|

A FEW months after the death

of John Brown, I felt impelled to go again into the land of darkness and

slavery, and make another effort to help the oppressed to freedom. This time

I decided to make Kentucky my field of labour. I consequently went to

Louisville, where I remained for a few days looking about for a suitable

locality for my work. I finally decided, to go down to Harrodsburg, in the

character of one in search of a farm. Securing a few letters from land

agents in Louisville, introducing rue as Mr. Hawkins, of Canada, I reached

Harrodsburg in due time. After a little enquiry, I learned that a Mr. B—,

five miles from that place, had a very desirable farm for sale. Securing a

conveyance, I was driven out to Mr. B—'s, who received me in a friendly

manner, when he learned that I was in search of a farm, and invited me to

remain with him while I was in the neighbourhood. I accepted his invitation,

and sent the conveyance back to Harrodsburg. Mr. B—'s family consisted of

himself, wife, and three small children. He was the owner of the farm on

which he lived, consisting of three hundred acres. He also owned eleven

slave men and women, and several slave children. He informed me that he had

concluded to sell his farm and stock, except the human chattels, and remove

to Tex During our frequent conversations upon the subject of land, stock,

climate, soil, etc., I seized every opportunity, especially if any of the

slaves were near, to allude to Canada in favourable terms. I did not fail to

observe -the quiet but deep interest evinced by the slaves in our

conversations. On the third day of my visit, negotiations about the farm

were approaching—what Mr. B---- considered—a favourable conclusion, when he

casually informed me that his title-deeds were in Frankfort, and that, if I

was in other respects pleased with the farm, he would go to Frankfort and

bring the deeds for my inspection. I expressed my satisfaction with the

farm, and told him I thought he had better bring the deeds that I might look

them over. On the following morning he left for Frankfort. Before leaving, I

asked him to allow one of the slaves to accompany me to the woods, while I

amused myself gunning. He replied that I might take any of them I pleased. I

selected a bright, intelligent looking mulatto, whom I had frequently

noticed listening most attentively to my conversation with his master. When

we reached the woods, he begged and implored me to buy him and take him to

Canada.

A WIFE TORN FROM HER HUSBAND

AND SOLD.

He told me that his master

had sold his wife to whom he had been married only a month, to a

hotel-keeper in Covington, he spoke of his deep love for her; that his

master was going to take him to Texas, and that he should never see her

again. The tears rolled down the poor fellow's cheeks in streams. I told him

to cheer up that I would do my best to liberate him. I then confided to him

the object that brought me there; and told him that if liberty was precious

to him he must prepare to make great efforts and sacrifices for it. I

explained to him that if he could reach Cincinnati, Ohio, he would be safe

from his pursuers, and that he would be sheltered and protected until he

reached Canada. I then gave him the address of a friend in Cincinnati on

whom he could rely for protection, and also furnished him with some money, a

pistol, and pocket-compass for the journey to the Ohio. When he took the

pistol in his hand, I charged him not to use it except to prevent his

capture. He grasped the pistol like a vice, and said, "Massa, I'll get to

Cincinnati, if I am not killed." I then asked him if any of the other slaves

were capable of undertaking the journey. For a moment he was silent,

thinking, then he replied, "No, niassa; they are bad figgers; don't you

trust dem." I advised him to work on faithfully until Saturday night—it was

now Wednesday—and to make every preparation to leave at midnight on that

day, and to travel by night only. I told him I should go direct to Covington

on Friday, and would endeavour to liberate his wife ; that, if I succeeded,

he would find her at the house of the same friend in Cincinnati, whose

address I had given him. I advised him to carry with him as much food as

possible, so as to avoid exposure while on his journey. Poor Peter was

nearly wild with his prospects; so much so, indeed, that I urged him to

repress his feelings, for fear his conduct would be noticed by his mistress,

who had imbibed a particular dislike to Peter since his separation from his

wife. Mrs. B— told me he was a wicked nigger; that ever since Mr. B— had

sold the gal Peter had looked gloomy and revengeful; that she hated him.

Mrs. B— could not understand that Peter had any right not even the right to

sorrow, when his wife was torn from him and sold to a stranger.

On Thursday, Mr. B— returned.

He had been unsuccessful in obtaining the deeds, and told me that his

lawyers in Louisville, were willing I should have every facility to examine

them in their office, if I pleased; but, as they held a small mortgage on

the property, they were unwilling to permit the deeds to go out of their

possession. This was very satisfactory, and afforded me an opportunity to

get away without creating suspicion. During the night, previous to my

departure, I obtained an interview with Peter, and reiterated my injunctions

to be brave, cautious, and persevering, while on the journey, and again

impressed upon his memory my instructions. Poor fellow! his eyes filled with

tears when I told him I was going direct to Covington next day, and should

try and free his wife. When I bid him good-bye, he frantically kissed my

hand, saying, "Tell Polly I'll be dere, sure. Tell her to wait for me."

Oh! what a vile, wicked

institution was that which could make merchandise of such a man as stood

before me! Yet, monstrous and cruel as it was, it had its apologists and

abettors in the North ; while from every pulpit in the Slave States went

forth the declaration, that "slavery was a wise and beneficent institution,

devised by God for the protection of an inferior race."

On Friday morning I left,

ostensibly for Louisville, but went to Covington, which place I reached on

the following day. I had no difficulty in finding the hotel, having got the

name of Polly's owner from Peter. It was a poorly kept hostelry; the

proprietor evidently had no knowledge of hotel-keeping. I however took

quarters with him, and found him a very communicative man. He informed me he

had been a farmer until within a year past, but finding that farming on a

small scale was unprofitable, he had sold out, and bought this hotel. He was

the owner of two negroes, a man and woman; "the gal was likely, but mighty

spunky." He had paid twelve hundred dollars for her to Mr. B-, near

Harrodsburg. He wanted her to "take up" with his negro boy, but she refused.

He had threatened to send her to New Orleans for sale, if she would not obey

him. He reckoned she would be glad to "take up" with him before long; a good

whipping generally brought them to their senses. He knew how to manage suck.

The gal would bring sixteen hundred or two thousand dollars in New Orleans,

because she was likely.

Before retiring that night, I

requested the landlord to send to my room some warm water for a bath. He

said he would send the girl UI) with it as soon as it was ready. In less

than half an hour, the water was placed in my room by a bright, intelligent,

straight-haired mulatto girl, apparently twenty years of age. As soon as she

entered the room, I directed her to close the door, and said in a whisper,

"Arc you Polly, from Harrodsburg?" She looked at me with a frightened look,

"Yes, massa, I is," she said. I told her I had seen her husband, Peter, and

that he was going to run away from his master on Sunday night ; that I had

friends in Cincinnati where he was going, who would secrete him until she

could join him, when they would both be sent to Canada. She stood like a

statue, while I was talking. I directed her to get ready to meet me on the

following night, at twelve o'clock, in front of the post office; that I

should leave the hotel in the morning and make preparations to have her

taken across the river to the Ohio shore. She was so much amazed that for a

moment she was unable to speak; at last she said, "Please, massa, tell me it

over again." I repeated my instructions as rapidly as possible for fear I

should be interrupted; and warned her against betraying herself by any

outward expression of her feelings. When I concluded, she said, "Oh, massa,

I'll pray to God for you—I'll be dere sure." She then left the room. Next

morning I delayed corning down to breakfast until after the regular

breakfast was over, hoping to obtain another opportunity of charging her

memory with the the instructions already given. I was fortunate—she served

the table. When I was leaving the table, I said to her, "Tonight at twelve

o'clock, sure." She replied in a whispers "God will help me, massa, I'll try

to." After breakfast, I went to Cincinnati and with the aid of friends, made

arrangements to cross to. Covington at eleven o'clock that night.

LIBERATION OF THE WIFE.

Before dark on Sunday

evening, I had completed all my arrangements. A short time before midnight,

I crossed the river in a small boat with two good assistants. Leaving them

in charge of th boat, I went up to the post office, which I reached a few

minutes before twelve. I waited patiently for nearly half an hour, when I

observed a dark object approaching rapidly at a distance of several hundred

yards from where I stood. As soon as I recognized the form, I went toward

her, and, telling her to follow me, I turned down a dark street, and went

toward the river. We had made but little progress before we were stopped by

a night watchman, who said, "Where arc you going ?" I replied by putting a

dollar in his hand and saying, it's all right. He became oblivious, and

passed on his beat, greatly to my, peace of mind. We soon reached the boat;

she crouched down in the bow, and we left the Kentucky shore.

CROSSING THE OHIO.

In a short time we were safe

across the river, and placing my charge in a cab which I had ready at the

shore, we drove rapidly up into the city within a few blocks of my friend's

residence. I then dismissed the cab, and we wended our way through several

streets, until I reached the rear entrance to the house of my friend. We

were admitted, and received the kind attention of our generous and

liberty-loving host, Poor Polly, who had never before been treated with such

kindness, said to me: "Massa, is I free now?" I told her she was now free

from her master; and that, as soon as her husband arrived, they both would

be sent to Cleveland, where I would meet them, and help them across to

Canada, where they would be as free as the whites. Bidding her and my noble

hearted friend good-by, I took the first train on Monday morning for

Cleveland. On my arrival there, I drove a few miles into the country to the

house of a friend of the cause, where I remained waiting for news of Peter's

arrival in Cincinnati. On Friday morning I received a letter informing me

that Peter had arrived safely, though his feet were torn and sore. The

meeting between husband and wife was described as most affecting. On Monday

evening following, I received another letter stating that freight car No.

705, had been hired to convey a box containing one "package of hardware,"

and one of "dry goods," to Cleveland. The letter also contained the key of

the car. The train containing this particular car was to leave Cincinnati on

Tuesday morning, and would reach Cleveland, sometime during the evening of

the same day. I had but a short time consequently to make preparations to

convey the fugitives across the lake.

A KENTUCKIAN IN SEARCH OF HIS

CHATTEL.

On Tuesday morning, my good

friend with whom I had been stopping, drove me into Cleveland. As we passed

the American House, I caught sight of my Kentucky host standing in front of

the hotel. He did not observe me, however, and we continued on our way to

the lake shore. I then sent my friend back to make the acquaintance of the

Kentuckian, and learn the object of his visit to Cleveland. After a long

search, I found a schooner loading for Port Stanley, Canada. The skipper

said they would be ready to sail on the following day if the wind was

favourable. I soon learned that the captain was a Freemason, and confided to

him my secret. The result was, his agreement to stow my freight away safely

as soon as they came on board, and carry them to Canada I then returned to a

locality agreed upon with my friend, whom I found waiting for me, and was

then driven to the country. On the way out, my friend informed me that he

had made the acquaintance of the Kentuckian, who felt very sore over the

loss of his slave ; but he did not express any suspicion of inc. He said he

was having posters printed, offering a reward of five hundred dollars for

the capture of the girl. Toward night, I again went into the city, and my

friend made enquiry at the freight office of the railroad, and ascertained

that the train containing car 705, would be in at 10 p.m. We then went to a

hotel near the depot, and remained until the train came. I found the car,

and my faithful friend brought his carriage as near as he could safely,

without attracting attention. I unlocked the door of the car, went in, and

closed the door after me. Listening carefully, I could not detect the

slightest signs of life in the car. I called in a low voice: "Peter." A

reply came at once : "Yes, massa, shall I open the box ?" The two poor

creatures were in a dry-goods box, sufficiently large to permit them to sit

upright. I helped them out of the box, and making sure that no stranger was

near, opened the, door of the car, and led them quickly to the carriage. We

then drove rapidly away to the boat, and secreted the fugitives in the

cabin. I then bid my friend farewell, as I had decided not to leave the two

faithful creatures until they were safe in Canada.

SAFE ARRIVAL OF MAN AND WIFE

IN CANADA.

After midnight the breeze

freshened up, and we made sail for the land of freedom. We had a rough and

tedious voyage, and did not reach Canada until near night on the following

day. When our little vessel was safely moored alongside the pier, I led my

two companions on shore, and told them they were now in a land where freedom

was guaranteed to all. And we kneeled together on the soil of Canada, and

thanked the Almighty Father for his aid and protection. Two happier beings I

never saw. Next day I took them to London, and obtained situations for both

Peter and his wife. I succeeded also in enlisting the kind interest of

several prominent persons in their behalf, to whom I related their

experience.

NET RESULTS.

The next three months I spent

in Canada visiting those refugees in whom I had taken a personal interest. I

found six in Chatham, two in London, four in Hamilton, two in Amherstburg,

and one iii Toronto—fifteen in all; while several others had gone from

Canada to New England.

It afforded me great

satisfaction to find them sober, industrious members of society. It has

often been remarked by both Canadians and visitors from the States, that the

negro refugees in Canada were superior specimens of their race. The

observation is true, for none but superior specimens could hope to reach

Canada. The difficulties and dangers of the route, and the fact that they

were often closely followed for weeks, not only by human foes, but by

bloodhounds as well, required the exercise of rare qualities of mind and

body. Their route would often lay through dismal swamps inhabited only by

wild animals and poisonous reptiles. Sometimes the distance between the land

of bondage and freedom was several hundreds of miles, every mile of which

had to be traversed on foot. It is, indeed, surprising that so large a

number of fugitives succeeded in reaching Canada, considering the obstacles

they had to contend with on their long and dangerous journey.

When I reflect upon the dangers that surrounded

me during that stormy period, I acknowledge my indebtedness to God for His

protection and support during my labours in behalf of the oppressed people

of the Southern States ; and, although the results of my efforts were

insignificant in comparison to what I hoped to accomplish when I began the

work in 1855, I still rejoice that I was enabled to do what little I (lid

for the poor and despised coloured people of the Slave States.

NUMBER OF REFUGEE NEGROES IN CANADA.

The number of refugee negroes living in Canada,

at the outbreak of the slaveholder's rebellion, was not far short of forty

thousand. Probably more than half of them were manumitted slaves who, in

consequence of unjust laws, were compelled to leave the States where they

were manumitted. Many of these negroes. settled in the Northern States, but

the greater portion of them came to Canada.

THE FUGITIVE SLAVE LAW.

When the Fugitive Slave Law was enacted in i85o,

it carried terror to every person of African blood, in the Free States.

Stung with hopeless despair, more than six thousand Christian men and women

fled from their homes, and sought refuge under the flag of Britain in

Canada. In the words of Charles Sumner: "The Free States became little

better than a huge outlying plantation, quivering under the lash of the

overseer; or rather they were a diversified hunting ground for the flying

bondman, resounding always with the 'halloo' of the huntsman. There seemed

to be no rest. The chase was hardly finished at Boston, before it broke out

at Philadelphia, Syracuse, or Buffalo, and then again raged furiously over

the prairies of the west. Not a case occurred which did not shock the

conscience of the country, and sting it with anger. The records of the time

attest the accuracy of this statement. Perhaps there is no instance in

history where human passion showed itself in grander forms of expression, or

where eloquence lent all her gifts more completely to the demands of

liberty, than the speech of Theodore Parker, (now dead and buried in a

foreign land), denouncing the capture of Thomas Simms at Boston, and

invoking the judgment of God and man upon the agents in this wickedness. The

great effort cannot be forgotten in the history of humanity. But every case

pleaded with an eloquence of its own, until at last one of those tragedies

occurred which darken the heavens, and cry out with a voice that will be

heard. It was the voice of a mother standing over her murdered child.

Margaret Garner had escaped from slavery with three children, but she was

overtaken at Cincinnati. Unwilling to see her offspring returned to the

shambles of the South, this unhappy person, described in the testimony as 'a

womanly, amiable, affectionate mother,' determined to save them in the only

way within her power. With a butcher knife, coolly and deliberately, she

took the life of one of the children, described as 'almost white, and a

little girl of rare beauty,' and attempted, without success, to take the

life of the other two. To the preacher who interrogated her, she exclaimed

'The child is my own, given me of God to do the best a mother could in its

behalf. I have done the best I could; I would have done more and better for

the rest ; I knew it was better for them to go home to God than back to

slavery.' But she was restrained in her purpose. The Fugitive Slave Act

triumphed, and after the determination of sundry questions of jurisdiction,

this devoted historic mother, with the two children that remained to her,

and the dead body of the little one just emancipated, was escorted by a

national guard of armed men to the doom of slavery. But her case did not end

with this revolting sacrifice. So long as the human heart is moved by human

suffering, the story of this mother will be read with alternate anger and

grief, while it is studied as a perpetual witness to the slaveholding

tyranny which then ruled the Republic with execrable exactions, destined at

last to break out in war, as the sacrifice of Virginia by her father is a

perpetual witness to the decemviral tyranny which ruled Rome. But liberty is

always priceless. There are other instances less known in which kindred

wrong has been done. Every case was a tragedy— under the forms of law. Worse

than poisoned bowl or dagger was the certificate of a United States

commissioner—who was allowed, without interruption, to continue his dreadful

trade." THE PRESIDENTIAL

ELECTION OF 1860.

During no previous presidential election, (except that of 1856, when Fremont

and Buchanan were the candidates), was there so much excitement on the

slavery question as that of 1860, when Lincoln, Breckinridge, Bell, and

Douglas were the candidates.

To enable my readers to form a correct idea as

to the political positions occupied by the different candidates towards the

institution of slavery, I give below the "slavery plank of each platform" on

which the presidential candidates went before the people for their

suffrages:— REPUBLICAN

NATIONAL (LINCOLN) PLATFORM.

ADOPTED AT CHICAGO, 1860.

Resolved, That we, the delegated representatives

of the Republican electors of the United States, in Convention assembled, in

discharge of the duty we owe to our constituents and our country, unite in

the following declarations :-

1. That the history of the nation, during the

last four years, has fully established the propriety and necessity of the

organization and perpetuation of the Republican party, and that the causes

which called it into existence are permanent in their nature, and now, more

than ever before, demand its peaceful and constitutional triumph.

2. That the maintenance of the principles

promulgated in the Declaration of Independence and embodied in the Federal

Constitution, "That all men are created equal; that they are endowed by

their creator with certain inalienable rights; that among these are life,

liberty, and the pursuit of happiness that to secure these rights,

governments are instituted among men, deriving their just powers from the

consent of the governed," is essential to the preservation of our Republican

institutions; and that the Federal Constitution, the Rights of the States,

and the Union of the States, must and shall be preserved.

7. That the new dogma, that the Constitution, of

its own force, carries Slavery into any or all of the Territories of the

United States, is a dangerous political heresy, at variance with the

explicit provisions of that instrument itself, with contemporaneous

exposition, and with legislative and judicial precedent; is revolutionary in

its tendency, and subversive of the peace and harmony of the country.

8. That the normal condition of all the

territory of the United States is that of freedom; That as our Republican

fathers, when they had abolished Slavery in all our national territory,

ordained that "no person should be deprived of life, liberty, or property,

without due process of law," it becomes our duty, by legislation, whenever

such legislation is necessary, to maintion this provision of the

Constitution against all attempts to violate it; and we deny the authority

of Congress, of a territorial legislature, or of any individuals, to give

legal existence to Slavery in any Territory of the United States.

0. That we brand the recent re-opening of the

African slave-trade, under the cover of our national flag, aided by

perversions of judicial power, as a crime against humanity and a burning

shame to our country and age; and we call upon Conress to take prompt and

efficient measures for the total and final suppression of that execrable

traffic. NATIONAL

DEMOCRATIC (DOUGLAS) PLATFORM.

ADOPTED AT CHARLESTON AND BALTIMORE, 1860.

1. Resolved, That we, the Democracy of the

Union, in Convention assembled, hereby declare our affirmance of the follow.

ing resolutions :-

Resolved, That the enactments of State Legislatures to defeat the faithful

execution of the Fugitive Slave Law, are hostile in character, subversive of

the Constitution, and revolutionary in their effect.

Resolved, That it is in accordance with the true

interpretation of the Cincinnati Platform, that, during the existence of the

Territorial Governments, the measure of restriction, whatever it may be,

imposed by the Federal Constitution on the power of the Territorial

Legislature over the subject of the domestic relations, as the same has

been, or shall hereafter be, finally determined by the Supreme Court of the

United States, shall be respected by all good citizens, and enforced with

promptness and fidelity by every branch of the General Government.

NATIONAL DEMOCRATIC (BRECKINRIDGE) PLATFORM.

ADOPTED AT CHARLESTON AND BALTIMORE, 1860.

Resolved, That the Platform adopted by the

Democratic party at Cincinnati be affirmed, with the following explanatory

Resolutions:— 1. That

the Government of a Territory organized by an Act of Congress, is

provisional and temporary; and during its existence, all citizens of the

United States have an equal right to settle with their property in the

Territory, without their rights, either of person or property, being

destroyed or impaired by Congressional or Territorial legislation.

2. That it is the duty of the Federal

Government, in all its departments, to protect, when necessary, the rights

of persons and property in the Territories, and wherever else its

constitutional authority extends.

3. That when the settlers in a Territory having

an adequate population, form a State Constitution, in pursuance of law, the

right of sovereignity commences, and, being consummated by admission into

the Union, they stand on an equal footin with the people of other States;

and the State thus organize ought to be admitted into the Federal Union,

whether its Constitution prohibits or recognizes the institution of Slavery.

5. That the enactments of State Legislatures to

defeat the faithful execution of the Fugitive Slave Law are hostile in

character, subversive of the Constitution, and revolutionary in their

effect. CONSTITUTIONAL

UNION (BELL-EVERETT) PLATFORM.

ADOPTED AT BALTIMORE, 1860.

Whereas, Experience has demonstrated that

Platforms adopted by the partisan conventions of the country have had the

effect to mislead and deceive the people, and at the same time to widen the

political divisions of the country, by the creation and encouragement of

geographical and sectional parties; therefore, Re-solved, That it is both

the part of patriotism and of duty to recognize no political principle other

than THE CONSTITUTION OF THE COUNTRY, THE UNION OF THE STATES, AND THE

ENFORCEMENT OF THE LAWS, and that as representatives of the Constitutional

Union men of the country in National Convention assembled, we hereby pledge

ourselves to obtain, protect, and defend, separately and unitedly, these

great principles of public liberty and national safety, against all enemies

at home and abroad, believing that thereby peace may once more be restored

to the country, the rights of the People and of the States re-established,

and the Government again placed in that condition, of justice, fraternity,

and equality, which under the example and Constitution of our fathers, has

solemnly bound every citizen of the United States to maintain a more perfect

union, establish justice, insure domestic tranquility, provide for the

common defence, promote the general welfare, and secure the blessings of

liberty to ourselves and our posterity.

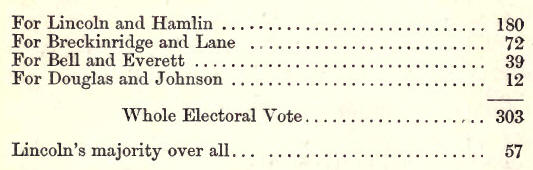

ELECTORAL VOTE, PRESIDENTAL ELECTION OF 1860.

When enough returns from the election had been

received to render it certain that Abraham Lincoln would be the next

President, public meetings were held in the city of Charleston and in other

places in the State of South Carolina, at which resolutions were adopted in

favor of the Secession of the State from the Union.

DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE OF SOUTH CAROLINA.

DONE IN CONVENTION, DECEMBER 24, 1860.

The State of South Carolina, having determined

to resume her separate and equal place among nations, deems it due to

herself, to the remaining United States of America, and to the nations of

the world, that she should declare the causes which have led to this act.

We affirm that these ends for which this

government was instituted have been defeated, and the government itself has

been made destructive of them by the action of the non-slave. holding

States. These States have assumed the right of deciding upon the propriety

of our domestic institutions, and have denied the rights of property

established in fifteen of the States and recognized by the Constitution;

they have denounced as sinful the institution of slavery; they have

permitted the open establishment among them of societies whose avowed object

is to disturb the peace and to eloin the property of the citizens of other

States. They have encouraged and assisted thousands of our slaves to leave

their homes, and those who remain have been incited by emissaries to servile

insurrection. Sectional

interest and animosity will deepen the irritation, and all hope of remedy is

rendered vain by the fact that public opinion at the north has invested a

great political error with the sanctions of a more erroneous religious

belief. We, therefore,

the people of South Carolina, appealing to the Supreme Judge of the world

for the rectitude of our intentions, have solemnly declared that the union

heretofore existing between this State and the other States of North America

is dissolved, and that the State of South Carolina has resumed her position

among the nations of the world as a free, sovereign, and independent State.

And for the support of this declaration, with a

firm reliance on the protection of Divine Providence, we mutually pledge to

each other our lives, our fortunes, and our sacred honor.

On the same day the remaining representatives in

Congress from South Carolina vacated their seats and returned home; and thus

began the slaveholders' rebellion. |