|

By 1914 some 65 per cent of Scotland's people

lived in the central belt of the country between the Firth of Forth and

Clyde, and a steady drift from the countryside into towns and cities

continued, until, by the 1930s, 80 per cent of Scots were concentrated in

this area. The major employers were the 'heavy' industries - coal mining,

iron and steel-founding, shipbuilding and engineering. More than 200,000

families derived their livelihood from these industries, and a further

150,000 were sustained by employment in textile production. Thus more than

half the population was dependent upon labour-intensive manufacturing

industry.

In the late 1800s and into the twentieth

century, these industries were earning large profits, and great wealth

came to the owners, who enjoyed, in late Victorian and Edwardian times,

life-styles enviable for leisure and luxury. Unfortunately, though

individual acts of charity were frequent, there was no official social

conscience; and, in the presence of great riches, industrial workers lived

lives governed by low wages, long hours and frequently unhealthy and

dangerous working conditions. Away from the workplace, living conditions

were, as came to be realised, a national disgrace. Housing, whether

provided by employers or by builders planning to draw rents, was generally

cheap in construction, poor in quality and grudging in space. If employers

had provided high-quality housing, then their profits would have suffered.

If builders had offered high quality rented homes, a low-paid workforce

could never have paid the rents required. So, buildings were crammed into

confined sites, often cheek-by-jowl with colliery and yard, factory and

foundry; rooms were small, and around 53 per cent of families, no matter

how numerous, lived in houses with one or two rooms. Indoor sanitation was

absent or shared, and the effect of these conditions upon the health and

life-expectancy of the people was bound to be damaging. Typhoid fever and

even cholera survived into the twentieth century; epidemics of diphtheria

and scarlet fever were virtually annual, and tuberculosis killed

thousands. Poverty led to malnutrition, and diseases caused by diet

deficiency, like rickets, were common. To make matters worse, the houses

were themselves aging, and new building was quite inadequate to provide

homes for the rising population between 1850 and 1900.

To make matters worse, though few could

have realised it, Scotland's days of industrial success were already

numbered. The appearance of economic success endured and examples of

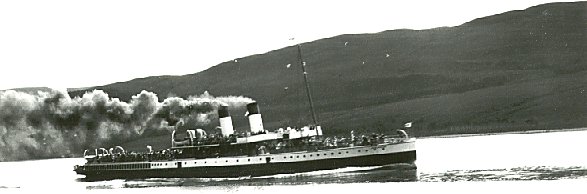

technological excellence (such as the building of the first

turbine-powered steamer, King Edward in 1901) occurred, but the basis of

Scotland's role as one of the world's workshops was weakening.

The resources of iron and coal upon which

industrial growth had been founded, had been, or were becoming, exhausted.

Many countries were able to exploit resources far beyond those available

in Scotland, and were also better placed geographically to manufacture and

trade. These emerging competitors commonly employed modern technology,

having learned from and improved upon Scottish - and English - exemplars.

Scotland's industrial experience proved the truth of Andrew Carnegie's

remark that 'pioneering don't pay'.

The King Edward sailing on

the River Clyde. (Photo: G E Longmuir)

To a great extent, therefore, decline arose

from realities of mineralogy, geology and geography, for which no one can

be blamed. Criticism can, however, be made of the owners and managers who

persevered with old-fashioned equipment and methods, preferring unbroken

production in the present to the prospect of greater productivity in the

future.

Also, as had been the case in the 1700s,

men who met with economic success in their chosen field tended to reward

themselves by abandoning that field and adopting instead the life-style of

leisured aristocrats. In Scotland's industrial heyday her industries were

planned and operated by men who were technically expert, or, at least,

well-informed. Men like Lord Kelvin could spend mornings researching and

lecturing on the theories of physics and engineering, and the afternoons

in the engineering shop, applying these theories to the practical task of

producton. But as time passed, owners became remote, mere investors or

administrators, detached from technological experience or experiment. The

managers to whom they left the day-to-day running of industry, all too

often showed the practical man's contempt for theory - 'mere' theory as

the revealing phrase puts it. The close integration of theory and practice

characteristic of the rise of Scottish industry - the tradition of James

Watt and Lord Kelvin, and of Robert and David Napier, the virtual creators

of the Clyde's greatness as a centre of shipbuilding and marine

engineering - gradually disappeared.

This industrial decline was not, of course,

clearly apparent at the time. Only in later years when statistics became

available did it emerge that Scottish heavy industries reached, in 1913, a

peak of production never to be achieved again. The decline was halted,

temporarily, by the boost to productivity given by the Great War, but by

the 1920s Scotland was distinguished by persistently high rates of

unemployment and similarly high rates of emigration. The population was

static and aging, and, in the post war world, the Scottish economy was

clearly sick and failing.

Inevitably these developments had political

consequences. Scotland was usually overwhelmingly loyal at election times

to the Liberal party. That party was supported by employers and workers

alike in industrial areas, while in the rural constituencies and in the

Highlands, the influence of the Free Church, often victimised by Tory

landowners, was exerted in the Liberal interest.

Towards the end of the century however,

things began to change. The Liberal commitment to Home Rule for Ireland

led to a split in the party, and to the formation of the

Liberal-Unionists. This group - still Liberal in terms of economic theory -

drew support from Protestant industrialists, businessmen and others of the

middle-class, unwilling to support any diminution of British sovereignty

and hostile to the placing of Ireland's Protestant minority under an

all-Irish and, therefore, overwhelmingly Catholic parliament in Dublin. As

a result, the number of Liberal seats in Scotland fell from 57 in 1885 to

39 in 1886. The Conservatives, who won only 10 in 1885, won 12 in 1886,

and enjoyed the support of 16 Liberal Unionists.

As more working men joined the electorate,

and as new issues like high tariffs and the threat of more expensive food

arose, Liberal strength momentarily revived, and in the elections between

1906 and 1910 the Liberals enjoyed something like their old dominance.

Events during and immediately after the war, however, disrupted the

Liberals who suffered a fatally damaging split into rival factons. At the

same time the ordinary voters, seeking political action to fulfil their

hopes and remedy their grievances, began to turn to the Labour Party.

The basic idea, that working people ought

to have, and to support, a party which was specifically theirs,

preoccupied with issues relevant to them, was as old as the Chartists of

the 1830s and 1840s. The idea revived in the 1880s in Scotland, with the

formation of the Scottish Labour Party. This venture did not long survive

the departure of its moving spirit, James Keir Hardie, to England, where,

in 1893 Hardie and others formed the Independent Labour Party. This party,

combining with some socialist societies, and with the support of a number

of Trade Unions, formed firstly, the Labour Representation Committee, and

then the Labour Party. This new party won two Scottish seats in the

General Election of 1906. Its strength remained modest, seven seats being

won in 1918; but in 1922, as the Liberals destroyed themselves by internal

feuding, Scotland saw the election of 30 Labour members (to the Liberals'

16, Liberal Unionists' 12 and Conservatives' 15). The Liberals rallied

briefly in 1923, but thereafter the Labour Party became the preferred

refuge of anti-Conservative voters.

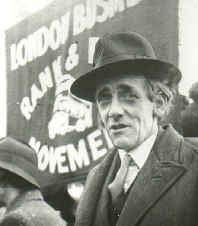

The MPs elected in 1922, characterised as

the 'Red Clydesiders' in the press were, in these early days, an

impressive contingent, representative of working class aspirations not

only to power, but to dignity and culture and respect, which had been

growing for thirty years and more. Men like John Wheatley and Tom

Johnstone were to prove themselves in Cabinet office. James Maxton, though

never holding any executive responsibility, was throughout his career a

loved and admired orator and tribune of the people. George Buchanan had a

political career long enough to allow him to make a valuable contribution

to the 'Welfare State' legislation of 1945-50. Not all important figures

were in Parliament or enjoyed successful political careers. One man, seen

by later generations as deserving of the greatest respect, was John

MacLean, a Glasgow school-teacher who taught and preached the values and

merits of socialism, suffering imprisonment and persecution culminating in

his premature death.

John MacLean. (Photo:

Glasgow Herald) | James Maxton. (Photo: Glasgow Herald)

Such men were the main personalities in

Scottish politics in the years of industrial strife and political change

which followed the war.

Strikes in the coal-fields in the 1920s had

brought great suffering and apparent defeat to the miners, fighting

against attempts to worsen their conditions of employment. In 1926 the

miners took the lead in the General Strike, and persevered in their

resistance for a year after their allies in other unions had given up.

It was difficult to maintain the rights and

interests of industrial workers as post-war unemployment mounted,

culminating in the experiences of the Depression which struck in 1929.

Hardest hit were the industries upon which Scotland especially depended -

shipbuilding and engineering, for whose products there was now no world

market. Demand for coal and steel thus fell, and as workers thrown idle

struggled to live within their means, demand for furnishings, household

goods, clothing and similar products fell also, and the whole population

was caught in a web of poverty and fear of poverty.

The Labour government which had taken

office, with Liberal support, in 1929, could not agree upon a policy to

meet the crisis. Its leaders co-operated in the formation of a 'National

Government' supposedly all-party but in reality dominated by

Conservatives, in 1931. In that year a General Election gave that

government a huge majority, as voters turned in panic to the methods,

financial policies and presumed expertise of the Conservatives. In

Scotland 58 supporters of the National Government were elected, with only

8 Liberals and 7 Labour members surviving in opposition.

Despite this apparent collapse, the Labour

Party in the long run benefited from the events which followed. Relief

payments, given as unemployment insurance benefit for some weeks, and then

as 'National Assistance' or 'dole', were ungenerous and grudging; and dole

payments were attended by harsh and humiliating surveillance as the 'Means

Test' was applied, with inspectors empowered to enter homes and pry into

the circumstances (and even the cooking pots) of the unemployed to ensure

that their dependence upon relief was genuine and total. So, though the

Depression had, initially, driven voters into the arms of the

Conservatives, the memory of the 'Means Test' became a great national

folk-myth from which the Labour Party was ever afterwards able to draw

advantage. A determination never to return to the conditions of the '30s,

and never to permit mass unemployment, was fundamental to Labour's

policies until the 1970s.

The National Government did take measures

to revive the economy. Regions of severe unemployment were designated 'Special

Areas', and industrial estates, producing such items as clocks and

electrical goods were established in places like the Vale of Leven,

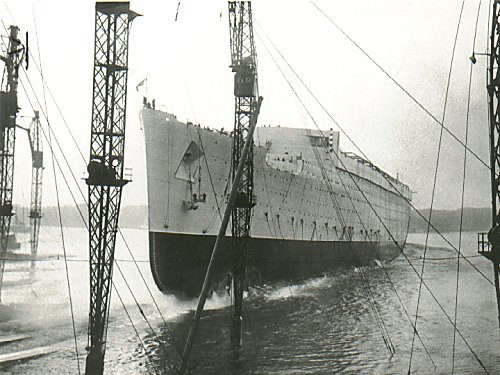

Hillington near Glasgow, and in Dundee. Symbolic of the government's

willingness to use state funds to revive industry, was the provision of

finance to enable work to restart upon the great new Cunard liner, begun

in 1930, which had lain rusting at Clydebank since 1931. In 1933 work

began again on this vessel, Yard number 534, which was launched in

September 1934 as the Queen Mary.

Despite these efforts, the new industries

came nowhere near to absorbing the numbers of unemployed workers, and only

the approach of war and the rearmament programme, which revived the heavy

industries, ended the years of idleness.

Scottish factories, yards and foundries

made a massive contribution to the British war effort, while the Clyde

estuary became the major anchorage for merchant ships arriving in convoys,

bringing food, materials and troops from around the world, especially from

America and Canada.

Britain's capacity to survive depended upon

the Atlantic routes being kept open, and Greenock was strategically placed

to shelter and service warships and merchant ships engaged in the Battle

of the Atlantic. Though Scotland as a whole never came under sustained

attack from the air, sharp attacks in March and May, 1941, virtually

destroyed Clydebank and inflicted heavy damage and casualties upon

Greenock.

Launching of the Queen Mary

at Clydebank. (Photo: Glasgow Herald)

The waging of modern war had brought the

people under closer government control than ever before. Conscription and

direction of labour, the organising of civil defence services, and

rationing of food and clothing, all entailed centralised decision-making

and centralised administration. The experience of wartime merely rounded

off a tendency towards centralisation and a gradual diminishing of local

distinctions which had been progressing throughout the century. More

aspects of life were seen as being 'the government's business', and were

subject to parliamentary decision and legislation - pensions, insurance

arrangements, housing standards for instance. Technology had made such

changes in communications that communities, which for centuries had lived

a unique life of their own, now were linked with distant places by road,

rail and sometimes air; their people read the same newspapers with the

same news and the same advertisements as were read by people several

hundred miles away; they listened to the same radio broadcasts, and viewed

the same films, and they could pursue social or economic discussions over

the telephone. In all these ways the people of Scotland were being

influenced into feeling an identity not only of interest, but of

personality, with all other parts of Britain. Labour's nationalisation

programme after 1945 centralised control of transport and major industries

in London, where the headquarters of banks and private industries already

tended to be.

Both major parties governed on the

assumption that Britain was, and ought to be, a centralised unitary state;

and both played down, for their different reasons, any lingering notion

that Scotland had any special identity in the modern world. For

Conservatives, Britain commanded patriotic loyalty, while the Labour party

thought in terms of class rather than nation. Labour had once shared the

old Liberal commitment to Home Rule, but, after 1945, Mr Attlee, the

Labour Prime Minister, explained that since Scots now enjoyed a Labour

government they had no need for Home Rule, and the commitment was

abandoned.

Political support for Home Rule had existed

after a fashion ever since the 1790s. As the 1800s proceeded, the Liberal

Party and early Labour pioneers were pledged to Home Rule. Pressure groups

grew and withered, but by 1920 there was ample reason to assume that, with

the Liberal Party in ruins and Ireland in revolt, Scottish Home Rule was a

mere dream.

Then in August 1922, there appeared The

Scottish Chapbook, in which the young poet Christopher Murray Grieve

demanded that Scots writers should begin to 'speak with our own voice for

our own times.' They should engage in a serious examination of profound

themes seen through Scottish eyes. Thanks to Grieve - or 'Hugh MacDiarmid'

as he called himself - and a generation or more of men and women inspired

by his example, Scottish writing ceased to be provincial and trivial as it

had become for some fifty preceding years, becoming rather the source of a

new national intellectual reawakening, reminiscent of the days of the

Enlightenment. What followed might be unfamiliar by English standards, but

in Europe and Ireland a cultural revival followed by political action was

a familiar experience.

The Duke of Montrose,

Compton Mackenzie, R B Cunninghame Graham, Christopher Murray Grieve,

James Valentine and John MacCormick at the first public meeting of the

National Party of Scotland, St Andrews Halls, Glasgow, 1928. (Photo:

Glasgow Herald)

Several organisations favouring Home Rule

functioned in the 1920s. The Home Rule Association had indeed been formed

in the 1890s; and it was now joined in its work by the Scots National

Movement and the Scots National League. The former was profoundly

influenced by cultural developments, while the latter was more anxious to

get on with the work of building up a force which could challenge the

existing political parties at election time. Just as the Labour Party

emerged when enough people saw the need for a class to have a party of its

own, so now the League based its appeal on the need for a nation to regain

the power to devise policies and arrange priorities in the best interests

of the people of that nation. These and other groups combined in 1928

(following upon the rejection of a Home Rule Bill in Parliament in 1927),

to form the National Party of Scotland; and later, after another accession

of support, the Scottish National Party.

The new party, after some initial doubts,

followed the strategy line of the Scots National League, and proceeded to

challenge the established parties at the polls, with results varying from

the ridiculous to the reasonably encouraging. The war was a setback for a

party trying to capture public attention, and the party's prospects were

not improved when a powerful faction abandoned the policy of

election-fighting, and adopted instead the older tactic of seeking to

influence existing parties to adopt measures which tended towards eventual

self-government, at least on all matters of domestic policy.

This breakaway group and its leader John M

MacCormick, a founder and long-time secretary of the Scottish National

Party, met with considerable success in the late 1940s and early 1950s.

They organised a series of annual National Assemblies, and produced the 'Scottish

Covenant' inviting signatures of support from all who would pledge

themselves to place Home Rule above partisan loyalties. Some two million

signatures were secured, but the Covenant Association had no means of

compelling politicians to respond to moral pressures. The politicians,

with cold cynicism, responded that only votes cast at General Elections

were acceptable as indicators of the electorate's wishes. The initiative

on the Nationalist side was thus restored to the SNP which had remained

committed to the election process. They had indeed enjoyed their one

success when in April 1945, at a by-election in Motherwell, Dr Robert D

McIntyre became the first ever Scottish Nationalist MP.

The post-war years were bleak for the SNP,

as the Covenant commanded attention from friendly countrymen, and when

party political loyalties for most took precedence over national

sentiments. But gradually political developments began to play into

Nationalist hands.

The Labour government of 1945 became

unpopular surprisingly quickly. Though the feared post-war unemployment

did not materialise, voters were indignant at the years of hardship and 'austerity'

which had followed the war, instead of the joyous comfort which many had

thought would come with victory. Surviving the 1950 General Election by

the skin of its teeth, the Labour government fell at the next hurdle, the

election of 1951. There followed thirteen years of Conservative

government, and Conservative support in England rose steadily at the

elections of 1955 and 1959. In Scotland however, the Conservatives reached

a peak of success in 1955, winning thirty-six seats to Labour's

thirty-four, but declining fairly rapidly in subsequent elections.

Scottish voters were in fact beginning to behave in a very different

fashion from their English counterparts.

Dr Robert MacIntyre, the

first SNP MP. (Photo: Gordon Wright)

The reasons for this divergence lay in the

economic policies pursued by the Conservatives and their consequences. As

the government sought to free the economy from the constraints which

Labour had seen fit to impose upon it, there were recurring crises as the

economy around London expanded rapidly and inflation threatened. At such

times the Treasury would impose restrictions, growth would slow down and

inflationary pressure would ease and all was then thought to be well. But

in Scotland, growth had hardly begun when restrictions were imposed, and

increasingly it seemed to many that one policy did not really meet the

needs of different parts of Britain. Also, to an increasing extent

Scottish factories were branches of English firms. When times were hard

and these firms felt the need to economise they would close their branches

and draw back towards their centre. The result for Scotland was recurring

outbreaks of unemployment and feelings of injustice and discrimination.

Reading the political signs and responding

to the decline in their support, the Conservatives by 1960 had begun to

try to placate Scottish opinion by abandoning their insistence upon one

single policy for all, and instead extending special favours to Scotland.

The car industry, lost to Scotland since the early 1900s, was virtually

directed by government pressure and incentives, to Linwood. A road bridge

over the Forth, long dismissed as an idle dream, became a reality, and a

Tay road bridge was also sanctioned.

All was politically too little too late

however, and Scottish voters gave decisive support to Labour in 1964 and

1966 when Scotland returned 43 and then 46 Labour members to the

Conservatives' 24 and 20.

In 1966 Scottish voters clearly trusted

Labour to extend prosperity to Scotland, and their disappointment was

intense when the new Labour government promptly faced yet another economic

crisis, which they sought to meet by using the same methods as those

employed by the Conservatives. At this moment of maximum disillusion with

both political parties a by-election was called in Hamilton. This was seen

as a safe Labour seat. It had been held for Labour even in the disaster of

1931, but now, in 1967, it was won by Mrs Winifred Ewing of the Scottish

National Party with a majority of 1799.

It was widely remarked after this event,

that Scottish politics would never be the same again. Political parties,

television companies and newspaper owners all fell over themselves to show

interest in, and concern for, Scottish sensitivities and ambitions. It was

all rather hectic, and it didn't last. In 1970, though Scotland supported

Labour loyally, and Mrs Ewing lost her seat, a Conservative revival in

England brought them a victory which few had expected or predicted. The

SNP suffered a setback in its progress, but it managed to keep a

parliamentary presence with the election of Donald Stewart in the Western

Isles constituency.

At this point fate took a hand, and the SNP

enjoyed a dramatic upturn in its fortunes. The argument against the SNP

put forward on doorsteps by Labour and Conservative canvassers was

essentially that Scotland was too small, too poor and too inexperienced

for its people ever to contemplate independence. The Scottish voters had

obviously agreed with this assessment. But in 1970 oil companies

prospecting in the North Sea found reserves of first gas and then oil. Oil

in modern times has an almost magic quality, linked as it is in the public

imagination with the spectacular wealth of American tycoons and Arab

potentates. The oil was admittedly on the continental shelf in

international waters, but it was in a sector allocated by international

agreement to Britain, and it was nearer to Scotland than to anywhere else.

The SNP gleefully proclaimed 'It's Scotland's Oil', and Britain's

politicians found that Scotland could not be made to seem too poor for

independence any more. They did their best. They argued that the oil

belonged to the oil companies and not to Scotland, ignoring the real point

which was not ownership but the right to tax and draw royalties. They

argued that there was only a tiny amount of oil, and that silly Scots were

getting excited about nothing, but time proved that that argument was

erroneous. Becoming subtler they then appealed to the Scots' better

nature, encouraging them to feel ashamed and greedy if they were to

persevere in their claim to the oil. The SNP meantime hammered away on the

theme of the marvellous things which could be done for the Scottish

economy and society with the revenues from the industry.

In 1972 and 1973 the SNP came close to

victory in by-elections in Stirling and Dundee East before winning another

in Govan. In February 1974 seven Nationalist members were returned at the

General Election, and when later that year the minority Labour government

sought a safer mandate to govern, the Nationalist contingent rose to

eleven.

That election was crucial, and though many

Nationalists were delighted with their progress, their success was more

apparent than real. The Labour Party had managed to retain its seats in

Scotland, though they had to promise a Scottish parliament and in other

respects steal the Nationalists' thunder. Between 1974 and 1979 the SNP

was out-manoeuvred as parliamentary experts dragged out interminable

discussions on the Labour plan for a Scottish Assembly. The SNP helped in

their own downfall by innocently acting as though the fight was won, and

they could enjoy the luxury of ceasing to make greedy noises about oil,

and turn instead to talk of problems such as the plight of single-parent

families.

Meanwhile the Labour leadership found that

they could not command the voting loyalty of a number of their English

members. The Bill to grant Scotland an Assembly was firstly, made to be

subject to a referendum, and then a requirement was added that the Bill

would become effective only if 40 per cent of the total Scottish

electorate supported it in the referendum. Labour and Conservative

opponents combined to fight for a 'No' vote in the referendum, and as time

dragged on the Scottish voters became increasingly bored with the whole

business. In any case the Labour government was becoming increasingly

unpopular, and the Bill suffered in popularity as a result. When the

referendum was eventually held in March 1979 it was supported by a

majority, but not by 40 per cent of the electorate.

Prime Minister Callaghan was caught between

the SNP members, whose votes were necessary for the survival of his

government, and a number of his own members who refused to allow the

Scotland Act to be accepted. The Nationalists then threatened that unless

the government would see the Bill through the Commons they would support a

vote of no confidence in Callaghan. Just as in 1707 an attempt at

political blackmail went wrong, so now in 1979 the SNP, acting on the most

righteous principle, voted with the Conservatives, and the Labour

government fell.

Douglas Crawford, George

Reid, Gordon Wilson, Douglas Henderson, Winifred Ewing, Donald Stewart,

Margaret Bain, Hamish Watt, Ian MacCormick, Andrew Welsh and George

Thomson, the eleven SNP MPs elected in 1974. (Photo: Gordon Wright)

The Conservatives won the General Election

which followed, and their further victories in 1983, 1987 and 1992 gave

them a prolonged period in office, enabling them to carry through a

programme which changed many aspects of British society profoundly. By the

time the Labour government ended, the economy of Britain was seen as

unsatisfactory. Productivity was poor, inflation was running at an

alarmingly high rate and the Labour party seemed unable to call upon

either loyalty or discipline which might change matters for the better.

Conservative supporters were increasingly

ready to argue that the consensus between the major parties, based on a

desire to compensate people for the suffering of the depression and the

hardships of war, should now end, because new economic policies were

required. The new thinking blamed Britain's economic ills upon the

structure of industry and utilities, much of it nationalised and

influenced by powerful Trade Unions, whose leaders resisted change in

working practices and rejected restraint of wages. Perceived excesses by

the unions and also by Labour-controlled municipalities played into the

hands of the Conservatives, who enjoyed popular support in the quarrel

which they proceeded to pick with those strongholds of Labour support.

A programme of legislation broke the power

of the unions by curbing the power of their leaders to embark upon strike

action, and government power to regulate the income of municipalities

steadily reduced the ability of local councils to devise and pursue

policies which were at odds with the wishes and purposes of central

government. With unions subdued and councils restricted, the government

was better able to pursue its wish to cut public spending and then cut

taxes, an achievement which they believed would win them continuing

electoral support.

Their belief was well justified as far as

voters in England were concerned. As the decade proceeded, much of England

enjoyed a surge of prosperity and the fortunes of the Conservative party

under Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher prospered accordingly.

However, where traditional, labour-intensive

industries persisted, and where Labour municipal power was correspondingly

strong, the response of the voters was very different. Scottish voters saw

very little affluence, but rather a very alarming decay in cities, with

rising unemployment and deepening poverty. In these circumstances voters

put their trust in the Labour party, the traditional protector of

industrial workers and their Trade Unions. This rallying round Labour was

encouraged by tough economic talking from the government which sounded

very like social indifference and which made the governing party and in

particular its leader, profoundly unpopular.

Though a majority of Scottish voters had

turned in their distress to Labour, there was very little Labour could do

as an Opposition. Before they could effectively bring help they would have

to become the Government, and that meant winning a majority of seats in

Britain as a whole. This prospect was remote after the humiliating and

disastrous defeats suffered in 1983 and 1987, and there developed a

growing support for the belief that instead of waiting for England to turn

to Labour, it would bring quicker rescue for Scots, if they were to claim

the right to self-government. If Scotland were to be self-governing then

Labour, as things stood, would be entitled to govern. Some Scottish Labour

MPs and many activists, suggested claiming the power but their hopes were

quickly crushed by the Labour leadership. The party was Unionist on

principle and its objective at elections was to win power in Britain.

Also, in terms of practical policies, if Labour were to win a positive

majority in the House of Commons, they would require the election of the

MPs which Scotland and Wales could be expected to provide. So, to keep

alive the hope of some day governing Britain, Labour had to deny its loyal

Scots their opportunity to escape from Conservative policies.

While Unionists resignedly accepted the

fact that Scots were governed by a party which they had clearly and

perseveringly rejected, Nationalists tried to make capital out of the

perceived injustice. The SNP had paid a bitter price for their purity of

principle in 1979, returning only two of their eleven members - Donald

Stewart in the Western Isles and Gordon Wilson in Dundee East. In 1983

they held only these two, while in 1987, following Mr Stewart's

retirement, they lost these two, winning three others by way of

compensation.

The SNP was not alone in seeking to bring

greater fairness to Scottish policies. After 1979 there had been created a

'Campaign for a Scottish Assembly', formed by supporters of Home Rule who,

for one reason or another, could not bring themselves to support the SNP.

This Campaign had drifted along, arousing no very great interest, but

after the 1987 defeat, and consequent restlessness in Labour's ranks,

there was more support on hand from Labour for the Campaign. Thus

enlivened, the Campaign drew upon past precedents and invited all parties,

municipalities, public bodies and organisations - trade unions and

churches for instance - to send representatives to a Constitutional

Convention. The intention was that suggestions for the better government

of Scotland could be put forward and discussed and an agreed set of

proposals might then be presented to the government for consideration.

Beginning at a somewhat leisurely pace, the

proceedings of the Convention speeded up after the 1988 by-election

victory in Govan, won by Jim Sillars for the SNP. After the consequent

surge of interest in the issue of Scotland's constitutional future, the

Convention extended renewed invitations to join in its work. The

Conservatives, denying the need for any such body, refused. The Labour and

Liberal parties were already present in strength, and co-operating in

control. The SNP at first sent representatives with considerable

misgivings and in the face of much opposition from its members. These

members still smarted from the betrayal, as they saw it, which had been

their lot in 1979 when Labour dissidents had effectively destroyed the

devolution plan. They now resented Labour's domination of the Convention;

they distrusted Labour's good faith, and they doubted the ability of

Labour's leadership to impose obedience upon those who might repeat the

sabotage of 1979. When they found that their beliefs and suggested options

would not be accepted for possible adoption by the Convention they then

withdrew their representatives.

For doing so they were subjected for the

next few years to a barrage of criticism from journalists and academics

who were sufficiently remote from practical politics to have an innocent

belief in the obtainability and virtue of an agreed consensus. In the

meantime the leading personalities of the Convention, and of the Labour

and Liberal parties all argued that their proposals were best because they

alone would save the Union from destruction. It seemed odd that the SNP

should be attacked for its refusal to support the very institution which

it sought to terminate.

In the absence of their opponents at either

extreme, the Labour and Liberal coalition produced a Home Rule scheme

which would give a Scottish Parliament a measure of power, excluding

international relations, defence and the fundamentals of economic policy.

Opinion polls suggested that this plan would enjoy the support of a

majority in Scotland, outstripping the support for independence or for no

change. The Labour party committed itself to legislation in the first year

of a new Parliament if the next General Election should place them in

power.

All this activity meant that the

constitutional issue would be high on the list of topics around which the

election campaign would revolve, and indeed the campaigning had already

begun by 1995 even though the election might be two years away. The SNP

especially felt the need to liven things up, fearing no doubt that too

much tranquillity would benefit either the government or the Convention

parties, with their programme packaged and ready, and appearing to be

widely acceptable even if not ecstatically received. Their pugnacity was

rewarded by a good performance in regional elections, as also in the

elections to the European Parliament. There Winifred Ewing had been

re-elected to represent the Highlands and Islands, and she was now joined

by Allan McArtney who had enjoyed a handsome victory by courtesy of the

voters of North-East Scotland. These encouragements were further enhanced

by a by-election victory gained by Roseanna Cunningham in Perth and

Kinross.

All parties now awaited the date and

outcome of the General Election which had to happen before April 1997. All

had their hopes. The Conservatives, though enduring some dreadful opinion

polls and a succession of by-election defeats, would know that the longer

they could postpone the election the better would be their chance of

recovery. The Liberals would be expected to hold what they had, and Labour

were expected to win, having shed old principles like nationalisation and

some of their more electorally unhelpful factions.

As for the SNP, they would have to wait

upon events. What would happen to them depended on what would happen to

others. If the Conservatives won again would there be this time a

substantial shift in the Labour ranks towards independence because only

escape from England would offer a realistic prospect of escape from

Conservatism?

If Labour won, but failed to carry out its

pledge to introduce a Scottish Parliament, would Scottish voters rise in

wrath and defect to the SNP; or would they, as in 1979, 1983, 1987 and

1992, just grin and bear it and try again in another few years? And, if

Labour won and did bring into being a Scottish Parliament, however

inadequate, would the voters then feel prompted to move further along the

road to Independence - the 'slippery slope' as Unionists called it. Or

would they instead relax to enjoy their gain and their new-found

recognition, consigning the SNP and its insistent protest to years of

oblivion? All possibilities existed.

One thing had not changed. Scots had to

give their answer to the essential questions - 'Do you believe that a

Scottish nation exists? and, if so, do you wish it to have a political

state of its own?' Existence without such a political identity had

continued from 1707 until the last few years of the twentieth century.

That continued existence, not in a political state, but purely in the

hearts and minds of the people, was almost incredible, but after three

miraculous centuries Scotland may go under at long last.

The economic indications of 1910 are

appearing again and Scots face these symptoms of decline with their

confidence weakened by almost a further century of self-doubt and

self-ridicule; their struggle to preserve an identity denounced, by

politicians and other moulders of opinion, as folly and anachronism. How

long Scots can be expected to maintain their self-awareness under such

pressures and in the face of such hostility, must be open to question. The

race is on between political reform and its alternative, the final ending

of the 'auld sang'. |