|

CHAPTER VI

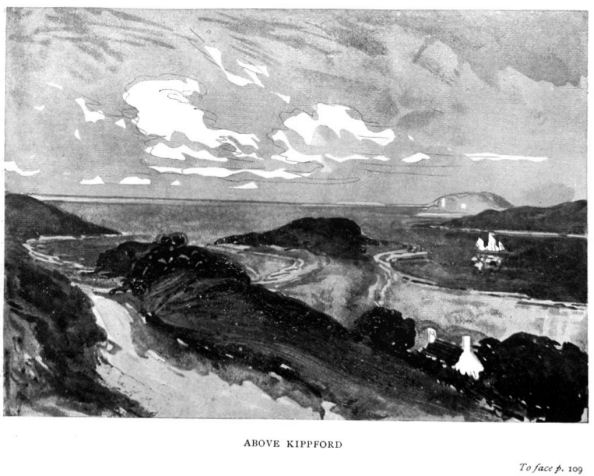

COLVEND

"THE

RIDDLINGS OF CREATION"

THE Hinterland of this

Paradise of cave and arch and grotto is the parish of Colvend, or as the

Galloway folk like to say. lovingly softening their voices to the sound of a

dove cooing (even as Patrick Heron heard them), "Co'en "–they call it “the

Co'en shore" quite forgetting the big wild parish which lies behind that

narrow fringe of white foam and blue sea.

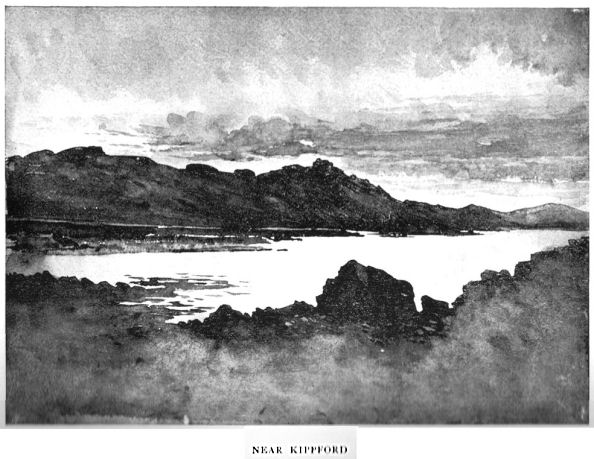

High on Criffel.

The last time I set eyes

on Colvend (this seaboard parish which looks across to Cumberland) was when,

dreaming over the writing of "The Raiders," I stood alone on the hoary scalp

of Criffel. The whaups circled about me as I looked towards the more fertile

holms of the North.

"Troqueer! " they cried, "Troqueer!,

Troqueer! We were better there than here." And yet I am not sure that the

whaups were right. For nobler is the wild red deer of the mountains, braying

his challenge from hilltop to hIlltop through the mist, than the lowing of

myriads of kine knee-deep in fat pasture-lands.

As I stood thus,

correcting my boyish memories of twenty years before, the phrase which

stands at the head of this chapter rose into my mind–" The Riddlings of

Creation."

"That's it," said I; "the

very thing."

Other places and parishes

have been so called, I know, but here in Co'en surely the Almighty made a

bigger bing and used a wider mesh to His riddle. Some indeed there be who

say that here the "boddom fell oot o' the wecht a'thegither!" Whether they

are right or no, I cannot say.

There is, for example,

Minnigalf–crowned king of all the moor parishes of Galloway, and, as I

think, of Scotland. There is, truth to tell, routh of "riddlings" in

Minnigalf. Yet Kells also runs it hard. Girthon is green with bracken and

purple with heather for many a mile, but for varied wildness and a certain

saucy defiance, characteristic also of its maidens, Co'en cowes them at.

Bourtree Buss.

I cannot, indeed, write

about Colvend, or indeed about any of the "Ten Parishes" east of the Water

of Urr, as I can of my own country, being by birth and breeding a lad of the

Dee. But for five or six years it was my lot to spend a considerable part of

every summer there. I stayed sometimes at the house of a distant family

connection, who was the farmer of a place which I shall call the Bourtree

Buss. Robert Armstrong (that was not his name either) was already an old man

when I knew him, but he was still fresh and hearty, with a stalwart family

scattered allover the world. His wife was master, however–a tall, gaunt

woman, apparently clothed in old com sacks, and with a poke bonnet you could

have stabled a horse in–a woman terrible to me as Fate. For in those days,

strange as it may seem now, I had in me not infrequently the conscience of

an evil-doer.

"Sic a laddie for earin'

as I never saw. The only thing he has nae stammock for, that I ken o'–is

wark."

This was spoken of one of

her own grandsons, my companion, hut I knew well that I was under the same

ban. I shall not soon forget how she used to roust us out of our warm beds

about half-past four in the morning, and set us to carry water from the

well–"to give us an appetite." She need not have troubled.

"Are ye weel?" she would

say in a pipe like that of a boatswain, at the foot of the stable ladder.

"Aye."

" Then rise."

That she "likit the beds

made an' a' things trig by breakfast-time" was a favourite phrase of hers.

At Bourtree Buss breakfast was at six, dinner at twelve, so there was plenty

of time between to "fin' the grunds o' your stammock." By noon that organ

seemed as vast and as empty as the blue vault of heaven.

The guidman used to lend

me his great three-decker spyglass with" Dollond, 1771, London," engraved on

it in quaint italics, cautioning me to "slip oot at the back and no let the

mistress see ye. She disna like things ta'en frae 'boot the hoose."

Then, it is sad to have to

relate, if by any process whatsoever, not excluding actual breach of the

eighth commandment, we could obtain a "soda scone" or two, and a whang of

cheese, we were supremely happy. The reader may, he very sure that, having

located the "auld woman," we kept the bieldy side of a dyke till well out of

her reach.

More than once, however,

the mistress of Bourtree Buss caught us redhanded, when, as a natural

consequence, the sides of our heads rang for ten minutes.

Nevertheless her bark was

a good deal worse then her bite, for I never remember that she took the

stolen provender away from us.

"Be guid bairns," was ever

her parting salute, "and dinna bide awa' late, haein' us seekin' the hill

for ye, an' thinkin' ye hae faten over the heuchs aboot the Coo's Snoot! "

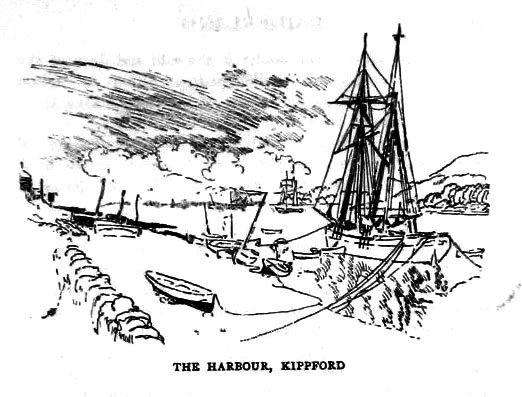

Once free of the farm

buildings and across the narrow crofts, we came out suddenly upon the great

heathery hill-sides, or we went farther afield til we would find ourselves

among the tall headlands, with the wind whistling in our teeth and the

telescope laid accurately on some sloop or schooner beating up the Solway or

making a long tack to avoid the deadly pea-soup of Bamhourie Sands, while

above we watched the mists lift off the Cumberland hills.

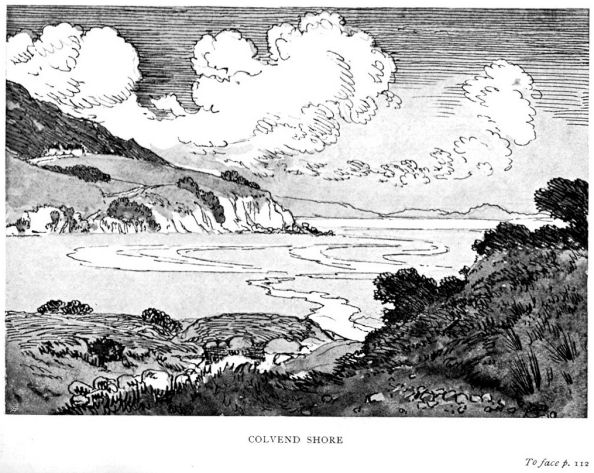

The whole coast grew

familiar to me in those warm days of highest summer. I cannot remember ever

having been tired. Yet from the heuchs above Port-o'-Warren, I can recall

walking as far as Sattemess and back in a day, no doubt ranging all the time

up hill and down dale like a questing collie, and making the road three

times as long as it need have been. We had, of course, no stiver of silver

in any of our pockets, but that was no "newance." We had still, however,

some" mullins" in our jacket" pooches "–and we discovered that soorocks to

suck are but a moderate relief when one is hungry.

On the beach of the Scaur

we found a gruff-looking old salt painting a boat, and, boy-like, fell into

talk with him. He called us, I remember, "idle, regairdless loons," and

asked us if we had ever done a good honest day's work in our lives.

"If he had us on his boat

he would learn us to gillravage athort the kintra screevin' the verra soles

off our boots! ..

Then after this prelude he

commanded us to follow him. We did follow, as it were, afar off, for we knew

not to what fate he was conducting us. It might be to durance vile as

vagrants, or even to the rope's end he had so frequently promised us.

But the kindly tar only

threw open his cottage door with a "Hey, guidwife, here's twa lads that hat

walkit frae the Bourtree Buss ower the Heuchs. Hae ye ocht ye can gie them

to fill their kytes?"

Captain Wullie.

Ah, good Captain Wullie o'

the Scaur–I ken not whether ye be in the land of the living or wandering in

the shades of the dead. But if the latter, I pray that some kind spirit may

meet you by the way and throw open as friendly a door and as handsomely

welcome you in to eternal light and rest.

Mostly, however, it was to

the deep gullet of Port-o'-Warren and the wider surf-beaten rift of Portling

that we confined ourselves. And though I have not set eyes on either of

these for five and twenty years, I can see in my mind's eye every turn and

twist of the coast-line, every clean-bitten gap in the brown rocks, every

tangle of green weed and purple tress of dulse between Port-o'-Warren and

Douglas Hall. And if there be finer and more varied coast scenery within

the same space anywhere, I, for one, have yet to see it. The dancing sea–out

and in of which we were all day dipping like gulls, never very wet and never

very dry–the white towns of the English North Country with their smoke

blowing out over the Solway, the hoarse roar of the tide swiftly covering

the Satterness Sands, the clean, hard beaches at the Needle's E'e and the

Piper's Cove, these are worth many provinces in Cathay–to me, at least, as a

Gallovidian and a romancer.

Of the black deeps of the

Piper's Cove I have a tale to tell. Once upon a day my co-rapscallion and I,

questing from Bourtree Buss, entered it. Brave was not the word for us–we

were heroes. Others had been "feared." We would never be. It was all

nonsense about the devil being up there. Ghosts did not exist, We would show

them if they meddled us.

Cautiously, and hand in

hand, we advanced.

Soon after we had left the

light behind us, and the walls had closed in solid as the centre of the

earth, Rob thought he heard a noise.

" Only the water," said I

to reassure him.

"Suppose the tide comes in

in a hurry!" he suggested, " it micht be that."

I laughed at the idea. The

tide only came in once in twelve hours, half-an-hour later each time. It

said so in the geography, or at least something like that.

But, all the same, there

was a sound–a low,heart-chilling murmur–and it was decidedly growing louder

as we advanced .

"Strike a match!" cried

Rob.

We bad been keeping these

for the inner depths of the cave, but all plans must give way in the face of

imminent danger.

The first one sputtered

and went out.

The second showed all too

plainly the veritable lineaments of Satan: burning eyes, black facet horns

and all–yes, horns black and curly.

At the sight of the light

something flew at us with a hoarse grunt.

The match went out, and my

companion rushed past me down the passage, crying out with all his might,

"It's him! It's the de'il! If I win aff this time, as sure as daith I'll

never steal my granny's sody-scones again."

Yet, after all, it was no

more than a black-faced "tip" which had wandered down from the heuchs and

had got tangled and bemazed in the cave-mouth. I rallied my comrade bravely

on his terror–though, Heaven knows, I was as frightened as ever he could

have been.

"Did ye think I was feart?"

Bob asked in great indignation.. "Man, I was juist lead in' him oot to get a

whack at him in the open."

It will be no astonishment

to those who read this story that my early friend of the Piper's Cove

succeeded in business. There is nothing like having an excuse ready.

It was long after this

day, when I was a lad of fifteen, that I spent two of the happiest months of

my life at Roughfirth with the only thorough comrade I have ever had. Our

paths have diverged very wide and far, but I doubt not at the day's ending

we shall meet again at the braefoot, and stroll

quietly home together in the

gloaming as we used to do of yore. Loyal, generous, brave, open· hearted

Andrew-not many had such a friendt and what he was then he is

today.

The story of our

adventures (with some additions) you may read in the island chapters of "The

Raiders." Even thus we lived and fought and "dooked," and made incursions

and excursions in search of provisions–being chronically "on the rocks,"

alike for the sinews of war and as to a daily supply of the staff of life.

" With additions," say I.

Yes, and with "substractions" too, as we used to call them at school. For I

have another confession to make. In the interests of art I deliberately

libelled a good and kind friend. It was not May Mischief who brought us the

noble beef-steak pie to Isle Rathan–though there were two or three girl

cousins not far off, as mischievous and almost as pretty as May. (I wonder

if certain staid mothers of families remember how they and we used to race

down Mark Hill behind the little hamlet of Roughfirth, which was then our

temporary home! But this is a manifest digression.)

A Friend in Need.

It was not May Mischief, I

say, who brought us the pie. It was my friend's lady mother, who, in the

hour of our need, one sad Saturday when our credit was completely exhausted

at the "shop," brought us the delight her bonny face and comfortable figure,

and–what I regret to say seemed even better–the noblest pie that hungry

teeth ever crumped the paste of.

Nor did she pursue us all

over the Isle with threats and alarms of war. On the contrary, she sat down

on a chair and said, with her hands on her knees–

"Oh, that waggonette! I

declare, I'm a' shooken sindry! Noo, hoo muckle siller can ye laddies be

doin' wi'? "

Andrew and I looked at each

other. We could have "dune" with about a hundred pounds, but we compromised

for thirty shillings. Even this was a stretch.

"And I dinna ken what I'll

say to your faither when I get hame!" she said as she handed over the

dollars.

Blessed thought, we were

solvent again, and could look even the "shop" in the face!

Good friend and kind,

across the years I salute you. Your "other son" has not forgotten you, and

hereby sends his love to you, and makes his all too belated apology.

|