordon Highlanders, six of them becoming pipers. The best known of these

was the eldest, Donald (1849-1913), who migrated to New Deer,

Aberdeenshire, and was known all over Scotland as a champion piper. The

family has been supplying pipers to the Gordons for more than half a

century.

No doubt modern

battles are not won by deeds of individual daring such as these pipers

have achieved, but they are won in terms of the spirit which makes such

conduct possible, for it is just the little things, the train of

tradition, the idiosyncracies of uniform, and the rest of it, which go

to form that esprit de corps which has made time kilted regiments famous

the world over.

|