|

CASTLE-DOUGLAS

LITTLE

town, once built at the foot of a hill and ever since running a race up it–I

do not know whether you are very proud of me, but at any rate I am proud of

you.

To me

you are still "the toon "–my town. I came to you as a boy, and found in you

the best of schoolmasters, the best of schoolmates, the snellest,

sharpest-tongued, kindliest-hearted folk in the world. If ever I have

written concerning you that which seemed to make for mirth, the laughter was

noways unkindly. And then, you know, all that I have said of you is

sugar-stick and dropped honey by the side of the reports of your School

Board meetings as given in the "K. A.," which I so faithfully read–in order

to see what the " Raiders" of old said to one another just before they drew

their quarter-staves and fell to the head-breaking.

Causeway end.

I have

spoken with those who remember you altogether at the brae-foot, only

flinging one arm up Little Dublin and another along Marie Street towards the

Loch. You were then that village of Causewayend, which Sheriff Gordon of

Greenlaw, who carted his marIe along that street, says was founded by

himself, and not (as has always been understood) by Sir William Douglas of

Gelston Castle. [See

Chapter xxxii., "A Galloway Laird in the Eighteenth Century."]

In my

own time, life centred about the Cross, and so continued during all my life

as a schoolboy. But ever since, contrary to all the laws of gravitation, the

town has been rushing faster and ever faster up hill, apparently to get a

sniff of the cattle-marts of a Monday, and to see the white smoke of the

trains coming and going about the junction the rest of the week.

But I

Cannot hope to say much wisely of the town as it is. It has grown quite away

from me. However, it contains the best hotel in the south of Scotland, the

Douglas Arms, where the most kindly thoughtfulness has long been

traditional. Here the traveller will find the best of horses to carry him on

a score of interesting excursions, and the best of good cheer to return to

at his day's ending.

Castle-Douglas, which I knew as a village, has grown into the "emporium"

from which the most part of Galloway supplies itself. Its position makes it

a natural centre for the traveller. It has the advantages, as well as the

disadvantages of prosperity. It is neat, clean–a proper town, in every

sense. The houses wear a smiling aspect. They know that they are well built

and able to bring in good. money to the fortunate owners. The shops, though

noways garish, have the look of steady-paying customers and excellent

connections. The churches are large, well filled, well manned, advancing,

zealous in all good works, and, as of old–well able to speak out their

opinions of each other.

The Village that was.

But in spite of all I love the village that was, even more

than the prosperity that is. Still, however, there are links with the

past–my old minister, my oId Sunday School teacher (neither yet old in

years), a companion or two looking out from shop-doors a which I used to see

their fathers and uncles. But once outside the clean bright little town,

always busked like a bride–there the world is as I knew it. The Loch,

indeed, can never have the charm for others it has for me. For I left it in

time. I had no need to grow weary of the quiet glades of the Lovers' Walk,

and the firry solitudes of the Isle Wood. The Fair Isle (my" Belle-lIe-en-Mer

") remains fair as ever for me. On the blackest night of stars I could push

a borrowed canoe (what an optimist was the lender!) through the lily -

studded lanes and backwaters between the Fair Isle and Gelston Burn. Perhaps

the lanes and paths we clove with hatchet and gardening knife, through the

tangled brushwood of the small Isles, exist to this day–perhaps not.

Still woodland glades, peeps of the little town across

glassy stretches of water, a haunting murmur of birds, and the most perfect

solitude to dream and work in-that was the Lovers' Walk. And is, I believe,

unto this day.

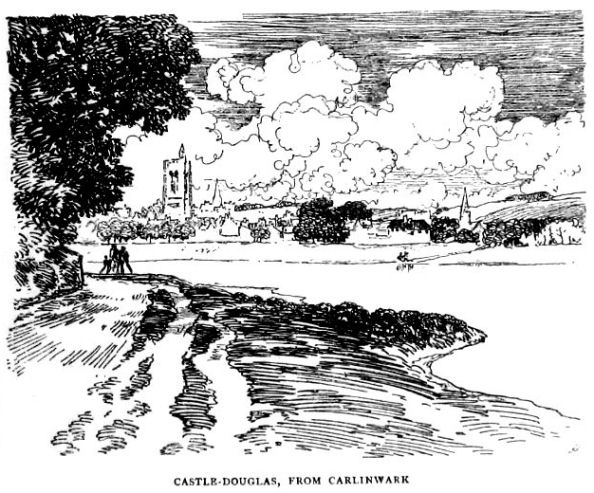

Carlinwark is hardly a loch. I have heard it called a

duck-pond. Well, if so, blessed be the ducks that swim in that pearl of

ponds. I have crossed Ladoga, and seen less of beauty than you may see by

walking open-eyed from the foot of the Lovers' Walk to the Clachan of

Buchan. Open-eyed, I say. For all depends on that.

There was a tree, a silver-birch, which grew upon a point

near the little grassy islet which fronts the Fair Island on its eastern

side. We, the boys of twenty-five years ago, loved it. We sketched it after

the manner of MacWhirter. We wrote odes to it. Mine I even printed. It was

"Our Lady of the Woods." One day it chanced that the wandering trio who did

all these things, came on the fourth youth also regarding the beautiful

white birch. There was a kind of reverent, 'joy

on his

face. Our hearts warmed to the fellow. we had not thought highly of his

mental powers. after all, we were mistaken.

"That's

a bonny tree," he said, seeing us also gazing up at it.

"Yes,"

we cried, rejoicing as the angels do over a soul saved, "we think it is the

loveliest thing all about the loch."

"Aye,"

he said, “I was just thinkin' the same–it wad make grand clog-bottoms!"

He was

a clogger! And, alas, he cast the evil eye on "Our Lady of the Woods." To

clog-bottoms she came at long and last. She was laid low in the great

windstorm of December 1883, just at the time when the dust from the Krakatoa

outburst was reddening the skies of the world. Then I wrote another ode upon

her.

Carlinwark.

Hardly

from anywhere about the streets of Castle-Douglas, and from nowhere that I

know of about Carlinwark Loch, can Thrieve Castle be seen. Yet though

forgotten by the new, Thrieve was once the centre of all the south–one might

almost say of all Scotland.

Go out

by the foot of King Street, and ascending Carlinwark hill, you will soon be

able to look across the bogs and marshy meadows to the grey keep rising out

of the river a couple of miles away. Once on a time the gallantest hearts in

Scotland came riding over these wastes. Across the drawbridge of yonder

castle, and so over this very hill of Carlinwark, they came daily to the

forge of Malise M'Kim, the mighty smith of the Three Thorns.

It is

written of William, ["The

Black Douglas," p. 15. (Smith. Elder & Co.)

] the splendid young sixth Earl of Douglas and

third Duke of Touraine, how "upon his horse Black Darnaway he rode right

into the saffron eye of the sunset. On his left hand Carlinwark and its many

islets burned rich with spring-green foliage, all splashed with the golden

sunset light. Darnaway's well-shod hoofs sent the diamond drops fiying, as,

with obvious pleasure, he trampled through the shallows. Ben Gaim and Screel,

boldly ridged against the southern horizon, stood out in dark amethyst

against the glowing sky of even, but the young rider never so much as turned

his head to look at them.

"Presently, however, he emerged from among the noble lakeside trees, upon a

more open space. Broom and whinblossom clustered yellow and orange beneath

him, garrisoning with their green spears and golden banners every knoll and

scaur. But there were broad spaces of turf here and there on which the

conies fed, or fought terrible battles for the meek ear-twitching does,

"spat-spatting" at each other with their forepaws, and springing into the

air in their mating fury.

"William of Douglas reined up Darnaway underneath the whispering foliage of

a great beech, for all at unawares he had come upon a sight that interested

him more than the noble prospect of the May sunset.

"In the

centre of the golden glade, and with all their faces mistily glorified by

the evening light, he saw a group of little girls, singing and dancing as

they performed some quaint and graceful pageant of childhood.

"Their

young voices came up to him with a wistful, dying fall, and their slow,

graceful movement of the rhythmic dance seemed to affect the young man

strangely. Involuntarily he lifted his close-fitting feathered cap from his

head, and allowed the cool airs to blow against his brow.

",See the robbers passing

by, passing by, passing by,

See the robbers passing by,

My fair lady!'

"The ancient words came up clearly and distinctly, and

softened his heart with the indefinable and exquisite pathos of the refrain

whenever it is sung by the sweet voices of children.

" 'These are surely but cottars' bairns,' he said, smiling

a little at his own intensity of feeling, 'but they sing like little angels.

I dare say my sweetheart Magdalen is amongst them.'

"And he sat still listening, patting Black Darnaway mean·

while on the neck.

" ' What did the robbers do

to you, do to you, do to you,

What did the robbers do to

you, My fair lady!'

"The first two lines rang out bold and clear. Then again

the wistfulness of the refrain played upon his heart as if it had been an

instrument of strings, till the tears came into his eyes at the wondrous

sorrow and yearning with which one voice, the sweetest and purest of all,

replied, singing quite alone:

" 'They broke my lock and

stole my gold,

stole my gold, stole my

gold, My fair lady! '

"But the young earl, recovering himself, soon found what he

had come to seek. Malise Kim, who by the common voice was well named 'The

Brawny,' sat in the wicker chair before his door, overlooking the

island-studded, fairy-like loch of Carlinwark. In the smithy across the

green bare-trodden road, two of his elder sons were still hammering at some

armour of choice. But it was a ploy of their own, which they desired to

finish that they might go trig and point-device to the earl's weapon-showing

to-morrow on the braes of Balmaghie. Sholto and Laurence were the names of

the two who clanged the ringing steel and blew the smooth-handled bellows of

rough-tanned hide, which wheezed and puffed as the fire roared up deep and

red, before sinking to the right welding-heat, in a little flame round the

buckle-tache of the girdle-brace they were working on."

A little farther along the Carlinwark road, and you will

come to the outlet of the canal, which was constructed to convey Sheriff

Gordon's marIe to the sea (v. chap. xxxii., "An Eighteenth Century Galloway

Laird"). You would never imagine that it was made to carry field manure.

Clear and slumberous under its great trees it glides away, stray lights upon

it dancing through the leaves, till it emerges upon the wide moss of

Carlinwark, and becomes, at once congested and stagnant. Still, occasionally

in winter, one may see, upon some day of high flood in the river Dee, that

peaceful canal pour a red and ridgy torrent into the loch, raising it in a

few hours to the level of the road, putting half the islands under water,

and altering the whole face of nature. I remember one joyous September

fair-day, some thirty years ago, which we spent entirely in boats among the

trees of the Isle Wood, discovering new continents, rescuing distressed

damsels, and generally Crusoe-ing it to our hearts' content.

The hamlet of Buchan.

One must not leave behind the hamlet of Buchan with only a

passing glance. It sits right picturesquely in a nook of the woods-the loch

in front, Screel and Bengairn in the distance, though, l fancy, invisible

save from the water's edge.

Then comes the Furbar, one of the oldest farms in Galloway,

but to me memorable chiefly because two small boys in the later sixties used

to carry milk therefrom to their respective families. The time it was

winter. The mornings were cold. Throwing stones into the loch to break the

ice was an agreeable youthful pastime. So one boy left his can by the

roadside, while the other more prudently kept his by him as he threw. But on

going back, the first can aforesaid, with the entire day's milk of a

respectable family–was gone! Number One's father had passed on his morning

walk-and taken the can home with him I It may well be believed that Number

One had certain experiences when he appeared canless and milk less in his

ancestral halls. For a long time afterwards he manifested a curious

preference for a standing posture. But there was obviously a mystery

somewhere which has never been quite cleared up. |