|

THE RAIDERS' COUNTRY

I.-WHY WE ARE WHAT WE ARE

Between Dee and Cree.

BETWEEN Dee and Cree–that

is our Ganaway. A link of Forth were almost worth it all. The uninstructed

conceives of Galloway as but a parish somewhere in broad and Scotland. To

the native it is–as its wild Picts were in the national line of battle–the

very vanguard of empire.

When we meet each other

far over seas, or even in such outlandish parts as Edinburgh, to be of

Galloway warms our hearts to one another, and not unfrequently, perhaps,

uncorks the "greybeard." But when we of one part of that wide province meet

one another down in Galloway itself we are a little apt to walk round each

other, and growl and snarl like angry stranger curs at one another's heels.

For to the man from the Rhynns, the man from the East Side that looks on

Nith is but a border thief. And with regard to a man from Dumfries itself,

the question is not whether any good can come out of such a Nazareth, but

rather whether any evil can come out of anywhere else.

Enemy's Country.

However, we are forgetting

Ayrshire. To belong to Dumfries is indeed a crime in the eyes of every true

son of the ancient and independent province. But yet there is a kind of pity

attached to the ignoble fact, as for men who would have helped the matter if

they had been consulted in time, but who now have to face the fault of their

parents as best they may.

The case is, however,

entirely different with an Ayrshireman. He is an Ayrshireman by intent. For

him there can be no excuse. For his villainy no palliation. Is there not in

the records of Scottish law a well-authenticated case in which one Mossman

was hanged on May 20, 1785, upon the following indictment ;–

1. That the prisoner was

found on the king's highway without cause.

2. That he "wandered in

his discoorse."

3. "That he belonged to

Carrick."

The last count was proven

and was fatal to him. And with good reason. Many an honester man has been

hanged for less.

I remember a very

intelligent old native of Kirkcudbright telling me that the reception of

Burns's poems in Galloway was much retarded by the prejudice against an

Ayrshireman, and was indeed never completely overcome during the poet's

lifetime.

The Rest of the World.

Other parts of the country

were little regarded by the true sons of Stewartry and Shire. There were

known to be such districts as "Lanerickshire and the wild

Heelants," but they were ill

thought of. People who said that they had been there were looked on "a

thocht agley," as we might look at one who, with no record for conspicuous

daring, asserted that he had been

to the summit of Mount Everest Accounts of their travels were received with

conspicuous and almost insulting unbelief. "Oh, ye hae been in the Heelants,

say ye?" “Ow, aye,–umpha–aye!"

Edinburgh was known, of course. It was a bad

place, Edinburgh. A Gallowayman only went there once. The place he visited

was the Grassmarket, where the king's representative presented him with the

loan of a long tow-rope for half-an-hour.

So that though most of the Galloway lairds of

any degree of respectability in the olden times had had their little bit of

trouble in the days before the Union, most of them preferred to be "put to

the horn" (that is, proclaimed rebel and traitor to the realm and the king's

majesty by three blasts upon the horn at the Cross of Edinburgh), rather

than come up and risk getting their necks mixed up with the" King's tow."

It was a very far cry to Cruggleton and a

farther to the Dungeon of Buchan, and the region of Galloway was not healthy

for king's messengers. The enteric disease called "six inch 0' cauld steel

in the wame 0' him" was extraordinarily prevalent in the district, and

anyone who was known to carry the king's writ or warrant about his person

was almost certain to suffer from it.

It was told of Kennedy of Bargany that on one

occasion his man John had cruelly assaulted an innocent traveller upon the

highway, and was brought before the Sheriff Court at Wigton for the offence.

Bargany appeared to defend his man, and his plea of innocence on behalf of

John was that the man assaulted "Iookit like a Sheriff's offisher or a

lawvyer." John got off.

"Omnis Gallia."

All Galloway is divided into three parts-the

Stewartry, the Shire, and the parish of Balmaghie. Some have tried to do

without the latter division, but their very ill-success has proved their

error. The parish of Balmaghie is the Cor Cordium of Galloway. It is the

central parish–the citadel of Gallovidian prejudices. It was the proud

sanctuary of the reivers of the low country

before the Reformation. Then

it became the headquarters of the High Westland Whigs in the stirring times

that sent Davie Crook back to watch the king's forces on the English border.

From its Clachanpluck every single man marched away to Rullion Green, very

few returning from the dowsing they got on Pentland side from grim

long-bearded Dalyell. It was the parish that for many years defied,

indiscriminately, law courts and Church courts, and kept Macmillan, the

first minister of the Cameronian Societies, in enjoyment of kirk, glebe, and

manse in spite of the invasion of the emissaries of Court of Session and the

fulminations of the Erastian Presbytery of Kirkcudbright.

Balmaghie was a great

place for religious excitement in the old days–though, as one of the

historians of the county says, it is remarkable with what calmness the

people of Balmaghie have taken the matter since.

The adjoining parts of

Galloway–the Stewartry and the Shire–are important enough in their way. They

cannot all be Balmaghies, but they do very well. The Stewartry was in

ancient time the more important of these two larger divisions. Its rental

and taxable value were to the Shire in the proportion of nine to five.

But, strangely enough, it

was not proud of the fact, and has often since tried to get the valuation

reduced. This shows how little conceit of themselves Stewartry men have. If

you want to see real conceit you must go to the neighbourhood of Glenluce,

and ask who makes the best bee-skeps in Scotland.

The Eighteenth Century in

Galloway.

Now a word as to time. The

eighteenth century did not begin in 1701 according to the received opinion.

It really began with William of Orange coming over from The Holland in the

year of the" glorious revolution," and settling the country down into that

smug respectability which for a good while played havoc with the old

picturesque interest. Yet in Galloway there always remained elements of

special interest, owing to the remote and independent nature of the country.

On the other hand, it was

Walter Scott who put an end to the eighteenth century. The Waverley Novels

were a great civiliser, and by making the old world the world of literature,

Scott convinced people in Scotland that they were living in modern times–for

many had lived contentedly all their lives and never known it. They were as

surprised to hear it as M. Jourdain was when he found out that for a long

season he had been talking prose.

"Guy Mannering" was the

instrument by which Scott cultivated Galloway out of the eighteenth century.

Yet the local colour of the book is slight, and to a born Gallovidian hardly

recognisable. For Scott did not know Galloway. He got Galloway legends from

Joseph Train, that careful and most excellent literary jackal; but he

dressed them up in the attire of Ettrick Forest. He thinks, for instance,

that the hills of Galloway are smooth, green-breasted swells, like Eildon or

Tinto; and there is nothing to show that he even suspected what fastnesses

lie hid from the ken of the ordinary romancer and topographer about the

Dungeon of Buchan and Loch Enoch.

So in this wide field of

the eighteenth century it is not easy to give a general idea of how the

people of the double province lived. There was indeed a great advance in all

the comforts of living in Galloway during the eighteenth century-though not

so great, perhaps, as during the nineteenth.

The Old Names.

The ancient gentry of

Galloway, of true Galloway blood, were never a very numerous race, and some

of the greatest names were extinct long before the eighteenth century. The

Douglasses, of course, the greatest of all, had had neither art or part in

Galloway since the fifteenth century. The great house of the Kennedies of

Cassilis had retired upon Ayrshire. Gone were the days when

"Frae Wigton to the toun 0'

Ayr,

Ao' laigh doon by tbe

cruives 0' Cree,

Nae man may howp a lodging

there

Unless be coort wi'

Kennedy."

But in the eighteenth

century there were still Agnews in Lochnaw as there are to this day,

Stewarts in Garlies, MacDowalis in Garthland, M'Kies in Myrtoun and in

Barrower, Maxwells in

Mochrum and Monreith, and of course there were the great politicians of the

time–the Dalrymples of Stair in the old Cassilis stronghold of Castle

Kennedy.

In the upper Stewartry the

well-known names were those of the Gordons of Lochinvar and Kenmure–of

Earlstoun, and of Culvennan. On the Dumfries Marches the Maxwells held sway,

and the Murrays of Broughton were rapidly acquiring land in the south.

The baronage were mostly

content to Iive quietly on their estates in a kind of "bien" hospitality and

good-fellowship. One of the big houses could account for a sheep a week,

besides many pigs and an odd "nowt beast" or two in the "back end." But even

in the great houses porridge and milk and homely oatcake were still the

commonest of fare. We find, for instance, a Galloway soldier of

Marlborough's mourning in a far land that in these outlandish parts they had

neither "farle of cake," nor yet a "girdle" to bake it on. The great houses

were mostly defenced, and such were the exigencies of the time that sieges

were not unknown–the gipsies and outlaw clans of the hills making no scruple

to come down, "boding in fear of weir," and to assault any man's house

against whom they had a grudge.

The position of many of

these Galloway gentry was little different from that of a feudal baron. In

the seventeenth century two and three "merklands" were still granted to

likely young fellows who would settle down on the estates of a knight, under

pledge to be his men and breed lusty loons to wear the leathern jack, and

ride behind him when he went to leave his card on a brother baron with whom

he might have a difference. This, says Sir Andrew Agnew of Lochnaw, in his

excellent " Hereditary Sheriffs of Galloway," is the origin of the phrase–

"Ye are but a bow '

meal-Gordon."

This was a telling sarcasm

against undue pretensions to pedigree, based on a tradition that a Gordon of

Lochinvar and Kenmure, anxious to increase his vassalage, gave any

likely-looking young fellow willing to take his name at least three acres

and a cow–together with a boll of meal yearly. From which it will be seen

that the supposed Radical innovation of "three acres and a cow," used as a

bribe, was really feudal in origin, and began, as many wise and good things

did, in the province of Galloway.

Still this was a better

custom than the charge which is enshrined in another Galloway story; "Ye gat

the price 0' it where the Ayrshireman gat the coo." The admirable Trotter

has the story thus: “There was a queer craitur that they caa Tam Rabinson

leeved at Wigton, and he had a kind 0' weakness; but he had some clever

sayings for all that. Also, like most Gallowaymen, he disliked the

Ayrshiremen for what he considered their meanness and their undoubted habit

of taking people's farms over their heads. One day Tam found a very big

mushroom, and was taking it home to his mother. So when he came to the

corner end, a lot of men were standing about, and a big Ayrshire dealer of

the name of Cochrane among them that had the habit of tormenting Tam, and

trying to make a fool of him. Seeing Tam with the big mushroom, Cochrane

cried out:

" 'Hullo, Tammock, what

did you pay for the new bannet? '

" 'The same price that the

Ayrshireman payed for the coo,' says Tam.

" 'An' what did he pay for

the coo?' asks Cochrane.

" 'Oh, naething! ' says

Tam, 'he juist fand it in a field I' "

Which was a saying

exceedingly hard for an Ayrshireman and a cattle-dealer to stomach.

The Bonnet Lairds.

The bonnet lairds were a

well-known class in Galloway, and were mostly the sternest and most

unbending of Whigs. They were reared exactly like the ordinary farmers, but

their farms belonged to themselves, though a certain service was given to

some of the great barons in return for steadfast protection. Some of these

rose to considerable honour. For instance, there was Grierson of Bargatton,

in Balmaghie, who on more than one occasion was returned to Parliament as

one of the representatives of the Stewartry.

The bonnet lairds lived

much as the better farmers did, but in some things they stood aloof. For one

thing, they locked their doors at night, which no farmer body was said to do

in all Galloway during the eighteenth century. They lived in the summer time

and in the winter alike on porridge and milk, flavoured with occasional

fries of ham from the fat "gussie " that had run about the doors the year

before. Sometimes they salted down a "mart" for the winter, and there was

generally a ham or two of "braxy" sheep hanging to the joists. Puddings,

both white and black, were supposed to be an article of dainty fare.

Sometimes the country folk

did not wait till the unfortunate animal was dead in order to provide

entertainment for their guests.

"Saunders, rin, man, and

blood the soo–here's the minister gettin' ower the dyke!" was the

exclamation of a Galloway goodwife on the occasion of a ministerial

visitation.

It is told of the famous

Seceder minister, Walter Dunlop, of Dumfries, that he too loved good

entertainment when he went out on his parochial visitations.

Specially he liked a "tousy

tea "–that is, one with trimmings.

On one occasion he had to

baptize a bairn in a certain house, and there they offered him his tea–a

plain tea–before he began.

This was not at all to

Walter's liking. He had other ideas, after walking so far over the heather.

"Na, na, guidwife," he

said, " I'll do my work first–edification afore gustation. Juist pit ye on

the pan, an' when I hear the ham skirling, I'll ken it's time to draw to a

conclusion."

"But and Ben" with the Cow.

In the early part of the

eighteenth century the common people of Galloway lived in the utmost

simplicity–if it be simplicity to live but and ben with the cow. In many of

the smaller houses there was no division between the part of the dwelling

used for the family and that occupied by Crummie the cow, and Gussie the

pig.

But things rapidly

improved, and by 1750 there was hardly such a dwelling to be found in the

eastern part of Galloway. The windows in a house of this class were usually

two in number and wholly without glass. They were stopped up with a wooden

board according to the direction from

which the wind blew. The

smoke hung in dense masses about the roof of the "auld clay biggin'," and,

in lieu of a chimney, found its way occasionally out at the door. But many

of the people who lived in these little houses fared surprisingly well. The

sons were "braw lads" and the daughters "sonsy queans." They could dress

well upon occasion, and we are told in wonder by a southern visitant that it

is no uncommon thing to see a perfectly well-dressed man in a good plaid or

cloak come out of a hovel like an outhouse.

"The clartier the cosier"

was, we fear, a Galloway maxim which was held in good repute even in the

earlier part of the eighteenth century among a considerable section of the

common folk.

Later, however, the small

farmers became exceedingly particular both as to cleanliness in food and

attention to their persons. We saw recently the dress worn to kirk and

market by a Galloway small farmer about 1790. It consisted of a broad blue

Kilmarnock bonnet, checked at the brim with red and white; a blue coat of

rough woollen, cut like a dresscoat of to-day, save that it was made to

button with large silver buttons; a red velvet waistcoat, with long flaps in

front; corded knee-breeches, rig-and-fur stockings, and buckled shoes

completed the attire of the douce and sonsy Cameronian farmer when he went

a-wooing in his own sober, determined, and, no doubt, ultimately successful

way.

Galloway Ministry.

I have yet to speak of the

"ministry of the Word" and of the state of religion. Things were not very

bright in Galloway at the beginning of the eighteenth century.

We hear, for instance, of

a majority of a local Presbytery being under such famas that the Synod had

to take the matter up; and in several of the parishes of Galloway the manse

was by no means a centre of light and good example.

This was perhaps owing to

the state of the country after the Killing Time and the Revolution. Many of

the people of Galloway would not for long accept the ministrations of the

The Cameronians.

regular parish clergy, who

were ready to hold fellowship with "malignants." The Society men, Cameronian

and other, held aloof, and though, till the sentence of deposition was

pronounced against Mr. Macmillan of Balmaghie, they had no regular ministry,

their numbers were very considerable, and their influence greater still.

They knew themselves to be the salt of the earth, and we remember that even

thirty-five years ago the Cameronians of the remoter parts of Galloway held

themselves a little apart in a stiff kind of spiritual independence and even

pride, to which the other denominations looked up, not without a certain awe

and respect.

But the effect on the

Cameronian boy was not always so happy. We were in danger of becoming little

prigs. Whenever we met a boy belonging to the Established Kirk (who learned

paraphrases), we threw a stone at him to bring him to a sense of his

position. If, as Homer says, he was a lassie, we put out our tongue at her.

Religion among the People.

But it is a more

interesting thing to inquire concerning the state of religion among the

people than into the efficiency of the clergy. In many of the best families,

and these too often the poorest, religion was instilled in a very high,

noble, and practical way indeed. Such a house as that of William Burness,

described in the "Cotter's Saturday Night," was a type of many Galloway

homes of last century.

Prayers night and mom were

a certainty, however early the field work might be begun, and however late

the workers were in getting home. On the Sabbath mom especially the sound of

praise went up from every cothouse. In the farm kitchens the whole family

and dependants were gathered together to be instructed in religion.

The "Caratches" were

repeated round the circle, and grandmother in the comer and lisping babe

each took their tum, nor thought it any hardship.

The minister expressed

national characteristics excellently well. But even he of the Cameronian

Kirk was to some extent affected by the tone of learning in the university

towns where he had attended the college, and "gotten lear" and

"understanding of the original tongues." But in the sterling qualities of

many an old Galloway farmer (who, perhaps, never had fifty pounds clear in a

year in his life, and whose whole existence was one of bitter struggle with

the hardest conditions) we get some understanding of how the religion of our

country, so stem and tender, so tempest-tossed and so victorious, stood the

strains of persecution and the frosts of the succeeding century of unbelief.

In the darkest times of indifference there were, at least in Scotland, many

more than seven thousand who never bowed the knee to Baal, and whose mouths

had never kissed him–though, so far as Galloway is concerned, let it not be

forgotten that even this comes with a qualification, like all things merely

human. For it is of the nature of Galloway to share with Providence the

credit of any victory, but to charge it wholly with all disasters. "Wasna

that cleverly dune?" we say when we succeed. "We maun juist submit!" we say

when we fail. A most comfortable theology, which is ever the one for the

most of Galloway folk, whom "chiefly dourness and not fanaticism took to the

hills when Lag came riding with his mandates and letters judicatory."

II.–WHAT WE SEE IN RAIDER

LAND

The hills of Galloway lie

across the crystal Cree as one rides northward towards Glen Trool, much as

the Lebanon lies above the sweltering plains north of Galilee; a land of

promise, cool grey in the shadows, palest olive and blue in the lights. By

chance it is a day of sweltering heat, and as we go up the great glen of

Trool the midday sunshine is almost more than Syrian.

The firs' shadows in the

woods fringing the loch about Eschonquhan are deliciously cool as the swift

cycle drives among them. We get but fleeting glimpses of the water till we

come out on the rocky cliff shelf, which we follow all

Loch Trool.

the way to the farmhouse of

Buchan. Trool lies much like a Perthshire loch, set between the granite and

the bluestone–the whin being upon the southern and the granite upon the

northern side. The firs, which clothe the slopes and cluster thick about the

shores, give it a beautiful and even cultivated appearance. It has a look

more akin to the dwellings of men, and that aggregation of individuals which

we call the world. Yet what is gained in beauty is more than lost in the

characteristic note of untouched solitude which is the rarest pleasure of

him who recognises that God made Galloway.

Trool is somehow of a

newer creation, and the regularity of its pines tells us that it owes much

to the hand of man. Loch Enoch, on the other hand. is plainly and wholly of

God, sculptured by His tempests, its rocks planed down to the quick by the

ancientest glaciers of "The Galloway Cauldron."

The road gradients along

Trool-side are steep as the roof of a house. From more than one point on the

road the loch lies beneath us so close that it seems as if we could toss a

biscuit upon its placid breast. The deep narrow glen may be flooded with

intense and almost Italian sunshine. But the water lies cool, solid, and

intensely indigo at the bottom. Far up the defile we can see Glenhead, lying

snug among its trees, with the sleeping giants of the central hills set

thick about it. Nor it is not long till, passing rushing burns and heathery

slopes on our way, we reach it.

Heartsome content within,

placid stillness without as we ride up–a broad straw hat lying in a friendly

way upon the path–the clamour of children's voices somewhere down by the

meadow–a couple of dogs that welcome us with a chorus of belated

barking-this is Glenhead, a pleasant place for the wandering vagabond to set

his foot upon and rest awhile. Then after a time, out of the coolness of the

narrow latticed sitting-room (where there is such a collection of good books

as makes us think of the nights of winter when the storms rage about the

hill-cinctured farm), we step, lightly following, with many expectations,

the slow, calm, steady shepherd's stride of our friend-the master of all

these fastnesses-as he paces upwards to guide us over his beloved hills.

The Hill Fastnesses.

It is warm work as we

climb. The sun is yet in his strength, and he does not spare us. Like

Falstaff, a fatter but not a better-tempered man, we lard the Iean earth as

we walk along. But the worst is already overpast when we have breasted the

long incline, and find beneath us the still blue circles of the twin lochs

of Glenhead. Before we reach the first crest, we pass beneath a great

granite boulder, concerning which we are told a remarkable story. One day in

autumn, some years ago, a herd boy came running into the farmhouse crying

that the day of judgment had come–or words to that effect. He bad heard a

great rush of rocks down from the overhanging brow of the crag-embattled

precipice above. One great grey stone, huge as a cothouse, had been started

by the heavy rains, and was coming downwards, bringing others along with it,

with a noise like a live avalanche. The master saw it come, and doubtless a

thought for the security of his little homestead crossed his mind. At the

least he expected the rock to crash downward to the great dyke which

protects his cornfields in the hollow. But the mass sank three or four feet

in the soft turf of a "brow," and there to this day it remains embedded. A

manifest providence! And the folk still acknowledge Providence among these

hills–so behindhand are they!

As we mount, we leave away

to the south the green, sheep-studded, sun-flecked side of Curleywee. The

name is surely one which is given to its whaup-haunted solitudes, because of

that most characteristic of moorland sounds-the wailing pipe of the curlew.

"Curleywee-Curleywee-Curleywee." That is exactly what the whaups say in

their airy moorland diminuendo, as with a curve like their own Roman noses

they sink downward into the bogs.

Waterfalls are gleaming in

the clefts–"jaws of water," as the hill folks call them-the distant sound

coming to us pleasant and cool, for we begin to desire great water-draughts,

climbing upwards in the fervent heat. But our guide knows every spring of

water on the hillside, as well as every rock that has sheltered fox or

eagle. There, on the face of that cliff, is the apparently very accessible

eyrie where nested the last of the Eagles of the southern uplands. Year

after year they built up there, protected by the enlightened tenants of

Glenhead, who did not grudge a stray dead lamb, in order that the noble bird

might dwell in his ancient fastnesses and possess his soul–for surely so

noble a bird has a soul–in peace. As a reward for his hospitality, our guide

keeps a better understanding of that great lsaian text, "They shall mount up

with wings as eagles," than he could obtain from any sermon or commentary in

the round world. For has he not seen the great bird strike a grouse on the

wing, recover itself from the blow, then, stooping earthwards, catch the

dead bird before it had time to fall to the ground? Also he has seen the

pair floating far up in the blue, twin specks against the supreme azure.

Generally only one of the young was reared to eaglehood, though sometimes

there might be two. But on every occasion the old ones beat off their

offspring as soon as these could fly, and compelled their children to seek

pastures new. Some years ago, however–in the later seventies–the eagles left

Glenhead and removed to a more inaccessible rock crevice upon the rocky side

of the Back Hill 0' Buchan. But not for long. Disturbed in his ancient seat,

though his friends had done all in their power to protect him, he finally

withdrew himself. His mate was shot by some ignorant scoundrel prowling with

a gun, somewhere over in the neighbourhood of Loch Doon. We have no doubt

that the carcass is the proud possession of some local collector, to whom,

as well as to the original "gunning idiot," we would gladly present, at our

own expense, tight-fitting suits of tar and feather.

Behind us, as we rise

upwards into the realms of blue, are the heights of Lamachan and Bennanbrack.

Past the side of Curleywee it is possible to look into the great chasm of

air in which, unseen and far beneath us, lies Loch Dee.

We gain the top of the

high boulder-strewn ridge. Fantastic shapes, carved out of the gleaming grey

granite, are all about. Those on the ridges against the sky look for all the

world like polar-bears with their long Jean noses thrust

forward to scent the seals

on the floes or the salmon running up the Arctic 'rapids to spawn. To our

right, above Loch Valley, is a boulder which is so poised that it

constitutes a " logan" or rocking-stone. It is so delicately set as to be

moved by the blowing of the wind.

The Land of the Lochs.

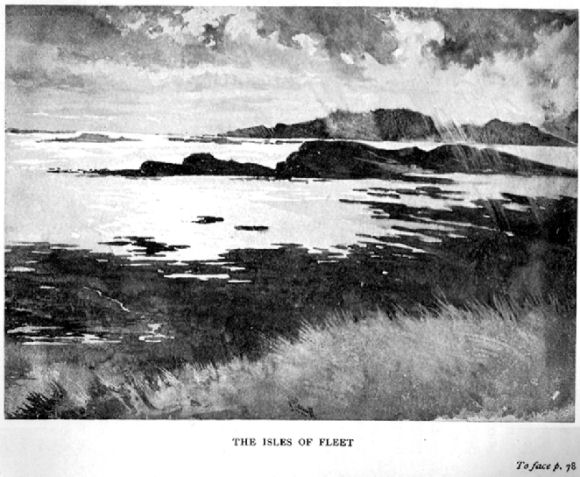

Loch Valley and Loch

Neldricken form, with the twin lochs of Glenhead, a water system of their

own, connected with Glen Trool by the rapid torrential burn called the

Gairlin, that flashes downward through the narrow ravine which we leave

behind us to our left as we go upward. At the beginning of the bum, where it

escapes from Loch Valley, are to be seen the remains of a weir which was

erected in order to raise artificially the level of the loch, submerging in

the process most of the shining beaches of silver granite sand. But the loch

was too strong for the puny works of man. One fine day, warm and sunny, our

guide tells us that he was working with his sheep high up on the hill, when

the roar and rattle of great stones carried along by the water brought him

down the "screes" at a run. Loch Valley had broken loose. The weir was no

more, and the Gairlin bum was coming down in a ten-foot breast, creamy foam

cresting it like an ocean wave. Down the glen it went like a miniature

Johnstown disaster, while the boulders crashed and ground together with the

rush of the water. When Loch Valley was again seen, it had resumed its

pristine aspect–that which it had worn since the viscous granite paste

finished oozing out in sheets from the great cracks in the Silurian rocks,

and the glaciers had done their work of grinding down its spurs and

outliers. It takes a Napoleon of engineering to fool with Loch Valley.

From this point we keep to

the right, passing the huge moraine which guards the end of the loch and

effectually prevents a still greater flood than that which our master

shepherd witnessed. These mounds are full of what are called in the

neighbourhood "jingling stones." Without doubt they consist of sand and

shingle, so riddled with great boulders that the crevices within are

constantly being filled up and forming anew as the sand shifts and sifts

among the stones. As we proceed the sun is shining over the shoulder of the

Merrick, and we are bound to hasten, for there is yet far to go. Neldricken

and Valley are wide-spreading mountain lakes, lying deep among the hills

which spread nearly twenty miles in every direction. The sides of the glens

are seared with the downward rush of many waters. Waterspouts are common on

these great hills. It is no uncommon thing for the level of a moorland burn

to be raised six or ten feet in the course of a few minutes. A "Skyreburn"

warning is proverbial in the south country along Solwayside. But the Mid

Burn, and those which strike north from Loch Enoch tableland, hardly even

give a man time to step across their normal noisy brattle till they are

roaring red and it is twenty or thirty feet from bank to bank.

These big boulders, heaped

up on one another, often make most evil traps for sheep to fall into.

Sometimes it needs crowbars and the strength of men to extricate those that

happen to be caught there. The dogs that range the hills, questing after

white hares and red foxes, are quick to scent out these poor prisoners.

These prison-houses are named "yirds " by the shepherds. They are especially

numerous on the Hill of Glenhead, at a place called Jartness, which

overlooks Loch Valley. And indeed it is difficult anywhere to see a more

leg-breaking place. It will compare even with that paragon of desolation,

the Back Hill 0' Buchan. It is understood in the district that when the

Great Architect looked upon His handicraft and found it very good, He made a

mental reservation in the case of the "Back Hill o' Buchan."

Utmost Enoch.

But our eyes are upwards.

Loch Enoch is the goal of our desire. For nights past we have dreamed of its

lonely fastnesses. Now they are immediately before us. Enoch is literally a

lake in cloudland. Over-head frowns what might be the mural fortification of

some titanic Mount Valerien or Ehrenbreitstein. The solemn battlemented

lines rise above us so high that they are only dominated by the great mass

of the Merrick. It is hard to believe that a cliff so abrupt and stately has

a lake on its summit. Yet it is so. The fortress-like breastwork falls away

in a huge embrasure on either side, and it is into the trough which lies

nearest the Merrick that we direct our steps. As we go we fall talking of

strange sights seen on the hills. Our guide, striding before, stalwart and

strong, flings pearls of information over his shoulder as he goes, and to

the steady stream of talk the foot moves lighter over the heather. Beneath

us we have now a strange sight–in a manner the most wonderful thing we have

yet seen. On the edge of Loch Neldricken lies a mass of green and matted

reeds–brilliantly emerald, with the deceitful brilliancy of a "qua kin'

qua," or shaking bog, of bottomless black mud. In the centre of this green

bed is a perfectly-delined circle of intensely black water, as exact as

though cut with a compass. It is the Murder Hole, of gloomy memory. Here,

says the man of the hill, is a very strong spring which does not freeze in

the hardest winters, yet is avoided by man and beast. It is certain that if

this gloomy Avernus were given the gift of narration it would tell of lost

men on the hills, forwandered and drowned in its dark depths.

The Merrick begins to

tower above us with its solemn head as we thread our way upward towards the

plateau on which Loch Enoch lies. We are so high now that we can see

backward over the whole region of Trool and the Loch Valley basin. Behind

us, on the extreme south, connected with the ridge of the Merrick, is Buchan

Hill, the farmhouse of which lies low down by the side of Loch Trool. Across

a wilderness of tangled ridge-boulder and morass is the Long Hill of the

Dungeon, depressed to the south into the" Wolf’s Slock"–or throat. Now our

Loch Enoch fortress is almost stormed. Step by step we have been rising

above the rugged desolations of the spurs of the Merrick.

"Bide a wee," says our

guide, "and I will show you a new world." He strides on, a very sturdy

Columbus. The new world comes upon us, and one of great marvel it is. At

first the haze somewhat hides it–so high are we that we seem to be on the

roof of the Southern Creation–riding on the rigging of all things, as indeed

we are. Half-a-dozen steps and "There's Loch Enoch!" says Columbus, with a

pretty taste in climax.

Strangest sight in all this Galloway of strange sights is Loch Enoch–so

truly another world that we cannot wonder if the trouts of this uncanny

water high among the hills decline to wear tails in the ordinary fashion of

common and undistinguished trouts in lowland lakes, but carry them docked

and rounded after a mode of their own.

This

still evening Enoch glows like a glittering silver-rimmed pearl looking out

of the tangled grey and purple of its surrounding with the strength,

tenderness, and meaning of a human eye. The Merrick soars away above in two

great precipices, whereon Thomas Grierson, writing in 1846, tells us that he

found marks showing that the Ordnance surveyors had occupied their hours of

leisure in hurling great boulders down into the loch. There were fewer sheep

on the Merrick side in those days, or else the tenant of that farm might

with reason have objected. It seems, however, something of a jest to suppose

that this heathery desolation is really a farm, for the possession of which

actual money is paid. Yet our guide tells of an old shepherd, many a year

the herd of the Merrick, who, when removed by his master to the care of an

easier and lower hill, grew positively homesick for the stem majesty of the

monarch of South Country mountains, and related tales of the Brocken

spectres he had often seen when the sun was at his back and the great chasm

of Enoch lay beneath him swimming with mist.

Loch-in-Loch.

Loch Enoch spreads out beneath us in an intricate tangle of bays and

promontories. As we sit above the loch, the large island with the small loch

within it is very prominent. The " Loch-in-Loch" is of a deeper and more

distinct blue than the general surface of Loch Enoch, perhaps owing to its

green and white setting upon the grassy boulder-strewn island. Another

island to the east also breaks the surface of the loch, and the bold jutting

granite piers, deeply embayed, the gleaming silver sands, the far-reaching

capes so bewilder the eye that it becomes difficult to distinguish island

from mainland. It increases our pleasure when the guide says of the stray

sheep, which look over the boulders with a shy and startled expression:

"These sheep do not often get sight of a man." Probably no part of the

Highlands is so free from the presence of mankind as these Southern uplands

of Galloway, which were the very fastness and fortress of the Westland Whigs

in the fierce days of the Killing.

On the

east side of Loch Enoch the Dungeon Hill rises grandly, a thunder-splintered

ridge of boulders and pinnacles, on whose slopes we see strewn the very

bones of creation. Nature has got down here to her pristine elements, and so

old is the country, that we seem to see the whole turmoil of "taps and

tourocks "–very much as they were when the last of the Galloway glaciers

melted slowly away and left the long ice-vexed land at rest under the blow

of the winds and the open heaven.

Right

in front of us the Star Hill, called also Mulwharchar, lifts itself up into

the clear depths of the evening sky–a great cone rounded like a hayrick. At

its foot we can see the two exits of Loch Enoch–the true and the false. Our

guide points out to us that the Ordnance Survey map makes a mistake with

regard to the outlet of Loch Enoch, showing an exit by the Pulscraig Burn at

the north-east corner towards Loch Doon–when as a matter of fact there is

not a drop of water issuing in that direction, all the water passing by the

northwest comer towards Loch Macaterick.

Beyond

the levels of desolate, granite-bound, silver-sanded Loch Enoch lies a

tumbled wiIderness of hills. To the left of the Star is the plateau of the

Rig of Millmore, a wide and weary waste, gleaming everywhere with grey tarns

and shining "Lochans." Beyond these again are the Kirreoch hills, and the

pale blue ridges of Shalloch-on-Minnoch. Every name is interesting here,

every local appellation has some reason annexed to it, so that the study of

the Ordnance map–even though the official nomenclature enshrines many

mistakes is weighted with much suggestion. But no name or description can

give an idea of Loch Enoch itself, lifted up (as it were) close against the

sky–nearly 1700 feet above the sea–with the giant Merrick on one side, the

weird Dungeon on the other, and beyond only the grey wilderness stretching

mysteriously out into the twilight of the north.

It is

with feelings of regret that we take leave of Loch Enoch, and, skirting its

edge, make our way eastward to the Dungeon Hill, in order that we may peer

down for a moment into the misty depths of the Dungeon of Buchan. A scramble

among the screes, a climb among the boulders, and we are on the edge of the

Wolf's Slock–the appropriately named wide throat up which so many marauding

expeditions have come and gone. We crouch behind a rock and look downward,

glad for a moment to get into shelter. For even in the clear warm August

night the wind has a shrewd edge to it at these altitudes. Buchan's Dungeon

swims beneath us, blue with misty vapour. We can see two of the three lochs

of the Dungeon. It seems as if we could almost dive into the abyss, and swim

gently downwards to that level plain, across which the Cooran Lane, the

Sauch Burn, and the Shiel Burn are winding through "fozy" mosses and

dangerous sands. It is not for any man to venture lightly at nightfall, or

even in broad daylight, among the links of the Cooran, as it saunters its

way through the silver flow of Buchan. The old royal fastness keeps its

secret well.

Far

across in the distance we can see the lonely steading of the Black Hill 0'

the Bush, and still farther off the great green whalebacks of Corscrine and

others of the featureless Kells range, deepening into grey purple with a

bloom upon them where the heather grows thickest, like the skin on a dusky

peach.

The

Dusk on Enoch.

Now at last the sun is dipping beyond the Merrick, and all the valley

to the south, or rather the maze of valleys, grow dim in the shadow. Loch

Enoch has turned from gleaming pearl to dusky lead, or, more accurately

still, to the dull shimmer that one may see on so unpoetical a thing as

cooling gravy. So great are the straits of comparison to which the

conscientious artist in words is driven in the description of scenery. But

we must turn home-ward. The Merrick itself is dusking. Enoch falls behind

its hummocks of ice worn rocks. We descend rapidly into the valley which

leads to Loch Neldricken, threading our way till we come to the grave of the

wanderer Cameron, who lost his road and perished in a storm alone upon the

waste. The form of the body is still plainly to be seen upon the emerald

turf, and certainly the boulders around give good evidence of the power of

the winter storms. Our guide, with his strong hill voice, tells us of these

times of fear, when winter sends the spindrift of the snow hurtling across

the mountains. The storms here are rarely fatal to many sheep, partly

because it is the office of the shepherd to keep an eye upon the places

where the sheep are collected, but still more because of a very wonderful

piece of special adaptation. It is not upon these rough hills of boulder and

heather that many sheep are lost. Smoother hills are far more dangerous. The

overlapping rocks, tossed and set in fantastic congeries of crags, seem to

suck in the snow automatically. The granite blocks, lying all around, give

shelter, and as it were provide a thousand dustbins, into which the wind,

careful and untiring housemaid, sweeps the snow almost as it falls. At

least, since the "close cover" of the famous "sixteen drifty days," there

has been recorded here no great or widespread loss of the black-faced

sheep–the current coin of the hills.

Presently we are skirting the "silver sand" of Loch Neldricken, which, as

our guide says, would be good scythe sharpening, were it not that so much

better can be got at Loch Enoch. For from these uplands the "straikes" of

the lowland scythes are supplied with the pure flinty granite sand which

puts an edge upon the blades that cut the hay and win the golden corn. Emery

straikes are used for easy corn by some newfangled people who are ill to

satisfy with the good gifts by Nature provided. But the stalwart men who mow

in the water meadows know well that nothing can put the strident gripping

edge upon their blade like the true Loch Enoch granite sand.

It is

dusking into dark as we master the final slope, and to the barking of dogs,

and the cheerful voices of kindly folk. we overpass the last hill dyke, and

enter the sheltering homestead of Glenhead, which looks so charmingly out

over its little crofts down to the precipice-circled depths of Loch Trool.

The

Buchts of the Mid Burn.

Ere we came

over the hill, however, we entered the sheep "buchts," a very fortress of

immense granite blocks, set upon a still more adamantine foundation of solid

rock–a monument of stem and determined workmanship. Indeed, something more

than sheep bars are needed to restrain the breed of sheep that is to be

found hereabouts–animals that by no means conduct themselves like slow-going

and respectable Southdowns or aldermanic Cheviots, but fight like Turks,

climb like goats, and run like hares, We remember taking a newly-imported

Englishman over a Galloway hill. We were climbing in the heat, when

suddenly, with a rush, a fearsome animal, with twisted horns half a yard

long, and a black and threatening face, rose behind us, leapt a wide

watercourse and disappeared up the precipice, amid a rattle of stones

scattering downward from its hoofs.

"What wild beast is that?"

asked our companion in some trepidation.

"A Galloway tip," we

replied.

"And what might a 'tip'

be, when he's at home?" "Only a sheep," we replied calmly.

The Englishman, accustomed

to the breed of Leicester, looked at us with a curious expression in his

eyes.

"If I were you I would not

try to take in an orphan-and one far from home," he said. "We English may be

verdant, but at least we do know a sheep when we see one."

And to this day he does

not believe it was "only a sheep" that he saw on our slopes of granite and

heather.

As we lay asleep that

night, the sound of the wind drawing lightly up and down the valleys

breathed in upon us, and the subtle smell of honey came to us in the early

morning from the ranged beehives under the wall. Around was a great and

sweet peace–pure air refined by heather and the wild winds–content so

perfect that we wished to live for ever with the chief guide and his partner

divided between the travail of writing and the rest of reading.

But it is morning over

Glen Trool. The light has poured over from the east, flooding the valley.

But there is a mist coming and going upon Curleywee. Lamachan hides his

head. Only the "taps" towards Loch Dee are clear.

We are out amid the stir

of the farmyard with its pleasant familiar noises.

"D'ye see yon three stanes

on the hill atween it and the sky? " asks the Man of the Hills.

"We see them," we reply,

making out three knobs upon the ultimate ridges.

"Weel, yon's your road for

Loch Dee, but you'll hae to gang a guid bit back."

He is right–the canny

Galwegian–Loch Dee is over there, but it certainly is a "guid bit back."

Clashdaan.

It was easier to get the

direction of the three silent watchers on the hill crest than to keep

straight for them over the tangle of heather and moss which lies between.

The way to the loch seems to be over the white granite bed of a burn that

comes down from the rugged sides of Craiglee. Following it we reach the high

and precipitous side of the hill, and follow the bum up to the "lirk of the

hill" where the streamlet takes its rise. This burn, which comes over the

white rocks in sheets in wet weather, is named the Trostan. Near the summit

of Craiglee lies a little loch, high up among the crags–called the Dhu Loch;

sombre, dark, and impressive. From the jutting point of rock, called the

Snibe, which looks towards the north, we see the great chasm of the Dungeon

from the south. We can catch the glint of the Dungeon Lochs far to the

north–all three of them–while nearer the Cooran Lane and other burns seek

their ways through treacherous sands and "wauchie wallees" to Loch Dee,

which lies beneath us to the south. Seen from the Snibe, Loch Dee looks its

best. It has indeed no such remarkable or distinctive character as the

splendid series of lochs between Glenhead and Enoch. It would be but a wild

sheet of water 0n a featureless moor, were it not that it derives dignity

from the imminent sides of Craiglee and the Dungeon.

We reach the bottom by a

narrow cleft that leads downwards from the Snibe towards the loeb. It is

called the Clint of Clashdaan. Then comes a wading wet foot through some

boggy land grazed over by sheep (which must surely be born web-footed), till

we reach the boathouse on the western shore of Loch Dee. Beyond is a strip

of sand so inviting and delightful to the feet that in a few moments we are

swimming across the narrows of the loch. Then follows a run on the beach in

costume which might occasion some remark on Brighton beach, and a brisk rub

down with the outside of a rough coat of Harris tweed in lieu of a towel. In

a few minutes the steep sides of Curleywee are bringing out a brisk reaction

of perspiration. It had been our thought that from Curleywee it might be

possible to obtain a general view of the country of the Granite Lochs, but

the persistent downward sweep of the mist makes this impossible. Yet by

persevering along the verge we bave some very striking glimpses down into

the deep glen of Trool, at the upper end of which lie cosily enough the

farmhouses of Buchan and Glenhead. High up on the side of Curleywee, where

the whaup are crying the name of the mountain, like porters at a railway

station, we come upon two or three deep little pools in which the trouts are

rising. How they get up there is a question which others must settle. There

they are, and there for us they shall stop. If they got up the "jaws" which

come pouring over the side of the hill somewhat farther down, they are

certainly genuine acrobat–he descendants of some prehistoric freshwater

flying-fishes.

As soon as we leave the

ridge above, it is downhill steeply all the way till we come to hospitable

Glenhead, where by the burn the warm-hearted master is working quietly among

the sheaves. It does one good in the turmoil of the world to think that

there are kind souls living so quietly and happily thus remote from the

world, with the Merrick and the Dungeon lifting their heads up into the

clouds above them, and over all Loch Enoch looking up to God, with a face

sternly sweet, only less lonely than Himself.

III.-WHAT WE SAY THERE, AND

HOW WE SAY IT

Galloway Humour.

No one can pass even a

short space of time among the people of our Galloway countryside without

being made aware, in ways pleasant and the reverse, of the great amount of

popular humour ever bubbling up from the heart of the common people. It is

to them the salt of intercourse, the grease on the dragging axles of their

life. Not often does it reach the stage of being expressed in literary form.

It is lost in the stir of farm-byres, in the cheerful talk of ingle-nooks.

You can hear it being windily exchanged in the greetings of shepherds crying

the one to the other across the valleys. It finds way in the observations of

passing ploughmen as they meet on the way to the mill, and kirk, and market.

For example, an artist is

busy at his easel by the wayside.1 A rustic is looking over his

shoulder in the manner of the free and independent Scot. A brother rustic is

in a field near by with his hands in his pockets. He is not sure whether it

is worth while to take the trouble to mount the dyke, for the uncertain

pleasure of looking at a mere picture. "What is he doing, Jock? "asks he in

the field of his better-situated mate. "Drawin' wi' pent!" returns Jock,

over his shoulder. "Is't bonny?" again asks the son of toil in the field. "

OCHT BUT BONNY!" comes back the prompt and decided answer of the critic. Of

consideration for the artist's feelings there is not a trace. Yet both of

these rustics will appreciatively relate the incident on coming in from the

field and washing

It was that

admirable Galloway artist and good friend Mr. W. S. M'George, A.R.S.A.

themselves, concluding with this rider: "An' he didna look

ower weeI pleased, I can tell ye! Did he, Jock?"

This great body of popular humour first found its way into

the channels of our historic literature mainly in the form of ballads and

songs–often very free in taste and broad in expression, because they were

struck from the rustic heart, and accordingly smelt of the farmyard, where

common things are called by their common names.

But in time these rose higher in the poems of Lindsay, in

some of Knox's prose–very grim and humorsome it is–and in Dunbar and

Henrysoun, mixed in each case with strong personal elements. Burns alone

caught and held the full force of it, for he was of the soil, and grew up

near to it. So that to all time he must remain the finest expression of

almost all forms of lowland feeling. As to prose, chap-books and pamphlets

innumerable carried on the stream, which for the most part was conveyed

underground, till, in the fulness of time, Walter Scott came to give

Scottish humour world-wide fame in the noble series of imaginative writings

by which he set his native land beside the England of William Shakespeare.

Scott a Literary Harvester.

Scott was the first great harvester of our old

national stock of humour, and right widely he gathered, as those know who

have striven to follow in his trail. Hardly

a chap-book but he has been through, hardly a

generation of our nationaI history that he has not touched and adorned. Yet,

because Scotland is a wide place, and Scottish humour also in every sense

broad, no future humorist need feel straitened within their ample bounds.

Of all the cherished delusions of the

inhabitant of the southern part of Great Britain with regard to his northern

brother, the most astonishing is the belief that the Scot is destitute of

humour. Other delusions may be dissipated by a tourist ticket and the ascent

of Ben Nevis–such as that, north of the Tweed, we dress solely in the

kilt–which we do not, at least, during the day; that we support life solely

upon haggis and the product of the national distilleries; that

the professors of Edinburgh

University, being "pauged fu' 0' lear," communicate the same to their

students in the Gaelic–a thing which, though not altogether unprecedented,

is, I am told, considered somewhat informal by the Senatus.

These may be taken as

examples of the grosser delusions which leap to the eye, and are received

upon the ear as often as the subject of Scotland arises in a company of the

untravelled, and, as we should say, "glaikit Englisher."

I should much like to say,

here and now, as Professor Blackie used to remark vigorously, that "every

person who despises Scottish national humour proves himself to be either a

conceited puppy or an ignorant fool." Personally I should like to add–"or

both! "

R.L. Stevenson on the Grey

Land.

There is a classical

passage in the works of Mr. R. L. Stevenson, which, with the metrical

psalms, the poems of Bums, and the Catechism, ought to be required of every

Scottish man or woman before they be on the allowed to think of getting

married. It is sad to see young people setting up house and so ilI-fitted

for the battle of life. The passage from Mr. Stevenson is as follows. I

protest that I never can read it, even for the hundredth time, without a

certain sympathetic moisture of the eye, for it might have been written of

Galloway, and even of Balmaghie :–

"There is no special

loveliness in that grey country, with its rainy, sea-beat archipelago; its

fields of dark mountains; its unsightly places, black with coal; its

treeless, sour, unfriendly-looking corn-lands; its quaint, grey, castled

city, where the bells clash of a Sunday, and the wind squalls, and the salt

showers fly and beat. I do not know if I desire to live there; but let me

hear, in some far land, a kindred voice sing out, 'Oh! why left I my hame?'

and it seems at once as if no beauty under the kind heavens, and no society

of the good and wise, can repay me for my absence from my country. And

though I would rather die elsewhere, yet in my heart of hearts I long to be

buried among good Scots clods. I will say it fairly, it grows upon me with

every year; there are no stars so lovely as Edinburgh street-lamps. The

happiest lot on earth is to be born a Scotsman. You must pay for it in many

ways, as for all other advantages on earth. You have to learn the

Paraphrases and the Shorter Catechism; you generally take to drink; your

youth, so far as I can make out, is a time of louder war against society, of

more outcry, and tears, and turmoil, than if you were born, for instance, in

England. But, somehow, life is warmer and closer, the hearth burns more

redly; the lights of home shine softer on the rainy street, the very names,

endeared in verse and music, cling nearer round our hearts. An Englishman

may meet an Englishman to-morrow, upon Chimborazo, and neither of them care;

but when the Scotch wine-grower told me of Mons Meg, it was like magic.

"From the dim shieling on

the misty island,

Mountains divide us and a

world of seas ;

Yet still our hearts are

true, our hearts are Highland,

And we in dreams behold the

Hebrides. '"

Our humour lies so near

our feeling for our country that I would almost say, if we do not feel this

quotation–aye, and feel it in our bones–we may take it for granted that both

the humour and the pathos of Scotland are to be hid from us during the term

of our natural lives.

However, as Mr. Whistler

said when a friend pointed out to him a certain suggestion of the landscape

Whistlerian in an actual sunset–" Ah, yes, nature is creeping up!" So we may

say, with reference to its appreciation of Scottish humour, England is

certainly "creeping up." The numbers of editions of Scott, edited,

illustrated, and annotated, plain and coloured, prove it. It is always a

good brick to throw at a literary pessimist, to tell him the number of

editions of Scott that have appeared during the last half-dozen years. I do

not know how many there are–I have no idea–but I always say fifty-three and

four more coming, for that sounds exact, and as if one had all the

statistics up one's sleeve. If you say these little things with a confident

air, you are never contradicted. No one knows any different. It is a habit

worth acquiring. I am not proud of the accomplishment, but I don't mind

saying that I learned the trick from listening to the evidence of skilled

witnesses in His Majesty's Courts of Law.

Our Scottish Loyalty.

Let us "look for a moment

at our national humour of fact. We Galwegians were, for instance, a people

intensely loyal to our kings and queens. Yet, so long as they were with us,

we dissembled our affection. Alas, we never told our love! In fact, we

generally rebelled against them, so that they might have a good time hanging

us up in the Grassmarket and ornamenting the Netherbow with our heads. But

as soon as we had driven these same kings and queens into exile, we became

tremendously loyal, and kept up constant trokings with the exiled at

Carisbrook, in Holland, or drinking to "the king over the water." Our very

Galloway Cameronians became Jacobites and split on the subject, as our

Scottish kirks always did–being apparently of the variety of animalculae:

which multiply by fission. So we went on, till we got them back, and again

seated on the throne with a firm seat and a tight rein. Then we rebelled

once more, just to keep them aware of themselves. Thus our national humour

expressed itself in our history.

Our Southland Feuds.

Or again we had our family

feuds. It mattered not whether we were kilted Macs of the North, or

steel-capped, leathern jacked Kennedies and Douglasses of the South, we

loved our name and clan, and stood for them even against king and country.

But, nevertheless, we arose early in the morning and bad family worship,

like the respected and respectable Mr. John Mure of Auchendraine. Then we

rode forth, with spear and pistolet, to convince some erring brother of the

clan that he must not do so. I came upon a delightful entry from an old

family register the other day. It was much mixed up with religious

reflection, but it had this trifling memorandum interpolated to break the

placid flow of the spiritual meditation: "This day and date oor Jock stickit

to deid Wat Maxwell in Traquair! Glory be to the Father and to the Son! "

This also is a part of our

national humour of history.

A certain Master Adam

Blackadder was an apprentice boy in Stirling in the troublous times of the

Covenant. The military were coming, and the whole Whiggish town took flight.

"' 'I would have been for

running too,' says young Adam, being a merchant's loon. 'I would have been

for the running too, but my master discharged me from leaving the shop.

For,' said he, 'they will not have the confidence to take the like of you, a

silly young lad.' However, a few days thereafter I was gripped by two

messengers early in the morning, who, for haste, would not suffer me to tie

up my stockings, or put about my cravat, but hurried me away to Provost

Russel's lodgings–a violent persecutor and ignorant wretch! The first word

he spak to me (putting on his breeches) was, 'Is not this braw wark, sirr,

that we maun be troubled wi' the like 0' you?' I answered (brave loon,

Adam!), 'Ye hae gotten a braw prize, my lord, that has ciaucht a poor

'prentice I' He answered, 'We canna help it, sir; we must obey the king's

lawes !' 'King's lawes, my lord,' I says, 'there is no such lawes under the

sun I' For I had heard that, by the bond, heritors were bound for their

tenants and masters for their servants–and not servants for themselves (and

here Adam had him!). 'No such lawes, sirr I' says our sweet Provost; 'ye

lee'ed like a knave and traitour, as ye are. So, sirr, ye come not here to

dispute the matter. Away with him, away with him to the prison.'''

So accordingly they haled

away the too humorous apprentice of Stirling to Bridewell, where, as he

says, and as we should expect, he was never merrier in his life–albeit with

iron gates about him, and waiting on the mercy of the "sweet provost," whom

he surprised "putting on his breeks."

But how exquisitely

Scottish and humorous is the whole scene–the lad, not to be "feared," and

well content to get the better of the Provost in the battle of words,

derives an admirable satisfaction from the difficulties of his enemy, who

has perforce to argue while" putting on his breeks," a time when teguments,

not arguments, are most fitting. Meanwhile the Provost is grimly conscious

that he is getting the worst of it, and that what the 'prentice loon said to

him will be a sad jest when the bailies congregate round the civic

punchbowl. Yet, for all that, he is not unappreciative of the lad's national

right to say his say, and, not without some reluctance, silences him with

the incontrovertible argument of the "iron gates:" This also is Scottish and

national, and could hardly be native elsewhere.

The Humour of History.

As we go on to consider

these and other similar circumstances chronicled in our lowland history,

certain ill-defined but obvious sorts and kinds of national humour emerge.

They look at us out of all manner of unexpected places–out of the records of

the great Seal, out of the minutes of the Privy Council, out of the State

trials, out of the findings of Galloway juries. " We find that the prisoner

killit not the particular man aforesaid, yet that neverthelesse he is

deserving of hanging." On general grounds, it is to be presumed, and to

encourage the others! So hanged the acquitted man duly was, much as Mossman

was hanged, on May 20, 1785, because he " cam' frae Carrick!"

Disentangling some of

these threads of humour which shoot scarlet through the hodden grey of our

Southland records, we can distinguish four kinds of historical humour–first,

the humour which I propose, without any particular law or licence, to call

by analogy" Polter Humour." The best attested of all spectral apparitions is

a certain Galloway ghost–the spirit which troubled the cothouse of Collin,

in the parish of Rerrick, for many months, and was only finally exorcised

after many wrestlings with all the ministers of the country-side in

Presbytery assembled. It was a merry and noisy spirit, of the type called (I

am informed) the Polter Ghost, a perfect master of the whistling, pinching,

vexing, stone-throwing, spiritualistic athletic. Hence, following this

analogy, we may

call a

considerable part of our lowland humour "Polter Humour." It is the same kind

of thing which, mixed with the animal spirits and primitive methods of the

undergraduate, leads him occasionally to thump upon the floor of philosophy

class-rooms in a manner most unphilosophic. I am, it may be, thinking of the

things that were in the good old times, when it was a mistake, trivial in

the extreme, to forget one's college note-book, but an offence capital to

leave behind one's stick. But still the historic Polter Humour of Scotland

is largely the humour of the unlicked cub, playing with such dangerous

weapons as swords and battle-axes, instead of bootlaces and blacking.

The Fiction of the

Historian.

"There is no discourse

between a full man and a fasting. Sit ye doon, Sir Patrick Grey," says the

Black Douglas to the king's messenger, sent to Thrieve Castle to demand the

release of Maclellan of Bombie. Sir Patrick who mIght have known better,

sits him down. The Black Douglas moves his hand and his eyebrow once, and

even while the messenger is solacing himself with "doo-tairt" and a cup of

sack, poor Maclellan is had out to the green and beheaded. Sir Patrick

finishes, and wipes his five-pronged forks in the national manner underneath

his doublet. He is ready to talk business, and so is the Black Douglas–now.

"There is your man. Tell His Majesty he is most welcome to him," says the

Douglas; "it is a pity that he wants the head! " This, though doubtless

wholly invented by the historian, is a good example of the Polter Humour in

excelsis–the undergraduate playing with the headsman's axe instead of

the harmless necessary cudgel.

This is a primitive kind

of humour of savage origin; and how many varieties of it there are among

savage tribes, and amongst that largest of all savage tribes, the noble

outlaw Ishmaels of the world, Boys–Mr. Andrew Lang alone knows.

Of this Polter Humour,

perhaps the finest instances are to be found in the chap-books of the latter

half of the eighteenth century and the first ten years of the nineteenth. So

soon as Scott had made the Scottish dialect into a national

Polter

Humour.

language, the edge seemed completely to go off these productions. With

one consent they became flat, stale, and unprofitable. Indeed, they can

hardly be called strictly "profitable" reading at the best. For it is like

walking down a South Italian lane to read them, so thickly do causes of

offence lie around. But for all that, in them we have the rough

give-and-take of life at the country weddings, the holy (airs, the kirns and

christenings of an older time. I never realised how great and clean Robert

Burns was, till I saw from what a state of utter depravity he has rescued

such homely topics as these. Yet in these days of family magazines we are

uneasily conscious that even Robert Bums has need to have his feet wiped

before he comes into our parlours. As a corrective to this over-refinement,

I should prescribe a counter-irritant in the shape of a short but drastic

course in the dialect chap-books of the final thirty years of the eighteenth

century.

In the

novels of Smollett is to be found the more (or less) literary expression of

this form of humour. True, one cannot read very much of it at a time, for

the effect of a score of pages acts physically on the stomach like

sea-sickness. But yet we cannot deny that there is this Polter element in

Scottish humour, though the fact has been largely and conveniently forgotten

in these days. There are, however, some few pearls distributed among an

inordinate number of swine-sties. Yet we can see the origin, or at least the

manifestation, of this peculiar humour in the old civic enactment which

caused it to be proclaimed that any citizen walking down the Canongate upon

the side-causeways after a certain hour of e'en, did so at "the peril of his

head" There is, also, to this day a type of sturdy, full-blooded Scot, who

cannot imagine anything much funnier than the emptying of a pail of "suds"

out of a window–upon some one else's head. Sometimes this gentleman gets

into the House of Commons, and laughs boisterously when another member sits

down upon his new and glossy hat, which cost him a guinea that morning.

Among

the tales of James Hogg (who, though not of Galloway, deserved to be) there

are many examples of Polter Humour. Hogg is, in some of his many rambling

stories, the greatest example in literature of the Scottish picaresque. He

delights to carry his hero-who is generally nobody in particular, only a

hero–from adventure to adventure without halt or plot, depending upon the

swing of the incident to carry him through. And, indeed, so it mostly does.

"The Bridal of Polmood," for instance, is of this class. It is not a great

original work, like the "Confessions of a Justified Sinner," or a delightful

medley of tales like "The Shepherd's Calendar." But it is a sufficiently

readable story, at least as like the life of the times as Tennyson's courtly

knights are to the actual Round Table men of Arthur the King. In the

"Adventures of Basil Lee" and in "Widow Watts' Courtship," we find more of

the PoIter Humour. But, on the whole, the finest instance of Hogg's rattling

give-and-take is his briskly humorous and admirable story of "The Souters of

Selkirk."

From

recent Scottish literature this rough and thoroughly national species of

humour has been almost banished. But there is no reason why, having cleaned

its feet a little, the Polter Humour might not be revived. There is plenty

of it, healthy and hearty, surviving in the nooks and comers of the hills.

Irony.

The second species of Galloway (and Scottish) humour which I shall try to

discriminate is what, for lack of a better name, I shall call the Humour of

Irony. It is a quieter variety of the last. Of this sort, and to me an

exquisite example, is the advice Donald Cargill offered to Claverhouse as he

was riding from the field of Drumclog, after his defeat, as hard as his

horse could gallop. "Will ye no bide for the afternoon diet of worship?" A

jest which did credit to the grim old "faithful contender," considering that

he had been so lately a prisoner in the hands of John Graham himself. I am

sure that Claverhouse appreciated the ironical edge of the observation, even

if he did not forget the jester. But my Lord Dundee could be ironical

himself with some pith.

"Two

soldiers reported a squabble between two of their officers to Colonel

Graham.

" 'How

knew ye of the matter?' said Claverhouse. '" 'Ve saw it,' they replied.

"I But

how saw ye it?' he continued, pressing them.

"I We

were on guard, and, hearing both din and turmoil, we set down our pieces and

ran to see.'

"Whereupon Colonel Graham did arise, and gave them many sore paiks, because

that they had left their duty to gad about and gaze on that which concerned

them not."

In like

manner, and in the same excellent antique style, it is told of Duke Rothes

that, finding that his lady was going just a step too far in the freedom

with which she entertained proscribed ministers under his very nose, he sent

her ladyship a message, that it behoved her to keep her "black-coated

messans" closer to her heel, or else that he would be obliged to kennel them

for her.

Perhaps

the finest instance of this humour is the well-known story, probably

entirely apocryphal, but none the less worthy on that account, of the

south-country laird, who, with his man John, was riding to market. (The tale

is, I think, in "Dean Ramsay," and, writing far from books, I quote from

memory.) The laird and John are passing a hole in the moor, when the laird

turns his thumb over his shoulder, and says, "John, I saw a tod gang in

there!"

"Did

ye, indeed, laird?" cries John, all his hunting blood instantly on fire.

"Ride ye your lane to the toon; I'll hawk the craitur oot! "

So back

goes John for pick and spade, having first, of course, stopped the earth.

The laird rides his way, and all day he is foregathering with his cronies,

and "preeing the drappie" at the market-town–ploys in which his henchman

would ably and very willingly have seconded him. It is the hour of evening,

and the laird rides home. He comes to a mighty excavation on the hillside.

The trench is both long and deep. Very tired, and somewhat short-grained in

temper,

John is seated upon a mound

of earth, vast as the foundation of a fortress. "There's nae fox here,

laird!" says John, wiping the honest sweat of endeavour from his brow. The

laird is not put out. He is, indeed, exceedingly pleased with himself.

"'Deed, John," he says, "I wad hae been muckle surprised gin there had been

a fox in the hole. It's ten year since I saw the tod gang in there! "

Here the nationality of

the ironical humour consists in the non-committal attitude of the laird. It

is none of his business if John chooses to spend his day in digging a

fox-hole. It is, no doubt, a curious method of taking exercise when one

might be at a market ordinary. But still there is no use trying to account

for tastes, and the laird like a kindly man leaves John to the freedom of

his own will. History does not relate what were John's remarks when the

laird had fared homeward. And that, perhaps, is as well.

This, the Method Ironical,

with an additional spice of kindliness, is also Sir Walter's favourite mode

of humour. It is, for instance, the basis of Caleb Balderston, especially in

the famous scene in the house of Gibbie Girder, the man of tubs and

barrels:–

"Up got mother and

grandmother, and scoured away, jostling each other as they went, into some

remote corner of the tenement, where the young hero of the evening was

deposited. When Caleb saw the coast fairly clear, he took an invigorating

pinch of snuff to sharpen and confirm his resolution. 'Cauld be my cast,'

thought he, 'if either Bide-the-Bent or Girder taste that broche of wild

fowl this evening.' And then, addressing the eldest turnspit, a boy of

eleven years old, and putting a penny into his hand, he said, 'Here is twal

pennies, my man; carry tbat ower to Mistress Smatrash, and bid her fill my