IMMEDIATELY after the rising of

Assembly the Superintendent paid a short visit to his family, but even

these few days were filled up with interviews, correspondence, and

meetings, and in a very few weeks he was once more on the Western trails.

Settlement had been rapidly

extending during the summer in the country lying north and west, towards

Prince Albert and Battleford. And, indeed, far beyond that outpost, on the

way towards Edmonton, settlers had planted their homes upon the wide and

trackless prairie. Hence they must be followed and cared for. From a point

fifteen miles north of Fort Qu’Appelle on his way to Prince Albert, in

company with the Rev. Mr. McWilliams, who is to be installed as minister

of that field, the Superintendent writes to his wife under date, September

25th, 1883, giving the following description of the country through which

he is passing:

"The country south of the Qu’Appelle

Valley, i. e., between Qu’Appelle Station and Fort Qu’Appelle, is

rolling, with a few bushes and pond holes. Owing to the dry weather these

are dry. There were but few settlers’ houses to be seen, and only two or

three patches of grain broke the monotony of the unreclaimed waste. I

understand that a company owns much of the land, and if so, it is evident

that these companies are proving a curse and not a blessing—hindering

rather than helping settlement." He is somewhat before his time. Not yet

have the people of Canada come to the determination that the lands of the

Dominion shall be held or sold for the good of the Dominion and its

people, and not for that of any company or corporation so ever. "Fort Qu’

Appelle is as attractive as ever. It lies in the valley at the east end of

a lake, with the Qu’Appelle River flowing past. To the east, within a

mile, another lake gleams in the sun. To the north the brown hills, deeply

furrowed, look down upon it, with a few whitewashed, thatch-covered

buildings used by the mounted police as barracks nestling at their foot.

On the south rise the banks, as on the north, to a height of about three

hundred feet, but their face is softened with clumps of poplar that now

are yellow and rich. Through the valley, which is about a mile wide, are

scattered houses that were and are used as private residences, stores,

stopping-places, and stables. The Hudson’s Bay Fort is like the majority

of their buildings, and with a stockade which is no longer kept in repair.

The town itself has grown a good deal since I saw it last year. There are

several good buildings, and more are in course of erection. One large

hotel is being built." This was one of the new fields erected the year

before, and the Superintendent is pleased to note the good work done. "Mr.

Brown, our missionary in the district, held services here last summer,

occupying some five other posts besides this. The place of meeting is a

hall built by Mr. Arch. McDonald. This hall is used for public gatherings

of all kinds, whether social, political, or religious. The company owning

it charge $2 per Sabbath for the use of it. No doubt this will give fair

interest on the capital! . . . . . . On inquiring, we found that a good

deal of land is settled upon, and Mr. McDonald of Fort Qu’Appelle informed

us that within twenty miles of the Fort scarcely a good section of

Government land was unallotted. The settlers are principally Canadian,

although there is a sprinkling of French half-breeds, and English and

Scotch. Mr. Brown was the only missionary of any Church that held services

here, and his work was very much appreciated." But there can be no delay.

They must make Prince Albert as soon as possible, for Mr. Sieveright, the

minister in charge, is anxious to leave the field, so on they go.

"To-morrow we drive forty-five miles and stop, they say, at Touchwood

Hills. We have a bed here to-night, and will have a house for shelter

every night but one, when we must be content with a small tent. Provisions

we carry with us, including a boiled ham. Canned meats and biscuit

constitute the staple of our fare. I will try and send you a note

tomorrow. Waggons and carts go down all the time and I may be able to get

a letter sent. Telegraph line goes all the way to Humboldt."

The following day he writes from

Touchwood Hills, giving a vivid picture of his experience on the trails:

"Another day’s journey is over, and

we have just disposed of our supper and are at leisure for a short time.

The Hudson’s Bay post is within half a mile of us, and I propose to go

down and hold a service there this evening." Let the others stretch their

weary limbs in rest. This man has a message in his heart for these men of

the far-away plains of Canada, and he is, indeed, straitened till it be

delivered. "The day was dry, but somewhat cold. In the morning there was a

frost that would indicate that the thermometer had fallen as low as

twenty-five or twenty-six degrees. It was quite misty at the start, but a

breeze began to blow about eight o’clock and the mist cleared away. We

drove twenty-two or twenty-three miles and had dinner. This distance we

travelled in about four hours, leaving O’Brien’s at six and making our

stopping-place at ten. There was a house, but McLean forgot the key and we

could not get in. We kindled a fire outside and boiled the kettle and had

dinner—bread, canned tongue, butter, and tea. We all relished our meal

after our morning drive. The fire we had to watch carefully to prevent

spreading, and as soon as the kettle was boiled we drowned out the fire.

Tea was black and strong, and our tin, being without a lid, we got a good

infusion of ashes and smoke. . . . . . . Late in the afternoon we passed

at the Touchwood Hills quite a number of teepees and several half-breed

houses. The latter had patches of grain, and much of it was still in the

field. The weather is dry, however, and no doubt all will be safely

stacked. The land at Touchwood is hilly, but the soil is good, and no

doubt in a short time will be settled. We arrived here at five o’clock,

making the twenty-two or twenty-three miles this afternoon in five hours.

To-morrow we are at Salt Plains."

The next day he makes some

twenty-five miles, and camps at night in an old shack, none too

comfortable.

"To-night we are to lodge in a place

7x12, partitioned off from the stable. A lot of hay covers the floor, a

rusty stove is standing in the corner, which, with a rickety table,

constitute the furniture. We found a lantern which will answer for a

light. The side is quite airy, the boards having shrunk a good deal. But I

have a good tuque, or nightcap, and I hope to keep warm enough. I have two

buffalo robes, two pairs of blankets, and other appliances that will

likely keep me comfortable. Three teams besides our own drove in here just

now and are going to remain all night. I think the room will afford

sufficient accommodation to enable us to lie down. To-morrow we expect to

make Humbolt at six."

A letter written the following day

gives an account of his night's experience:

"Last night our quarters were humble

enough. Seven of us lay side by side in the shanty, and the open spaces

let in a good deal of cold. Some of our company were great snorers, the

horses were pawing and coughing, and Mr. McWilliams, I fear, slept but

little. The frost was decidedly sharp when we got up. Breakfasted before

daylight and got a good start before sunrise. The road this morning for

nearly twenty miles lay along the Salt Plain, when we struck higher land

and timber. The day is clear and bright, and travelling comfortable. But

dinner is ready—things are primitive and plain—and I must go to work and

do justice to my share. The plates of the rest of our company, and cups,

were left behind, and Mr. McWilliams and myself eat off the same plate and

drink out of the same cup !"

At this point he meets Sieveright

and pumps him dry in regard to his mission field. In due time, the

Superintendent reaches Prince Albert, spends a couple of days there

getting Mr. McWilliams settled in his charge, perfecting the organization

of the congregation, and making acquaintance with the Presbyterians in the

village and the surrounding country; then once more he takes the trail to

Battleford. The genial days of September are gone, the nights are sharp

with frost, and occasionally the ground is covered with snow, but he makes

light of all discomfort and writes from Battle. ford, under date Oct. 12,

1883, in the following buoyant strain:

"My DEAR WIFE :— "I have just called

at the post-office and find that a mail goes out in a few minutes, and

hence write you a note. We left Prince Albert on Tuesday and got to

Carlton that night. Next morning the ground was covered with snow, but we

got off betimes and reached the Elbow (forty miles) after dark. Camped

beside a willow bush—no trees. Cleared the snow off and spread my oilcloth

and made a bed in the corner of our tent. We got some dry willow and got a

fire made and had a good warm supper. Went to bed and slept soundly. Got

off the next morning in good time, and were going through country overrun

with fire. Found it hard to get wood and water. Camped beside a low swail.

It was empty of water, but we got grass for the horses. I gathered some

snow to make tea (snow nearly all gone), and got a few willow bushes to

make fire. Had a good dinner and started off again, to pass over a rough

hilly country with a few creeks running into the Saskatchewan. (You can

follow our course by the line of railway adopted in McKenzie’s time along

the North Saskatchewan.) Camped at night after going about thirty-five

miles, and got two old telegraph poles to make fire of. Yesterday, we

passed over a rough country, but it was well watered and had plenty of

timber. We got here last night, and I paid the man off ($45 he charged)

and got lodgings with Mr. McKay, of the Hudson’s Bay Company. I have been

trying to hunt up the Presbyterians here and have been partially

successful. I think we must send a man in here to look after them."

He has been only a few hours in the

place after two months’ journey, but he takes no time for rest and

recuperation, but at once sets out to "hunt up Presbyterians," for

Presbyterians he must have at all costs, and that is why he gets them. He

plans to extend his trip to Edmonton, nearly 300 miles away. Ever since

his appointment he has had it in mind to visit that far outpost, but for

two years, to his great regret and to the great disappointment of the

missionary in charge, he has been forced to defer his trip. Now that

Edmonton is only 300 miles away, the weather fine, the roads

excellent, and he himself in fine fettle, he resolves to essay the

journey, and to the great joy of the missionary at that point, after a

week’s hard drive he safely arrives, completing a trip of some 1,200

miles.

His visit to Edmonton proved a great

stimulus to the missionary and the little congregation. Two days he spent

organizing the finances of the congregation, visiting the different

stations in connection with the field, and then bidding farewell to this

brave missionary, A. B. Baird, and his gallant little company, he takes

his homeward journey, leaving both missionary and people greatly

encouraged and much fitter for their winter’s work.

The experiences of the

Superintendent on this north trip give tone and colour to his report to

the Assembly of 1884. Remarkable as was the growth of the previous year,

the expansion of this year was even more extraordinary. The report for

1882 showed forty new fields, that for 1883 showed fifty-one new fields,

but this year the Superintendent is able to report the opening up of

seventy new fields. Between Winnipeg and Edmonton these fields lie

scattered, with great empty spaces between, but organization has been

effected, often the merest skeletons of congregations, it is true, at

these seventy points. And with the growth of settlement the intervening

spaces will be filled up and the skeletons he rounded out into full-grown,

vigorous congregations.

Through the eyes of the

Superintendent, the Assembly begins to get visions of these vast prairie

reaches, and of their possibilities for good to Canada and to the Kingdom

of God therein, and is, therefore, the more easily persuaded to plan

largely for Western work. It is no wonder that the Assembly, reversing the

report of its Home Mission Committee and in response to the prayer of the

Presbytery of Manitoba, agrees that that Presbytery should be divided into

three, to be called Winnipeg, Rock Lake and Brandon, and that these

Presbyteries should be erected into the first Western Synod under the name

of the Synod of Manitoba and the Northwest Territories. It is interesting

to read in the minutes of that Assembly the terms in which are described

the boundaries of the Presbytery at Brandon, that lying farthest to the

West "Presbytery of Brandon. —The Presbytery of Brandon shall embrace the

portions of the Province of Manitoba not included in the preceding

Presbyteries, and the Northwest Territories, and shall include the

following congregations and mission statioiis, and such others as may

hereafter be erected within its bounds."

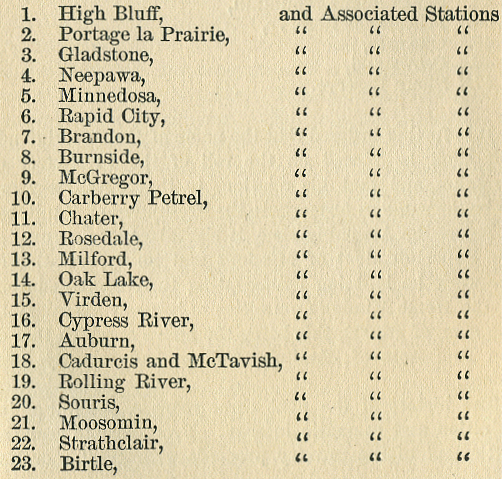

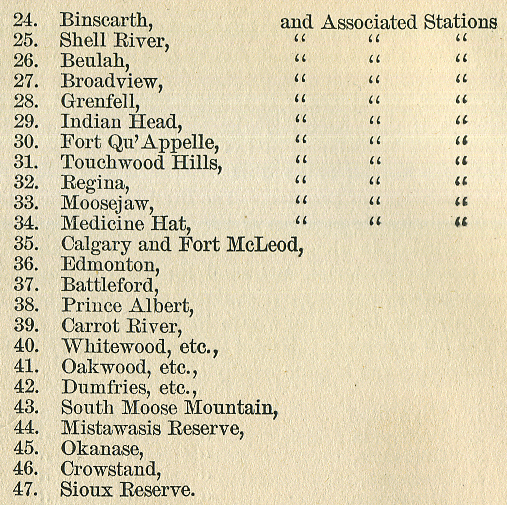

The list of fields in this most

Western Presbytery is also illuminating and is quite worthy of record:

It is further ordered that the name

of the Superintendent shall be placed on the roll of the Presbytery of

Brandon, and that his relations to that Presbytery are to be the same as

formerly to the Presbytery of Manitoba.

Before the Assembly rises, it

signalizes its approval of the Superintendent of Missions and its

appreciation of the work he is doing by accepting the recommendation of

the Home Mission Committee to increase his salary to the sum of $2,000,

this being the figure to which that of the Professors of Manitoba College

had recently been raised.

The history of the next three years

is one full of inspiration and romantic interest. From year to year the

settlement of the country proceeds with greater or less rapidity, and with

the growth of settlement there marches the expansion of mission work.

Farther and ever farther the Superintendent pushes back the limits of his

great mission field. Week after week, month after mouth, both

summer and winter, when he is not engaged in the arduous and difficult

task of extracting revenue from willing and unwilling members of the

Church in the East, he presses his tireless journeys over the prairies by

railroad which now traverses the field from east to west, but mostly by

trail, returning from each journey with some names to add to the rapidly

growing roster of his mission fields, and with his black note-book as well

as his heart and head crammed with additional facts wherewith to quicken

the enthusiasm of his Church and to deepen her sense of responsibility for

the new Empire so rapidly building in the western half of the Dominion.

In the General Assembly of 1885, on

overture from six Ontario Presbyteries and from the Preshytery of Brandon

in the West, the first suggestion of a Summer Session in one of the

colleges is made. This overture the Superintendent strongly supports. The

proposal is remitted to the favourable consideration of the Presbyterian

College of Halifax, which college, however, in the following year declines

to consider the proposal to change the time of its theological session

from the winter to the summer months. And so the Superintendent must

struggle on, doing what he can to man his fields, gathering such recruits

as offer from the Old Land and from the United States.

An overture from the Presbytery of

Brandon transmitted with the approval of the Synod, results in the

erection of the new Presbytery of Regina. The decision of Assembly is

given in the following terms:

"That the prayer of the petition of

Brandon Presbytery, as transmitted through the Synod of Manitoba and the

Northwest Territories, be granted, and a new Presbytery erected; that its

extreme eastern boundary be the western provincial boundary line of the

Province of Manitoba, and that it consist of the following congregations

and Mission stations: Alameda, Battleford, Broad-view, Calgary, Carlisle,

Carrot River, Cathcart, Cut Arm Creek, Dumfries, Edmonton, Fort McLeod,

Fort Qu’ Appelle, Fort Saskatchewan, Green Valley, Grenfell, Indian Head,

Jumping Creek, Long Lake, Medicine Hat, Moosomin, Moosejaw, Pine Creek,

Prince Albert, Qu’Appelle Station, Regina, Southworth, Moose Mountain,

Touch-wood Hills, Whitewood, Wolseley, Yorkton, Broadview Reserve,

Crowstand, Mistawasis Reserve; that the name of the Presbytery be

Regina, that

the Rev. P. S. Living-stone be the first Moderator, and that it hold its

first meeting at Regina, in the church there, on the 15th day of July,

1885, at eleven o’clock."

The newly erected Synod of Manitoba

and the Northwest Territories in 1885, at its second meeting, honours the

Superintendent and itself by choosing him to be its first elected

Moderator. It is the year of the second rebellion. The following letter to

his wife is interesting as furnishing contemporary opinion upon that

unhappy affair:

"Mr. Pitblado, I think I told you in

my last, I went with the Halifax Battalion. Mr. Gordon went off to the

front with the Ninetieth. I presume he is with the troops before now on

the South Saskatchewan. There has been no further conflict there since the

affair of Fish Creek. Middleton has been inactive, why, I do not know.

Some say that he had neither the men nor the ammunition he required. If

not, he was much to blame. He had plenty of time, and why he does not push

on I do not know. Every day he delays is giving the Indians time to

organize and rise, because they think Middleton has been checked if not

defeated. To us the whole affair seems a puzzle. There has been

mismanagement from the outset. I wonder when it will end. To-day tidings

came from Battleford that Colonel Otter had an engagement with the Indians

on Poundinaker’s Reserve. Eight of our troops were reported killed and

double that number wounded. Had there been any despatch in sending troops

up there first, an outbreak at Battleford might have been averted. It is

becoming clear that the men who are managing this whole affair are not

equal to the task. Herchmer and Otter will put Poundmaker and his band

down, but I fear more blood will be spilt yet, and blood spilt now may

mean more hereafter. The quelling of the rebellion will not restore the

confidence nor secure the feeling of safety that existed before. You speak

of this growing to larger proportions than I thought. Consul Taylor told

me last week that his opinions were exactly mine—and he should be a good

judge—and that if the Government had taken hold of the matter promptly,

the end would have been reached long ago. Mr. Gordon and a host of the

best men here are holding the same views. A fire may be a small affair and

easily put out, but let it alone with a lot of inflammable matter around,

and it may take a good deal to cope with it. So it was here. The

dilatoriness of the Government encouraged Indian and halfbreed to rebel or

continue in his rebellion."

By this rebellion the attention of

the whole country is centred upon the Indian and half-breed population of

the West; there is a quickened sense of responsibility to these people,

and, in consequence, the Synod is aggressively Foreign Mission in its

spirit and legislation. But in spite of this, and perhaps, indeed, because

of this, the Superintendent on leaving the Moderator’s chair to present

his report, rouses the Synod to a point of enthusiasm rarely surpassed in

all its subsequent history.

Right there on the Western field and

speaking to Western men from whose eyes experience had torn the glamour

which distance and unfamiliarity often lend to stern realism, he told them

of their own work, showed it to them in its true perspective, related each

little patch of the field to the great whole, threw upon it the golden

colours of the glowing future till as they looked and listened, they were

ready to toil and suffer without murmur or hope of reprieve for the sheer

glory of the work itself, and for His glory whom they had pledged

themselves to serve. It was a triumph, indeed. No man present at that

Synod meeting of 1885 will ever forget that speech and its effect upon the

toil-worn, sun-baked group of missionaries who had travelled from ten to

well-nigh ten hundred miles to be present.

In the autumn of that year the

Superintendent prosecutes two extended tours, one through Southwestern

Manitoba and far south and west beyond the boundaries of the Province, the

other through the ranching country of Southern Alberta. During the first

tour he writes to his wife the following characteristic letter, under

date, Virden, August 13, 1885:

"MY DEAR WIFE : —"Yesterday I

returned from the Moose Mountain country where I had gone to open two

churches. One of them was not finished and was not opened, the other was

finished and opened. I drove on Saturday sixty-five miles, and on Sabbath

morning to the finished church, twenty miles. I rarely saw a finer stretch

of country than lies south of the Moose Miountain. We have a healthy cause

there, although it is not strong. Coming back, I stopped at Green Valley

and attended to work there. Found that some of the people had suffered

much through hail. Some sixteen families of crofters lost a good deal.

I did what I could to encourage and

cheer them. We are thinking of building two churches among these people.

The missionary in Green Valley is a green Glasgow man. I wish Jamesy was

out here to teach him how to harness and drive a horse, and how to ride

one. He got an Indian pony and he (the pony) completely mastered him (the

missionary) so that he (the missionary) had to sell him (the pony). I am

almost afraid the second one will do the same. He has rather contracted

ideas, too, about work, and so I have had to give him a few hints. He

thought a minister’s duty was to preach the Gospel and not to be bothered

with horses. I had to tell him that if he could not reach the people to

whom he preached without a horse, then he must learn to drive and ride—in

fact, that if these were his ideas he had no business in the

Northwest—that I would far rather have a man know less Latin and more

Horse, and that without some knowledge of horses a man was useless. The

man looked amazed, but took all well and is going to work.

"Had the misfortune to break my

buggy spring and mended it on Sunday morning on the road with a

halter strap.

"Moosomin was reached yesterday and

I found a sale of cavalry horses going on. It was interesting to see a

large number of scouts in the late campaign buying their old horses and

taking them home. But I am going away across the river to a meeting. I got

here this morning and have a meeting to-night. Elders are to be ordained

and inducted."

From Fort McLeod he writes on his

second tour a letter, the facts contained in which he afterwards made

public. The publication of these facts awakened a feeling of horror and

shame throughout the whole country and determined the Church to establish

at McLeod at all costs a permanent mission. For this mission an elder in

the city of Ottawa, burning with indignant grief and shame over the

horrible revelations, offered $600 for two years.

The following year the Assembly adds

a further name to the list of its Presbyteries, in the erection of the

Presbytery of Columbia, which is made to include all congregations and

mission stations in British Columbia, and which is connected with the

Synod of Manitoba and the Northwest Territories, though it does not as yet

come under the Superintendent’s jurisdiction.

The report presented by the

Superintendent in 1886 showed that in spite of the rebellion of the year

before and of the continued financial depression, there had been steady

progress made during the year. The number of stations had gone up from 318

to 351, a gain of thirty-three; the number of communicants from 4,457 to

4,769, a gain of 312. In regard to this matter of communicants, the

Superintendent sounds this warning note:

"It will be noticed that there are

not as many communicants as families. Of the young men coming to us, not

fifteen per cent. ever made a profession of faith. There is a source of

danger here should there be neglect."

There is, however, a very cheering

fact to record in regard to the supply of fields. The Church is evidently

beginning to take heed, for the report says:

"During the past summer not a

settlement of any size in the country was left unprovided with ordinances.

Efforts were also put forth to furnish supply during the winter, and with

a good deal of success. There was not a point along the lines of railway

which was left unsupplied, and districts removed from the railway had at

least partial supply. When no other missionaries were available,

catechists were secured for six months, and students of Manitoba College

were employed during the Christmas holidays."

The Superintendent seizes the

opportunity furnished by the taking of the Dominion Census to indulge his

penchant for statistics, and presents to the Assembly certain

valuable and inspiring information, with his reflections thereupon. Among

other facts he notices that out of a total population for the Territories

of 48,362, there are 23,344 whites, and of this number 7,712 are

Presbyterians. He thus estimates that the Presbyterians form over thirty

per cent, of the population of these Territories, as they form over forty

per cent. of the population in Manitoba. This fact he uses to lay heavier

the weight of responsibility for the people of the West, upon the

conscience of the Presbyterian Church.

Towards the end of that year, the

Superintendent makes a swift dash into British Columbia, stirring up the

people wherever he can pause, to organization and self-support. From

Donald, the most ambitious and most ungodly town in British Columbia at

that time, he writes:

"I spent the day at Donald trying to

do two things— to get a church building under way, and to get support for

a minister. I got $600 promised for the minister and got arrangements made

to have the church built, $700 being subscribed in cash and 14,000 feet of

lumber."

The General Assembly for 1887 met in

the city of Winnipeg, a significant testimony to the importance which the

Western metropolis had assumed in the opinion of the Church. It is a Home

Mission Assembly, and the minds of the fathers and brethren are largely

occupied with the expansion of their Western heritage. In the minutes of

that Assembly is found the following very significant paragraph

"On motion of Mr. James Robertson,

seconded by Mr. James Herdman, the following resolution was adopted,— That

the prayer of the Presbytery of Regina be granted, that the General

Assembly hereby erects a new Presbytery to be bounded as follows:" And

then the resolution proceeds to describe the boundaries of the new

Presbytery by lines truly majestic in their sweep: "The eastern limit of

said Presbytery shall be the one hundred and ninth degree of longitude;

the southern limit the forty-ninth parallel of latitude; the western

limit, a line passing north and south through the western crossing of the

Columbia River by the Canadian Pacific Railway ; the northern limit, the

Arctic Sea."

In what magnificent terms these men

conceived their work! Here are the names of the fields constituting this,

the greatest Presbytery the world has ever seen: Indian Head, Lethbridge,

Fort McLeod, High River, Calgary, Edmonton, Fort Saskatchewan, Red Deer,

Cochrane, Banff, Anthracite, Donald, and Revelstoke. And here are the

names of the men to whose care this stupendous Presbytery is entrusted:

Messrs. James Herald, Charles McKiIlop, Richard Campbell Tibb, Angus

Robertson, James C. Herdman, Andrew Browning Baird, Alexander H. Cameron.

By the appointment of Assembly the first meeting of this great Presbytery

is to be held on the third Tuesday of July, 1887, and of this Presbytery

the first Moderator is to be Angus Robertson, well known and greatly loved

by all who toiled with him as a Western missionary during his all too

brief life.

By this Assembly, also, the eastern

boundaries of the Presbytery of Winnipeg are extended to White River, a

point 248 miles east of Port Arthur, the former boundary.

To this Assembly the Superintendent

presents a brief report of the work accomplished during the five years

that have just passed. It is characteristic of the report that there is

absolutely no hint or suggestion of the toils and tribulations, of the

perils and privations, that he has endured, to whom, under God, the great

results achieved have been largely due. It is a record of truly

magnificent progress, and of startling achievement. When he came to his

work as Superintendent, he found 116 Mission stations scattered throughout

Manitoba and the neighbouring parts of the Territories. His first report

gave the names of 129 fields lying, for the most part, within a radius of

about 200 miles of Winnipeg, isolated from each other, unknown to the

Church, uncared for in any adequate manner, financially hopeless, and

provided only with supply of the most spasmodic kind. Beyond these 129

fields lay new settlements without missionary or Church services, and over

the whole West were hundreds and thousands of undiscovered Presbyterians.

In five years what a change! Instead

of 129 stations there are reported 389, a growth of 260, fifty-two for

every year, one for every week of that period, and almost every station

the result of a personal visit of the Superintendent, and in almost every

case of his personal organization. His first report showed a commuicant

roll of 1,355 for all the West; the report for 1887 showed 5,623.

When he came to his field the Presbytery of Manitoba had knowledge of only

971 families. In a single year he discovered 1,000 more and placed these

formerly unknown and isolated families into Church homes, and during the

five years he discovered and set in Church relation over 3,000

Presbyterian families. When he took into his hands the reins of

superintendency, he found in all the West some fifteen churches. Before

five years were over there were nearly 100, and these the result largely

of the help given by the Church and Manse Building Fund, whose creator he

practically was.

In Eastern Canada the results

achieved were no less extraordinary. In 1882, the Western Missions were

practically unknown to the Church in the East. The Home Mission cause held

an insignificant place in the mind of the Church, the appeal for funds

brought very inadequate response. But before five years had passed, by his

reports, his speeches, his sermons and addresses, the Superintendent had

made the West visible, and brought it near. More than that, becoming

visible and real to the Church in Eastern Canada, the West and its

marvelous mission work acted as a magnet for the unifying of the different

parts and varied elements of the Church in the East. Home Missions began

to bulk large and the Church awakened to a new self-consciousness by

reason of this great mission enterprise she was carrying on in Western

Canada. In short, by the work of these five years the straggling,

scattered missions in Western Canada, the disintegrated and isolated

fragments of a Church, unknown to each other and to the Church as a whole,

were organized into one body whose members fitly framed and compactly

joined together by that which every joint sup plied, began to grow with a

common life into a Church pulsing with vigour, conscious of power, and

alert for the mighty enterprise laid to her hand by her Lord.

The Assembly of 1887, meeting for

the first time in the capital of Western Canada, received many courtesies

from various public and civic bodies, but none was more appreciated than

the invitation of the Canadian Pacific Railway to visit the Pacific Coast;

and few greater pleasures ever came to the Superintendent during his life

than that he experienced in conducting the Commissioners across the

reaches of his mission field. It was from first to last an experience of

wonder and delight to the whole party, and of pride and joy to the

Superintendent who organized and conducted it. One incident in the journey

across the plains is worth recording. It is given in the words of an

eye-witness:

"I shall never forget one scene.

While on the way westward, we arrived at some point where the train was to

stop for some minutes, for water, I think. There was nothing but a station

in sight. Being towards dusk, he proposed that the whole party should

gather on the prairie during the stop, for worship. It was heartily

responded to, and the words of a familiar Psalm floated on the breeze from

a hundred voices, followed by. a brief prayer. It was like a consecration

of the boundless open space to the service of Christ, and of ourselves, as

representing the Church, to its evangelization, when it should be

occupied, as he believed it soon would."

His faith in the West never

faltered, and every succeeding year only served to justify it. His work

through the years that followed was in detail largely a repetition of that

of the five years just passed. Failure never checked him, success never

sated him, but day by day and week by week until the very last, he

followed the gleaming steel or the black line of the trail across the

prairies and through the mountains, eager, insatiable, undaunted.