|

IT is related by Sir John Graham

Dalycli how in 1818, one John Campbell from Nether Iorn, brought "a

folio in MS., said to contain numerous compositions," for the inspection

of the judges at the annual piping competition held in Edinburgh under

the auspices of the Highland Society the story goes on, "but the

contents merely resembling a written narrative in an unknown language,

nor bearing any resemblance to Gaelic, they proved utterly

unintelligible. Amidst many conjectures relative both to the subject and

the language, nobody adventured so far as to guess at either airs or

pibrochs." It is believed that this is the earliest authentic reference

to the pipers notation known as Canntaireachd, and it is of interest to

note that even as early as 1818, among the class of Highland gentlemen

who acted as judges at the biggest competition in the country, the very

existence of the notation was unknown. Sir John mentions also that he

made later attempts to acquire this MS. volume and to trace two others

in the possession of John Campbell's father : his attempts were

unsuccessful.

In 1828

Captain Macleod of Gesto published some pipe tunes in Canntaireachd as

taught by the MacCrimmons in Skye. The merits of this publication have

been made the subject of controversy among pipers and others; this

controversy has no place in this paper. The late John Campbell (lain

Ileach) of Tales of the West Highlands, wrote a monograph on

Canntaireachd in 1880, in which he reviewed Gesto's book: the monograph,

interesting as it is and written in lain Ileach's easy flowing style is

extraordinarily disappointing. In spite of his comprehensive knowledge

of folk-lore--more particularly of Gaelic folk-lore--he fails to

indicate any probable source of this notation—probably no one in Europe

was, or is better fitted to make conjectures on the point. However, he

made two statements of interest in the late history of the notation, (1)

that he had often seen my nurse John Piper reading and practising music

from an old paper manuscript, and silently fingering tunes. I have tried

to recover this writing, but hitherto in vain, and (2) that there were

three local varieties of the notation (a) MacCrimmon (b) MacArthur, and

(c) Campbell of Nether Lorn. Now "John Piper" was this same John

Campbell of the family of Nether Lorn, which possessed three MS. volumes

of Canntaireachd.

Among

the older-fashioned pipers in Scotland, even just before the war, one

constantly heard syllables (hodroho, hiodro, etc., etc.) being used,

generally at haphazard, seldom in their correct place. The astounding

thing is that even fragments of a notation, the system of which had been

out of use for so long, should have survived to this day.

About 1912 two of the Nether Lorn MS. books were

rediscovered, and from them it has not been hard to reconstruct the

system of notation. Those tunes with recognisably the same names as we

know them by to-day, furnished the first step in the problem : after

that it became easy to identify other tunes with different names, and

finally to rediscover a number of tunes which have been lost for an

undetermined period.

One

word of caution will be necessary to certain pipers before going further

into this subject. This notation, invented for and suitable only to

piobaireachd, is not going to teach pipers how to play piobaireachd.

There is and always has been, one way and only one way to do that—to get

instruction from a master once that is accomplished, a pupil may be fit

to learn more tunes by himself from books written in any intelligible

notation. This I take to be true of any musicians and any music.

The piobaireachd pupil might well get his

instruction through the medium of canntaireachd, for it has been made

solely for this music, and is in point of fact very suitable for the

purpose. To begin with, if the few master- instructors of piobaireachd

will take the trouble (and assuredly it will not be great to them) to

become familiar with canntaireachd, and to use it as a medium of

instruction, it is a matter of certainty that they will realise its use

for this end—for instead of a perplexing maze of notes and grace-notes

in staff notation to correspond to any movement which they are trying to

teach their pupil, they will have pronounceable vocables which will act

as memoria technica to the pupil : the pupil will, at first, learn these

parrot style, until he gets to a certain length, when, unaided, he will

begin to see that these vocables he has learnt convey a definite

meaning—a definite combination of note and grace note, in a fonit which

can be crooned to the air. I have found that for the purposes of

learning new tunes, staff notation compared with canntaireachd is

cumbrous and misleading: and even when written in an abbreviated form

(as in General Thomason's great book, Ceo! Mor) it appeals mainly to the

eye, while canntaireachd appeals to the ear.

For some years now I have found it invaluable as a

kind of musical shorthand, and with a certain amount of practice it

becomes possible to write down a time in canntaireachd while it is being

played, and then to learn it at leisure. 1 had the triumph of converting

a brother piper a few years ago. He was inclined to be sceptical about

the whole system, so to test me and it lie played me a tune which I had

never heard and I wrote it down as he played it. After he had finished

he said, Now we shall see what is in it, for I made two mistakes: play

what you have got and Ave shall see." I played on the practice chanter

just what I had written, with the mistakes, of course, included.

Again, when one is judging piobaireachd

competitions, it is valuable as shorthand to jot down notes of mistakes,

etc.

Before coming to the

notation itself, it should be explained that it is not maintained for a

moment that this variety (the Nether Lorn) is superior in any way to the

MacCrimmon or MacArthur varieties. It is merely given and suggested for

use, because it is this variety which has become once more available to

pipers at large. There are people who undoubtedly call the same for the

MacCrimmon variety also, and it is sincerely hoped that they will do so.

That all three varieties are first cousins to each other is beyond doubt

to any one who compares them perhaps at a later date, when more

knowledge of canntaireachd becomes available, it may be possible to

point to one as the original, or to find a common ancestor to all.

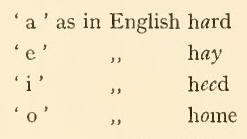

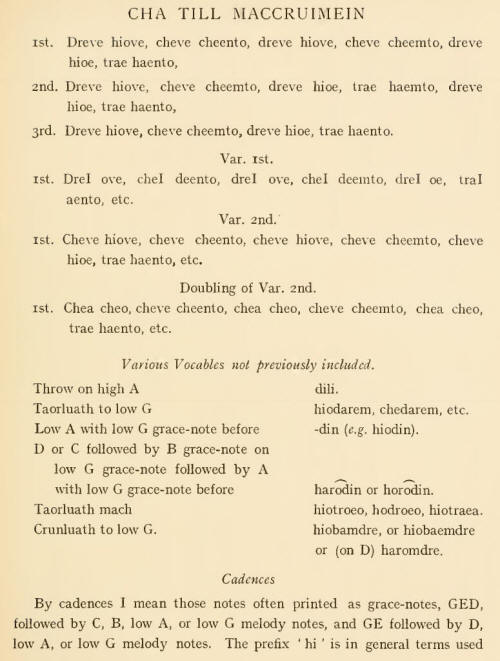

Coming now to the actual notation, the following

paragraphs should be read, subject to this note that the pronunciation

of the vocables must he largely a matter of conjecture, but it is

reasonable to suppose that, as they were written in the manuscript and

used by Gaelic-speaking pipers,' the pronunciation should have at least

some reference to Gaelic pronunciation —thus the vowels, when occurring

as the last letter of the syllable, would be pronounced

and

probably the consonants should be given their Gaelic equivalents also

(all which can best be obtained verbally from a Gaelic speaker).

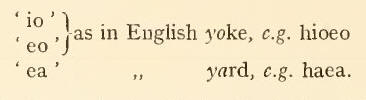

In addition to the simple vowels, combinations

occur which require to be sounded as diphthongs:

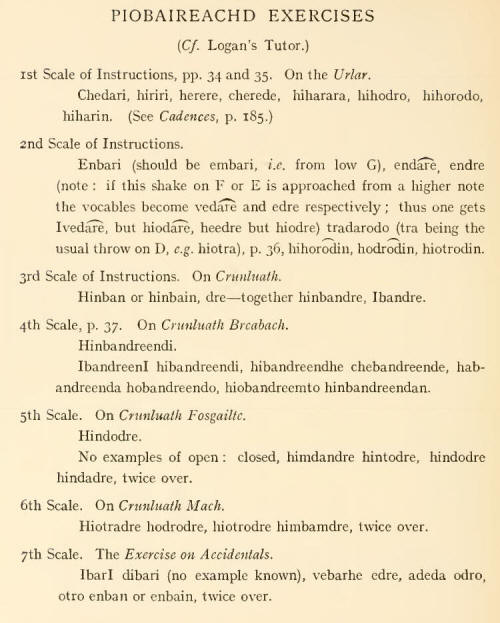

for this, e.g. hiharin, hihorodin. Taking them in

above order, examples of the vocables used are, of the former, iiihodin,

hihioern, hihinbain, and hiharnbarn, and of the latter hiaen, hienem,

hiemto. It is one of the remarkable points in the MS. that these

cadences are indicated to a far less extent than is played by

traditional players of modern times, and I am as yet unable to make any

deductions from the manner in which they appear as to the style in which

the MS. intends them to be played. To avoid confusion between ' hi ' as

cadence and high G with A grace-note, it would be better to use the

alternative ' chi' for the latter.

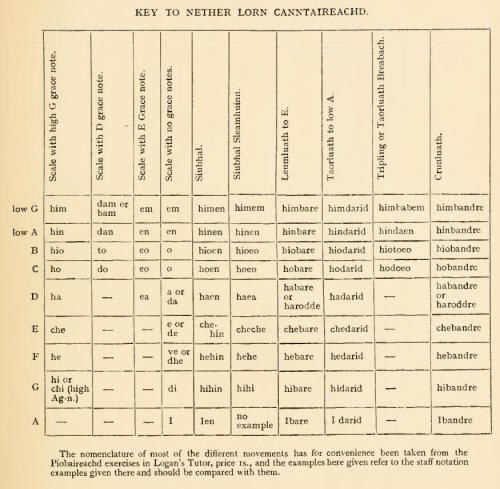

General

A study of the key will reveal various noticeable

points, some of which I will touch on here. It will be seen that some of

the composite vocables can be pulled to pieces into their component

parts, e.g., hiotroeo, hinbandre, etc., while others can only be

dissected to a lesser extent, e.g., hindaen in the Tripling or Taorluath

Breabach ; in this latter case the vocable must be read in its context,

for hindaento might be 6 low A, D, low A, B, while standing by itself,

but in conjunction with a string of others it is undoubtedly meant to be

the Taorluath Breabach. Again there is liable to be confusion between

'en 'low A without any and with an E grace-note, and in some few cases

it is impossible to say definitely which is meant omi the other hand it

is used in the siubhal variation, and there can be no doubt in such a

context hinen by itself is unambiguous, and in various combinations,

e.g., hiaendre, it is highly probable that no If grace-note is intended.

The question of the co and o, B or C, is a little more difficult in

theory, but in practice it will be found to narrow down to one or two

instances; the most common instance of this ambiguity is odro, which may

be either B grip C, or C grip C. It seems likely that this contusion is

the origin of this difference in existing settings of various tunes,

e.g., An Daorach Mhor (The Big Spree) Var. 1st and doubling, The Battle

of Auldearn, The Caries of Shigachin and many others. Campbell often

writes 'ho' for 'o,' obviously not intending a G grace-note, but to

avoid this ambiguity.

Time signature and rhythm are, I think-,

sufficiently shown to enable a trained player to find no difficulty in

playing; bar divisions are indicated by commas, and each part of each

tune is divided into lines numbered 1st, 2nd, etc. : and a repeat is

written at the end of the line to be repeated, thus : Two times or twice

over. ' 3 times,' etc., is often used in the MS. to refer back only to

the last comma, not to the beginning of the line. The smaller details of

time, which I will call " pointing," is a matter of greater doubt. I

have said above why I think Gaelic standards should be applied to the

pronunciation of the vocables, and my opinion is that the same applies

to this question in general terms: it can be said that as a rule the

vocables are separated into distinct words, the accent or stress (and in

this case the longer note) being represented as the first syllable of

the word (an almost invariable rule in Gaelic). Thus one gets hodarid

hiodarid—not daridho daridhio darid. Many exceptions can be pointed out

no doubt, but the above will serve as a broad rule.

It should be made clear to any reader of this

paper that it has been written in haste. Most of it is written from

memory after four and three-quarter years separation from MSS., books

and notes, and I have no doubt that mistakes will be discovered later.

Further, it does not profess to be complete, for there are some vocables

not included, the meaning of which is not yet clear to me.

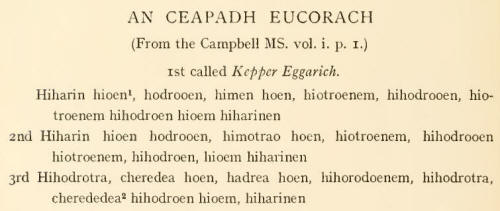

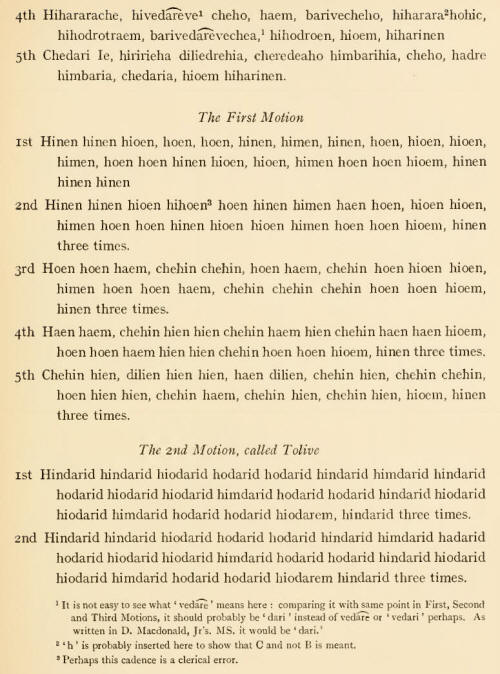

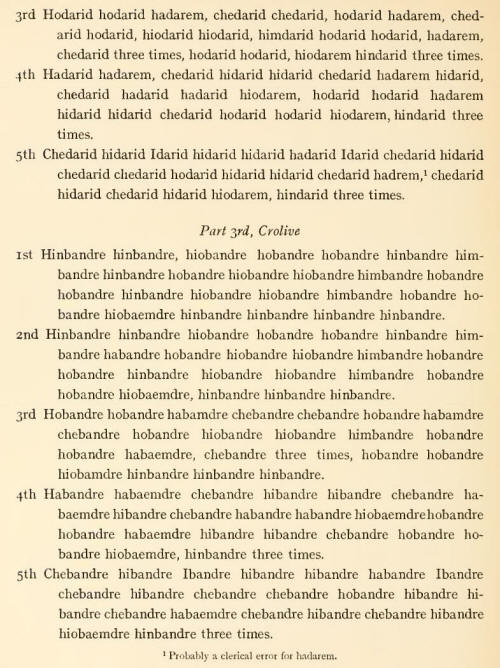

The two volumes of the MS. contain 169 tunes of

which I can trace in no other collection, printed or MS., 65 tunes :

moreover, many tunes which exist already in printed collections are

written in entirely different settings, and under different names from

those known by present day players. To illustrate this I have included

at the end of this paper the MS. style of An Ceapadh Eucorach

(translated as the "Unjust Incarceration"). This setting, apart from

smaller differences, contains one line in each part which, so far as my

knowledge goes, is unknown to-day, and which in my opinion is an

essential part of the theme, leading the 3rd line up to the musical

climax of the ordinarily accepted 4th line.' The names of the tunes as

written in the Index or as headings in the MS. present a very difficult

problem. Some are in English; some are in recognisable Gaelic; some are

in unrecognisable Gaelic, some give the first few notes of the tune, and

some are ludicrous inistranslations of Gaelic into English. Only

approximately 42 out of the total have anything like time names by which

the tunes are known to-day.

It is to be hoped that sonic day soon the whole

MS. will be printed, so that enthusiasts who have the time may really

get to work and unravel some of the conundrums which still remain so. I

have a feeling that the vocables used in so many Gaelic songs are

distantly related to canntaireachd, and research into this might

conceivably throw light on the larger question of the origin of

canntaireachd. It would also be interesting to know of any examples of

similar notations in foreign countries. But the main thing to be done by

all pipers at the present day is to make real attempts to discover other

canntaireacbd manuscripts : and the ideal should be that all MSS. now

known to exist or discovered at a later date should be made available

for comparison and information of other players this is best clone by

publication in as near the original form as possible, and failing that

by loan or gift to some responsible piping society, such as the Scottish

Pipers Society, The Piobaireachd Society, the Caledonian Pipers Society,

London, The Inverness Pipers Society, The Highland Pipers Society,

Edinburgh, or any other well-known society. This would ensure that the

information would get into the hands of those who can most easily

disseminate it.

|