The Scottish Military

Tradition in Canada

by Ian McCulloch

Men bred in the rough bounds,

the host that is trustworthy...

Men of elan and mettle

with blue blade in pommel...

Descendants of noble clans,

begotten of north men,

'twas their instinct in every action

to advance...

-- Duncan Ban Macintyre, 1725.

Regiments bearing Scottish

names, their ranks filled with men wearing the "bonnet, kilt, and feather"

have played an important part in Canadian military history whether they

fought as Scots in the British army with Wolfe, Amherst and Carleton in

the 1750's through to the American Revolution, or as Scottish Canadians in

defence of their own country.

Disbanded Highland soldiery settled in Canada over two hundred years ago

starting a military tradition founded on the strengths of their Scottish

heritage: bravery, devotion, and fortitude in distress. Today, according

to Stats Canada, there are over two million Canadians of Scottish descent.

The Scottish military tradition is generally associated with the

Highlands, home of the clans, where a tribal feudalism akin to our own

Canadian aboriginal peoples flourished with its own hierarchy of

chieftains. Highlanders were "men bred in the rough bounds", living off

the fish they caught in the lochs, the deer they hunted in the hills, and

the herds they tended to in strachan and glen or raided from their Lowland

neighbours. They were a hardy, intrepid race with all the attributes

needed to make good soldiers: courage, endurance, self-reliance and above

all, loyalty to one's leader and comrades. Scots had served as mercenaries

abroad since the days of the Romans when the British government in 1725

finally recognized the age-old adage that "it took a thief to catch a

thief". It raised a number of kilted independent companies to keep watch

on the Highland clans and discourage their proclivity for reiving cattle.

Clad in a black, green and blue government tartan, they became known as

the Freiceadan Dubh, or Black Watch. Several years later, as a move to

counter the growing tide of Jacobitism in the Highlands, a suggestion was

made that the government should consider raising several regiments of

Highlanders commanded by English or Scottish officers of "undoubted

loyalty" and officered by chiefs and chieftains of "disaffected clans".

Lord Duncan Forbes of Culloden wrote:

...If Government

pre-engage the Highlanders in the manner I propose, they will not only

serve well against the enemy abroad, but will be hostages for the good

behaviour of their relatives at home, and I am persuaded it will be

absolutely impossible to raise a rebellion in the Highlands.

Forbes' advice was only

followed in part. Only one regiment was formed, and this by bringing

together the scattered independent companies of the Watch to form the 43rd

Regiment (it was later renumbered the 42nd in 1749). They fought bravely

at Fontenoy on the continent and during the "Forty-Five" Rebellion, sagely

foreseen by Forbes, remained in southern England awaiting further service

overseas.

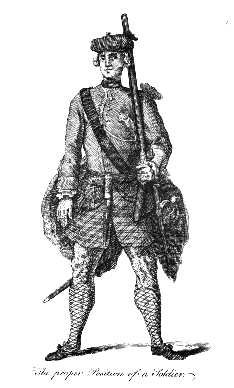

A

Black Watch private demonstrates "The Proper Position of a Soldier"

in a 1757 plate from Grant's

The New Highland Military Discipline.

(Credit: Author's Collection).

On the outbreak of the

Seven Years War in 1755, William Pitt adopted Forbe's ideas with

enthusiasm, leading to a policy which drained the Highlands of its best

men to fight England's wars in Europe and North America. During this

period no fewer than ten line regiments were raised, two of which, in

addition to the Black Watch, served in North America. They were

Montgomery's Highlanders (77th Foot) and Frasers' Highlanders (78th).

All three regiments made their mark in the year 1758, but in three very

different theatres of operations; The Black Watch in their heroic but

futile storm assaults upon the abatis before Fort Ticonderoga; the

Montgomery Highlanders forming the van of General Forbes' successful

expedition that captured Fort Dusquesne (now Pittsburg); and the Fraser

Highlanders taking part in the siege and capture of Louisbourg. Of the

three however, the 78th could rightfully claim to have been the first

Highland Regiment to have ever fought in Canada. They were not, however,

the first Scots!

Colonel the Honourable Simon Fraser of Lovat,

who led his Gaelic-speaking Highlanders to victory in Canada

at the sieges of Louisbourg 1758 and Quebec 1759.

(National Archives of Canada)

Many emigre Jacobites found

positions as officers in the French army before, during and after Culloden

and several were officers and soldiers in the Compagnies Franche de la

Marine fighting Indians before the 77th and 78th were raised or the

outbreak of the Seven Years War.

In 1759, Frasers' Highlanders formed up on the right of James Wolfe's

small army assembled on the Plains of Abraham and marched into Canadian

history books. At the end of the war in 1763, the 77th and 78th were

disbanded and every officer and man was offered a grant of land in Quebec

according to his rank. Thus the disbanded soldiery of these two units

became the nucleus of the first non-French settlers in Canada. And they

were not the last.

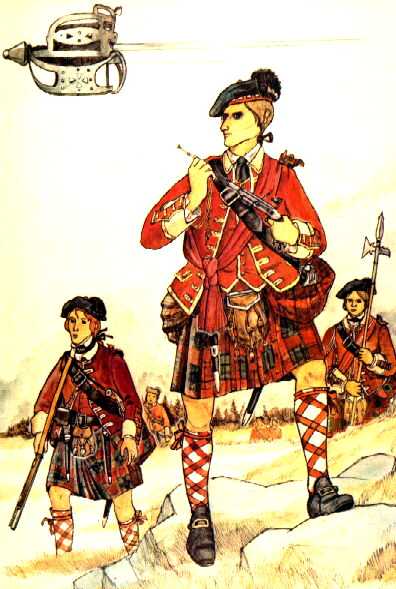

The Victors of Louisbourg and Quebec.

An artist's reconstruction of the uniforms of the 78th Regt of Foot,

Fraser's Highlanders, 1757-63. (L to R) Private, Officer and Sergeant.

(Credit: David M. Stewart Museum/Francis Back)

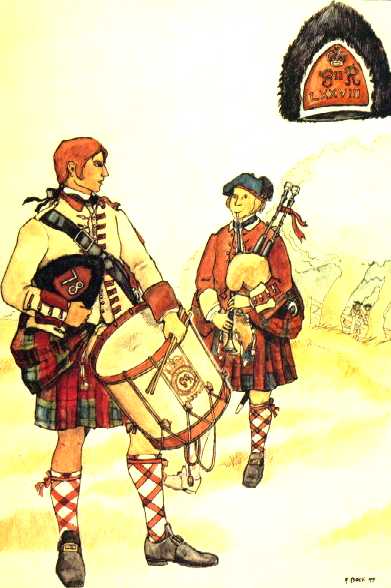

A Drummer and Piper of 78th Regt of Foot,

Fraser's Highlanders, 1757-63.

(Credit: David M. Stewart Museum/Francis Back)

Between 1770 and 1815, some

150,000 Highland Scots came to Canada settling mainly in Nova Scotia,

Prince Edward Island and Upper Canada. Most of them were displaced

crofters from the western Highlands and islands of Scotland, victims of

the infamous Highland Clearances. They were almost exclusively

Gaelic-speaking and many were Roman Catholics. For a time, Gaelic was the

third most-spoken language in Canada.

When the first shots of the American Revolution rang out at Lexington in

1775, the British government once again turned to the Scots for help. More

Scottish regiments were raised including one in Canada. On June 12, 1775,

General Thomas Gage issued orders to Lieutenant-Colonel Allan Maclean to

raise a regiment consisting of two battalions, each of ten companies, to

be clothed, armed and accoutred like The Black Watch and "to be called The

Royal Highland Emigrants". The idea was that the Emigrants ( the first

Scottish regiment ever raised in Canada) would find recruits amongst

former soldiers that had served in the 42nd, 77th, and 78th. As

inducements to enlist, each man was promised further grants of land at the

expiration of the hostilities and one guinea levy-money on joining.

Officer, 84th Royal Highland Emigrants, 1778,

(Credit: Author's Collection)

During the American

invasion of Canada, the First Battalion Royal Emigrants under Maclean

played a key part during the siege of Quebec 1775-76, repulsing General

Montgomery's attack on the city in which the American commander was

killed.

Other Scotsmen were raised as a regiment to serve King George south of the

border in New York state. A considerable number of Highlanders from

Strathglass, Glen Urquhart and Glengarry had emigrated in 1773 to the

Mohawk Valley and settled on the lands of Sir William Johnson,

Superintendant of the Six Nations. His son was commissioned as a Colonel

when forced to flee his lands and the Scottish tenantry that accompanied

him were formed along with other loyalists into a provincial regiment

under the name of The King's Royal Regiment of New York. The "Royal

Yorkers", as they became known, saw action in 1776 when they defeated the

Americans at Oriskany during the Saratoga campaign and participated on

several notable raids into their old neighbourhood, the Mohawk Valley.

Like the Royal Highland Emigrants, the "Royal Yorkers" were given land

grants in what is now Glengarry and Stormont counties in Ontario. Their

memory is perpetuated to this day by the Stormont, Dundas and Glengarry

Highlanders, a Canadian militia regiment headquartered in Cornwall,

Ontario.

The Scots who fought in the War of 1812 were predominantly the Highlanders

that lived on the banks of the St Lawrence from the Bay of Quinte right up

to Trois Rivieres and beyond. Though no Highlander unit in the strict

sense of the word was raised, every militia unit along the river was very

Scottish in character. A quick glance at the names commanding the county

militia regiments is revealing: Lt Col Alex MacMillan of the 1st

Glengarry; Lt Col Allan Macdonnell of Greenfield of the 2nd Glengarry; Lt

Col Thomas Fraser, 1st Dundas; Lt Col Allan MacLean, 1st Frontenac; Col

John Ferguson, 1st Hastings: Lt Col Matthew Elliot, 1st Essex; Lt Col

William Graham, 1st York; Col William Fraser, 1st Grenville; etc.

Following the war of 1812, a number of Scottish line regiments saw tours

of garrison duty in Canada including The Royal Scots, the 71st Highland

Light Infantry, the 70th Cameron Highlanders, the 78th Rosshire Buffs

(later Seaforth Highlanders, the 80th (Glasgow Lowland) and the 93rd

Sutherland Highlanders. With the creation of the Dominion of Canada in

1867, the days of British garrisons were numbered, and with the exceptions

of Esquimalt and the Halifax Citadel, the last of the regiments were

withdrawn by 1871.

Officer, 71st Fraser Highlanders, c. 1776,

(Credit: Author's Collection)

Fierce Look of Pride,

NS university students recreate annually the Scottish tradition

of the 1869 Imperial Garrison of Halifax at the Citadel.

Uniform is that of the Rosshire Buffs (78th Seaforth Highlanders).

(Credit: Parks Canada)

After 1815, Scottish

immigration to Canada increased in numbers and the pattern altered. Scots

from Lowland areas joined Highlanders in coming to Canada. Some 170,000

Scots crossed the Atlantic between 1815 and 1870, roughly 14% of the total

migration of this period. By 1850 however, most of the newcomers were

settling in United Canada rather than the Maritimes. The 1871 census shows

that 157 of every 1000 Canadians were of Scottish origin ranging from 4.1%

in Quebec to 33.7% in Nova Scotia.

It is no surprise then that when the British regiments left, volunteer

militia units sprang up to fill the vacuum. The Black Watch (Royal

Highland Regiment) of Canada rightfully claim to be the oldest Highland

unit in Canada having been created in 1862 and are reflected as such in

the army order of precedence. Bonnet, kilt and feather however, did not

come until some later. Its Regimental history reveals that the unit

started as a light infantry unit that evolved later into a "fusilier" unit

from 1862 to 1879. Both early iterations of the regiment had flank

companies dressed in tartan trews, but it was only on 10 May 1879,

according to the Regimental historian that the Black Watch's ancestor,

"The Royal Scots Fusileers", became "truly Highland Scottish in character"

with "all ranks wearing Highland doublets and trews". Four years later,

the unit had been completely outfitted with kilts and in 1884 were renamed

"The Royal Scots of Canada".

"Bonnet, kilt and feather!" -

The Rosshire Buffs (78th Seaforth Highlanders)

drill on the parade square inside Halifax's Citadel.

(Credit: Parks Canada)

"The Skirl of the Pipes",

A piper of the Rosshire Buffs (78th Seaforth Highlanders)

takes the place of a bugler and calls the soldiers to their duties

at the Halifax Citadel. He is wearing the Mackenzie tartan,

part of a military uniform authentic to the period 1869.

(Credit: Parks Canada)

On the declaration of

hostilities between Great Britain and Germany in August 1914, our

Department of Militia and Defence, ignoring existing militia units and

their traditions, enlisted men into a new series of numbered Canadian

Expeditionary Force (CEF) battalions. Canadian historian George Stanley

has stated that "...several of the CEF battalions were given Scottish

designations...almost as if Sir Sam Hughes and Sir Edward Kemp had read

the words of Duncan Forbes of Culloden or those of William Pitt."

The first major battle of the Great War involving Canadian Scottish units

was when French colonial troops broke and fled under a German gas attack

at Ypres early in 1915. The 3rd Canadian Infantry Brigade, comprised of

the 13th CEF Battalion (The Royal Highlanders of Canada, and today, The

Black Watch), the 15th CEF ( 48th Highlanders of Canada) and the 16th CEF

(The Canadian Scottish) was left dangling on the flank to receive the full

brunt of the German attack which they successfully repulsed despite heavy

casualties.

It is impossible to tell the complete story of all the Canadian Scottish

battalions in World War One therefore let the tale of one suffice as

representative of the rest. The officers and men of The Black Watch of

Canada fought in three battalions numbering some numbered 11,954 men and

winning 26 battle honours. Of those who served, 2163 were killed, 6014

were wounded and 821 were decorated. Of the latter, Four were awarded the

Victoria Cross out of the eight total awarded to Canadian Scottish units.

The Canadian militia was reorganized after the war in 1919. No new

regiments were raised, but many changed their names and were re-designated

as Scottish units. For example, in this way, the 20th Regiment (1866)

became the Lorne Rifles (Scottish) in 1931, then after a 1936 amalgamation

with The Peel and Dufferin Regiment, The Lorne Scots as we know them

today; the 21st became The Essex Scottish in 1927 (now the Essex and Kent

Scottish); the 42nd became The Lanark & Renfrew Scottish in 1927 (now re-roled

as an air defence artillery unit); the 43rd (1881) became the Ottawa

Highlanders in 1922 and in 1933 changed to the Cameron Highlanders of

Ottawa; the 50th (1913) and the 88th (1912) amalgamated to form the

Canadian Scottish in 1920; the 59th became the Stormont, Dundas and

Glengarry Highlanders in 1922; the 82nd became the PEI Highlanders in

1922; and, the 103rd became the Calgary Highlanders in 1924. The

Mississauga Regiment formed in 1920 lasted a whole year before deciding to

change its name to The Toronto Scottish in 1921.

When the Second World War broke out, the peacetime militia regiments were

mobilized intact, contrary to the government policy of the previous Great

War. The first blooding of Canadian Scottish units occurred on the beaches

of Dieppe, August 1942 when The Essex Scottish, the Cameron Highlanders of

Canada, and elements of the Black Watch went ashore into a hail of fire

with their comrades of Second Division. Out of the 5000 Canadians

embarked, only 2210 returned to England and more than 600 of those were

wounded: 900 had been killed and over 1900 had been taken prisoner, nearly

600 of them being wounded as well.

The following year, The 48th Highlanders from Toronto and The Seaforths of

Canada from Vancouver of the First Canadian Division landed in Sicily and

were later joined on the mainland by The Cape Breton Highlanders of 5th

Armoured Division for the long hard slog up the boot of Italy to the Po.

After their "D-Day Dodger" stint in Italy they rejoined their Canadian

Scottish brethren with other Canadian divisions in Northwest Europe.

Eminent military historian George Stanley notes:

When we read the battle

honours of the Scottish regiments which formed part of the Canadian

First Army, we read, in effect the battle honours of all overseas

regiments - Moro River, Ortona, Liri Valley, Hitler Line, Gothic Line,

Coriano Ridge,Caen, Borguebus Ridge, the Scheldt, Walcheren, Breskens

Pocket, Hochwald, Zutphen, Kusten Canal, Apeldoorn. These and many other

names are today part of Canada's military history, part of Canada's

military tradition...0ne of which we can be proud.

The post-war period to the

present day has seen many reorganizations and amalgamations of Scottish

militia units until now only 14 proud regiments remain on the Canadian

Army List. They are, in order of precedence:

For a brief spell, The

Black Watch were activated as a regular regiment with two battalions

between 1953 and 1970. The battalions saw service in Korea, Germany with

NATO forces, and on UN tours to Cyprus. With the advent of Armed Forces

unification and force reductions, the two regular force Black Watch

battalions were reduced to nil strength and the Third Battalion (Militia)

resumed its designation as Canada's senior Highland regiment. One

consolation was that the uniforms, traditions, and instruments represented

by the Black Watch's pipe bands were inherited gladly by the The Royal

Canadian Regiment, Canada's oldest and most senior regular infantry

regiment.

Pipes & Drums of the RCR

The Pipes of the Second Battalion, The Royal Canadian Regiment,

stationed at CFB Gagetown, led a Freedom of the City of Fredericton

parade.

They are the last vestige of the Scottish military traditon in the

Regular Force army. They wear Maple Leaf (Canadian Government) tartan.

(Credit: Author's Collection).

The Scottish military

tradition lives on in Canada, perpetuated primarily by the militia

regiments and the RCAF and RCR pipe bands. That tradition will live on to

the day that Canadians fail to be moved by the strains of the

Governor-General's piper playing his pibroch at our National War Memorial

in Ottawa on Remembrance Day. The significant contributions made by Scots,

not only to our military history, but to all facets of Canadian life, are

an integral part of our heritage. The words of Scottish professor, Dr

Blackie, voiced in 1900 have a special message for us all whether true

sons and daughters of auld Caledonia or no:

The greatest misfortune

that can happen to any people is to have no noble deeds and no heroic

personalities to look back to: for as a wise Present is the seed of a

fruitful Future, so a great Past is a seed of a hopeful Present.

This article by Lt Col Ian Macpherson

McCulloch first appeared in print in THE BEAVER: Exploring Canada's

History, Volume 73/4 August/September 1993.

Copyright (C) 1993; Lt Col Ian Macpherson McCulloch

|