|

In January 1919 I addressed

a meeting of the merchants and manufacturers in Los Angeles at their

urgent request at which there were four hundred present. The Foreign

Trade Committee of the Chamber of Commerce was also present.

ADDRESS BEFORE MERCHANTS

AND MANUFACTURERS

The question that is

troubling all thinking men today is: How are we going to operate our

ships after the war? Seeing that in normal times our present laws and

regulations make it a financial impracticability, we must not be carried

away with the present abnormal condition and rates of freight, which

make it quite possible for anyone to make a profit, no matter how

inexperienced. So all the figures and considerations in this article are

based on normal conditions which are sure to come after the war.

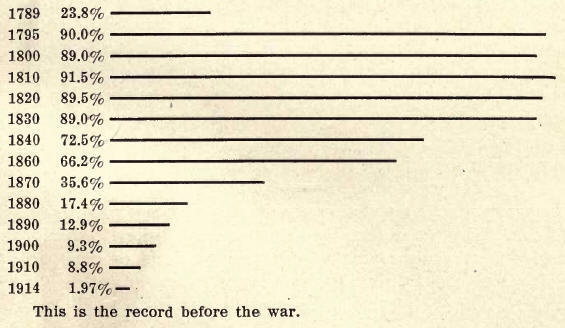

So that you may fully

understand the folly of our past legislation, I herewith give you a copy

of a diagram prepared by Mr. P. W. II. Ross, showing the percentage of

American goods carried in American ships in years gone by.

This was during the

period of preferential duties.

Another illustration that

would not be out of place here is one showing the conditions on the

Pacific Ocean up to May, 1917. In 1913, before the war and before the

Seamen's Bill had gotten in its deadly work, Japanese vessels in

American trade on the Pacific were, 26.05%; American vessels, 26.10%.

After May 1, 1917,

Japanese vessels increased their trade to 50.90%, while the trade of

American vessels (as a result of the Seamen's Bill) fell off to 1.97%.

The following records,

taken from our books, is the cost, per month of the crew's wages on

three steamers which we were operating in 1914. The indicated horsepower

of the vessels was exactly the same and the tonnage nearly the same. The

difference in man power is due to governmental regulation: American

steamer, 47 men, $3270; British steamer, 36 men. $1308; Japanese

steamer, 36 men, $777.

On the Pacific the keen

competition Americans have to meet is from the Japanese, and after the

war this competition wiill also be felt oil the Atlantic. The foregoing

figures give a good idea of what our handicaps are. Japanese shipowners

made enormous profits during the war; therefore, competition with the

Japanese will be backed by plenty of money on their side, in addition to

their having subsidies for shipbuilding and for carrying the mails, and

other advantages that American shipowners must combat. There is some

talk of our government chartering its ships to individuals after the war

and not selling them. This will be a fatal mistake. The men, who in the

past developed American and British foreign trade, were shipowners. Ship

charterers having no money invested, will operate the ships only as long

as they can make a profit. Responsible shipowners will keep up the

business even at a loss, and stay with the business until times get

better, thereby keeping up the foreign trade of our country.

At a banquet in

Philadelphia the Secretary of the Navy announced the contemplated

extension of government ownership, to own and operate American ships and

to engage in foreign trade; thereby destroying the private ownership of

ships and going into competition against our merchants in the foreign

trade. (Our Government has already started to trade commercially, I

understand, in Siberia.) The result of this policy would be to destroy

the initiative,' "pep" and "getup" of our merchants in that trade and

the few shipowners we have left; and this while we are on the even of

the keenest competition the world has ever seen. Then, in addition to

all this, we were told that the rates of freight would be lower than

those of our foreign competitors. (The foreigners will have something to

say about the rates.) In as much as we are in direct competition m our

foreign trade, and as our country is going to require this trade as

never before, it is the opinion of our bankers, merchants and the people

generally that the administration has another guess coming before it

will be permitted to carry out such a destructive and disastrous policy.

I suggest that, instead

of government ownership, the ships should be sold at prices to meet

competition and on reasonable terms of payment, so as to encourage the

ownership of ships by men of moderate means.

Example: Government ships

should be sold at the current price of similar ships and on the same

terms prevailing in London; one quarter cash, one-quarter in one, two

and three years, with interest at 4% per annum, and when the various

payments fall due the amount to be paid shall be the price prevailing

then in London, thereby putting our shipowner on an exact equality with

our foreign competitors as to the first cost of the ship. In other

words, keeping the cost of the ships so bought equal to the cost of

foreign ships while the owner is paying for them. 'The difference in

cost to the Government and the amount sold for, to be charged to the

cost of the war, the same as ammunition, etc.

Wages: As explained, the

wages of the crew is a very important matter; and, as the American

cannot be brought down to the level of his foreign competitior, any more

than the foreigner can be raised to the level of the American, the

American will, as a consequence, leave the sea unless he can get about

the same wages as he would receive on shore. I offer as a solution of

this condition, that shipowners hire their crews at full American wages,

but that the difference between this wage and what is paid by Japanese

competitors be paid by the Government to shipowners on proper

certification by the shipping commissioner of the amounts so paid.

As for example, if the

wages of the American seaman is $60 per month, that of the Japanese

seaman $15 per month, then have the United States Government pay the $45

per month difference. This will enable American labor to receive its

full wage and permit the American ship to compete with its foreign

rivals in trade with their lower paid crews. This is no subsidy to

shipowners, but only an equalization of American vs. foreign labor.

To those who are not

familiar with the custom I would explain that when a man hires to work

on a ship he must go before a United States commissioner and sign the

articles of contract, which is explained to the man by the commissioner.

Then, when the voyage is ended, the shipowner does not pay off the crew,

but takes the money to the commissioner, who pays the men. By this

arrangement the men would receive the full American wages, and such fine

young Americans as are now being trained in great numbers would be sure

to continue to follow the sea, if the entire crew of a ship were

composed of Americans. And especially if that vicious clause in the

Seamen's Act is abrogated, which provides that 65% of the crew must be

certificated able seamen; no other nation calls for such regulations,

and, if it were enforced, would tie up half of our ships, as there are

not nearly enough of so-called able seamen to man half our vessels.

The manner of licensing

our officers must also be modified so as to be the same as our

competitors.

In ships running to the

tropics, Americans will not stand the work in the hot fireroom. and in

that trade it is also a question if Americans would work in the

steward's department. All American owners have had this experience.

American sailors on deck, however, get along all right. Outside of the

equalization of wages of the men, and the proper payment for service

rendered in carrying the mails, I claim that to maintain American ships

on the ocean no other financial assistance by the Government is required.

But our laws and

regulations must be radically changed, not in such a way as to give

shipowners any advantage over their competitors, but to put our ships on

an exact footing with those of all other nations. To do this it will not

cost our country a cent, except in equalizing wages.

Following are some of the

changes in our laws that are necessary. For example, the standard

steamer of 8800 tons deadweight, of which scores are being built for the

Shipping Board.

The steamer Robert

Dollar, of which all these are duplicates, according to British

measurement, has a net tonnage of 3420 tons; under American measurement

she will average net 4283 tons, a difference of 863 tons. Since all port

charges, pilotage, drydocking, etc., are based on the net tonnage of a

vessel, the American ship in foreign trade pays 25% more than the ships

of any other nation; and, since this is paid in foreign ports and to

foreign nations, is it not up to Congress to tell us why our ships are

thus penalized?

(Note—The laws of Great

Britian and ours, as to measurement, are about the same, but in the

application of the law there is a difference. The fact remains, however,

that the actual difference is as stated.)

(Note—In November, 1921,

it is reported that the American Government has at last capitulated and

changed its form of measurement to correspond with the British method.

It has taken twenty-five years to accomplish this reform.)

In an address delivered

by Colonel Goethals in San Francisco we were told of two sister ships,

one under the British flag and the other under the American flag. The

latter paid $500 more tolls than the Britisher. I would again ask

Congress, why? In this connection it might be pertinent to ask why an

American ship carrying a cargo of lumber pays more tolls than a ship

carrying merchandise, coal or iron.

Under American

regulations, the ship must be free of cargo, and the boilers filled with

cold water; therefore, handling of cargo must be suspended, and the

inspection must be completed before work is again resumed. On British

ships no work stops. One part of the inspection is finished; then, when

another part of the hull, boilers or engines is ready, that is

inspected, and if the inspection cannot be completed the vessel is

allowed to proceed to the next port, where it can be finished. The

instructions to the inspector are, not to stop the ordinary work of

handling cargo. In the successful operation of ships, one of the most

important factors is then quick dispatch in port.

The American regulations

require a cold water hydrostatic pressure, once and a half the working

pressure, to be applied to the boilers once a year; this racks the

boilers and piping, causes much expense and shortens the life of the

boilers. This method is not required annually by any other nation, and

they have no more explosions of boilers than those inspected under the

American plan. American rules require a fusible plug in each boiler.

This is not required by any other government. The loss of time and

expense to American ships is considerable. Again I ask, why? Especially,

when no benefit is derived by this loss of time or money. In my opinion,

more inspectors should be employed and the regulations entirely changed,

thus enabling our ships to gain much valuable time.

Secretary Redfield, under

whose jurisdiction this comes, has said that Americans are able to and

can do more and better work than any other workmen, and fully pay their

employers for their higher wages and better board. Therefore, it is

again quite pertinent to ask why, on a 10,000-tons deadweight American

steamer, it takes 30% more men than on a similar sized steamer of any

other nation? On a ship of this class the British require two licensed

engineers, where the American requires four; and, in addition to this,

the American requires three oilers and three water tenders. Ordinarily

on foreign ships the storekeeper, donkeyman and a greaser do the work of

the oilers, and no water tenders are carried. In fact, the name of water

tender is unknown. At an investigation of a committee of the House, 1

was asked what the water tender did. I replied he sat on a box in the

fireroom and did nothing but draw his wages and eat his meals.

Now we come to that

clause in the Seamen's Bill which states that 75% of the crew, in each

department, shall be able to understand any order the officers may give.

This prevents

STEAMER "ROBERT DOLLAR" THE THIRD LARGEST CARGO SHIP AFLOAT

American ships from

carrying 75% foreigners who do not understand the English language. This

is intended to prevent the carrying of Chinese crews on American ships,

which it is necessary for us to do if we desire to successfully compete

with the Japanese. But, the Bill does not prevent Japanese ships from

carrying Japanese crews with Japanese officers; hence, another reason

that has been instrumental in placing the Japanese of to day in full

control of the commerce of the Pacific ocean. Another clause to which I

refer provides that 65% of the crew, exclusive of officers and

apprentices, shall be certificated able seamen. This portion of the law

was so impossible of execution and so unreasonable (because the men were

not obtainable), that no notice has been taken of it during the war.

When peace comes, however, it may be enforced, and will result in the

tying up of half of our merchant marine.

Another clause in the

Bill provides that a collector of customs may, on his own motion, and

shall upon the sworn information of any reputable citizen, deny

clearance and hold a ship until an investigation is made. So any

waterfront sorehead can hold up any ship. This is so drastic and vicious

that it also has not been enforced: but it is the law nevertheless.

Another clause provides

that a seaman can demand and shall receive half of the wages he has

earned (note the word "earned''- not "due," as it should be,) at every

port the ship goes to, and every succeeding five days he can make other

demands. This has done more harm to the few American ships that were

left than anything else, as it gave to the men money to keep them in a

drunken state. The police records of various ports where American ships

have gone, especially Shanghai, Kobe and Yokohama, bear ample proof of

the bad effect of this law. The intention of this clause was, to allow

the men to draw their wages and desert; but it did not work that way,

although it causes serious delay to a ship at almost every port. This

must be repealed.

The sailors shall be

divided into two watches. On many ships a big crew is carried and enough

men to navigate the ship are put on "watch and watch." The balance of

the crew sleeps all night and works all day, the object being to get the

day crew to keep the ship in good condition. If this section was

enforced, a ship would have to carry a smaller crew and let the keeping

up of the vessel go, as men cannot do any work at night except that

which is necessary in handling the ship.

This Bill is entitled "to

promote the welfare of American seamen." The inspector's records of San

Francisco, shortly after it became a law, show that of 2064 men, 8% were

American born, 17% naturalized citizens, and 75% were aliens. An

American steamer cleared recently from San Francisco with a crew

composed of three Hollanders, four Greeks, one Swede, two Irishmen,

three Englishmen, one Australian and three Americans. What a joke,

calling them Americans!

The clauses in the Bill

providing for greater safety of life at sea and having better

accommodations for the crew should be retained (except the absurdities

relating to davits and lifeboats on cargo vessels, which have never been

enforced). The American ships built recently have excellent

acommodations and leave nothing more to be desired, and the food served

to American crews is much better than that served on board of ships of

any other nation—in fact, it is as good as I have at my home.

The foregoing are only

the most vicious parts of the Bill, and only a few of the many changes

that must be made to put us on an equality. Other parts of the Bill

against foreign ships will, no doubt, be attended to by foreign nations

after the war.

The President said that

if American shipowners could not operate ships the Government would

operate them. This statement is on a par with tying our hands securely

behind our backs and putting us in the prize ring against an opponent

with both hands free and backed by his government.

The answer to this is,

that American citizens before the war were successfully operating

2,500,000 tons of ships under foreign flags. Those same men would be

only too glad to operate them under the Stars and Stripes if our laws

and regulations would only permit them.

More foreign trade is

conceded to be an absolute necessity after the war; therefore, it is

well to remind the people of the United States that our foreign trade is

so linked with our merchant marine that they cannot he separated. This

is also true of our manufacturing plants, banks, merchants and fanners.

The ramifications of this subject are so great that, directly or

indirectly, they affect every American citizen. Therefore, the time has

come to demand the necessary legislation and regulation to put the

operation of our ships on an exact equality with those of our

competitors. Nothing else will do.

We certainly want some

ordinary common sense injected into our laws. Surely the Government will

see that our useless and oppressive laws and regulations will be

changed, in view of the fact that when the reconstruction period is over

we will have nearly as big a merchant marine as Great Britain. If these

changes are not made, we will see our merchant marine melt away, as

shown in the diagram from 1810 to 1914.

Had a very enjoyable

Sunday on the second of February, 1919, when Grace's son and Stanley's

daughter were baptized in the church at San Rafael. They were named

Alexander Melville Dickson and Diana Dollar respectively.

In April I attended the

meeting of the Foreign Trade Convention in Chicago, and addressed a very

enthusiastic gathering at which about two thousand were present. The

subject was "Our Merchant Marine,"

I arranged to establish

an office in Chicago, the principal object being to solicit and collect

freight for our trans-Pacific steamers. This office has been a success,

so we have considerably enlarged its scope by soliciting freight from

many cities for both Vancouver and New York.

I bought five acres of

land in Oakland for the Occidental Board to be used for the bringing up

and the education of small boys and girls of Chinese parentage. Suitable

buildmgs will be erected in due course. This work is ably carried on

under the direction of Miss Donaldine Cameron.

I was recently elected

president of the Pacific American Steamship Association, and although I

am really overburdened with work, accepted the responsibility as I felt

sure the association would do a good work in getting all the companies

to pull together and present a solid front. This also had the effect of

getting the Shipowners' Association to work in with it so that all the

shipowners now present a solid front to obtain what is right. Then they

both, are working in harmony with the American Steamship Company of New

York, so that all the organizations are working together.

About this time we

decided to purchase some more steamers, so Melville and I went across

the continent from Vancouver to Sydney, Nova Scotia, where the steamer

War Melodv was about to arrive, and we wanted an opportunit to inspect

her. She is a vessel of 10,760 tons deadweight, and came near to our

requirements, so we bought her and renamed her Grace Dollar. While she

is not exactly our style of ship, she has turned out entirely

satisfactory. This I learned by sailing on her for over a month in the

Far East. |