|

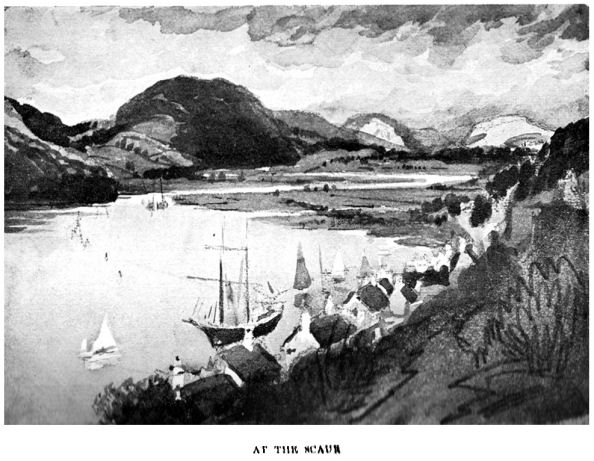

DALBEATTIE

THE little Town of Granite has seen many vicissitudes in

its short life. Time was and may be again when all about Craignair, and far

along the road towards Barnbarroch, the sound of the blasting shot was

continually heard. The quarries roared with traffic. River craft could not

carry away the "setts" fast enough to pave the streets of Liverpool.

Houses–lodgings even–were not to be got, and quarrymen slept in rude

shelters and bothies beside their tools.

The Towne Granite.

Then again Dalbeattie was almost as a City of the Dead–very

like one indeed, with its tall granite columns, rising here and there in the

half-deserted polishing works–tombstones made on "spec," waiting for the day

when some notability would die, and a fulsome inscription be cut upon that

smooth tablet. Now in the granite town there is a pleasant

betwixt-and-between of prosperity, "neither poverty nor riches" so desired

of the Psalmist, however unwelcome to the stirring man of affairs.

There is not much to see in Dalbeattie itself, except one

of the cleanest and most pleasant little towns in Scotland, a navigable

river, very like a Dutch canal, a ridgy hill which from a distance seems to

have exploded volcanically, like Krakatoa or the Japanese Bandai-san. There

are, however, many pleasant walks, wooded and quiet. Above all there is an

admirable hazel-wood a little way along the line-side towards

Castle-Douglas. The nuts are ripe about the time of the Castle-Douglas

September Fair, and you will probably be chased out by the keepers. Only on

one occasion did.

I quite escape their vigilance. The best way is to run for

the railway line, get over the fence and make faces at them. If the

surfacemen inquire who you are, remember to say that you are the son (or

other immediate relative) of the Traffic Superintendent. These very

practical points are added in order to increase the usefulness of the book.

Mr. William Maxwell, of the Glasgow Scotsman office, will bear me witness

that they proved most valuable in our time. Thus from generation to

generation pearls of information are passed on. And if we seniors can add to

their happiness by a little thing like that, the rising generation will

surely call us blessed.

Be sure, however, that you can run faster than the keeper.

This is most important.

Northward again, you have the Urr, a pooly, trouty,

rippling, unexpected sort of a stream, half a bum grown up, half a river

grown small. If you care for fishing, as I do not (save in connection with

the frying-pan) you will find fish therein. They run small, or rather did

thirty years ago. But you can generally catch them with the fat stubbly ones

which you find under flat stones at the back of the cow-house. It is best to

go very early in the morning, and have a good many spare hooks along your

line, getting home before breakfast time, so as to avoid remark. Any further

information can be obtained from my friend Andrew Clark Penman of Dumfries.

If you start about 3 A.M. and get back for breakfast, it is not night

poaching, and you get off with a reprimand. It is unnecessary to carry a

fishing-basket. A pair of deep side pockets to your coat-inside-will be

found to be much more useful. If you use a net, always take out the little

thorn bushes which the keepers put in the bottoms of the pools. This shows

carefulness on your part, and gives the poor labouring man something to do

the next day.

There is also a sport called fly-fishing, but Penman and I

don't know anything about that. All our offences are long since covered by

the Statute of Limitations.

Then within a morning's walk of Dalbeattie there is the

Cloak Moss, a famous place for wild birds' eggs. With a

little care you need never be hungry there between the middle of March in a

good year and the end of June. The method of cookery is simple. First you

find your nest–plover, curlew, snipe, according to your luck. Then you

ascertain (by trial) whether the egg is fresh. Then–but what comes after

that the reader must find out for himself, and afterwards teach it to his

grandmother.

A Feathered Wager.

It was among the wild, bouldery fastnesses at the back of

the Cloak Moss that a certain bet was settled, on the way to Tarkirra, that

remarkable hostelry, of which all trace has long since passed away from off

the face of the moorlands.

It is worth while, however, ascending the wild benty

hillside of Barclosh, and so over the trembling green bogs of the Knock

Burn, to see "where the grey granite lies thickest," even though no more

does the reek of any unlicensed "kiln," or whiskey-still, steal up the face

of the precipice, mingling faintly blue with the heather and bent.

The wager about which kind of bird a pair of travellers

will see the most of, was really tried on the Colvend shore road one

pleasant May morning when all the feathered folk were busy about their

affairs, and with the exact result indicated below. It is a game which two

can always play, and has been found to lighten a long weary road

wonderfully–next best, indeed, to the telling of tales, or (so I am

informed) the making of love.

Here is the incident as related in "The Dark 0' the Moon"1:-–

" 'Settle it, Maxwell Heron,' he cried, making his pony

passage and champ the bit as it was his pride to do. (He was practising to

show off before the schoolmaster's Toinette, as tricksome a minx as ever

Birted a Spanish fan.) 'Maxwell Heron, you never had the instinct of a right

gentleman in ye, man. Here are five silver shillings–cover them wi' other

five. There ye are! Now, what bird that flies the air, think

1

Macmillan & Co.

ye, will we see the oftenest between here and Barnbarroch

Mill Wood? "The shilfy" (chaffinch), says you. Then, to counter you, and

bring the wager to the touch–I'm great wi' the black coats–I'll e'en risk my

siller on the craw.1 He's the Mess John amang a' the birds o' the

air! '

"So we rode along in keen emulation, and as we went I made

a list of the birds we encountered. When there was no doubt, and we both

agreed, I pricked a mark after the name of each we saw. At the Faulds of the

Nitwood the mavis led by a neck from my friend the 'shilfy.' But there, as

ill-luck would have it, we encountered a cloud of rooks making merry about a

craw-bogle which had been set up to scare them off some newly-sown land.

Jasper shouted loud and long. The siller, he maintained, was already his. I

had as lief hand it over. I told him to bide a wee–all was not over yet.

"Now, I began to remark, that while the chaffinch and the

sparrow, the robin, and his swarthy rookship occurred in packs and knots and

clusters, there was one bird which had to be pricked off regularly and

frequently. This was the swift (or black swallow). Whether it was that his

long elastic wings and smooth swoopings brought the same bird more than once

across our vision, or simply because every barn and outhouse sheltered a

couple, it was not long before it was evident that both Jasper and I had

small chance of heading the poll with our favourites. By the time we had

gotten to the Moss of the Little Cloak, and left the woodlands behind us for

that time, the prickings of my pencil had totalled as follows ;– The swift

(or black swallow), 74 ticks; the chaffinch or shilfy, 46 ticks; the cushy

doo or wood pigeon, 38 ticks; the craw or field rook, 37 ticks; the magpie,

23 ticks; the mavis, 19 ticks. And this, though mightily uninteresting to

most folk that read or hear tales, is yet of value. For it tells what birds

were most plentiful in our Galloway woodlands on a certain May morning in

the year of grace 17–."

And so, having settled this matter, the travellers went on

by the wild benty hillside of Barclosh, and over the trembling

1

Craw: used in the south of Scotland or the rook.

green bogs of the Knock Burn, straight as an arrow for

Tarkirra, that curiously-named place of public entertainment among the

muirlands, "where the grey granite boulders lie thickest, and the reek of

the unlicensed 'kiln' steals most frequently up the face of the precipice." |