|

AT Springfield, Mass., the

train stopped sufficiently long to enable the passengers to get supper. As I

took my seat at the table I observed an elderly gentleman looking very

earnestly at me. I felt sure I had seen him before somewhere; but where and

when I had quite forgotten. At length he recognized me, and taking a seat

near me said, in a whisper, "How is the hardware business?" The moment he

spoke I remembered the voice, and recalled my old Cleveland acquaintance,

Capt. John Brown, of Kansas.

SECOND INTERVIEW WITH JOHN

BROWN.

He was much changed in

appearance, looking older and more careworn ; his face was covered with a

long beard, nearly white; his dress was plain, but good and scrupulously

clean. There was no change in his voice or eye, both were indicative of

strength, honesty, and tenacity of purpose. Learning that I was on my way to

Boston, whither he was going on the following day, he urged me to remain in

Springfield over night, and accompany him to Boston. After supper we retired

to a private parlour, and he requested me to tell him all about my trip

through Mississippi and Alabama. He remarked that our mutual friend, of

Northern New York, had told him that when he last heard from me, I was in

Selma. He listened to the recital of my narrative, from the time I left New

Orleans until my arrest at Columbus, with intense earnestness, without

speaking, until I described my arrest and imprisonment, then his countenance

changed, his eyes flashed, he paced the room in fiery wrath. I never

witnessed a more intense manifestation of indignation, and scorn. Coming up

to me, he took my wrists in his hands and said, "God alone brought you out

of that hell; and these wrists have been ironed, and you have been cast in

prison for doing your duty. I vow, henceforth, that I will not rest in my

labour until I have discharged my whole duty toward God, and toward my

brother in bondage." When he ceased speaking he sat down and buried his face

in his hands, in which position he sat for several minutes, as if overcome

by his feelings. At length, arousing himself, he asked me to continue my

narrative, to which he listened earnestly during its recital. He said, "The

Lord has permitted you to do a work that falls to the lot of but few";

taking a small Bible or Testament from his pocket, he said, "The good book

says, 'Whatsoever ye would that men should do to you, do ye even so to

them'; it teaches us further, to 'remember them in bonds, as bound with

them." He continued, "I have devoted the last twenty years of my life to

preparation for the work which, I believe, God has given me to do." He then

gave rue some details of a campaign which he was then actually preparing

for, and which he said had occupied his mind for years. He intended to

establish himself in the mountains of Virginia with a small body of picked

men —men in whom he could trust, and who feared God. He felt confident that

the negroes would flock to him in large numbers, and that the slaveholders

would soon be glad to let the oppressed go free; that the dread of a negro

insurrection would produce fear and trembling in all the Slave States; that

the presence in the mountains of an armed body of Liberators would produce a

general insurrection among the slaves, which would end in their freedom. He

said he had about twenty-two Kansas men undergoing a course of military

instruction; these men would form a nucleous, around which he would soon

gather a force sufficiently large and effective to strike terror throughout

the Slave States. His present difficulty was, a deficiency of ready money;

he had been promised support—to help the cause of freedom—which was not

forth- corning, now that he was preparing to carry the war into the South

His friends were disinclined to aid offensive operations.

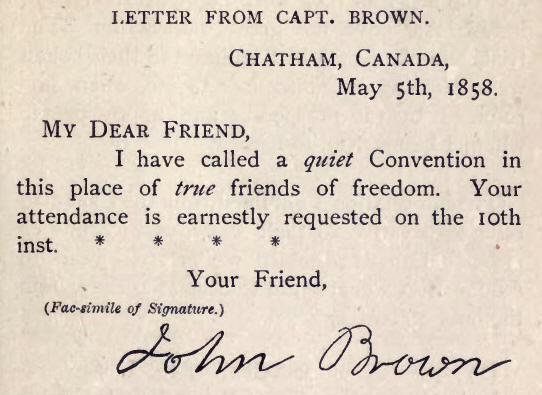

During this interview, he

informed me that he intended to call a Convention of the friends of the

cause at Chatham, Canada, in a few weeks, for the purpose of effecting an

organization composed of men who were willing to aid him in his purpose of

invading the Slave States. He said he had rifles and ammunition sufficient

to equip two hundred men; that he had made a contract for a large number of

pikes, with which he intended to arm the negroes; that the object of his

present trip to the East was, to raise funds to keep this contract, and

perfect his arrangements for an attack upon the Slave States in the

following September or October.

Captain Brown accompanied me,

on the following day, to Boston. During our journey, he informed me that he

required a thousand dollars at least to complete his preparations; that he

needed money at once to enable him to keep a contract for arms with some

manufacturer in Connecticut. He also needed money to bring his men from Iowa

to Canada. On our arrival in Boston, I went to the house of a friend, and

Capt. Brown took quarters at a hotel. I saw him every day while he remained

in Boston ; and regretted to learn that he met with but little success in

obtaining money. It appeared that those friends of the cause of freedom, who

had an inkling of his project, were not disposed to advance money for

warlike purposes, except such as were for the defence of free territory. He

finally did succeed in raising about five hundred dollars. An impression

prevailed, in the minds of many sincere friends of freedom, that the

persecution of himself and family by the pro-slavery men of Kansas had so

exasperated him that he would engage in some enterprize which would result

in the destruction of himself and followers. I am persuaded that these

impressions were groundless. I never heard him express any feeling of

personal resentment towards the slaveholders. He at all times, while in my

company, appeared to be controlled by a fixed, earnest, and unalterable

determination to do what he considered to be his duty, as an agent in the

hands of the Almighty, to give freedom to the slaves. That idea, and that

alone, appeared to me to control his thoughts and actions.

On the morning of his

departure from Boston, I accompanied him to the depot, and bid him farewell.

(I never again saw the brave old captain in life.) A few days afterwards,

however, I received the following:-

In consequence of my absence

from Boston, I did not receive the above letter until the 1301 of May—three

days after the time appointed for the meeting of the Convention.

REFUGEES IN CANADA.

During the summer of 1858 I

visited Canada, and had great pleasure in meeting several of those who had,

under my auspices, escaped from the land of bondage. In a barber shop, in

Hamilton, I was welcomed by a man who had escaped from Augusta, and who

kept, as a souvenir of my friendship, a dirk knife I had given him on the

night he started for Canada. The meeting with so many of my former pupils,

and the fact that they were happy, thriving, and industrious, gave me great

satisfaction. The trials and dangers I had endured in their behalf were

pleasing reminiscences to me, when surrounded by the prosperous and happy

people whom I had striven to benefit.

The information I obtained

from the Canadian refugees, relative to their experiences while en route to

Canada, enabled me in after years to render most valuable aid to other

fugitives from the land of bondage.

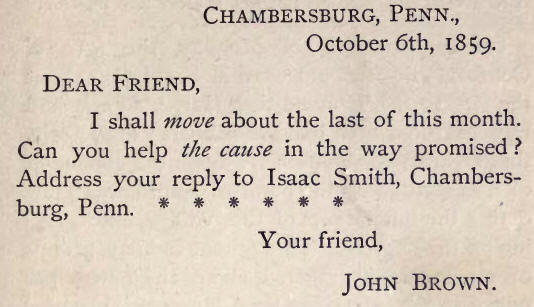

On the 9th of October, 1859,

I was surprised to receive the following letter from Captain Brown,

announcing his determination to make an attack on the slave States in the

course of a few weeks. The letter reads as follows:-

IN RICHMOND.

Soon after the reception of

the above letter I left for Richmond, Virginia, much against the wishes of

my friends. I had promised Captain Brown, during our interview at

Springfield, Mass., that when he was ready to make his attack on the Slave

States, I would go to Richmond and await the result. In case he should be

successful in his attack, I would be in a position to watch the course of

events, and enlighten the slaves as to his purposes. It might also be

possible for me to aid the cause in other respects. On my arrival in

Richmond, I went to the house of an old friend, with whom I had stopped

during my previous raid on the chattels of Virginia's slaveholders.

CAPTAIN BROWN ATTACKS HARPER'S

FERRY

On the morning of Monday, the

17th of October, wild rumours were in circulation about the streets of

Richmond that Harper's Ferry had been captured by a band of robbers; and,

again, that an army of abolitionists, under the command of a desperado by

the name of Smith, was murdering the inhabitants of that village, and

carrying off the negroes. Throughout the day, groups of excited men gathered

about the newspaper offices to hear the news from Harper's Ferry.

On the following morning

(Tuesday) an official report was received, which stated the fact that a

small force of abolitionists, under old Ossawatomie Brown, had taken

possession of the U. S. building at the Ferry, and had entrenched

themselves. I met an aged negro in the street, who seemed completely

bewildered about the excitement and military preparations going on around

him. As I approached him, he lifted his hat and said: "Please massa, what's

the matter? What's the soldiers called out for?" I told him a band of

abolitionists had seized Harper's Ferry, and liberated many of the slaves of

that section; that they intended to free all the slaves in the South, if

they could. "Can dey do it, massa?" he asked, while his countenance

brightened up. I replied by asking him, if he wished to be free? He said: "O

yes, massa; I'se prayed for dat dese forty years. My two boys are way off in

Canada. Do you know whar dat is, massa?" I told him I was a Canadian, which

seemed to give him a great surprise. He said his two boys had run away from

their master, because he threatened to take them to New Orleans for sale.

That John Brown had struck a

blow that resounded throughout the Slave States was evident, from the number

of telegraph des- patches from all the Slave States, offering aid to crush

the invasion.

DEFEAT OF CAPTAIN BROWN.

The people of Richmond were

frantic with rage at this daring interference with their cherished

institution, which gave them the right to buy, beat, \work, and sell their

fellow men. Crowds of rough, excited men, filled with whiskey and

wickedness, stood for hours together in front of the offices of the Despatch

and Enquirer, listening to the reports as they were announced from within.

When the news of Brown's defeat and capture, and the destruction of his

little army, was read from the window of the Despatch office, the vast

crowds set up a demoniac yell of delight, which to me sounded like a death

knell to all my hopes for the freedom of the enslaved. As the excitement was

hourly increasing, and threats made to search the city for abolitionists, I

saw that nothing could be gained by remaining in Richmond. I left for

Washington, nearly crushed in spirit at the destruction of Captain Brown and

his noble little band. On the train were Southerners from many of the Slave

States, who expressed their views of Northern abolitionists in the most

emphatic slave-driving language. The excitement was intense, every stranger,

especially if he looked like a Northerner, was closely watched, and in some

instances subjected to inquisition.

DOUGH-FACED NORTHERNERS.

The attitude of many of the

leading Northern politicians and so-called statesmen, in Washington, was

actually disgusting. These weak-kneed and craven creatures were profuse in

their apologies for Brown's assault, and hastened to divest themselves of

what little manhood they possessed, when in the presence of the braggarts

and women-whippers of the South. "What can we do to conciliate the Slave

States?" was the leading question of the day. Such men as Crittenden, and

Douglas, were ready to compromise with the slaveholders even at the

sacrifice of their avowed principles. While Toombs, Davis, Mason, Slidell,

and the rest of the slave- driving crew, haughtily demanded further

guarantees for the protection of their "institution ;" and had it not been

for the stand taken by the people of the Northern States at that time, their

political leaders would have bound the North, hand and foot, to do the

bidding of the slaveholders. But on that occasion, as well as all others

where the principles of freedom have been involved, the people of the United

States were found worthy descendants of their revolutionary sires.

EFFECTS OF JOHN BROWN'S

ATTACK.

The blow struck at Harper's

Ferry, which the Democratic leaders affected to ridicule, had startled the

slaveholders from their dreams of security, and sent fear and trembling into

every home in the Slave States. On every plantation the echoes from Harper's

Ferry were heard. The poor terrified slave, as he laid down at night, weary

from his enforced labours, offered up a prayer to God for the safety of the

grand old captain, who was a prisoner in the hands of merciless enemies, who

were thirsting for his blood.

BRAVERY OF CAPTAIN BROWN.

How bravely John Brown bore

himself while in the presence of the human wolves that surrounded him, as he

lay mangled and torn in front of the engine-house at Harper's Ferry! Mason,

of Virginia, and that Northern renegade, Vallandigharn, interrogated the

apparently dying man, trying artfully, but in vain, to get him to implicate

leading Northern men. In the history of modern times there is not recorded

another instance of such rare heroic valour as John Brown displayed in the

presence of Governor Wise, of Virginia. How contemptible are Mason, Wise,

and Vallandigham, when compared with the wounded old soldier, as he lay

weltering in his blood, and near him his two sons, Oliver and Watson, cold

in death. Mason and Vallandigham died with the stain of treason on their

heads, while Governor Wise, who signed Brown's death warrant, still lives,

despised and abhorred.

To superficial observers,

Brown's attack on Virginia with so small a force, looked like the act of a

madman; but those who knew John Brown, and the men under his command, are

satisfied that if he had carried out his original plans, and retreated with

his force to the mountains, after he had captured the arms in the arsenal,

he could have defeated and baffled any force sent against him. The slaves

would have flocked to his standard in thousands, and the slaveholders would

have trembled with fear for the safety of their families.

JOHN BROWN VICTORIOUS.

John Brown in prison,

surrounded by his captors, won greater victories than if he had conquered

the South by force of arms. His courage, truthfulness, humanity, and

self-sacrificing devotion to the cause of the poor downtrodden slaves,

shamed the cowardly, weak-kneed, and truculent Northern politicians into

opposition to the haughty demands of the despots of the South.

"HIS SOUL IS MARCHING ON."

Virginia, in her pride and

strength, judicially murdered John Brown. But the day is not far distant

when the freedmen and freemen of the South will erect a monument on the spot

where his gallows once stood, to perpetuate to all coming generations the

noble self-sacrifice of that brave Christian martyr. And when the Southern

statesmen who shouted for his execution are mouldering in the silent dust,

forgotten or unpleasantly remembered, the memory of John Brown will grow

brighter and brighter through all coming ages.

JOHN BROWN'S MARTYRDOM.

December the 2nd, was the day

appointed for the execution of Capt. Brown. I determined to make an effort

to see him once more if possible. Taking the cars at Baltimore, on Nov.

26th, I went to Harper's Ferry and applied to the military officer in

command for permission to go to Charleston. He, enquired what object I had

in view in wishing to go there at that time, while so much excitement

existed. I replied, that I had a desire to see John Brown once more before

his death. Without replying to me, he called an officer in the room and

directed him to place me in close confinement until the train for Baltimore

came, and then to place me on board, and command the conductor to take me to

Baltimore. Then, raising his voice, he said, "Captain, if he (myself)

returns to Harper's Ferry, shoot him at once." I was placed under guard

until the train came in, when, in despite of my protests, I was taken to

Baltimore. Determined to make one more attempt, I went to Richmond to try

and obtain a pass from the Governor. After much difficulty I obtained an

INTERVIEW WITH GOVERNOR WISE.

I told the Governor that I

had a strong desire to see John Brown before his execution; that I had some

acquaintance with him, and had formed a very high estimate of him as a man.

I asked him to allow me to go to Charlestown (under surveillance if he

pleased), and bid the old Captain "Good bye." The Governor made many

inquiries as to my relation to Brown, and whether I justified his attack on

Virginia. I replied candidly, stating that I had from childhood been an

ardent admirer of Washington, Jefferson, and Madison, and that all these

great and good men deplored the existence of slavery in the Republic. That

my admiration and friendship for John Brown was owing to his holding similar

views, and his earnest desire to abolish the evil. The Governor looked at me

with amazement, and for a moment made no reply. At length he straightened

himself up, and, assuming a dignified look, said, "My family motto is, 'saere

aside.' I am wise enough to understand your object in wishing to go to

Charlestown, and I dare you to go. If you attempt it, I will have you shot.

It is just such men as you who have urged Brown to make his crazy attack on

our constitutional rights and privileges. You shall not leave Richmond until

after the execution of Brown. I wish I could hang a dozen of your leading

abolitionists."

HE WOULD LIKE TO BAG GIDDINGS

AND GERRIT SMITH.

"If I could bag old Giddings

and Gerrit Smith, I would hang them without trial." The Governor was now

greatly excited, and, rising from his chair, he said, "No, sir you shall not

leave Richmond. You shall go to prison, and remain there until next Monday;

then you may go North, and slander the State which ought to have hanged

you." I quietly waited a moment before replying, and then remarked, that as

he refused me permission to see Capt. Brown, I would leave Virginia at once,

and thus save both him and the State any trouble or expense on my account. I

said this very quietly, while his keen eyes were riveted on me. In reply, he

said, "Did I not tell you that you should remain a prisoner here until

Monday?" I quietly said, "Yes, Governor, you certainly did; but I am sure

the executive of this great State is toowise to fear one unarmed man." For a

few moments he tapped the table with his fingers, without saying anything.

Then he came toward me, shaking his fore finger, and said: "Well, you may

go; and I would advise you to tell your Giddings, Greeleys, and Garrisons,

cowards that they are, to lead the next raid on Virginia themselves."

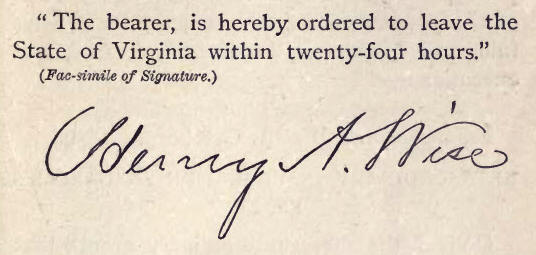

Fearing that obstacles might

be thrown in my way which would cause detention and trouble, I requested the

Governor to give me a permit to leave the State of Virginia. Without making

any reply, he picked up a blank card, and wrote as follows :-

This he handed me, saying,

"The sooner you go, the better for you: our people are greatly excited, and

you may regret this visit, if you stay another hour."

I returned to Philadelphia as

rapidly as possible, where I remained until the remains of Capt. Brown

arrived, en route for their final resting place at North Elba, in Northern

New York. Having taken my last look at the dead liberator, I returned to

Canada, where I remained until my preparations were completed for another

visit to the South.

EXTRACTS FROM THE PRESS OF

THAT PERIOD.

The following Extracts from

the Press of that period, will furnish my readers with a good index of the

popular feeling respecting John Brown's raid, and his defeat, imprisonment,

trial, and execution :-

From Harper's Weekly, October

29, 1859.

EXTRAORDINARY INSURRECTION AT

HARPER'S FERRY.

One of the most extraordinary

events that ever occurred in our history took place last week at Harper's

Ferry. We shall endeavour to give our readers a connected history of the

affair, which, at the present time, has been brought to a close.

THE FIRST ACTIVE MOVEMENT.

The first active movement in

the insurrection was made at about half-past ten o'clock on Sunday night.

William Williamson, the watchman at Harper's Ferry bridge, while walking

across toward the Maryland side, was seized by a number of men, who said he

was their prisoner, and must come with them. He recognized Brown and Cook

among the men, and knowing them, treated the matter as a joke, but enforcing

silence, they conducted him to the Armory, which he found already in their

possession. He was detained till after daylight, and then discharged. The

watchman who was to relieve Williamson at midnight found the bridge lights

all out, and was immediately seized. Supposing it an attempt at robbery, he

broke away, and his pursuers stumbling over him, he escaped.

ARREST OF COLONEL WASHINGTON

AND OTHERS.

The next appearance of the

insurrectionists was at the house of Colonel Lewis Washington, a large

farmer and slave-owner, living about four miles from the ferry. A party,

headed by Cook, proceeded there, and rousing Colonel Washington, told him he

was their prisoner. They also seized all the slaves near the house, took a

carriage horse, and a large waggon with two horses. When Colonel Washington

saw Cook, he immediately recognized him as the man who had called upon him

some months previous, to whom he had exhibited some valuable arms in his

possession, including an antique sword presented by Frederick the Great to

George Washington, and a pair of pistols presented by Lafayette to

Washington, both being heir-looms in the family. Before leaving, Cook wanted

Colonel Washington to engage in a trial of skill at shooting, and exhibited

considerable skill as a marksman. When he made the visit on Sunday night he

alluded to his previous visit, and the courtesy with which he had been

treated, and regretted the necessity which made it his duty to arrest

Colonel Washington. He, however, took advantage of the knowledge he had

obtained by his former visit to carry off all the valuable collection of

arms, which the Colonel did not re-obtain till after the final defeat of the

insurrection.

From Colonel Washington's he

proceeded with him as a prisoner in the carriage, and twelve of his negroes

in the waggon, to the house of Mr. Alstadt, another large farmer, on the

same road. Mr. Alstadt and his son, a lad of sixteen, were taken prisoners,

and all their negroes within reach forced to join the movement. He then

returned to the Armory at the Ferry.

THE STOPPAGE OF THE RAILROAD

TRAIN.

At the upper end of the town

the mail train arrived at the usual hour, when a coloured man, who acted as

assistant to the baggage-master, was shot, receiving a mortal wound, and the

conductor, Mr. Phelps, was threatened with violence if he attempted to

proceed with the train. Feeling uncertain as to the condition of affairs,

the conductor waited until after daylight before he ventured to proceed,

having delayed the train six hours.

Luther Simpson,

baggage-master of the mail- train, gives the following particulars: I walked

up the bridge; was stopped, but was afterward permitted to go up and see the

captain of the insurrectionists; I was taken to the Armory, and saw the

captain, whose name is Bill Smith; I was kept prisoner for more than an

hour, and saw from five to six hundred negroes, all having arms; there were

two or three hundred white men with them; all the houses were closed. I went

into a tavern kept by Mr. Chambers; thirty of the inhabitants were collected

there with arms. They said most of the inhabitants had left, but they

declined, preferring to protect themselves; it was reported that five or six

persons had been shot.

Mr. Simpson was escorted back

over the bridge by six negroes.

THE STATE OF AFFAIRS AT

DAYBREAK.

It was not until the town

thoroughly waked up, and found the bridge guarded by armed men, and a guard

stationed at all the avenues, that the people saw that they were prisoners.

A panic appears to have immediately ensued, and the number of

insurrectionists was at once largely increased. In the mean time a number of

workmen, not knowing anything of what had occurred, entered the Armory, and

were successively taken prisoners, until at one time they had not less than

sixty men confined in the Armory. These were imprisoned in the engine-house,

which afterward became the chief fortress of the insurgents, and were not

released until after the final assault. The workmen were imprisoned in a

large building further down the yard.

EARLY CASUALTIES.

A coloured man, named

Hayward, a railroad porter, was shot early in the morning for refusing to

join in the movement.

The next man shot was Joseph

Burley, a citizen of Perry. He was shot standing in his own door. The

insurrectionists by this time, finding a disposition to resist them, had

withdrawn nearly all within the Armory grounds, leaving only a guard on the

bridge.

About this time, also, Samuel

P. Young, Esq., was shot dead. He was coming into town on horseback,

carrying a gun, when he was shot from the Armory, receiving a wound of which

he died during the day. He was a graduate of West Point, and greatly

respected in the neighbourhood for his high character and noble qualities.

The lawn in front of the

engine-house after the assault presented a dreadful sight. Lying on it were

two bodies of men killed on the previous day, and found inside the house;

three wounded men, one of them just at the last gasp of life, and two others

groaning in pain. One of the dead was Brown's son. Oliver, the wounded man,

and his son Watson, were lying on the grass, the father presenting a gory

spectacle. He had a severe bayonet wound in his side, and his face and hair

were clotted with blood.

APPEARANCE OF THE PRISONERS.

When the insurgents were

brought out, some dead, others wounded, they were greeted with execrations,

and only the precautions that had been taken saved them from immediate

execution. The crowd, nearly every man of which carried a gun, swayed with

tumultuous excitement, and cries of "Shoot them! shoot them !" rang from

every side. The appearance of the liberated prisoners, all of whom, through

the steadiness of the marines, escaped injury, changed the current of

feeling, and prolonged cheers took the place of howls and execrations.

BROWN'S EXAMINATION.

A short time after Captain

Brown was brought out, he revived and talked earnestly to those about him,

defending his course, and avowing that he had done only what was right. He

replied to questions substantially as follows : "Are you Captain Brown, of

Kansas?" "I am sometimes called so." "Are you Ossawatamie Brown?" "I tried

to do my duty there." "What was your present object ?" "To free the slaves

from bondage." "Were any other persons but those with you now connected with

the movement?" "No." "Did you expect aid from the North?" "No; there was no

one connected with the movement but those who came with me." "Did you expect

to kill people to carry your point?" "I did not wish to do so, but you force

us to it." Various questions of this kind were put to Captain Brown, which

he answered clearly and freely, with seeming anxiety to vindicate himself.

He urged that he had the town at his mercy that he could have burned it, and

murdered the inhabitants, but did not; he had treated the prisoners with

courtesy, and complained that he was hunted down like a beast. He spoke of

the killing of his son, which he alleged was done while bearing a flag of

truce, and seemed very anxious for the safety of his wounded son. His

conversation bore the impression of the conviction that whatever he had done

to free the slaves was right; and that, in the warfare in which he was

engaged, he was entitled to be treated with all the respect of a prisoner of

war.

CAPTURE OF ARMS.

During Tuesday morning, one

of Washington's negroes came in and reported that Captain Cook was on the

mountain, only three miles off; about the same time some shots were said to

have been fired from the Maryland hills, and a rapid fusilade was returned

from Harper's Ferry. The Independent Grays of Baltimore immediately started

on a scouting expedition, and in two hours returned with two waggons loaded

with arms and ammunition, found at Captain Brown's house.

The arms consisted of boxes

filled with Sharp's rifles, pistols, &c., all bearing the stamp of the

Massachusetts Manufacturing Company, Chicopee, Mass. There were also found a

quantity of United States ammunition, a large number of spears, sharp iron

bowie-knives fixed upon 1)0105, a terrible looking weapon, intended for the

use of the negroes, with spades, pickaxes, shovels, and everything else that

might be needed thus proving that the expedition was well provided for, that

a large party of men were expected to be armed, and that abundant means had

been provided to pay all expenses.

How all these supplies were

got up to this farm without attracting observation, is very strange. They

are supposed to have been brought through Pennsylvania. The Grays pursued

Cook so fast that they secured a part of his arms, but with his more perfect

knowledge of localities, he was enabled to evade them.

TREATMENT OF BROWN'S

PRISONERS.

The citizens imprisoned by

the insurrectionists all testify to their lenient treatment. They were

neither tied nor insulted, and, beyond the outrage of restricting their

liberty, were not ill- used. Capt. Brown was always courteous to them, and

at all times assured them that they would not be injured. He explained his

purposes to them, and while he had them (the workmen) in confinement, made

no abolition speech to them. Colonel Washington speaks of him as a man of

extraordinary nerve. He never blanched during the assault, though he

admitted in the night that escape was impossible, and that he would have to

die. When the door was broken down, one of his men exclaimed, "I surrender."

The Captain immediately cried out, "There's one surrenders; give him

quarter;" and at the same moment fired his own rifle at the door.

During the previous night he

spoke freely with Colonel Washington, and referred to his sons. He said he

had lost one in Kansas and two here. He had not pressed them to join him in

the expedition, but did not regret their loss—they had died in a glorious

cause.

BROWN'S PAPERS AND STORES.

On the i8th a detachment of

marines and some volunteers made a visit to Brown's house. They found a

large quantity of blankets, boots, shoes, clothes, tents, and fifteen

hundred pikes, with large blades affixed. They also discovered a carpet-bag,

containing documents throwing much light on the affair, printed

constitutions and by-laws of an organization, showing or indicating

ramifications in various States of the Union. They also found letters from

various individuals at the North—one from Fred. Douglass, containing ten

dollars from a lady for the cause; also a letter from Gerrit Smith about

money matters, and a check or draft by him for $100, indorsed by the cashier

of a New York bank, name not recollected. All these are in possession of

Governor Wise.

HIS WARNING TO THE SOUTH.

Reporter of the Herald.—I do

not wish to annoy you; but, if you have any thing further you would like to

say, I will report it.

Mr. Brown—I have nothing to

say, only that I claim to be here in carrying out a measure I believe

perfectly justifiable, and not to act the part of an incendiary or ruffian,

but to aid those suffering great wrong. I wish to say, furthermore, that you

had better—all you people at the South—prepare yourselves for a settlement

of that question that must come up for settlement sooner than you are

prepared for it. The sooner you arc prepared the better. You may dispose of

me very easily. I am nearly disposed of now; but this question is still to

be settled— this negro question, I mean; the end of that is not yet. These

wounds were inflicted upon me —both sabre cuts on my head and bayonet stabs

on different parts of my body—some minutes after I had ceased fighting, and

had consented to a surrender, for the benefit of others, not for my own.

(This statement was vehemently denied by all around.) I believe the Major

(meaning Lieutenant J. B. Stuart, of the United States Cavalry) would not

have been alive—I could have killed him just as easy as a mosquito when he

came in, but I supposed he came in only to receive our surrender. There had

been loud and long calls of "surrender" from us—as loud as mcii could

yell—but in the confusion and excitement I suppose we were not heard. I do

not think the Major, or any one, meant to butcher us after we had

surrendered.

BROWN'S VIEWS.

Brown has had a conversation

with Senator Mason, which is reported in the Herald. The following is a

verbatim report of the conversation :-

Mr. Mason.—Can you tell us,

at least, who furnished money for your expedition?

Mr; Brown.—I furnished most

of it myself. I can not implicate others. It is by my own folly that I have

been taken. I could easily have saved myself from it had I exercised my own

better judgment, rather than yielded to my feelings.

Mr. Mason.—You mean if you

had escaped immediately?

Mr. Brown.—No; I had the

means to make myself secure without any escape, but I allowL' myself to be

surrounded by a force by being too tardy.

* * * * * *

Mr. Mason.—But you killed

some people passing along the streets quietly.

Mr. Brown.—Well, sir, if

there was any thing of that kind done it was without my knowledge. Your own

citizens, who were my prisoners, will tell you that every possible means was

taken to prevent it. I did not allow my men to fire, nor even to return a

fire, when there was danger of killing those we regarded as innocent

persons, if I could help it. They will tell you that we allowed ourselves to

be fired at repeatedly, and did not return it.

A By-stander.—That is not so.

You killed an unarmed man at the corner of the house over there (at the

water tank), and another besides.

Mr. Brown.—See here, my

friend, it is useless to dispute or contradict the report of your own

neighbors who were my prisoners.

Mr. Mason.—If you would tell

us who sent you here—who provided the means—that would e information of some

value.

Mr. Brown.—I will answer

freely and faithfully about what concerns myself—I will answer any thing I

can with honor, but not about others.

* * * * *

Mr. Mason.—How many are

engaged with you in this movement? I ask those questions for our own safety.

Mr. Brown.—Any questions that

I can honorably answer I will, not otherwise. So far as I am myself

concerned, I have told every thing truthfully. I value my word, sir.

Mr. Mason.—What was your

object in coming?

Mr. Brown.—We came to free

the slaves, and only that.

A Young Man (in the uniform

of a volunteer company).—How many men in all had you?

Mr. Brown.—I came to Virginia

with eighteen men only, besides myself.

Volunteer,—What in the world

did you suppose you could do here in Virginia with that amount of men?

Mr. Brown.—Young man, I don't

wish to discuss that question here.

Volunteer.—You could not do

any thing.

Mr. Brown.—Well, perhaps your

ideas and mine on military subjects would differ materially.

Mr. Mason.—How do you justify

your acts?

Mr. Brown.—I think, my

friend, you are guilty of a great wrong against God and humanity—I say it

without wishing to be offensive—and it would be perfectly right for any one

to interfere with you so far as to free those you wilfully and wickedly hold

in bondage. I do not say this insultingly.

Mr. Mason.—I understand that.

Mr. Brown.—I think I did

right, and that others will do right who interfere with you at any time and

all times. I hold that the golden rule, "Do unto others as you would that

others should do unto you," applies to all who would help others to gain

their liberty.

HOW HE WAS COMMANDER-IN-CHIEF.

* * * * *

Mr. Mason.—Did you consider

this a military organization, in this paper (the Constitution)? I have not

read it.

Mr. Brown.—I did in some

sense. I wish you would give that paper close attention.

Mr. Mason.—You considered

yourself the Commander-in- Chiefof these "provisional military forces?

Mr. Brown.—I was chosen,

agreeably to the ordinance of a certain document, Commander-in-Chief of that

force.

Mr. Mason.—What wages did you

offer? Mr. Brown.—None.

Lieutenant Stuart.—" The

wages of sin is death."

Mr. Brown' —I would not have

made such a remark to you if you had been a prisoner and wounded in my

hands.

A Bystander.--Did you not

promise a negro in Gettysburg twenty dollars a month?

Mr. Brown.—I did not.

Bystander.—He says you did.

WHAT HE EXPECTED.

* * * * * *

Mr. Vallandigham.—Did you

expect a general rising of the slaves in case of your success?

Mr. Brown.—No, sir; nor did I

wish it. I expected to gather them up from time to time and set them free.

Mr. Vallandigham.—Did you

expect to hold possession here till then?

Mr. Brown.—Well, probably I

had quite a different idea. I do not know that I ought to reveal my plans. I

am here a prisoner and wounded, because I foolishly allowed myself to be so.

You overrate your strength in supposing I could have been taken if I had not

allowed it. I was too tardy after commencing the open attack—in delaying my

movements through Monday night, and up to the time I was attacked by the

Government troops. It was all occasioned by my desire to spare the feelings

of my prisoners and their families and the community at large. I had no

knowledge of the shooting of the negro (Heywood).

Mr. Vallandigham.—What time

did you commence your organization in Canada.

Mr. Brown.-.That occurred

about two years ago, if I remember right. It was, I think, in 1858.

Mr. Vallandigham.—Who was the

secretary?

Mr. Brown.—That I could not

tell if I recollected, but I do not recollect. I think the officers were

elected in May, 1858. I may answer incorrectly, but not intentionally. My

head is a little confused by wounds, and my memory obscure on dates, etc.

PERSONAL APPEARANCE OF THE

INSURGENTS.

A writer in the Baltimore

Exchange, gives the following account of the personal appearance of the

insurgents :-

Old Brown, the leader, is a

small man, with white head, and cold-looking grey eyes. When not speaking

his lips are compressed, and he has the appearance of a most determined man.

His two Sons (one dead) were strikingly alike in their personal appearance.

Each about five feet eleven inches high, with spare visage, sallow

complexion, sunken eyes, and dark hair and beard. The beard was sparse and

long, and their hair long and matted. The wounded man is of undoubted

courage, and from his cold sullen manner, one would suppose did not ask for

or desire sympathy. Anderson, mortally wounded, is tall, black-haired, and

of dark complexion. His appearance is indicative of desperate resolution.

Although suffering the most intense agony from the wound in the abdomen, he

did not complain, or ask for any favour, and the only evidence he gave of

suffering, was occasionally a slight groan. He looks to be thirty years of

age. Stevens, who was wounded on Monday afternoon, and taken prisoner, is

physically a model man. He is five feet eleven inches high, with fine brawny

shoulders and large sinewy limbs, all the muscles finely developed and hard.

He is of dark complexion, and of undoubted resolution. When taken prisoner,

he did not ask or expect quarter, and lay and suffered from his wounds

without complaint other than a groan.

COMMENCEMENT OF THE TRIAL.

A fresh attempt of Brown's to

have the trial postponed in order to obtain counsel from the North having

failed, the case was proceeded with.

The jury having been sworn to

fairly and impartially try the prisoner, the Court directed that the

prisoner might forego the form of standing while arraigned, if he desired

it.

Mr. Botts put the enquiry to

the prisoner, and he continued to lie prostrate on his cot while the long

indictment, filling seven pages, was read:

First—For conspiring with

negroes to produce insurrection,

Second—For treason to the

Commonwealth; and,

Third—For murder.

THE SPEECHES AND THE EVIDENCE.

The case was then opened at

length by Messrs. Harding and Hunter for the Commonwealth, and by Messrs.

Botts and Green for the prisoner.

OLD BROWN ASKS FOR DELAY.

Mr. Brown then arose, and

said : "I do not intend to detain the Court, but barely wish to say, as I

have been promised a fair trial, that I am not now in circumstances that

enable me to attend a trial, owing to the state of my health. I have a

severe wound in the back, or rather in one kidney, which enfeebles me very

much. But I am doing well; and I only ask for a very short delay of my

trial, and I think that I may be able to listen to it; and I merely ask

this, that as the saying is, 'the devil may have his dues'—no more. I wish

to say further, that my hearing is impaired and rendered indistinct in

consequence of wounds I have about my head. I cannot hear distinctly at all

I could not hear what the Court has said this morning. I would be glad to

hear what is said on my trial, and am now doing better than I could expect

to be under the circumstances. A very short delay would be all I would ask.

I do not presume to ask more than a very short delay, so that I may in some

degree recover, and be able at least to listen to my trial, and hear what

questions are asked of the citizens, and what their answers arc. If that

could be allowed me, I should be very much obliged.

At the conclusion of Brown's

remarks, the Court assigned Charles J. Faulkner and Lawson Botts as counsel

for the prisoners.

THE EXAMINATION BEFORE THE

MAGISTRATE.

The examination before the

magistrates then proceeded. The evidence given was much the same as that

which we published last week. It established the main facts charged against

Brown, but showed that he had treated the prisoners humanely. At the close

of the examination, the case was given to the Grand Jury, who found a true

bill next day.

THE ARRAIGNMENT.

At twelve o'clock on the

26th, the Court reassembled. The Grand Jury reported a true bill against the

prisoners, and were discharged.

Charles B. Harding, assisted

by Andrew Hunter, represented the Commonwealth; and Charles J. Faulkner and

Lawson Botts are counsel for the prisoners.

A true bill was read against

each prisoner:

First—For conspiring with

negroes to produce insurrection

Second—For treason to the

Commonwealth; and,

Third—For murder.

The prisoners were brought

into Court accompanied by a body of armed men. They passed through the

streets and entered the Court-house without the slightest demonstration on

the part of the people.

Brown looked somewhat better,

and his eye was not so much swollen. Stevens had to be supported, and

reclined on a mattress on the floor of the Court-room, evidently unable to

sit. He has the appearance of a dying man, breathing with great difficulty.

Before the reading of the

arraignment, Mr. Hunter called the attention of the Court to the necessity

of appointing additional counsel for the prisoners, stating that one of the

counsel (Faulkner) appointed by the County Court, considering his duty in

that capacity as having ended, had left. The prisoners, therefore, had no

other counsel than Mr. Botts. If the Court was about to assign them other

counsel, it might be proper to do so now.

The Court stated that it

would assign them any member of the bar they might select.

After consulting Captain

Brown, Mr. Botts said that the prisoner retained him, and desired to have

Mr. Green, his assistant, to assist him. If the Court would accede to that

arrangement it would be very agreeable to him personally.

The Court requested Mr. Green

to act as counsel for the prisoner, and he consented to do so.

Old Brown addressed the Court

as follows :-

Virginians.—I did not ask for

any quarter at the time I was taken. I did not ask to have my life spared.

The Governor of the State of Virginia tendered me his assurance that I

should have a fair trial; but under no circumstances whatever will I be able

to have a fair trial. If you seek my blood, you can have it at any moment,

without this mockery of a trial. I have had no counsel; I have not been able

to advise with any one. I know nothing about the feelings of my fellow

prisoners, and am utterly unable to attend in any way to my own defence. My

memory don't serve mc; my health is insufficient, although improving. There

are mitigating circumstances that I would urge in our favour if a fair trial

is to be allowed us; but if we are to be farced with a mere forma trial for

execution—you might spare yourselves that trouble. I am ready for my fate. I

do not ask a trial. I beg for no mockery of a trial—no insult—nothing but

that which conscience gives or cowardice would drive you to practise. I ask

again to be excused from the mockery of a trial. I do not even know what the

special design of this examination is. I do not know what is to be the

benefit of it to the Commonwealth. I have now little further to ask, other

than that I may not be foolishly insulted, only as cowardly barbarians

insult those who fall into their power.

THE TRIAL OF JOHN BROWN.

On Monday, 31st ult., Mr.

Griswold summed up for the defence, and Mr. Harding for the Commonwealth of

Virginia.

During most of the arguments

Brown lay on his back, with his eyes closed.

Mr. Chilton asked the Court

to instruct the jury, if they believe the prisoner was not a citizen of

Virginia, but of another State, they cannot convict on a count of treason.

The Court declined, saying

the Constitution did not give rights and immunities alone, but also imposed

responsibilities.

Mr. Chilton asked another

instruction, to the effect that the jury must be satisfied that the place

where the offence was committed was within the boundaries of Jefferson

County, which the Court granted.

A recess was taken up for

half an hour, when the jury came in with a verdict.

There was intense excitement.

Brown sat up in bed while the

verdict was rendered.

The jury found him guilty of

treason, advising and conspiring with slaves and others to rebel, and for

murder in the first degree.

Brown lay down quickly, and

said nothing. There was no demonstration of any kind.

MOTION IN ARREST OF JUDGMENT.

Mr. Chilton moved an arrest

of judgment, both on account of errors in the indictment and errors in the

verdict. The prisoner had been tried for an offence not appearing on the

record of the Grand Jury; the verdict was not on each count separately, but

was a general verdict on the whole indictment.

On the following day Mr.

Griswold stated the point on which an arrest of judgment was asked for in

Brown's case. He said it had not been proved beyond a doubt that he (Brown)

was even a citizen of the United States, and argued that treason could not

be committed against a State, but only against the General Government,

citing the authority of Judge Story; also stating the jury had not found the

prisoner guilty of the crimes as charged in the indictment—they had not

responded to the offences, but found him guilty of offences not charged.

They find him guilty of murder in the first degree, when the indictment

don't charge him with offences constituting that crime.

Mr. Hunter replied, quoting

the Virginia code to the effect that technicalities should not arrest the

administration of justice. As to the jurisdiction over treason, it was

sufficient to say that Virginia had passed a law assuming that jurisdiction,

and defining what constituted that crime.

On the following day the

Court gave its decision as ruling the objections made. In the objection that

treason cannot be committed against a State, he ruled that wherever

allegiance is due, treason may be committed. Most of the States have passed

laws against treason. The objections as to the form of the verdict rendered,

the Court also regarded as insufficient.

The clerk then asked Mr.

Brown whether he had anything to say why sentence should not be passed upon

him.

Mr. Brown immediately rose,

and, in a clear, distinct voice, said: "I have, may it please the Court, a

few words to say. I deny every thing but what I have all along admitted, of

a design on my part to free slaves. I intended, certainly, to have made a

clean thing of that matter, as I did last winter, when I went into Missouri,

and there took slaves without the snapping of a gun on either side, moving

them through the country, and finally leaving them in Canada. I designed to

have done the same thing again on a larger scale. That was all I intended. I

never did intend murder or treason, or the destruction of property, or to

excite or incite slaves to rebellion, or to make insurrection. I have

another objection, and that is, that it is unjust that I should suffer such

a penalty. Had I interfered in the manner in which I admit, and which I

admit had been fairly proved—for I admire the truthfulness and candor of the

greater portion of the witnesses who have testified in this case—had I so

interfered in behalf of the rich, the powerful, the intelligent, the

so-called great, or in behalf of any of their friends, either father,

mother, brother, sister, wife, or children, or any of that class, and

suffered and sacrificed what I have in this interference, it would have been

all right; every man in this Court would have deemcd it an act worthy of

reward rather than punishment.

AN APPEAL TO THE BIBLE.

"This Court acknowledges,

too, as I suppose, the validity of the law of God. I see a book kissed,

which I suppose to be the Bible, or at least the New Testament, which

teaches me that all things whatsoever I would that men should do to me, I

should do even so to them. It teaches me, further, to remember them that are

in bonds as bound with them. I endeavoured to act up to that instruction. I

say I am yet too young to understand that God is any respecter of persons. I

believe that to have interfered as I have done, as I have always freely

admitted I have done, in behalf of His despised poor, is no wrong, but

right. Now, if it is deemed necessary that I should forfeit my life for the

furtherance of the ends of justice, and mingle my blood further with the

blood of my children and with the blood of millions in this slave country,

whose rights are disregarded by wicked, cruel, and unjust enactments, I say

let be done, Let me say one word further. I feel entirely satisfied with the

treatment I have received on my trial. Considering all the circumstances, it

has been more generous than I expected; but I feel no consciousness of

guilt. I have stated from the first what was my intention, and what was not.

I never had any design against the liberty of any person, nor any

disposition to commit treason or incite slaves to rebel or make any general

insurrection. I never encouraged any man to do so, but always discouraged

any idea of that kind. Let me say, also, in regard to the statements made by

some of those who were connected with me. I fear it has been stated by some

of them that I have induced them to join me, but the contrary is true. I do

not say this to injure them, but regretting their weakness. Not one joined

me but of his own accord, and the greater part at their own expense. A

number of them I never saw, and never had a word of conversation with, till

the day they came to me, and that was for the purpose I have stated. Now, I

have done.

HIS TONE AND MANNER.

Brown's speech was delivered

in a calm, slow, unfaltering voice, with no attempt at effect. A

correspondent of the Herald says: -

His composure, and his quiet

and truthful manner while bearing testimony to the great indulgence that had

been extended to him by the Court, throughout the whole of the proceedings,

won the sympathy of every mind present. When he concluded, he quietly sat

down.

In a moment after, he was

escorted back to the prison, for the first time followed by the sympathy of

the people, who gazed upon him with pitying eyes.

His counsel have put in a

bill of exceptions, which will be referred to the Court of Appeals at

Richmond.

HIS SENTENCE.

While Mr. Brown was speaking,

perfect quiet prevailed; and when he had finished the judge proceeded to

pronounce sentence upon him. After a few preliminary remarks, he said that

no reasonable doubt could exist of the guilt of the prisoner; and sentenced

him to be hung in public on Friday, the 2nd of December next.

Mr. Brown received his

sentence with composure.

The only demonstration made

was the clapping of the hands of one man in the crowd,

who is not a resident of

Jefferson County. This was promptly suppressed, and much regret was

expressed by the citizens at its occurrence.

JOHN BROWN IN PRISON

A lady, who visited

Charlestown to assist Mrs. Lydia Maria Child, obtained two interviews with

John Brown, the first of an hour, and the other for a shorter period.

Mrs.—, on entering, found

Captain Brown lying on a cot, and Stephens on a large bed, Captain Brown

arose from his bed to receive his guests, and stood a few moments leaning

against the bedstead, immediately lying down again from weakness. His

visitors were struck with the cheerfulness of his expression, and the

calmness of his manner. He seemed not only passively resigned to his fate,

but cheerful under it, and more than willing to meet it.

She said to him, "I expected

Mrs. Child would be here to introduce me; I am sorry not to find her, for

her presence would make this room brighter for you."

He smiled, and replied, "I

have written to her the reasons why she should not come; but she was very

kind—very kind!"

Some questions were then

asked as to the treatment and care he had received ; to which he said, "I

wish it to be understood by every body that I have been very kindly attended

; for if I had been under the care of father or brother, I could not have

been better treated than by Captain Avis and his family."

HIS STATE OF MIND.

Mrs.- had carried with her

into the jail a large bunch of autumn leaves, gathered in the morning from

the woods. There was no nail on the wall to hang them by, and she arranged

them between the grated bars of the window. She gave to the sufferer a

full-blown rose, which he laid beside his cheek on his pillow. The old man

seemed to be greatly touched with these tokens of thoughtfulness. He is said

to have always been a great lover of nature, particularly of the grandeur of

forest scenes.

Mrs. drew a chair near his

bedside, and taking out her knitting, sat by him for an hour. She has

preserved his complete conversation, of which I can give only a small

portion. She says: "I never saw a person who seemed less troubled or

excited, or whose mind was less disturbed and more clear. His remarks are

pointed, pithy, and sensible. He is not in the least sentimental, and seems

to have singularly excellent common sense about every thing."

HIS PRINCIPLES ON SLAVERY.

She asked him the direct

question,—" Were you actuated, in any degree, in undertaking your late

enterprise, by a feeling of revenge ?" adding that a common impression to

that effect had gone abroad.

He manifested much surprise at this statement, and after pausing a moment,

replied: "I am not conscious of ever having had a feeling of revenge; no,

not in all the wrong done to me and my family in Kansas. But I can see that

a thing is wrong and wicked, and can help to right it, and can even hope

that those who do the wrong may be punished, and still have no feeling of

revenge. No, I have not been actuated by any spirit of revenge."

He talked a good deal about

his family, manifesting solicitude for their comfort after he was gone, but

expressing his great confidence and trust in God's kind providence in their

behalf.

When some allusion was made

to the sentence which he had received, he said, very deliberately and

firmly, and as my friend says, almost sublimely : "I do not think I can

better serve the cause I love so much than to die for it

She says that she can never

forget the impressive manner in which he utterred these solemn words. She

replied It is not the hardest thing than can happen to a brave man to die;

but it must be a great hardship for an active man to lie on his back in

prison, disabled by wounds. Do you not dread your confinement, and are you

not afraid that it may wear you down, or cause you to relax your

convictions, or regret your attempt, or make your courage fail?"

"I can not tell," he replied,

"what weakness may come over me; but I do not think that I shall deny my

Lord and Master Jesus Christ, as I certainly should, if I denied my

principles against slavery."

When the conversation had

proceeded thus far, as it was known outside the jail that a Northern lady

was inside, a crowd began to collect, and although no demonstration of

violence was made, yet there were manifest indications of impatience; so

that the sheriff called to the jailer, and the jailer was obliged to put an

end to the interview.

BROWN'S INTERVIEW WITH HIS

WIFE.

Mrs. Brown arrived at

Charlestown, Dec. i, to see her husband. The interview between them lasted

from four o'clock in the afternoon until near eight o'clock in the evening,

when General Tallaferro informed them that the period allowed had elapsed,

and that she must prepare for departure to the Ferry. Capt. Brown urged that

his wife be allowed to remain with him all night. To this the General

refused to assent, allowing them but four hours.

The interview was not a very

affecting one— rather of a practical character, with regard to the future of

herself and children, and the arrangement and settlement of business

affairs. They seemed considerably affected when they first met, and Mrs.

Brown was for a few moments quite overcome, but Brown was as firm as a rock,

and she soon recovered her composure. There was an impression that the

prisoner might possibly be furnished with a weapon or with strychnine by his

wife, and before the interview her person was searched by the wife of the

jailer, and a strict watch kept over them during the time they were

together.

On first meeting they kissed

and affectionately embraced, and Mrs. Brown shed a few tears, but

immediately checked her feelings. They stood embraced, and she sobbing, for

nearly five minutes, and he was apparently unable to speak. The prisoner

only gave way for a moment, and was soon calm and collected, and remained

firm throughout the interview. At the close they shook hands, but did not

embrace, and as they parted he said, "God bless you and the children!" Mrs.

Brown replied, "God have mercy on you !" and continued calm until she left

the room, when she remained in tears a few moments, and then prepared to

depart. The interview took place in the parlour of Captain Avis, and the

prisoner was free from manacles of any kind. They sat side by side on a

sofa, and after discussing family matters proceeded to business.

THE EXECUTION OF BROWN.

At eleven o'clock on 2nd

December, the prisoner was brought out of the jail, accompanied by Sheriff

Campbell and assistants, and Captain Avis, the jailer. As he came out, the

six companies of infantry and one troop of horse, with General Tallaferro,

and his entire staff, were deploying in front of the jail, while an open

waggon with a pine box, in which was a fine oak coffin, was waiting for him.

Brown looked around, and

spoke to several persons he recognized, and, walking down the steps, took a

seat on the coffin box along with the jailer, Avis. He looked with interest

on the fine military display, but made no remarks. The waggon moved off;

flanked by two files of riflemen in close order. On reaching the field the

military had already full possession. Pickets were established, and the

citizens kept back, at the point of the bayonet, from taking any position

but that assigned them.

Brown was accompanied by no

ministers, he desiring no religious services either in the jail or on the

scaffold.

JOHN BROWN OF OSAWATOMIE.

JOHN BROWN, of Osawatomie,

Spake on his dying day:

"I will not have, to shrive my soul,

A priest in Slavery's pay;

But, let some poor slave-mother,

Whom I have striven to free,

With her children, from the gallows-stair,

Put up a prayer for me.

John Brown, of Osawatomie,

They led him out to die,

When lo, a poor slave-mother,

With her little child, pressed nigh.

Then the bold, blue eye grew tender,

And the old, harsh face grew mild,

As he stooped between the jeering ranks

And kissed the negro's child - Whittier.

On reaching the field where

the gallows was erected, the prisoner said, "Why, are none but military

allowed in the inclosure? I am sorry citizens have been kept out." On

reaching the gallows, he observed Mr. Hunter and Mayor Green standing near,

to whom he said, "Gentlemen, good-by!" his voice not faltering.

ON THE GALLOWS.

The prisoner walked up the

steps firmly, and was the first man on the gallows. Avis and Sheriff

Campbell stood by his side, and after shaking hands and bidding an

affectionate adieu, he thanked them for their kindness, when the cap was put

over his face, and the rope around his neck. Avis asked him to step forward

on the trap. He replied, "You must lead me, I can not see." The rope was

adjusted, and the military order given, "Not ready yet." The soldiers

marched, countermarched, and took position as if any enemy were in sight,

and were thus occupied for nearly ten minutes, the prisoner standing all the

time. Avis inquired if lie was not tired. Brown said, "No, not tired ; but

don't keep me waiting longer than is necessary.

While on the scaffold Sheriff

Campbell asked him if he would take a handkerchief in his hand to drop as a

signal when he was ready. He replied, "No, I do not want it; but do not

detain me any longer than is absolutely necessary."

He was swung off at fifteen

minutes past eleven. A slight grasping of the hands and twitching of the

muscles were seen, and then all was quiet.

The body was several times

examined, and the pulse did not cease until thirty-five minutes had passed.

The body was then cut down, placed in a coffin, and conveyed under military

escort to the depot, where it was put in a car to be carried to the ferry by

a special train at four o'clock.

JOHN BROWN'S AUTOGRAPH.

One of the jail-guard, a

worthy gentleman of this place, asked of Captain Brown his autograph, He

expressed the kindest feeling for him, and said he would give it upon this

consideration— that he should not make a speculation out of it. The

gentleman never alluded to the subject again, but on the morning of

execution Brown sent for him, and handed him the following communication:-

CHARLESTOWN, Va., December,

2nd, 1859.

I, John Brown, am now quite

certain that the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away but

with blood. I had, as I now think, vainly flattered myself that, without

much bloodshed, it might be done.

VICTOR HUGO ON JOHN BROWN.

The following is part of an

address which has been published:-

When we we reflect on what

Brown, the liberator, the champion of Christ, has striven to effect, and

when we remember that he is about to die, slaughtered by the American

Republic, the crime assumes the proportions of the nation which commits it;

and when we say to ourselves that this nation is a glory of the human race;

that—like France, like England, like Germany—she is one of the organs of

civilization; that she sometimes even outmarches Europe by the sublime

audacity of her progress; that she is the queen of an entire world ; and

that she bears on her brow an immense light of freedom, we affirm that John

Brown will not die, for we recoil, horror-struck, from the idea of so great

a crime committed by so great a people.

In a political light, the

murder of Brown would be an irreparable fault. It would penetrate the Union

with a secret fissure, which would in the end tear it asunder. It is

possible that the execution of Brown might consolidate slavery in Virginia,

but it is certain that it would convulse the entire American democracy. You

preserve your shame, but you sacrifice your glory.

In a moral light, it seems to

me that a portion of the light of humanity would be eclipsed—that even the

idea of justice and injustice would be obscured on the day which should

witness the assassination of emancipation by liberty.

As for myself, though I am

but an atom, yet being, as I am, in common with all other men, inspired with

the conscience of humanity, I kneel in tears before the great starry banner

of the New World, and with clasped hands, and with profound and filial

respect, I implore the illustrious American republic, sister of the French

republic, to look to the safety of the universal moral law, to save Brown,

to throw down the threatening scaffold of the 16th of December, and not to

suffer, beneath its eyes, and I add, with a shudder, almost by its fault,

the first fratricide be outdone.

For—yes, let America know it,

and ponder it well—there is something more terrible than Cain slaying

Abel—it is Washington slaying Sparticus.

VICTOR HUGO.

Hauteville House, Dec. 2,

1859.

|