|

It was to be expected that the new spirit of 'Renaissance'

would quickly come to have an effect upon people's attitudes towards the

church. They would ask themselves not just how they should write, or paint

or trade, but also how they should think, and what the human mind could

genuinely believe. From questionings came doubts; and from the doubts came

theories, alternative to long accepted beliefs, and these theories in due

course brought about the disruption of the church in Western Europe.

Initially there was a broad measure of agreement that the condition of the

church in several respects, called for reformation. Some of those who took

this view remained in the church to work for reform from within; others

came to the belief that no voluntary reform could be expected, and instead

broke away in the Protestant movements of Luther and Calvin. In short,

perhaps the most profound effect of the Renaissance was the disruption of

the church and of Christendom itself.

The Protestant movement had made

considerable headway in Europe before its effects began to show with any

great significance in Scotland, but once Protestant influences were

carried, in print or by word of mouth, into Scotland, their spread was

rapid. In any case, in Scotland, as elsewhere, criticism of the church was

not really new. In 1406 the Scottish authorities had burned James Resby

for heresy, and in 1433 a similar fate overtook Paul Crawar, while in the

1490s a number of people, mainly from the local gentry in Ayrshire, known

as the 'Lollards of Kyle', were investigated as to their beliefs and their

intentions.

During the reign of James V, a stern foe of

heretics, a number of executions occurred, the most famous being that of

Patrick Hamilton, burned at St. Andrews in 1528. Any martyrdom is likely

to produce converts, and it was truly remarked at the time that 'the reek

of Master Hamilton has infected as many as it blew upon.'

Yet heresy in doctrinal terms, however

vigorously preached by committed men, was not in itself likely to turn a

significant number of the general populace away from the church. Popular

hostility was rather provoked by perceived defects in the organisation of

the church and in the personalities and life-styles of its leading

officials. The wealth of the church - ten times that of the crown itself -

was a cause of discontent and envy from secular property owners; many more

were antagonised not by the mere fact of wealth, but by the obsession with

wealth and power and property which they believed ruled the actions and

conduct of leading magnates in holy orders. The contrast between luxurious

life and theoretical self-denial was particularly offensive to the many

who had to contribute to make possible the enviable life-style of the

higher clergy and the monasteries. David Lindsay, in The Three Estates,

introduces the suffering and oppressed poor man, ruined by the exactions

imposed upon him by the church in the collection of its traditional

sources of revenue. So envy bred hostility, intensified by the widespread

feeling that while the church's privileges had been well-sustained, the

balancing duties and obligations had dwindled. Any privileged person or

body is viewed with some measure of resentment, a measure which is

increased if the privilege is seen as unmerited.

Some of the faults of the church might

properly be blamed upon laymen whose cynical behaviour had helped to bring

it into disrepute. Kings and nobles had used their power to place members

of their families in church positions from which large incomes could be

expected. Sometimes the person appointed to the position had brought

competence and even - as in cases like Bishop Gavin Douglas and Archbishop

Hamilton - distinction to their office; but critics noticed more

immediately such appointments as those of James V's various illegitimate

sons to be Abbots of St Andrews, Holyrood, Melrose, Kelso, and Coldingham.

Even more to be condemned were appointments

like that of James IV's illegitimate son Alexander, to be Archbishop of St

Andrews while he was still little more than an infant. Such appointments

were seen not merely as devices to ensure comfortable positions for the

lucky youths as they grew up, but as devices enabling the crown to pocket

the revenues of the various religious houses while their titular heads

were still minors.

Also, there had developed a practice,

increasingly common from 1530 or so for the appointment of laymen, as 'Commendators'

to administer, and draw the income from, church estates and by the

mid-sixteenth century, the church was increasingly seen as being defiled

by corruption and nepotism in whose presence it was difficult to maintain

respect. Respect for the clergy was further diminished, as the life-style

of many made their vows of poverty and chastity laughable. Such personal

short-comings prompted contempt and derision among ordinary people who saw

the clergy as 'idle bellies' consuming much and contributing little.

Nor were all these grievances imagination

or propaganda, still less hindsight-prompted sectarian abuse. Archbishop

Hamilton made strenuous efforts in the mid-1550s to reform matters;

Cardinal Sermoneta, reporting to Pope Paul IV in 1556, and the Jesuit

emissary de Gouda, in 1562, write of 'unbridled licence', 'avarice and

neglect', and 'supine negligence'. In fact, few would now challenge the

opinion, that the church in Scotland in the early and mid-sixteenth

century, was in an especially unsatisfactory condition.

Yet there is one secular or political

reason for hostility towards the church. The crown, in the person of James

V, was committed to the suppression of heresy, but also to the maintenance

of the French alliance. After Flodden, much evidence is held to indicate,

the value of the French alliance to Scotland was increasingly questioned,

as France seemed to gain such modest benefits as the alliance yielded,

while for Scotland it seemed to bring only disaster.

To turn from the French alliance was, of

course, to abandon the main principle of Scottish diplomacy since 1295;

and to seem to betray so many past heroes. Scots soldiers had served with

great gallantry in the armies of Joan of Arc. John, Earl of Buchan, son of

the Regent Albany, had become Constable of France; the 4th Earl of

Douglas, had become, for his services, Duke of Touraine, and both died for

France in battle at Verneuil in 1424. So, the tradition was deeply

established, and James V vigorously displayed his pro-French zeal. In 1537

he travelled, it seems uninvited, to meet personally and to marry the

French princess Madeleine in Notre Dame itself; and when Madeleine died

tragically within the year, it was once again to France that he turned,

marrying Mary of Guise, not of the royal house but of the great family

which wielded effective political power in that country.

His loyalty to the French alliance brought

James to war with England in 1542, but disaffection with his policy was

largely responsible for the failure of his nobles to support him with any

real enthusiasm and instead to submit meekly to the shameful defeat at

Solway Moss. The French alliance it could be argued, had once again

brought defeat and now disgrace upon Scotland. Even James, who must

already have been a sick man, did not recover from the news from the

borders, and died heart-broken they said, in Falkland. He lived long

enough to hear of the birth of his one surviving legitimate child, Mary.

Even this event had its depressing aspect. Mary of Guise had already had

two sons, both dying in infancy, and James no doubt had hoped that the

expected child would be a son. When they brought him the news of his

daughter, he seems to have seen the beginning of the end of the Royal

Stewarts. 'It cam wi a lass; it will gang wi a lass,' he is reported to

have said, with Marjorie Bruce and Robert Stewart in his mind. This

daughter might rule, but any child she might have would be the child of

its father, and Stewart succession in the male line would end.

The recent experience in war probably

explains why the Scots did not entrust the Regency, now once more

necessary, to the Queen Mother, Mary of Guise. The French alliance was

rendered unpopular by defeat, and the regency was conferred instead upon

James Hamilton, Earl of Arran, grandson of Mary, daughter of James II.

Arran was next in line to the infant Queen Mary, and the Hamiltons lived

excitedly with this awareness for many years.

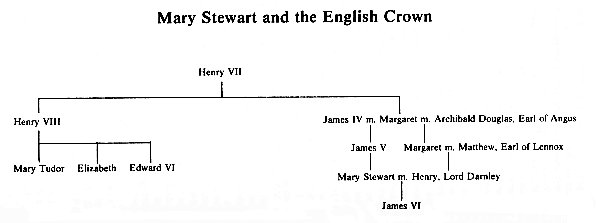

Another descendant of Mary, Countess of

Arran, was her great grandson, Matthew Stewart, Earl of Lennox. Lennox had

contracted a politically useful marriage with Margaret Douglas, daughter

of Margaret Tudor and grand-daughter of Henry VII of England. Lennox and

his masterful wife had an infant son, Henry Stewart, Lord Darnley. Mary

Stewart, Arran and Darnley, together with an illegitimate son of James V,

James Stewart, later Earl of Moray, were soon to become the leading

personalities in the political turmoils which lay ahead.

Arran's appointment as Governor was not

pleasing to the French whose favour naturally was extended to Mary of

Guise. For the moment Mary, and her close ally Cardinal Archbishop Beaton

of St Andrews, allowed Arran to shoulder the responsibilities of power in

a time of considerable trouble.

In July 1543, Arran negotiated with Henry

VIII the Treaty of Greenwich, whereby the infant Queen of Scots would

marry Henry's heir, Edward. This agreement was repudiated by the Scots,

and in 1544 and 1545 English armies ravaged the south of Scotland in

campaigns which grim humourists called 'The Rough Wooing'. Traditional

enmity to England and friendship for France naturally revived, but at this

point the pro-French party lost much goodwill because of Cardinal Beaton's

persevering attack upon heresy.

In March 1546, there was burned in St.

Andrews, George Wishart, a Protestant preacher and missionary, who had

made himself widely popular. The death of Wishart, like that of Patrick

Hamilton, aroused intense anger, directed especially against Beaton, who

had watched from his palace window as Wishart died. On 29 May, a gang of

Protestants, mainly from Fife, fearing that Beaton might move against them

and infuriated by Wishart's execution, broke into the Cardinal's palace

and murdered him. They then withstood a siege of several months, during

which the assassins in the castle were joined voluntarily by a small but

irascible Protestant preacher from Haddington, John Knox. Knox had acted

as a kind of bodyguard to Wishart and was naturally embittered by his

master's death. He demonstrated his opinions deliberately by joining the 'Castilians',

and was captured with them when French forces eventually compelled

surrender in July 1547. His punishment was to serve as a slave oarsman on

the French galleys in the Mediterranean for close on three years.

Meantime Henry VIII's death in 1547 had

brought his son Edward VI to the English throne. The English Regent, or

Protector, Somerset, who had been in charge of the 'Rough Wooing', now

returned to the attack, and inflicted upon the Scots under Arran the

crushing defeat of Pinkie, in September 1547. Arran's position was gravely

weakened, and the influence of the Queen Mother rose. She decided in 1548

that her daughter should go to France for safety, and in 1554 Arran

yielded the Regency to her, being comforted in his political misfortune by

the French title of Duke of Chatelherault.

Scotland therefore passed under the control

of a French Queen Regent. She was aided by a French Vice-Chancellor, a

French Controller, a French adviser, and a French army. There is little

wonder that tongues wagged to such effect that in 1555 the Scottish

Parliament passed an 'Act against speaking ill of the Queen's Grace and of

Frenchmen.' In 1557 the girl queen of Scots was married to Francis, the

heir to the French throne, entering into secret bargains which effectively

promised the virtual annexation of Scotland by France. Four members of the

embassy which conducted the discussions in France died on their way back

to Scotland, and there were suspicions that their deaths had occurred

because they were unwilling to support the French plan for Scotland's

future.

At this point the Queen Regent, who had not

given any signs of being a bigot or a persecutor, allowed the execution of

another Protestant martyr, the eighty-year-old Walter Milne. It seemed as

though the government was now bent on an offensive against the Protestant

faction and when the Queen Regent summoned leading Protestant ministers to

come to confer with her in Stirling, the Protestant leaders announced

their intention to defend their preachers by force of arms, and the 'Congregation'

as they styled themselves, assembled in military style in Perth in 1559.

There followed a period of virtual civil

war. Mary and her supporters with a French garrison, held Edinburgh and

Leith, and proved too strong for the Lords of the Congregation to dislodge

them. The Congregation, unable to deal with the French professionals by

themselves, appealed to the new Queen of England, Elizabeth, and an

English fleet arrived in the Forth, placing the French garrison in a

position of no little difficulty. Negotiations for peace began, and with

the death of the Queen Regent in June 1560, the French party was ready to

abandon its struggle. In July, under the terms of the Treaty of Edinburgh,

all foreign forces were withdrawn from Scottish territory, and the Scots

were left to work out just where power in the country now lay.

Looking back on these events it is clear

that three Scottish institutions - the Crown, the Catholic Church, and the

French alliance - were so closely involved one with the others, that they

would stand or fall together. Popular hostility to one would adversely

affect the standing of the other two. A Church already under severe

criticism, and a French alliance increasingly seen as being of dubious

value had combined to bring the Crown into virtual civil war. It now

remained for the Crown to become unpopular in its own right.

The death of Mary of Guise and the

withdrawal of French forces from Scotland left the initiative in the hands of the Lords of the

Congregation. In August 1560 the Scottish Parliament attempted a

settlement of the religious issues. A Confession of Faith, Protestant in

character, was accepted; Papal authority over the church in Scotland was

renounced and the celebration of mass was forbidden. The reformers had a

plan for the future structure and financing of the reformed church. The

First Book of Discipline, submitted to Parliament in 1561, proposed a

church, presbyterian in structure, financed by a share in the revenues of

the old church. But these proposals were rejected by Parliament, and no

clear plan for the new church was at this stage agreed.

This result was clearly a disappointment to

the doctrinal Protestants among the reformers, particularly, perhaps, to

the secretary to the Congregation, John Knox. Knox had distinguished

himself during the conflicts of 1559-60 by vigorous and inflammatory

preaching which had provoked at least one major disturbance, in Perth. By

1561 control of the Protestant camp lay rather with the nobles and gentry

who had emerged as the leaders of the Congregation, and who were much less

committed to root and branch reform than Knox. In 1561 a new complication

arose.

Mary Queen of Scots, in France since 1548,

and married to the Dauphin in 1558, had become queen consort in France

when her husband became King Francis II in 1559. In 1560 this young woman,

still only eighteen, was in a position of quite remarkable importance. She

was by birth Queen of Scots, and by marriage Queen of France. Most

important of all perhaps, not least in her own eyes, she was by one

reading of the rules - and a very justifiable reading at that - the

rightful ruler of England. A look at Mary's pedigree reveals why this was

so. Henry VIII's six marriages had produced three children. The child of

his first marriage, Mary Tudor, had reigned from 1553 to 1558, following

her half-brother Edward VI, child of Henry's third marriage. The son had

followed his father, quite in accordance with succession custom. His death

while still young and childless brought to the throne Mary, his older half

sister. But what should have happened after Mary's death was by no means

clear. In the event the throne had gone to Elizabeth, a child of Henry's

second marriage, but her claim was open to serious question. Even assuming

that she was Henry VIII's child - and even Henry sometimes appeared to

wonder - the marriage of her parents had been able to take place only

after her father's divorce of his first wife. Not only that, but though

Henry had married Anne Boleyn before their daughter Elizabeth was actually

born, the child had clearly been conceived in adultery, at a time when her

parents were decidedly not free to marry, and she was therefore by English

law illegitimate.

If this argument were to be accepted, then

Henry VIII's legitimate line would have been extinct, and the throne of

England would pass, rightly and properly, to the nearest family, the

descendants of his sister, Margaret Tudor, wife of James IV, mother of

James V and thus grandmother of Mary Stewart.

In short, for any who did not recognise

Henry's divorce, or who detected legal inadequacy in Elizabeth's birth,

Mary was in fact the true Queen of England.

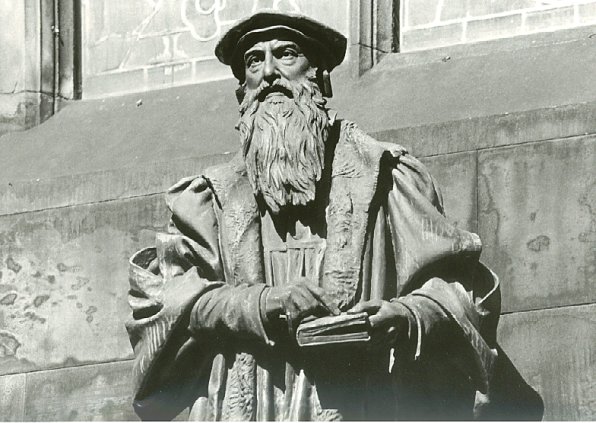

Statue of John Knox at the

High Kirk of St Giles, Edinburgh. (Photo: Gordon Wright)

And the next in line after her was Margaret

Tudor's grandson by her second marriage, Henry Stewart, Lord Darnley. So

it is not really helpful to speak or think of Mary as having some sort of

claim to the English throne, or to be thought of as just a possible

successor, some day, to Elizabeth. In the eyes of many, including probably

herself, she ought already to have been Queen of England. In this fact

lies the key to Mary's tragedy.

Mary's moment of greatness did not last

long. She was Queen in France for only one year, as her husband died in

1560 leaving her a nineteen-year-old widow at a court in which she had

shone, but which was now controlled by her mother-in-law, the masterful

Catherine de Medici, who had never liked this Guise girl anyway. So it

was, that in August 1561 Mary returned as queen to a Scotland changed

politically almost beyond recognition since she had last seen it as a

five-year-old child in 1548.

Daughter of a French mother, product of a

royal French upbringing, wife and widow of a French king, Mary was French

for all practical purposes. To return to Scotland - to exchange the

glamour and splendours of the French court for a fog-shrouded Leith and

the modest luxuries of Holyrood House, must have been for her an occasion

of great depression. What is remarkable, though too often ignored, is how

well she played her new role in the early days of her reign. She was

good-tempered and conciliatory towards the dominant Protestant nobles,

reaching with them a civil understanding that her religion was her own

private affair, which did not at all threaten the move towards

Protestantism which had occurred. Her chief guide was her half-brother,

Moray, a shrewd and capable politician who would have been an admirable

successor to his father if only James V had seen fit to marry his mother.

Between them

Mary, Queen of Scots, artist

unknown 'detail' (Scottish National Portrait Gallery)

Mary and her brother maintained a tactful

conciliatory policy, making for national unity; and Mary's personality,

lively and charming, contributed to greater tolerance and harmony all

round.

One nagging problem was always present.

Mary was only entering her twenties. She would without doubt marry again

sometime, even if only for political reasons. The question was, who would

be the bridegroom? Many anxious eyes watched to see what would happen.

France and Spain, seeing her as a Queen of England, were concerned about

her choice. Elizabeth, keenly aware of Mary's menace to her position, was

on the alert for any marriage which might further threaten her security.

At home the Hamiltons - between whose leader and the throne stood only

Mary - wondered if she might perhaps marry Chatelherault's son. Matthew

Lennox and Countess Margaret thought similar thoughts on behalf of their

son Darnley. Moray, reflecting on fate's injustices, knew that any husband

would oust him from his sister's side; Protestant lords feared, and

Catholic lords hoped for, a Catholic marriage which might begin to bring

the country back to the old faith. In 1565 Mary made her choice, a

disaster from which all her later troubles sprang. For what seem beyond

doubt to be purely romantic reasons, she married her cousin Darnley,

thereby antagonising everyone important except the Lennoxes. Moray and the

Hamiltons were embittered; Elizabeth saw in this marriage of her two

nearest heirs all the signs of a conspiracy, while to Protestants in

Scotland this Catholic marriage was a challenge.

Knox in particular denounced the marriage,

loudly and publicly. He had already had several brushes with Mary,

criticising her conduct on various occasions. She had tried to charm him

as she had all her other critics, and had tried to make him agree that a

Queen was not to be spoken to, or about, in a fashion which might suit

people at a humbler level. If Knox had any cridinticisms, would he please

meet her privately, and give her the benefit of his views? To this his

response had been, 'I am not appointed to come to every man in particular

to show him his offence.' In other words, public rebuke was for queens as

well as for dairy maids, a point of view which Mary could probably not

understand let alone accept. When Knox denounced her marriage, describing

Darnley as an infidel who would go far to banish Christ Jesus from the

realm (and) bring God's vengeance upon the country, Mary in a rage

summoned Knox and, towering over the little man from her own six feet in

height, she demanded, 'What have you to do with any marriage? Or what are

ye within this commonwealth?' Knox answered, 'A subject born within the

same, madam.' A leading modern historian has remarked that modern

democracy was born in that answer. He exaggerates slightly perhaps, but he

has a very real point.

There were here brought into sharp contrast

two opposing views of royal status and royal power, which were to dominate

the story of Mary's descendants from that moment until they lost the

throne forever. A monarchy bent on preserving and enhancing its own status

and powers came into increasingly bitter conflict with those who wished to

extend rights of participation. The confrontation between Knox and Mary

can be seen as the beginning of the great constitutional struggle which is

the story of the seventeenth century. Mary's son, James VI, carried

forward his mother's views and his son Charles I and grandsons Charles II

and James VII pressed them to the point of civil war and revolution.

The rest of Mary's story is briefly told,

though many writers have made volumes of it. Her marriage with Darnley,

offensive to so many, became within a matter of months offensive to her

too. He was, to put the kindliest possible gloss upon his conduct,

immature. Mary turned for friendship to her secretary David Rizzio.

Protestant extremists feared Rizzio's influence, and Darnley suspected

infidelity; so he and a Protestant faction murdered Rizzio in Mary's

presence, and in circumstances which left Mary convinced that they had

intended to cause the miscarriage of the child which she was shortly

expecting. Darnley then tried to return to Mary's good graces by assisting

in the attempt to punish the other murderers. Rizzio was killed in March

1566. In December his murderers were pardoned, and returned to Scotland,

where they might be expected to repay Darnley for his treachery.

Early in 1567 Mary appeared to reconcile

herself to Darnley, arranging for him to leave Glasgow, a Lennox

stronghold, and come to Edinburgh where she could be near him during an

illness which had come upon him. On 9 February she left her whining

husband ill in his temporary home at Kirk o Field House in Edinburgh,

while she went to a ball at Holyrood. During the evening Kirk o Field

House blew up, and Darnley's body was found in the garden, propped neatly

against a tree, strangled.

A Douglas group, followers of James, Earl

of Morton, were the probable culprits, but a suspect too was James Hepburn,

Earl of Bothwell. In April Bothwell carried out an apparent abduction of

the queen, whose friendship towards him had already caused gossip, and in

May they were married.

If the Darnley marriage had cost Mary

support, this latest act of unwisdom cost her her throne. The bereaved

Lennox, the twice-ousted Moray and most of the nobility now rose in

rebellion. To avoid bloodshed, Mary surrendered to the rebels at Carberry,

requiring only that Bothwell be allowed to go unmolested into exile, and

became a prisoner, guarded by one of her father's former mistresses, in

Loch Leven Castle. Her abdication was then extorted, in favour of her son

James VI, with Moray to act as Regent.

To remove Bothwell was one thing. To

enforce the Queen's abdication was another, and a powerful group of

nobles, Protestant as well as Catholic, returned to Mary's support,

achieved her escape from Loch Leven, and faced the Regent and his forces

at Langside. The Hamiltons fought for her, as did Argyle and Eglinton; and

even after her final defeat, Edinburgh Castle was held for her by

Kirkcaldy of Grange, who once already had experienced a siege when he

joined the murderers of Cardinal Beaton in St. Andrews Castle. Altogether,

in spite of all her errors of judgement, Mary was supported at the last by

nine earls and eighteen lords, who preferred her to the alternative before

them.

Mary in her flight thought obviously of

France, and her first attempt was to make for Dumbarton, in Hamilton

hands, from which she might escape by sea. But Moray's army barred the

road north and west, and she turned instead to seek asylum in England. As

a refugee, and then a prisoner, she remained for almost twenty years,

while Elizabeth, with busy impertinence, took it upon herself to inquire

into the Darnley murder and Mary's general conduct. Mary had been a threat

to Elizabeth since her birth, and even as a prisoner, a threat she

remained. Inept plots were mounted by English Catholics, prompting the

English Parliament to lay down the death penalty, not only for plotters,

but for the intended beneficiary of any plot. In 1586 the last - the

Babington Plot - was exposed, and Mary was revealed to have been in touch

with the plotters. For this she was condemned to death.

The Palace of Holyroodhouse,

Edinburgh. (Photo: Gordon Wright)

Elizabeth was unwilling to have an actual

sovereign executed as a criminal. She preferred murder, and tried to

persuade Mary's jailer to see to that, but he, with regard for the law

greater than that of his queen, refused. So there was no alternative left

to Elizabeth. Doing her best to make it all look like an unfortunate

accident, she gave her consent and the Queen of Scots was beheaded in

Fotheringay Castle on 8 February 1587.

Meanwhile in Scotland John Knox had

preached at the coronation of the child James VI in July 1567. In 1570 he

had to preach again, this time at the funeral of the Regent Moray, victim

of a Hamilton assassin. In 1572 he preached his last sermon in Edinburgh

on 9 November, and on 24 November he died. His last reading was from St.

John, chapter seventeen, finding in Christ's farewell to his mission and

his followers, an exemplar for his own. His task had been as he himself

put it, to instruct the ignorant, comfort the sorrowful, confirm the weak

and rebuke the proud, by tongue and lively voice. No doubt he was most

himself in instructing and rebuking, rather than in comforting and

confirming, because he was a positive and combative man in troubled times.

It is a pity that later sectarian

prejudices, or a public opinion widely indifferent to religious zeal have

led many to form a picture of Knox as a bigot, a sour sabbatarian, a

destroyer of joy and an enemy of beauty. His bigotry was no greater than

that of any committed partisan; he was, as his writings show, a man of

considerable humour, and the sourness of later Scottish religiosity was

the work and legacy of later men. Described as the one truly great man

produced from the people since Wallace, he has a much better claim than

most to the description. |