|

A good case could be made for regarding David

I as the most significant and greatest king ever to rule in Scotland. His

long reign 1124-53 saw the country undergo what one historian has called 'an

explosion of new ideas, policies and practices.'

He is traditionally most

famous on two counts; firstly that he brought into Scotland numerous

Norman knights to whom he gave generous land grants, creating virtually a

new aristocracy; and secondly, that he presided over the spectacular

growth in the wealth, property and influence of the church.

He obviously

saw in the Normans qualities from which government and society might have

been expected to benefit. The oldest surviving charter of his reign is

that which grants the lands of Annandale to Robert de Brus, whose family

origins were in the Cotentin area of Normandy. Similar land grants were

made to families like the Comyns, the Balliols, Lindsays and Grahams - all

of them providing personalities of significance in later years. In his

court and councils, these new men were prominent. Walter Fitzalan, son of

a Breton family, became Steward, with extensive lands in Renfrewshire and

central Ayrshire; and his descendants, taking his official position as a

family name, became the Stewarts who were to rule Scotland, and England

too, in due course.

Other important and enriching foreign influences were

introduced by the religious orders which also gained from David's

generosity.

Before he became king, David had invited a group of Augustinian

canons to establish themselves as a community in Selkirk. Their venture

was successful, and they moved to new quarters in Jedburgh in 1118. They

were the trail-blazers. In 1128 Tironensians came to Kelso, and another

Augustinian house was established near Edinburgh Castle. These canons were

particularly devoted to the veneration of the relics of the true cross,

and their new headquarters, dedicated accordingly, was named Holyrood. In

1136 members of the great Cistercian Order were invited to come from

Rievaulx in Yorkshire to take possession of new lands centring on Melrose;

while in 1150 the latest and, in the eyes of many, the most beautiful of

the abbeys of the east Borders, was founded at Dryburgh as a home for

Premonstratensian monks.

Where the king led, subjects followed, and

landowners endowed religious houses like Dundrennan and Sweetheart Abbeys

in the west Borders.

These monasteries and abbeys grew and prospered, as

did the communities around them - the Cistercians were always famed for

their skill in estate and land management - and they were able in turn to

establish branches, as it were, often far from their original base. Thus

Melrose had colonies at Newbattle and Coupar Angus, while Kelso was mother

house to later houses at Kilwinning, Arbroath and Lindores.

The economic

and cultural influence of these developments was immense and gave to

Scotland new international contacts as the influx of Norman landowners had

done. There was, of course, one snag. The lands given by David to Norman

knights and the religious orders, had come, in most cases, from land

Dryburgh Abbey. (Photo: Gordon Wright)

previously in the possession of the

crown. The time was to come when the wealth and property of the Church

exceeded that of the monarchs, one of whom remarked bitterly that though

King David was doubtless a saint, he was 'a sair saint to the crown.'

The

new landowners and the new church foundations might fairly be seen as

tending to internationalise and modernise the country. This claim can

certainly be made for another of David's devices - the burghs.

Villages and

towns, if they grow and develop naturally, do so for a variety of reasons.

In each of the royal estates there was always some point at which the king

might reside from time to time, and to that point were brought the

supplies which all the local tenants were obliged to provide as their

rent. Often the king was not even in residence; or at times there would be

more produce than he and his court required, and the surplus would be

disposed of, offered for sale or exchange in a kind of market.

The

advantages of a market are always quickly obvious to any community.

Trading - buying and selling - is the basis of any kind of economy which

rises above mere self-sufficiency. Markets attracted customers, and

customers were quickly seen as being ready to pay for the privilege of

setting up their stalls, and the king was able to ask that a kind of toll

or rental should be paid to him by each trader. Later, the king could

adjust matters slightly by giving to the citizens of these market towns

the right to charge these tolls for themselves, paying the crown an annual

or regular fee for this privilege.

Similar developments occurred in villages near to a castle,

or an abbey, or a monastery and were especially to be expected around a

harbour, or at a point on a river which could be reached by sea-borne

trading vessels, or a point at which the river could be crossed by ford or

bridge. Important Scottish towns have their origins in these developments,

Perth and Stirling for instance, on Tay and Forth; or Aberdeen, Dundee and

Berwick on the coast.

Over all this activity David presided, governing with

efficiency, using methods which he had learned from the Normans. The

country was, for the most part, divided anew into units called counties,

which a royal official, the Sheriff, would supervise. The Sheriffs and

their counties came under the further supervision of the king's Justiciar,

and royal castles were built at key points, where they did not already

exist, to provide the administrative and military centres from which the

Sheriffs and the Justiciar could work.

Scotland under King David was

powerful, even in relation to Norman England; and for most of David's

reign Scotland's border with England lay further south than before or

since, along the Tees in the East and incorporating the ancestral lands of

Cumbria. In addition David had gained, by his marriage to the daughter of

a former English Earl of Northumbria, extensive lands in the east midlands

of England - Huntingdon, Bedford and Northampton. These lands were

obviously valuable to the king, but his possession of them set on foot a

series of events which in the long run brought disaster upon his people.

Like anyone else holding lands in England, David did so as a

subordinate or vassal to a superior - the King of England. Feudal

land-holding involved a degree of ceremonial; and regularly, nobles and

knights had to present themselves before their king to swear loyalty -

fealty - and do homage. The ceremony involving kneeling in a defenceless

and submissive pose, intended to show the inferiority of the person

performing the ritual. David knelt, at one time or another, before Henry I

and Stephen, and his successors in their turn did homage for the family

lands in England. They all knew, of course, that the person kneeling there

was the Earl of Huntingdon. To the eyes of the English kings and

courtiers, the various Earls of Huntingdon looked remarkably like the

Kings of Scots. Kings of England had cherished the notion that they were

somehow superior to the Scottish kings, and had some title to their

obedience. Malcolm III for instance, had submitted to William I at

Abernethy in 1072 and to William II in 1091. These submissions, however,

were in reality admissions of temporary military defeat, and the Scots

kings had not yielded to the English notion that Britain held one real

king - the King of England - and a variety of lesser, so-called kings

including the King of Scots. But whether the King of Scots took it

seriously or not, the repeated acts of homage, performed over a long

period of time gave to the English kings an assurance of their right to

control not just Huntingdon but Scotland as well.

One historian has written

of King David, 'He had found Scotland an isolated cluster of small

half-united states, barely emergent from the Dark Ages; he left her a

kingdom, prosperous, organised, in the full tide of medieval life, and

fully part of Europe, as she remained through the rest of the middle ages

and some time after.' To write this is perhaps rather to under-estimate

the preparatory work begun by David's parents and brothers, but it is

certainly true that he had raised Scottish importance to a new and much

higher level than before.

Not only did Scotland now exist as a very

respectable little kingdom in the eyes of the outside world, but at home

too David had created a new unity. This was displayed when his son, Henry,

died in 1152, leaving three boys who were now David's heirs. David acted

quickly, having the eldest of his three grandsons, Malcolm, taken on a

royal tour around the kingdom, where he was everywhere presented and

acknowledged as David's successor. Within the year David was dead, but he

had done his work well, and his grandson came to rule as Malcolm IV with

no serious challenge.

The reigns of David's two grandsons, Malcolm IV and

William, contrasted in some respects very greatly. Malcolm reigned for

only twelve years, dying young, unmarried and childless. William enjoyed

the longest reign of any Scottish king - forty-nine years - and left four

legitimate children to provide for the succession.

William 'the Lion', a

man of action rather than subtlety, unwisely drifted into war with Henry

II of England. In the confused pattern of marches and skirmishes which

followed, William was surprised and captured by an English force.

Having

the King of Scots physically in his clutches, Henry was able to dictate

terms. At Falaise, in Normandy, as a prisoner, William had to give his

formal assent to the longstanding, but never admitted, claim of the

English kings to be the feudal overlords of the Scottish monarchs. This

treaty of 1174 was never to be forgotten by the English, and it coloured

relations between the two countries for as long as Scotland survived.

So,

in a sense, William's reign was disastrous for Scotland, opening the way

to centuries of war and suffering. He bought back his status in 1189,

paying Richard I the equivalent of a ransom in return for cancelling the

Treaty of Falaise, but no matter that Richard made this bargain, later

English kings when the chance arose, simply acted as though William's

submission at Falaise stood for all time.

For the rest of his reign William

governed Scotland with reasonable success; putting down a northern rising

which had attracted Norwegian support, chartering more burghs - including

Glasgow - and founding new religious houses, notably the abbey at Arbroath,

where in 1214 King William was buried.

His son, Alexander II, found himself

involved in the English baronial action against King John, which

culminated in John's reluctant acceptance of Magna Carta in 1215; and the

King of Scots was one of those whose grievances John promised to redress.

At one point it even looked as though the rebel barons might choose

Alexander as an alternative king to John, but their choice fell upon Louis

of France instead, and Alexander's chance of spectacular professional

advancement was gone. He had, in later years, a very up and down

relationship with John's son Henry III, but his energies were mainly

employed in dealing with domestic troubles.

Galloway and Moray, and their

various local ruling families and factions, were still capable of

mischief. Alexander employed a tactic, which later kings were to use also;

having found an apparently loyal supporter in these restless areas, he

then gave that supporter responsibility for maintaining good order in the

future. Thus in the north the Earl of Ross acted as the king's strong

right arm and in Moray he fostered the power of the Comyn Earls of Buchan.

Another branch of the Comyns played a similar role in Galloway, where they

later became closely connected with another family whose influence was to

grow in the area - the Balliols.

Also, Alexander had to meet unrest and

violence along the western coast, where from time to time the kings of

Norway, seeking to make more effective

Arbroath Abbey, burial place of

William the Lion and site of the Declaration of Arbroath in 1320. (Photo:

Gordon Wright)

their control over the Hebrides, would incite, or at least

take advantage of, local disturbances. To deal with such a threat, in

1249, Alexander led an expedition which succeeded in bringing Argyle under

royal control; but, whatever plans Alexander may have had to extend his

authority into the islands, he did not live to carry them out, dying on

the Island of Kerrera, near Oban, with his work incomplete.

The accession to the throne of an

eight-year-old boy, Alexander III, might at other times have been expected

to mean disunity, intrigue and weakness in the governing of Scotland. But

as it turned out, the unity and sense of common purpose developing from

the days of David I, proved sufficiently strong for the child-king's

status to be accepted without challenge and for the affairs of the kingdom

to be conducted efficiently by committees of officials, nobles and

churchmen until Alexander took effective personal control at the

comparatively advanced age of twenty. Given the later reputation of

Scottish nobles and courtiers for greed and treachery, their behaviour in

the decade after 1249 is quite remarkable.

Such intrigue as did carry with

it any threat of serious mischief came from King Henry III of England,

whose shifty and conspiratorial nature prompted him to attempt to draw

advantage from the presence of a child ruler in the neighbouring kingdom.

Henry had been in a position to influence the Scottish monarchy

since Alexander II had married his sister, such marriages after all being

intended precisely to create closer ties and interchange of influence

between the families and realms of the two partners. However, the

influence of Henry and English power upon Scotland had ended with the

death of Queen Joan, and Alexander II's re-marriage to Marie de Coucy,

mother of Alexander III. No doubt Henry now saw the possibility of

re-asserting his powers in relation to Scotland, and thus swiftly arranged

for the marriage of his daughter Margaret to the young Alexander.

So in

December 1251 Alexander and his leading courtiers travelled to York, where

on Christmas Day Alexander was knighted by the English king and on the

following day was married to that king's daughter.

It would appear that

Henry made an immediate attempt to benefit from the happy occasion,

accepting Alexander's homage for his lands in England, and going on

swiftly and smoothly, to invite the boy to do homage for his kingdom as

well. It may be that Alexander was quick-witted and shrewd far beyond his

years; it may be that his advisers had coached him well in what he might

expect in York. In any case, astonishing though it may appear, the

eleven-year-old Alexander responded that he had come to be married, not to

deal with such serious matters of state policy, on which he could not

speak without proper discussion with his Council.

Alexander and the kingdom

had both been well-served during the years of his minority by the various

men and groups who wielded power during those years. The whole period is

distinguished by an unexpected political maturity. The Comyn and the

Durward factions seemed able to live together and work together, sometimes

in control, sometimes not, but neither group was treasonous in its

purposes, and both, when in power, administered with whatever competence

they could command. It seemed as though the work of Malcolm III and David

I had at last been crowned with success, and that stability would be the

kingdom's reward.

Alexander himself behaved with confidence and skill. He

appointed to his Council the leaders of both major political groups, thus

emphasising the fact of unity. The young king and his advisers presided

over a period of economic advance, which they consciously encouraged.

Burghs grew in importance and increasing trade brought growing prosperity.

One Scottish burgh and port - Berwick - was handling trade worth 25 per

cent of the total trade of England; on the land, arable acreage and

production increased considerably, raising living standards of the people

as a result; and trade and agriculture alike were encouraged and protected

by the competence of Alexander's administration. Law and order - always

necessary for economic confidence - were guaranteed by the work of

sheriffs in the various burghs and shires; of justiciars in larger areas,

and by the king himself, who travelled regularly and extensively around

the country.

The one external threat to security which Alexander II had not

been able to remove before his death, was that posed by the remaining

Norse presence in the Western Isles and the constant possibility that a

vigorous Norwegian monarch might choose to breathe new life into Norse

ambitions. Just such a crisis developed as Alexander took personal charge

of his kingdom. He began by offering to buy the Norse-held islands from

the Norwegian crown, and when his offer met with no favour, he allowed

attacks by local Scots leaders to be made against the more accessible

parts of the Norse territory. The Norwegian king Haakon, a man of immense

character and prestige, was not likely to allow such challenges to go

unpunished, and in 1263 he led a great fleet and army to restore the

diminished power of Norway in the Scottish outposts of its empire, and to

compel more submissive behaviour from Alexander.

Haakon's fleet sailed,

reaching Lerwick in the Shetland Isles by the middle of July. By August he

was gathering with his subordinates and supporters at Skye and in the

Firth of Lorne. The reinforced - but delayed - Haakon sailed for Kintyre

and into the Firth of Clyde. The Island of Arran was occupied and Bute

overrun, while Scots and Norwegians talked terms of peace at Ayr. As the

talks went on, the year advanced and the weather became more unsuitable

for seaborne armies.

On 30 September westerly gales began to cause damage

to Haakon's fleet, anchored between the Island of Cumbrae and the Ayrshire

coast. The crews and warriors, on galleys driven ashore, were attacked by

the Scottish local forces under Alexander the Steward; and throughout 1

and 2 October, skirmishes took place along the shore at Largs, as the

Scots fought to repel the Norwegians who had landed. On 2 October, Haakon

himself came ashore to take charge, but the best he could do was to

achieve an orderly retreat from the shore back to his ships, which then

left the Clyde and began the long voyage home.

The Battle of Largs marked

the end of the old Norwegian domination of the western seaboard of

Scotland, not because the battle itself was of any major importance, but

because Haakon had been unable to arouse genuine support among the

islanders. They had long followed Norway's lead and many families were

more than half-Norse in their ancestry and traditions but, as the

generations had passed the geographical realities had come to affect man's

thoughts and feelings. MacDonalds, Macruaries and MacSweens were now

half-hearted at best in their loyalties to Norway, and the notion that

their future interests lay in association with Scotland was clearly

gaining ground.

So, the great king withdrew homewards. Depressed and ailing

he rested in Orkney, where in the Bishop's Palace in Kirkwall, he died.

The

Pencil at Largs commemorates the Battle of Largs in 1263. (Photo: Gordon

Wright)

The Bishop's Palace, Kirkwall, Orkney. (Photo: Gordon

Wright)

The

new Norwegian king, Magnus, accepted that Norway's day of supremacy was

over, and at Perth in 1266 a treaty gave to the Scottish king all

Norwegian territories on the Scottish mainland and throughout the Western

Isles. With this treaty, honourably observed by both sides, relations

changed and friendship grew where previously enmity had been normal. In

1281 Alexander's daughter, Margaret, married King Eric, Haakon's grandson,

and the relationship between Scotland and Norway was clearly intended to

remain close.

With his other powerful neighbour, England, Alexander

had maintained reasonably good relations, as long as Henry III reigned.

That shifty monarch, having made his early attempts to bring Alexander and

his kingdom under English feudal domination, seems to have abandoned such

schemes, contenting himself by treating Alexander - who was, after all,

his son-in-law - with apparently genuine personal affection; and when he

was faced with baronial rebellion, the Scottish court was clearly

sympathetic to Henry. But things were to change. In 1272 Henry died, and

his son Edward became king. Then, in 1275, Margaret of England, Alexander's

wife, also died, and Alexander was now dealing not with a reasonably

genial father-in-law, but with his ex-brother-in-law, Edward I who was a

very different man from his father and who had his own ideas for the

future of Scotland.

It was therefore with some concern that Alexander and

his courtiers travelled to England in 1278, to do homage for his English

lands. The old images of kneeling Scottish kings haunted English minds.

Alexander as a boy had avoided the trap set for him by Henry III. Would

the new English king make some similar attempt?

When the meeting took place

Edward and his ministers clearly meant mischief. Alexander swore to 'bear

faith to Edward . . . and will faithfully perform the services due for the

lands I hold of him.' In that, all versions of events agree. But the

Scottish records of the meeting state that Alexander added 'reserving my

kingdom'. At this the Bishop of Norwich is reported to have suggested that

the English king may claim the right to homage for that kingdom as well,

to which Alexander responded: 'No one has the right to homage for my

kingdom, for I hold it of God alone.' The Scottish version may be

doctored; the English version shows signs that it definitely was. However,

there can be no doubt that Edward had tried to reassert the English claim

that Scotland was merely a sub-kingdom, and, equally, no doubt that

Alexander had rejected any idea of acceptance of the English case.

By 1280,

then, Alexander might well be seen as the most successful of Scottish

rulers. Scotland's territory was not so extensive as it had been briefly,

under David I, but it was compact and stable. Scotland politically and

Scotland geographically, coincided sensibly. The long contest with Norway

was over. Relations with England were peaceable and courteous. Trade

flourished, the land prospered, and good order prevailed at home. The

future, too, looked bright. Alexander had two sons, both now grown men,

and a daughter, queen by marriage, of Norway. There seemed every reason to

feel that Alexander's legacy of success would pass safely onwards through

the generations.

Then, in 1281, David, the second son, died; in 1283

Margaret died also, leaving an infant daughter with the widower King Eric.

Suddenly tragedy had struck Alexander's family, and danger approached his

kingdom. In 1284 the heir to the throne, Alexander, also died, and the

immediate future for Scotland was a matter of concern. Still, the Scottish

state which Alexander had fashioned held firm. The Scottish parliament in

February confirmed the baby girl over in Norway as the legal heir to her

grandfather, showing a degree of responsibility and discipline which

testifies to the order and form which Alexander had given to his kingdom.

However, one heir only, and that a female child, was not enough to give

reassurance for future stability. Alexander, still only in early middle

age, must marry again, and build a second family to guarantee the future.

So, in November 1285 at Jedburgh, Alexander married Yolande of Dreux,

thereby linking himself in friendship with powerful French interests.

On 18

March 1286, Alexander held council in Edinburgh, and, the business over,

set off to cross into Fife to join Yolande at Kinghorn. The late afternoon

and evening were dark and stormy, and the king was urged to stay in

Edinburgh and wait for better conditions in the morning, but brushing

aside all such advice the king left for the crossing of the River Forth at

Queensferry. The ferry master there added his warning that the weather

conditions made the crossing too dangerous to be prudently attempted, but

even his professional advice could not deter Alexander from his purpose.

He teased the ferryman, asking if he was afraid to die in his king's

company, and under this kind of moral blackmail the ferryman gave way,

prepared as he said, 'to meet my fate in company with your father's son.'

The eight-oared ferry made slow progress in the teeth of the northerly

gale, but eventually reached safety on the northern shore.

By now it was

dark, and in the darkness and the gale, the master of the salt-works at

Inverkeithing, who had come to meet the king, now argued with his master

that he ought to remain in Inverkeithing till daylight. Having come

through the dangers of the voyage Alexander saw no reason to fear the mere

fact of darkness. He did ask for, and received, two local men to guide him

and his three attendants on the last leg of his journey eastwards to

Kinghorn.

As the king rode off into the darkness, Earl Patrick of Dunbar

was chatting in his castle with a local worthy, Thomas of Ercildoune - 'Thomas

the Rhymer' - popularly believed to have the second-sight, and thus the

power of prophecy. What would tomorrow bring, asked Patrick. 'Before the

hour of noon there will assuredly be felt such a mighty storm in Scotland

that its like has not been known for long ages past. The blast of it will

cause nations to tremble, will make those who hear it dumb, will humble

the high, and lay the strong level with the ground.' However impressed or

alarmed Patrick may have been, Thomas's fears seemed absurd when the

morning of the 19th dawned fair and grew fairer as the sun climbed higher.

Just before noon, as Patrick was preparing for his midday meal, a

messenger, urgent and desperate for audience with the earl, brought news

that his king lay dead on the shore at Kinghorn.

His journey in the

gathering darkness had led Alexander to a point where his horse lost its

footing, whether on a cliff pathway, or in soft and treacherous sand on

the shore, is not clear. By whatever accident the king was thrown, and

died with his neck broken from the fall.

So Thomas's storm broke. The King

was dead. His wife and his son's wife were childless. His children were

gone, and only the girl Margaret, now the girl-queen of Scots, remained of

the line which ran back through Malcolm Canmore to Kenneth MacAlpin.

In

those circumstances Scotland's institutions and political leaders were

going to be tested to the uttermost. Some institutions and some leaders

stood the test, some only for a time, some for longer, but Scotland could

never now be what Alexander and a secure monarchy might have made her. Not

only would things never be the same; they would never again even be

comparable. The steady, solid development which saw its peak in Alexander's

reign was halted, and was never effectively resumed.

Scotland's luck died

with Alexander at Kinghorn and never the slightest whiff of good fortune

was to come the way of the Scottish people for the next seven centuries.

It

was not long before people knew what they had lost; and the chronicler and

historian recording these days, saw and felt the emotions of 1286 and the

years which followed.

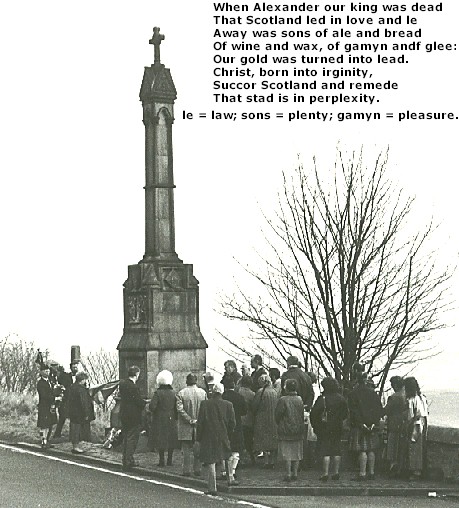

Annual Commemorative ceremony at the monument to King

Alexander III at Kinghorn,18 March 1990. (Photo: Gordon Wright)

|